Here’s a fact: some writers call themselves pantsers or discovery writers and can write an entire novel without knowing anything about what happens next. Others want to learn how to outline a novel.

Here’s a confession: I am an outliner.

For writers like me, the idea of not knowing anything about what happens in your book until you begin writing sounds paralyzing. You’re probably afraid that you’ll spend hours (if not years) writing scenes that don’t work, or worse, make you more confused about the story than before you started. I’d actually wager a lot of money that this is what brought you to Story Grid in the first place. Finally, someone is giving you tactical, practical writing and editing tools that you can apply to your own story without squashing your creativity.

I’m with you. This is what drew me to Story Grid.

And yet, even with all the brilliant tools Story Grid generously offers, it can be easy to burnout during the writing process if you’re not sure where you’re going with the Three Pillars of Storytelling: Plot, Character, and Setting.

Here’s a second confession: I’m an organized person for all my external responsibilities, but when it comes to my own writing, I need to train myself to reach my internal goals. This is probably why, for a long time when it came to my writing, I’d flounder in a mess of multiple ideas with little direction on what to do with them.

I don’t mention this struggle to limit the benefits of this post to my writing experience, but because I’ve talked to so many writers experiencing the same structural struggle that I could no longer ignore the question I was resisting: Should I use an outline to write my story?

Better yet: Can I use Story Grid to outline my story?

Better still, plan it?

While I acknowledge outlining is a specific approach to writing, taking the time to plan your story using Story Grid’s plethora of writing tools could diminish the emotional exhaustion you might experience without one.

Some writers don’t need an outline. I totally respect the discovery writing process. I also admire every writer who does enjoy an outline, or some form of story plan, and maintains enough mindfulness and patience to tackle their own.

If this is you, I’d love to share the 5 Steps to a Novel Outline that saved me, and I hope they liberate your creative mindset come time to write your manuscript. This is how to outline a novel.

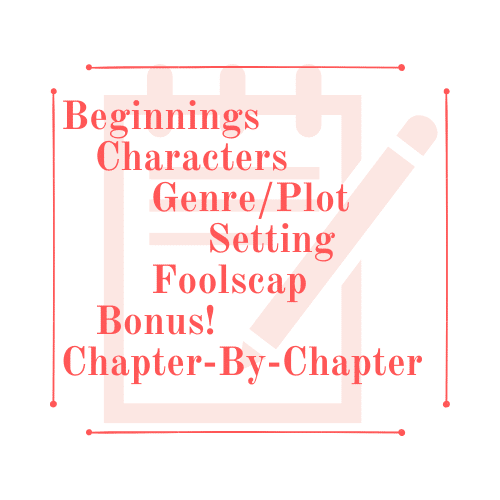

5 Steps: How to Outline a Novel

Story Plans can make writers who enjoy plotting more confident in their writing process. It can also keep their plot, characters, and setting on track while letting their creativity loose on the page.

With clarity on your final destination, you, too, can redirect your story in those extended Middle Build moments that feel overwhelming. All you have to do is turn back to your plan. Where are you getting lost or confused, and why? Is it your plot? Your characters? Your setting?

The beauty of the 5 Steps to outline a novel is that you don’t need to reinvent the wheel to develop a story that works. If you’re a Story Grid fan, and I’m assuming you are since you’re here (or are at least interested in learning more about Story Grid), you’ve probably already done most of the work. A huge thank you to Shawn and all the Story Grid editors hard at work, figuring out brilliant revelations about story structure and communicating them to us with succinct and applicable insights!

With these valuable resources, you can piece together that 500-piece puzzle itching inside your brain. Five steps are what you need to apply Story Grid methodologies to a plan that can organize and liberate your ideas.

Editor’s Note: For many of these five Steps, I’m going to recommend other posts already written by Story Grid Editors for a deeper understanding of story methodology. They are brilliant—if not story life-savers—and I seriously suggest you allot time to study and understand them. Although the five steps on how to outline a novel weave the recommended posts together in this post, your outline will greatly benefit from digesting the tools and strategies insightfully articulated in the links attached. I promise, they’re worth your while!

STEP 1: BEGINNINGS

Ideas can come to writers anywhere, but in order to live an author lifestyle, you can’t wait for inspiration to write that next novel. You won’t grow as a writer, either. How could you, if you’re not practicing your craft?

To avoid “writer’s block”—i.e. resistance convincing you it’s something else—start small. Storyteller Jay Shetty shares on a podcast interviewing Dr. Rangan Chatterjee how most people value lots of things with small priority, when it’s actually much better to value “small things with big priorities.”

To center your next story priorities, start with a few small things:

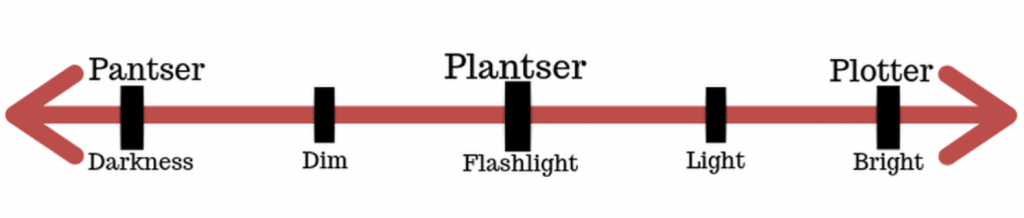

- An understanding of where you fall on the Outline Spectrum (are you more of a pantser/discovery writer, plantser, or plotter?)

- Write your story’s Logline

- Write your story’s Jacket Cover

OUTLINE SPECTRUM

The trick here is in understanding what level of an outliner/planner you are, and not judging yourself or comparing your style to other writers. Too often, writers experience burnout because they get discouraged when they compare their writing or story to someone else when, in actuality, only they can write their story.

Comparing your writing—or the way you write—to another writer will inevitably turn the outlining/writing process into a discouraging and exhausting waste of time. Being mindful of where you fall on the Outline Spectrum, however, frees you to plan your story as intensely or sparsely as you desire.

To do this, I encourage writers to evaluate where they fall on the OUTLINE SPECTRUM: a spectrum that can assess the type of writer you are (on a scale from pantser to plotter) and the value you, as the writer, cherish in that stage. Knowing where you fall on this spectrum is important to remember going forward; just because there are additional steps in the 5 Steps on how to outline a novel does not mean that you need to complete them all, or fully complete them, in order to draft a story that works.

In his book Self-Editing and Revision, James Scott Bell talks about how some writers, like pantsers, prefer to write a jacket cover and logline before drafting the manuscript. That’s it. In contrast, other writers who fall more on the plotting scale will not only complete all How to Outline a Novel steps, but will probably tackle the Bonus Step for an extra boost.

Please, when you look at this spectrum, view it with honesty. Lying to yourself will only squash your creativity, and the 5 Steps to a Story Plan is about liberating your creative energy and process, not shackling it.

The Outline Spectrum ranges on a scale of Panster to Plotter, and just like the value shifts driving a character’s ability to change according to Story Grid Genres, the life value on the Outline Spectrum directly relates to the type of planner the writer is, with Pantsers enjoying the dark (don’t tell me what comes next!) and Plotters wanting complete clarity (what comes next?!).

LOGLINE

A logline is a one sentence pitch of your entire story. When written and revised with intention, loglines also create clear, directive starting points for your story’s outline.

Here’s why.

A logline—or one-sentence (preferably 25-words) pitch that conveys the Hero, Goal, and Problem driving your story—is the perfect place to “test the waters” for your premise. One of the greatest resources to logline writing comes from Blake Snyder’s notable work on scriptwriting, Save the Cat!; however, the four logline requirements discussed in the book are not necessarily applicable for every storyteller.

What is advantageous for a writer is understanding the story’s protagonist, the protagonist’s want, and the extreme obstacles they will have to face in order to get that want.

What Save the Cat’s logline template overlooks are a story’s genre expectations. Reviewing how an understanding of Story Grid Genre global value shifts, controlling ideas, conventions, obligatory scenes, and sub-genres can change the game in how your logline hooks an audience.

Hint: Plot Structures that dodge genre expectations usually flop, so I like to recommend that writers don’t try to tamper with plot structures that work—i.e. Story Grid Genre expectations—and focus more on developing a unique character and setting to hook their audience. How is your character ironic for the situation? How is the setting different from any other setting in that same genre?

For more on loglines, check out Courtney Harrell’s Story Grid post here.

JACKET COVERS

Jacket covers, or the 250-300-word description you can read on the back of a book, is a description that elaborates your logline’s big ideas. You can practice writing your own jacket cover by finding ten books in your story’s genre (make sure they also fit the category, or age group, of your readership) and read the jacket cover. What are you noticing about these descriptions? One thing you should see is that they do not give away the ending, but most certainly suggest the high stakes that the protagonist must face in the Middle Build of the story.

To write your story’s jacket cover, consider how you could work off the Beginning Hook and Middle Build portions of the Beginning Hook, Middle Build, and Ending Payoff requirement in the Editor’s Six Core Questions. Do this without overthinking it. Take a break. Look back at your Beginning Hook and Middle Build descriptions. What stands out? What needs clarification? WHY does this stand out or need clarification?

Identifying the Beginning Hook and Middle Build of your story can help you revise your Jacket Cover with sophisticated insight, which will help you understand the big picture for your story and your story’s genre before writing the manuscript. (P.S. Make sure you don’t give away your entire Middle Build in your jacket cover, but allude to the high stakes and obstacles to come.)

For an example on how to write a Beginning Hook and Middle Build (that kicks butt!), listen to how Leslie Watts describes The Hunger Games in this podcast of the Editor’s Roundtable.

*****

Editor’s Note: For the next two steps, Characters and Plot, writers might want to work out of order. This is absolutely fine! While some writers think externally—they focus on plot more than character—others favor internal transformation and challenge—stories that are character-driven and emotionally advance the plot. Regardless of what YOU favor, both steps are essential and massively beneficial when developing outlines for your novel. If you’re feeling stuck on one step, skip to the next. Regardless, I recommend completing both if you favor the plotter end of the Outline Spectrum.

*****

STEP 2: CHARACTERS

Without an antagonist, there is no story. Antagonists are the true instigators of the plot; they are proactive and motivated to get what they want, which means, ultimately, they are the reason the story happens in the first place. There is no need for a protagonist without an antagonist.

Without a protagonist, readers and viewers have no reason to care about the story. We identify with a protagonist’s vulnerabilities and their struggles, with their competencies and determination to overcome their flaws.

Before writing, drafting up some Character Outline Worksheets—for at least your antagonist and protagonist—will save your story from spiraling into a messy and dull draft. Characters are your opportunity to make your story stand out, and the last thing you’ll want driving your story is a cast of flat, boring, and meaningless characters—i.e. characters who refuse to become or prove their meaningfulness.

To get a better understanding of WHY your characters do what they do, you need to understand their motivations. Exploring a character’s motivations is far more purposeful than drafting out physical traits that won’t have any impact on character development or advancing the plot. These seven factors will:

- External Want (What does your character want? This is directly related the external genre of your story. Learn about this in Shawn’s post here.)

- Internal Need (Even if you’re writing an External Global Genre, characters are going to connect with readers more if you give them an internal journey, too. This means that the Internal Need of your character—at least your protagonist—can directly relate to the life value shift driving their Internal Genre, which Kimberly Kessler teaches beautifully in this post.)

- Origin Story (Pay attention only to what’s significant to your current plot. Why do they have certain quirks or habits? How did emotional traumas influence these, along with other fears and flaws?)

- Harmful Idea (Essentially the opposite of your story’s Controlling Idea, which should directly relate to your Story Grid Genre. Controlling Ideas can also influence your story’s POV, which Leslie writes more about in this post. Once you’ve reviewed Leslie’s post, think about how your protagonist eventually learns the Controlling Idea and changes because of this life value shift, whereas your Antagonist does not. The Harmful Idea remains harmful for the Antagonist, but the Protagonist—capable of change—embraces the Controlling Idea. And note, Controlling Idea can be positive or negative, the Harmful Idea is just the opposite of whatever you choose for your story, and how your story ends.)

- Consequences and Stakes (What’s at stake for your antagonist and protagonist? How will life as they know it be impacted if they fail? Discovering your Story’s Core is helpful with these decisions, which Courtney Harrell and Parul Bavishi share more about here.)

- The Hook (What’s ironic about your character and their situation? Why is your character the worst or wrong choice to be dealing with the circumstances they are in? Why does this make them more interesting and how can you push this? What are your character’s motivations and why, something Savannah Gilbo highlights in her post on five questions to ask your characters.)

- Character’s Secret (What is your character hiding from everyone else and how can this negatively and/or positively impact their external and internal progress?

STEP 3: GENRE/PLOT

When I attended the Story Grid Live Conference in 2019, I had the pleasure of having dinner with Rachelle Ramirez, who emphasized how helping a writer select and understand their story’s GENRE is one of the most important things an editor can do. I whole-heartedly agree, especially since out of the three pillars of writing—Plot, Character, and Setting—plot is the one that is wired into our minds with subconscious recognitions of patterns in stories (according to genre).

In other words, genres set up specific expectations for readers, and failing to fulfill these expectations will likely end in a reader not enjoying your story. This doesn’t mean your story was necessarily “bad,” it means you wrote a story marketed for an audience who doesn’t usually like that type of story!

Story Grid gurus probably already have read Rachelle’s fabulous collection of Genre posts, which you can find in her Secrets to Story Grid Genres archive. If you haven’t read these already, I highly recommend you do. Read them after refreshing your memory on Shawn’s Genre 5-Leaf Clover.

Ultimately, a protagonist can be like nothing we’ve seen before, but it’s best to meet your genre expectations as they align with the protagonist’s CONTENT GENRE, or what Shawn calls your protagonist’s External/Conscious quest and/or Internal/Subconscious desire. Knowing your genre is key in how to outline a novel.

Find the global genre for both the External and Internal Genre driving your story, and then pick which one is your global genre. When you get to step five, you can decide how much you want to detail genre expectations into your story outline.

STEP 4: SETTING

Bestselling fantasy writer Bandon Sanderson offers an amazing writing lecture series on YouTube. In one of these videos he talks about Worldbuilding, and watching it just might change your outlining-of-setting-life.

Setting, like character, is one of the Three Pillars of Storytelling that can be funkified in order to make your story unique from every other story in that genre. Take epic fantasy (often Action/Worldview Genres). For a while in the eighties and nineties, this genre took an especially huge leap on a publisher’s favorite-to-buy-list. And then, unexpectedly, some series began to flop.

Why do you think some epic fantasy stories become huge bestsellers and others don’t?

Sometimes luck. Also because some writers failed to meet genre expectations—which confused their target readers. When writers try to do something structurally different instead of spice up the setting or drive the plot with unique characters, readers might finish the book disappointed.

Think about the Harry Potter series. Here you have Harry, an orphan-boy wizard, who follows a classic rise-to-riches tale that follows a Worldview-Maturation Internal Genre, paired with an External Action story that adds excitement and magic to the plot. We’ve seen these stories before. We love these stories, but what was exceptionally different about Harry Potter?

Hogwarts.

The wizarding world.

Harry. Hermione. Ron. Dumbledore. Snape. Professor McGonagall. Lupin. Fred and George. Sirius. THE CHARACTERS!

The magic world within our everyday world, and the belief that there could be a world like this in our reality, has been repeated in fantasy (or magical realism) stories. But Harry Potter’s cast and world itself is what made it so dang special.

STEP 5: FOOLSCAP

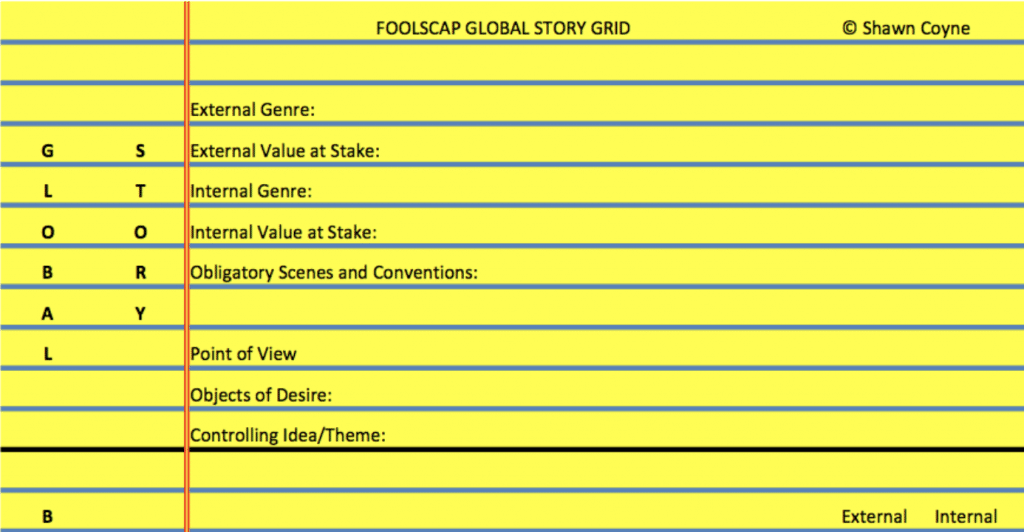

What Story Grid Editor Julia Blair calls “one sheet to rule them all,” and she couldn’t be more right!

By now, completing step five should be a piece of cake; all you have to do is take everything essential to a strong story outline and apply many of those important details into one page. This page will change your writing life.

It’s called the Foolscap.

Essentially, the Foolscap does an exceptional job at drafting your story’s 15 Spinal Scenes, which Shawn teaches intensively in his Level Up Your Craft workshops, and that he writes about with game-changing transparency here.

In a nutshell, the 15 Spinal scenes describe the 15 major scenes driving your global genre, each elevated by the same purpose that the Story Grid 5 Commandments use to structure a scene that entertains and works: Inciting Incident, Turning Point, Crisis, Climax, and Resolution.

Knowing these five scenes for your story’s Beginning Hook, Middle Build, and Ending Payoff will give you the checkpoints every writer needs in order to draft their story/character arch from page one to the end. And if you’re a serious plotter, I’d challenge you to take Step 5 one stretch further and plot the 15 Spinal scenes for your Internal and External Genre, not the Global Genre driving your Foolscap alone.

Editor’s Note: In the Bonus step for How to Outline a Novel, you will weave these 15-15 scenes (for your Internal and External Genre) to ensure your characters don’t fall flat. However, only one of these genre choices will work as your Global Genre.

BONUS STEP: CHAPTER-BY-CHAPTER ANALYSIS

Feeling extra plotty and brave? Plan a chapter-by-chapter breakdown of your story. Use the 5 Commandments to mentor each scene, but don’t be afraid of switching up certain elements as you write. When you’re ready, weave your 15-15 Internal and External Spinal Scenes in a way that supports one another and escalates the stakes.

HOW TO OUTLINE A NOVEL: BIG TAKEAWAY

So, how to outline a novel?

For some writers, usually those who favor plotting, story outlines can provide the clarity needed to give him/her the confidence to finish their story. Cultivating mindfulness as you develop your planning process can bring awareness to when your outlineg stifles or liberates your creative spirit, and you should pay attention to it without comparing yourself to other writers.

That being said, if you are a writer who enjoys plotting at any level, using these 5 Steps on how to outline a novel just might be the organizational tool you need to hold yourself accountable to your writing intentions, while also boosting your confidence as you finish the first draft!

Like I mentioned in the beginning of this post, you don’t need to reinvent the wheel to develop a knockout outline for your novel. Take advantage of the brilliant insights shared in the many Story Grid posts and podcasts. Start with the links supporting the 5 Steps on how to outline a novel. Then, take a deep breath.

I’m rooting for you!

Hey Writer! If you want to learn more about writing outlines for novels, I’d love to share my insights with you. By signing up for my email list, you’ll get free downloads for my Story Outline Character Templates and Worldbuilding Template. Visit my website to learn more, or don’t hesitate to email me with questions.

Happy Story Gridding!