Featuring Hamilton‘s Aaron Burr

Outlining the protagonist is a popular way to start building a story, but unless a hero has a mesmerizing antagonist challenging them to become a hero, the story will flop.

Don’t feel bad if you’re focusing on your main character first. I’ve been doing the same thing for a decade: building a cast of characters by creating the backstory of my protagonist and filling in the supporting cast—including the antagonist—around the protagonist’s wants, needs, and missions later.

Every time I did this, when it came to putting the plot to paper, I’d run into the same something-isn’t-exciting-about-this-story-anymore roadblock. The reason? My supporting cast felt humdrum—sometimes painfully flat—especially when placed beside the riveting main character that I’d spent so much time inventing.

Plot is important, but it’s unlikely readers will connect with any story that lacks a variety of compelling characters. This is something Lin-Manuel Miranda skillfully avoided in his theatrical masterpiece, Hamilton, the Broadway phenomenon that electrifies the stage with a complex mix of primary and supporting characters.

Inspired by Lin-Manuel’s genius, I’ve decided to dedicate my next handful of Story Grid blog contributions to teaching writers how to create a cast of knockout characters by understanding and modeling how Hamilton did everything right.

For today’s introduction, we’re not studying Alexander Hamilton, the protagonist, but Aaron Burr, the antagonist. Why? Because a cast that lacks a complex antagonist is robbed of an essential and riveting external force necessary to inspire a main character’s motivations and desire to change.

While external forces other than Burr certainly exist in the musical, Hamilton’s rebellious fighting and writing actions, the shadow of Hamilton—what he can’t understand and what he would desperately fear to ever be—is encapsulated in the sympathetic, sophisticated, complex, and eventually spiteful leading antagonist, Aaron Burr (sir).

Bottom line? Burr behaves in a way Hamilton refuses to follow: someone who stalls by patiently waiting for his moment instead of assertively defending what he believes through action, despite the consequences.

“If you stand for nothing Burr, what will you fall for?” – Alexander Hamilton

A knockout story needs a complex antagonist who leaps off the page—or stage—or screen—to create a story that will linger in a reader’s heart and mind.

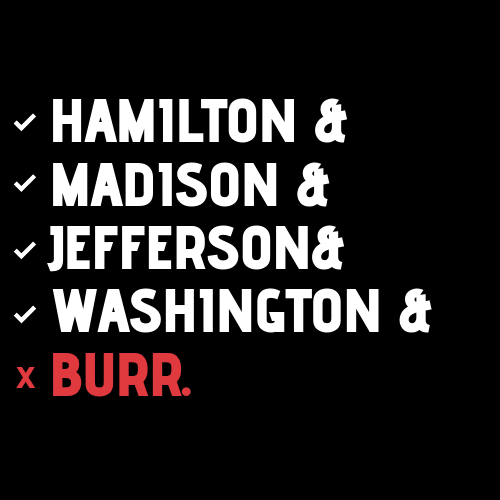

Of course, there are many antagonistic characters in Hamilton. King George III and his British battalion, Thomas Jefferson, and James Reynolds notably provide conflict and hostility that Hamilton must act against, but without Burr, Hamilton’s foil, constantly looming in the room where it doesn’t happen, the story lacks that knockout and necessary flare.

A Hero is Only as Interesting as the Antagonist

It’s no accident that Leslie Odom Jr., who originally played Aaron Burr in Hamilton, won the Tony for leading actor in a musical. In any story, the main character is only as interesting as the antagonist (or villain) they’re up against.

Think about it: there is no need for a hero to become a hero unless there is a villain calling them to act. In some cases, the villain is more powerful than the hero. Other times (like Hamilton), a difference in how the protagonist and antagonist respond to external forces–diametrically opposed, foes–is what stimulates the tension between the two.

The power divide is what makes the main character’s journey interesting, exciting, memorable, and heart wrenching. Without the challenge of overcoming that divide, why else would we hang on to watch the main character fall or rise in the Ending Payoff?

Why root for someone who doesn’t tackle anyone or do anything worth rooting against?

This is why it is essential to start any writing project by developing your antagonist. First.

For example, consider Alfred Hitchcock’s famous insight, “drama is life with the dull bits cut out of it.” This holds true when creating a story’s characters, who inevitably drive the plot.

Yet how can we as writers expect to cut out the “dull parts” if there isn’t a shadow-like antagonist providing page-turning moments along the way?

We can’t.

Without a killer antagonist, there is no raw, authentic, and external figure motivating, if not forcing, a main character(s) to act.

It’s true that our love for the hero is a major reason we hang on to a story. We all adore a character worth rooting for—a model of honor, grit, and unquestionable magnetism. And yet, the hero only becomes the person they are born to be if challenged by a memorable antagonist:

- Simba decides to “remember” who he is and save his homeland by confronting Scar.

- Harry Potter willingly walks into the forest to sacrifice himself in order to destroy Voldemort.

- Katniss becomes a hero by protecting Prim from the madness of the Hunger Games orchestrated by President Snow.

Fully realized antagonists—great characters that emulate parts of the main character’s self (and ourselves)—stand the test of time.

- Scar resembles a king who puts his own desires and needs above his pride and homeland, something Simba needs to set aside before he takes his rightful place on Pride Rock.

- Voldemort chose Harry because of how alike they are, but Harry’s choices are what separate the sacrifices each character makes–and therefore insurmountably impacts what is gained and for whom.

- Snow constantly respects Katniss’s boldness and intelligence, even insisting that they don’t lie to one another. But where Snow uses his power and influence over people to manipulate and control them, Katniss learns to wield her heightened status as a means to rallying a people–and then stepping aside when the time comes.

- And Burr…let’s take a look at him now.

THE GREATEST VILLAINS OF ALL TIME…AND BURR.

If a string of villainous names haven’t already filled your thoughts, this list of some of my favorite non-stop antagonists might trigger some emotions: Voldemort, Maleficent, Darth Vader, Nurse Ratched, Thanos, The Wicked Witch of the West, Hannibal Lector, Mystique, Sauron, Annie Wilkes, Auric Goldfinger, and…

Burr.

If you haven’t seen the performance or listened to the Hamilton soundtrack yet, you should. It’s a “work of genius”; I couldn’t have written a better cast of characters “if I tried…and I’ve tried.” (Wink, wink to my fellow Hamilton fans.)

But what makes Hamilton sensational? The story, music, dancing, of course. But mainly the complex characters, including Burr.

Especially Burr.

It’s not an accident that the first person we see on stage after the curtains rise is Aaron Burr, which leads us to a question some analysts have asked: Is Aaron Burr the Protagonist?

Although I stand strong on the Hamilton-is-the-protagonist side of the debate, I do believe that part of the reason Hamilton’s cast of characters is so impenetrable is because of each player’s undeniable imperfections—there are no saints in this story. In fact, Miranda develops Alexander Hamilton both as protagonist and major antagonist. Think about that.

Making Hamilton and Burr equally complex, Miranda paves the way for us to like the story’s notorious narrator and villain–if not love him. By doing so, Lin-Manuel (and Ron Chernow, whose book was the inspiration for the story) unlocks a truth sometimes forgotten in history classrooms: Our founding fathers were brilliant—and often arrogant jerks.

Before the Hamilton phenomenon, most Americans remembered Aaron Burr not as a prodigy father to his daughter and arguably one of America’s first major feminists, but Hamilton’s murderer.

The complexity of Aaron Burr in Hamilton, however, reminds us that he was much more than “the villain in” Alexander Hamilton’s “history.”

Much more than the infamous Vice President who killed his friend in a duel.

That’s right, they were friends!

HAMILTON AND BURR, MORE SIMILAR THAN NOT

In Lin-Manuel Miranda’s version of history, Burr reigns as the constant foil in Hamilton’s fight for his reputation. Burr’s 655 lines in the play are second only to Hamilton’s 916. What’s even more amazing is that through all their conversations, encounters, and disagreements, Hamilton and Burr remain friends. Good friends. Confidantes. Even allies.

Hamilton shows how an ally can become a story’s master villain.

To understand how Lin-Manuel accomplishes this, it’s important to look at the main difference separating the two characters’ behaviors.

Burr waits. Hamilton acts.

THE ADVANTAGE OF MAKING YOUR ANTAGONIST SYMPATHETIC

Hamilton and Burr are more alike than not; they’re both orphans and lawyers, smart-as-heck, believe in the revolution, and adore their children…the list goes on. But Alexander Hamilton feverishly acts (“I am not going to throw away my shot”) while Burr nervously waits (“I have everything to lose”).

Burr’s insistence on waiting perhaps presents the most important motif in the theatrical version of the story.

Note

A motif in a story is a distinctive feature or definitive idea that is repeated throughout the story to emphasize its importance.

Illustrated most clearly in Aaron Burr’s solo “Wait for It,” the audience gets an inside look at how Aaron Burr’s brain works: His parents are dead, he has a legacy to protect, his grandfather was a “fire and brimstone preacher,” he is in love (with a woman married to a British officer!). In other words, he resolutely believes he has everything to lose.

Understanding the inner motivations, values, and beliefs of Burr—whom history paints as the “bad guy”—makes him sympathetic. Through this song the audience, for the first time, actually understands why Burr is holding back.

This motif is pushed further later in Hamilton, after the Revolutionary War, when Hamilton pleas with Burr to help him write a collection of anonymous essays (The Federalist Papers) to defend the U.S. Constitution.

Despite being Hamilton’s friend, Burr refuses to assist–a decision that angers Hamilton: “For once in your life, take a | Stand with pride. | I don’t understand how you | Stand to the side.”

To the audience, Burr explains that he keeps his plans “close to his chest” while the other supporting cast members chant “wait for it” in the background.

Burr’s actions and reactions as a foil, as well as the “wait for it” motif repeated throughout, remind us why Burr is holding back. This doesn’t make us less frustrated with Burr’s hesitancy but it does make us understand where he is coming from, and it elicits our sympathy by reinforcing why Burr waits.

This choice, brilliantly pushed by Lin-Manuel, pulls our sympathy trigger with flawless effort. He has turned Burr into a character capable of outlasting time: Burr is no longer only remembered as the guy-who-shot-Hamilton.

Lin-Manuel has made Burr real by establishing him as sympathetic.

OUTLINING THE ANTAGONIST’S STAKES AND CONSEQUENCES

To understand what motivates a character to do something, a writer needs to know what is at stake for that character, hence, should they act or not act.

By starting with your antagonist, you can fine-tune their motivations and use them to constantly remind yourself of how these oppose the intentions, goals, wants, desires, and actions of your main character.

Protagonist and antagonist should be intricately (and constantly) linked. Whatever one does should directly impair the goals, wants, and desires of the other.

A trick to making sure you’re doing this well is by outlining a character bio for your antagonist before your protagonist and other supporting cast. As you do this, stop to ask, “How does my antagonist’s beliefs, values, and actions directly impair my protagonist?” When you start writing your Foolscap (and/or other important scenes involving the antagonist), question how your antagonist is in conflict with your protagonist. If they’re not, step back and figure out how to tighten the tension between the two. Not only will these clarifications make your protagonist easier to develop, it will make them 100 times more interesting.

Ultimately, by answering your list of antagonist bio questions, you’ll weave a story deeply rooted in the protagonist vs. antagonist battles that escalate as you approach the Ending Payoff’s anticipated final showdown.

How this ties back to stakes…

Both protagonist and antagonist should have a lot to lose. By directly opposing the stakes of the foes, a writer escalates the consequences that will inevitably happen when one character loses—and one of them must lose.

The question of how consequences will impact the protagonist and antagonist is why readers hang on extra tight, and the more you encourage us to love (or at least sympathize with) the antagonist, the more exciting all the events building towards that final, cataclysmic–wait for it–moment.

To sum up:

- Establish clear motivations, wants, and desires for your antagonist.

- Do this in a way that establishes sympathy in the reader or audience.

- Tighten conflict between the protagonist and antagonist to raise the stakes and consequences for each.

If you do this, your plot will be all the more thrilling because the “parts” (as Hitchcock called them) are driven by complex characters and divergent conflicts.

MY FRIEND HAMILTON, WHO I SHOT

– Aaron Burr

In an interview with Stephen Colbert, Lin-Manuel Miranda noted how later in his life Aaron Burr would walk around saying, “my friend Alexander Hamilton, who I shot.”

The difference in how these two men became immortalized in history is best explained by their contrasting motivations.

What motivates Burr (and holds him back) starts to change direction later in the story, and since we know from the very first scene that Burr is the “damn fool who shot him (Hamilton),” we also know that something will eventually make him crack.

Remembering this, we in the audience start to think less like Hamilton (who asks, “What are you waiting for?”) and wonder more about what external force will finally push Burr to the duel. We think, “How long can he wait?”

Not knowing the answer—but knowing Burr’s motivations, characteristics, and emotions worthy of our sympathy—we keep our unfailing interest in his progression.

We’ll wait for more.

MAKING YOUR ANTAGONIST SYMPATHETIC

Help readers/viewers understand your characters’ actions and motivations throughout through their external and internal reflections, revelations, actions, and events.

Try answering these questions when writing your antagonist’s bio:

- What’s the backstory? Was there a tragic origin story? If so, definitely make a note to show this at some point, but not in a way that overwhelms the reader.

- How do they demonstrate style, intelligence, strength, or competency? Voldemort doesn’t act for reasons that make us like him, but boy-oh-boy does he have style and competence. Sometimes, evil antagonists can inspire admiration when they show great style or competence.

- Can I build tension by making them a friend or lover, or have some other kind of relationship? You know, to complicate matters even more.

- Does my antagonist avoid caricatures—i.e. what makes them imperfect? Give them something they care about or love. What will they fall for?

- How do I make them vulnerable? Establish what their weakness is and milk this in a way that builds tension while avoiding clichés. What does the protagonist hold against them? For instance, Burr waits while Hamilton acts, which makes it even more ironic than in the final duel, Burr is the one who acts–killing Hamilton–in the one moment Hamilton finally waits.

- What are the stakes and consequences for my antagonist if my protagonist wins? Make these clear, directly opposed to your protagonist, and disastrously high.

- How are my antagonist’s actions directly in conflict with my protagonist? Every time your antagonist does something that impacts the major events of the story, how does this conflict with your protagonist’s goals/wants/relationships/etc.?

MORAL OF THE STORY…

A bad guy who is pure evil is at high risk of being painfully cliché and boring.

You’ll recognize that Burr not only transcends any hints of dullness in Lin-Manuel Miranda’s Hamilton, but also has become one of the most beloved and respected characters on Broadway. Much of this is thanks to his complex and sympathetic actions and traits that foil Hamilton.

Not to mention Leslie Odom Jr. has the voice of an angel.

Need help starting your character list? Visit www.abigailkperry.com and sign up for my Slush Pile Survivor email list. Currently my subscribers and I are walking through the cast of Hamilton via my Character Craze video series. We’d love for you to join us!

“I have the honor of being your obedient servant.” – A. Per