I’m a writer, and of all the methods and approaches I’ve studied about the craft, Story Grid is the one that makes the most sense to me because of its simplicity and scalability. I’m also a Story Grid Editor, because I believe that good writers are made, not born. I’d like to show you one of the ways that I’ve put Story Grid to work for me as a writer, and why I think it’s one of the best tools out there. I’ll also share a Scrivener template that I’ve customized based on the Foolscap.

The deep down, nitty gritty, true value of the Story Grid method is as a diagnostic tool. Its real power lies in applying it over and over to masterworks, to assimilate the structure until it comes unbidden when you write. Fellow Story Grid Editor Rebecca Monterusso urges us to find and study masterworks. That’s the most immediate way that Story Grid will help you be a better writer. Find the masterworks in your genre. Revisit your personal favorites and apply the principles of the Story Grid method to analyze their global stories using the Foolscap, to dissect their scenes with the razor-sharp concepts of the 5Cs, and hold their pulsing turning points in your bare hands.

But let’s put our editing mind aside and put on our favorite funky writer’s hat because I’d like to show how I use the Foolscap as a tool to help draft my stories.

The Story Grid Foolscap has its origin in a conversation between at-that-time-aspiring writer Steven Pressfield, and documentary filmmaker Norman Stahl, who told Steven that he should be able to distill the essence of a story, any story, into three parts (beginning, middle, end) that could be written on a single sheet of legal-sized paper.

These days, Pressfield claims, he never begins a novel until he’s worked up its Foolscap.

Later, Shawn Coyne drew similarities with his own structured approach to manuscript analysis and incorporated the Six Core Questions and the Five Commandments of storytelling, resulting in the Story Grid Foolscap.

I believe it is one of the first and best writing tools an author should reach for when starting a new manuscript.

ONE SHEET TO RULE THEM ALL

The concept of using a single sheet of paper to plot a course of action is not unique to the Foolscap. In the writing world, distilling a storyline down to its essence is a common practice. A story spine is essentially similar. The notion of a story spine appears in Brian MacDonald’s Invisible Ink, although MacDonald later claimed not to be the originator of the story spine’s language.

A set of guidelines known as Pixar’s 22 Rules of Storytelling first appeared in a series of Twitter posts by Emma Coats, a former Pixar writer. It was later compiled and can still be found on the internet in various forms. Rule #4 describes the structure of a story spine as a series of beats that lead the reader through the action, smoothly and logically.

Once upon at time there was _____. Every day, _____. One day _____. Because of that, ____. Until finally _____.

The business world also makes use of the single sheet format. Lean is a management approach to maximize output and minimize waste that has gained traction far beyond the manufacturing floor where it began. It employs a series of tools intended to standardize business practices, one of which is known as the One-Pager.

The Lean One-Pager distills all the relevant information related to a project, problem or concept onto a single sheet of paper. It forces clear thinking and focuses attention on the critical mission. It’s a communication and organization tool that can be applied widely. It clarifies a complicated issue.

The creation of a One-Pager requires the creator to begin with the end in mind, list key points, and identify the message.

Sounds a lot like a Foolscap to me.

What all of these methods or concepts have in common, is that they are exercises meant to be undertaken BEFORE the completion of a product.

So the Foolscap is—in case you need any more convincing—an excellent writing tool that can be used to inspire creation and set a course of work.

A WRITER’S TOOLBOX: HOW I USE THE FOOLSCAP

Like a lot of you, I’m already prepping for Nanowrimo, and I’m using the Foolscap to lay the groundwork for that upcoming writing blitz, developing and testing story ideas.

I’ve created a blank Foolscap that you can download as a Google Sheet to either edit online or print and fill out by hand. You’ll see some small modifications to Shawn’s version, inspired by my own writing and editing experience and that of other Story Grid editors.

Along with a blank Foolscap, I use notecards and a Scrivener template of my own design as I develop a story. I’ll walk you through my process, but never forget that this is merely Form, and not a Formula. One size does not fit all, and your results will vary.

I’m going to start by telling you something you already know.

You can find details on scenes and conventions, theme and controlling idea in the online Story Grid resources. The Fundamental Fridays blog series is a rich and robust source of specific details collected and curated by the Story Grid Editors. If you’re like me, you’ve printed ‘em all and have them easily at hand.

IT’S ALL ABOUT VALUE

Now that you’ve picked a genre, you have an associated global value. More importantly, you have a global value progression, and you’ll need that as you work through your plan.

If you are unsure about what the global value progression is or why it’s important, I highly recommend that you go back and reread Valerie Francis’s Value Shift 101 article.

Simply put, when you commit to a genre, you know what values your story will turn on.

We’re going to apply the global value progression to the Foolscap and determine what transitional scenes you’ll need to write as you progress from Beginning Hook to Middle Build, and Middle Build to Ending Payoff.

As you move from your setup to the meat of your story (Beginning Hook to Middle Build), you need a scene at the end of the Beginning Hook to shift the internal and external genre values in a Big Way.

As you enter the Ending Payoff, you must have a scene at the end of Middle Build to shift Internal and External genres in an Even Bigger Way.

For example, a Worldview/Maturity story may move the Protagonist from Naivety Masked As Sophistication at the start of the Beginning Hook to Naivety or Ignorance at the transition to Middle Build. By the end of the Middle Build, the Protagonist moves beyond Ignorance and gains Understanding that will lead them to Wisdom in the Ending Payoff.

The value continues to move throughout each act as the Protagonist struggles to make progress on their goal (their object of desire). The transition at the end of the Middle Build reflects a different step in the process, not necessarily the direct next step from the value shift at the end of the first major transition.

Write down the major transitions that you have determined on your Foolscap. Remember, you can change them later. Your commitment to genre is fuel for the engine that will get you through the story. The important thing is that the first one is a significant change, and the second one is even bigger.

THE PARTS OF THE BEAST

Most writers start with some sort of a premise, a “what if” idea. What if a human boy was raised by the ghosts of the dead? What if a mild home-loving folk were thrust into the greatest conflict of their world? What if a rule-breaking loner became the face of a revolution? Some writers may have a character concept they want to put through their paces; others start with a world in mind where aspects of nature or magic or society are forces to be reckoned with.

This is your Beginning Hook, and your global Inciting Incident has its roots here.

Now I’ll ask you to skip past the Middle Build for now to the Big Climax scene. The Ending Payoff is intimately linked to the Beginning Hook, and here is where you’ll eventually come full circle, fulfilling the hopes raised in the BH, answering questions, echoing and emphasizing theme.

J.K. Rowling gave us her best writing advice in the Harry Potter series: “I open at the close.” Rowling embedded layers of meaning in this enigmatic statement. Not only does it harken back to her Beginning Hook, it’s meta-advice to the writer. Start with the end in mind.

Now you know, more or less, your start and your end points.

Remember the Pixar story spine? We can see how that fits into the three act Story Grid structure:

- Beginning Hook: Once upon a time there was ___. Every day, ___.

- Middle Build: One day ___. Because of that, ___. Because of that, ___.

- Ending Payoff: Until finally ___.

There’s a great little video by South Park writers Matt Stone and Trey Parker that I recommend you watch. It’s just over two minutes long, and will help you as you work up a story spine. Basically, you never want the beats of your story spine to connect with “and then…” Make it dynamic.

With your story spine sketched out, go back and think about each act, knowing that your major scenes need to move the value or charge in the direction you’ve already determined.

SCENEWORK

At this point I fall back on a technique I learned from Robert McKee’s Story. Write your scenes in one or two simple sentences onto one side of an index card. Don’t kill yourself over whether or not it’s a true scene yet. These can be impressions, movements, or sketches. You can jot down a note like, “Something happens here to change the Protag’s mind about who the Enemy really is.” At this point, it’s entirely all right to leave blanks or be vague. If it doesn’t come easily, don’t worry. It will come later as you’re immersed in the writing process. It’s amazing how your brain deep-thinks these things during the act of writing.

I’m also a huge believer in placeholders. I tend to use the word Elephant whenever I can’t think of a name: Mr. Elephant, the Elephant River, Elephant & Sons Storage. I go back when the first draft is done and search the placeholder term, making a list of things that need names. Obviously, if you’re writing about zoos, circuses or safaris, you’ll want to choose a different word. Pressfield makes use of the editing phrase “TK,” meaning “to come.”

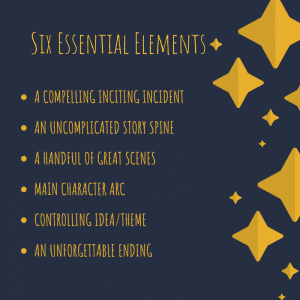

Director and screenwriter Paul Schraeder recommends developing your story material so that it includes these six essential elements:

Work the cards. Move them around. Lay them out. Group them together. Think about what’s missing. Remove the cards that don’t lead you through from your beginning hook to ending payoff in a chain reaction of events.

Scrivener has a notecard view that will let you do that within the program. I like to go with the physical cards to start, because if I’ve got a whole bunch of them, between global story, subplots, and character arcs, I can arrange them on a tabletop or the floor and see the story as a whole. My dinky little laptop screen isn’t big enough to show me everything at once.

Going back to the Foolscap, you see that within each act are the Five Commandments, making for a total of Fifteen Core Scenes that create a scaffolding or structure for a potentially workable plot. I always have several cards stacked under the Progressive Complications, and list them as bullet points within the Progressive Complications when drafting out the Foolscap. The Turning Point Progressive Complication is critical, and I’ve borrowed from Valerie to set it apart in my version of the Foolscap.

By now, you’ve got a strong story spine, a sequence of impactful scenes and a pretty good feel for their placement in the Foolscap based on the transition point values of the global value progression you selected earlier.

YOU KNEW THIS WAS COMING

That’s the easy part. Now you must write.

You don’t have to write your scenes in order. Some people prefer to write straight through from “Once upon a time,” to “happily ever after, and wiser as well.” I don’t write sequentially, but it’s entirely a personal choice. I write where my passion or emotions draw me, the heartfelt scenes.

Steven Pressfield writes out of order, and he (of course) advises the writer to tackle the toughest scenes first. He’s such a manly writer; Ernest Hemingway would be proud. Pressfield’s fiction has taught me more about men than my own father. And a heck of a lot about writing to boot.

But write where you’re drawn. In this creative phase, you need to capitalize on your excitement for the story. Court the muse. Give her what she wants. Later, as you’re editing, it’s not unusual to find that some of your best work comes from that place.

If you get stuck, go back to the Foolscap you created. It’s a road map, a blue print, a plan. You can adjust and modify it as needed. Maybe you find a scene works better before the Middle Build Turning Point rather than after it. Or you realize you’re writing a love story after all. It’s a lot easier to change your Foolscap than realize it after the fact and have to deal with major rewrites.

Let’s be honest, for some of us, Shawn Coyne’s article The Math was like the pusher’s first sweet treat. This Many Scenes + This Many Words Per Scene = A Novel! But when we climb out of the gutter of self-delusion, we see that Story Grid is not a magic formula. It’s a Course of Work.

Don’t think about writing a whole novel. You can write a 2000-word Progressive Complication or Crisis scene. Break the story into manageable pieces. It’s why the Pomodoro Method works. You can do Whatever, for 25 minutes. I suspect that even Stephen King takes more than 25 minutes to write a scene, but if you keep at it, you’ll get it done.

YOU DON’T HAVE FOREVER TO WRITE THAT NOVEL

Foolscapping streamlines the 10,000 hours said to be needed to master your craft. Shawn believes it is “an exponential reducer of labor.”

For Nano, we don’t have 10,000 hours. Even if we wrote for 8 hours a day for 30 days, after regaining consciousness in mid-December, we’d find that’s still only 240 hours, or 2.4%. Just so you have a feel now for how long that 10,000 hours is.

The Foolscap should be the first tool you reach for when you’re writing fiction from scratch. According to Pressfield, it’s “a way to kick your ass … at the very start of a project.” Or to guide you when you’re lost and don’t remember all those awesome ideas you had when you started.

Use the Foolscap to set your targets and go after them.

_____________________

I am deeply grateful to Shelley Sperry and Sophie Thomas for their thoughtful insights and keen eyes on an early draft of this article.