In the epilogue of The Story Grid, Shawn Coyne says:

“The problem that bedevils most novice writers (and even some seasoned pros) is that they fall in love with the glamorous aspects of the literary trade–the romance of “the creative process,” the thrill of dashing off chapter after chapter in a white heat of inspiration, etc.–and they undervalue the blue-collar aspects of Story construction and inspection–understanding and mastering Genre, Story form, character, Story cast, and so forth. They fail to learn how to edit.”

This blue-collar process doesn’t begin merely after the first draft–it begins at an idea’s inception.

Hard Truth: Not Every Book Idea is Worth Writing

Writing a story is an all-consuming process. It devours time, energy, brain power, and not least often self-esteem (can I get an amen?)—but it’s all worth it to tell a story that moves you and connects with your audience.

In order to reach this coveted end, your concept must contain enough raw material to cut into a finished gem. The truth is, the price is too high to pursue story concepts that are less than worthy. Figuring out the difference between a concept better left as a thought experiment and one worth writing? This is a trademark of turning pro.

But how? How do we objectively determine if our book idea is the diamond in the rough—or just rough? Is it possible to make this determination without a first draft?

My blue-collar bones cry, “Absolutely, yes!”

Primary Vetting Tool

Story ideas spark in an infinite number of ways. It can be an image, a line of dialogue, an abstract question…you name it. But whatever it is, that seed of the story must be expanded into a sizable amount of raw workable material. This raw material—the story concept—is what we are vetting.

And what is our frontline tool for determining if our book idea has chops?

The Six Core Questions Analysis.

At its essence, the Six Core Questions Analysis is an abbreviated Foolscap Global Story Grid, and also one of the key diagnostic tools Certified Story Grid Editors use it to evaluate a draft.

But even in the pre-draft vetting stage, the Six Core Questions provide well-rounded breadth and depth of the story concept–enough to make our prognosis and still leave plenty to be developed and imagined later.

Answering the Six Core Questions is the Minimal Viable Product of a Story.

Question 1: What is the Global Genre?

Looking at Genre through Story Grid eyes is a distinct experience. It’s not the categories you see on bookstore shelves, it’s a set of specific information readers want to know before they partake. Shawn defines these through Genre’s Five Leaf Clover.

Here in Question 1, we’re talking about the content leaf. Shawn lists 12 major content genres, which are divided into two main silos: external and internal. Some stories portray only one genre, but the richest stories will have both.

The key to a story that works (and in our case, a concept with merit) is one of our genres, either internal or external, has to play head-of-household. This, then, becomes the global genre. There is no wrong answer, unless you don’t actively choose one.

Remember, you can make changes later if you need to, but making this decision will make all future decisions immeasurably easier.

Question 2: What are the Obligatory Scenes & Conventions?

In other words, what are the audience expectations for your chosen global genre?

If it’s Action, we’ll expect the hero/victim/villain triad. If Thriller, we’re waiting for the moment the hero becomes the victim. In Horror, we know the victim is the victim and the monster is the monster from the get-go. And so on a so forth for each genre.

So, how do you figure out what your genre’s obligatory scenes and conventions are? Great question!

First, by reading (ahem–and watching movies) in your selected genre, then by paying attention to what strikes you. What are the big moments of the story? What scenes make you sit up in your seat, or hide your face, or cry cry cry? These are the scenes that invoke the primary emotion of the genre, and they are what the reader is wanting when they pick up your book in the first place.

In Pride & Prejudice: The Story Grid Edition, Shawn says:

“The reasons why stories don’t “feel right” when they do not abide the genre’s conventions is that they are the key ingredients that combine to deliver the core emotion of a particular genre. Without clues and red herrings, there will be no sense of intrigue in a mystery story. Likewise, without the ten conventions inherent in Love Stories, the reader will not be spellbound by romantic feelings for the protagonist/s.”

Obligatory scenes and conventions aren’t cliche–they are the foundation for the reader’s experience.

Question 3. What is the POV/Narrative Device?

Who is going to tell the story? How are they going to tell it? This is a crucial decision, one that can completely transform the tone and meaning of a story. Your choice of narrator should never be arbitrary. It should get as much thought as your genre and be an intentional choice.

- Single or multiple POVs

- 1st or 3rd person

- Use of Free Indirect Style or not

- Past or present tense

- Any other narrative device: letters, unreliable narrator, telling a story to children, framing the story by opening with ending and cutting back to the beginning, etc.

Question 4. What are the Objects of Desire (Wants/Needs)?

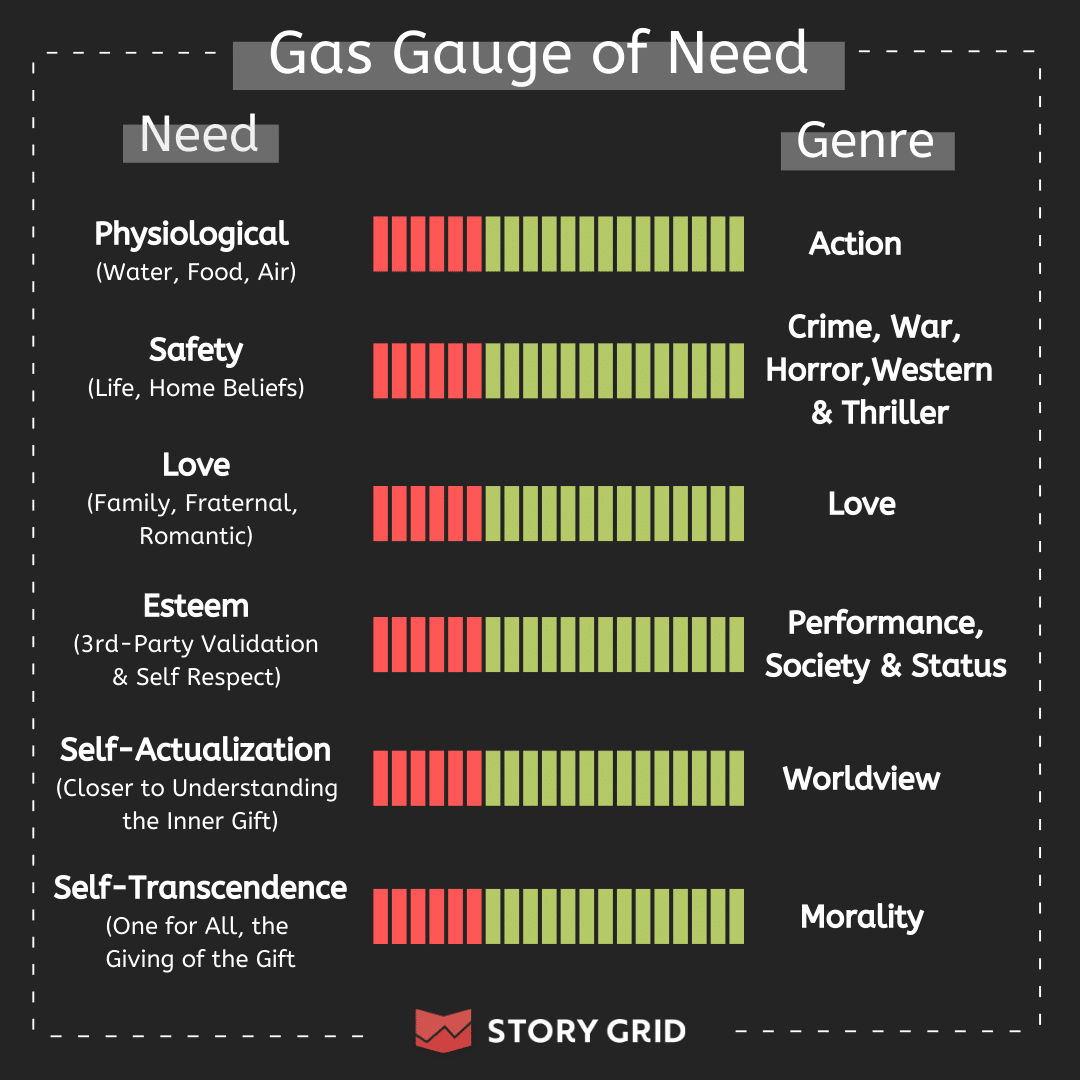

Answering this question gets to the core of our character and the story you’re trying to tell. The external genre drives the character’s WANT, their conscious object of desire. The internal genre drives the character’s NEED, their unconscious object of desire.

Honing in on your character’s WANTS and NEEDS will drive everything they do in the story. It’s the motivation behind his or her actions/choices. Focus your characterization efforts here, in wants/needs, rather than on random lists of character traits/preferences.

Remember, character is defined by action. Clear WANTS & NEEDS articulate which actions your character will take.

Question 5. What is the Controlling Idea/Theme?

Now, at this early stage, this one may be difficult for you to nail down–partly due to that so much is discovered about a story as it’s written, but also because we all make the Controlling Idea/Theme much more complicated than it is.

The Controlling Idea/Theme is one sentence that sums up the argument your story poses and sets out to prove through its narrative.

Many writers claim they aren’t trying to prove any sort of universal truth, they just want to tell an entertaining story, and that’s fine. But their readers are going to find one anyway because humanity is hardwired to see meaning.

That said, it still doesn’t have to be complicated. The Story Grid provides a simple frame for capturing your Controlling Idea/Theme:

[Global Value at Stake] is [won/lost] when [specific circumstances of your story happen, often related to the internal genre].

- Justice prevails when the protagonist engages her inner darkness as passionately as she does her “positive” side. (Silence of the Lambs)

- Love triumphs when we dispel base attitudes and embrace the vibrant mix of humanity among all social classes. (Pride & Prejudice)

Question 6. What is the Beginning Hook, Middle Build, and Ending Payoff?

Can you encapsulate your story premise in three sentences, one for the beginning, one of the middle, and one for the end? This is one of my favorite things to tackle on a story premise–although it is arguably the most difficult. This is really where the story concept is actualized.

- The Beginning: A specific character in a specific place/ time faces a specific obstacle

- The Middle: How they react and how the situation progressively complicates

- The End: Whether or not they overcome

Digging Up Your Gem

A book idea is like an uncut diamond sifted from the mud, raw material full of potential. Inside this jagged crystal are inherent possibilities, but not limitless possibilities.

Not every diamond crystal has the potential to be the next World’s Largest Diamond, just as every story concept doesn’t have the potential to be the next Pulitzer Prize Winner.

But who cares?!

Stories, like diamonds, don’t need to be colossal to dazzle and delight. They only need to realize their best size and shape. Keep this permission in mind as you vet your concept.

Digging Tools for Your Book Idea

In order to answer your Six Core Questions, you’re going to have to uncover more of your idea. Here are lenses to look through and tools for tapping and tinkering.

Start with What You Know. I don’t mean this in the cliche write what you know, simply which part of the story idea came first? What piece did the Muse reveal to you?

- Did you get a character?

- Did you get a setting?

- Did you get a “what if” question?

- Did you get a scenario? A scene? A conversation?

Whatever you’ve got, write it down. If you’re looking at an idea that you’ve already developed, decide which elements feel essential and which are negotiable? (Insert heart-wrenching “Murder Your Darlings” quote here.)

A complete story needs a setting, protagonist, antagonist, wants/needs, conflict…and so much more. So start with what you know and extrapolate. What else can you deduce? It’s like algebra for Story (but so much more fun than regular math). If you know x, solve for y. If you know y, solve for x. When you know x and y, solve for z.

Solving for x is asking what else would be interesting? What would progressively complicate the situation? It’s brainstorming causes and effects for essentially any part of the story.

List 30 Bad Ideas. When trying to solve your story algebra, give yourself permission to throw spaghetti string ideas at the wall and see what sticks. Make a list of characters, scenarios, settings, etc. A hearty list. Full of bad ideas. We intentionally embrace bad ideas because this inevitably leads to good ones. It is precisely the fear of bad ideas that stop us from coming up with fresh innovations.

Get Specific. Don’t be afraid to get specific. Not only does this lead to better ideas, it’s the heart of meaningful stories. Without specifics, we can’t be empathetic, and without empathy, we can’t experience the depth and value of a story. Even a purely external Action story requires we be bought-in when the hero is up against life/death stakes. But high stakes does not a vague villain in a vague setting make.

Try-on a Genre. You likely already know what kind of story you want to write, but how would your concept play out as a love story? Action? Thriller? Domestic drama? Do this with both external and internal genres, and keep swapping out to find interesting pairings. A Crime story with a Worldview/Education plot and a Crime story with a Morality/Punitive plot would be two very different stories.

Actualize the Arc. Use the values at stake to envision the plot arc and character arc. In Story, Robert McKee illustrates how to determine a range of values:

- Positive value (Love)

- Contrary value (Indifference)

- Contradictory value (Hate)

- Negation of the Negation (Hate masquerading as love)

There are other values that exist in this spectrum too—some negative, some positive: Repulsion, Attraction, Commitment, Intimacy.

All told, we have a nice wide range of values for our story events to traverse:

- Intimacy

- Commitment

- Love

- Attraction

- Indifference

- Repulsion

- Hate

- Hate Masquerading as Love

Your story may or may not cover the entire range, but again that is a choice based on your story specifics.

Package it to Share. Articulate the concept enough where you can share it with others in writing. Whether this takes the form of a logline, query letter, synopsis, whatever–writing in a way that requires you to communicate the basics to other people. You may have to start out writing more and then gradually honing it down to its essence.

Test Drive Your Idea. Actually share your concept with others and gauge their reactions. Are they excited? Asking pertinent questions of interest. Or are they confused? Bored? The goal would be for your concept to evoke curiosity or concern. “That sounds nice, dear” is not a good sign.

The Truth and Nothing But the Truth

You’ve done it. Gotten real with yourself, embraced that ideas need vetting before you dive into drafting 100k words or create a beat-by-beat treatment of every single scene. You’re turning pro, my friend.

Using all the brain data you’ve acquired, Answer your Six Core Questions.

Also, remember your gem doesn’t have to rival the Crown Jewels. So if you’re doubting the concept holds enough of the Right Stuff to sustain a novel, consider perhaps the problem isn’t that the story doesn’t work at all, it just doesn’t work on that scale. Some gems are more beautiful when we allow them to be cut smaller–into a novella, short story, blog post, short film, or short talk.

All that said, what’s your answer? Does this story concept have the necessary girth to make you go all-in?

Yes, This Story is Worth the Investment.

Great! Next up: get a first draft.

The first draft is the next major milestone where we unleash our arsenal of Story Grid Tools. But, again, I caution you against just going straight for the page, even if you are the pantsy-est of Pantsers. Best to prime yourself for that monster first draft.

There are essentially two approaches: Macro to Micro or Micro to Macro. Check out Lori’s post from last week for more details on how to tackle these two methods.

No, This Idea is Better Left Unwritten.

This can be a disappointing conclusion to reach. But all is not lost. Often when you put an idea away, it continues to bake. Perhaps through writing your next idea, the missing element you need for this concept will find its way to the surface. Or perhaps it’s you who needs to develop.

Whatever it is that’s telling you to not to pursue this idea right now, rest easy. There is no limit on the number of great ideas you’ll have in your life. Just remember, the Muse favors the working.

Final Thoughts

Stephen King says stories are artifacts we dig up rather than create, which is clearly a metaphor I love because I framed this post around it. But as a beautiful and compelling the thought (which honestly takes a lot of pressure off) we must not fail to recognize our direct authority as writers.

As writers, we dig up and unearth amazing ideas, but the idea doesn’t stay “as is”. Our job as writers (and editors) is to then get to cut and polish until they take on their best shape. Often this means abandoning some portion of the idea in favor of something else. The problem is writers get married to their first-born version of the idea, when it’s the 27th iteration that works.

In Story, Robert McKee says:

“Finally, it’s important to realize that whatever inspires the writing need not stay in the writing. A Premise is not precious. As long as it contributes to the growth of the story, keep it, but should the telling take a left turn, abandon the original inspiration and follow the evolving story. The problem is not to start writing, but to keep writing and renewing inspiration.”

You’re not stuck with what you started with–you have the ultimate control. You can change literally anything. After all this, the ultimate test of whether an idea is worth pursuing comes down one thing–you.

How much do you want to write this story? Are you willing to invest all the effort, blood-sweat-and-so-many-tears to see it through?

Even a well-developed idea with commercially viable potential needs this final test. A ready-made story that puts you to sleep or makes you avoid writing–you know, more than the usual amount–is it really worth pursuing?

As Greg McKeown mantras in his book Essentialism, “If it’s not a hells yes, it’s a no.”

On the flip side, if it is a hells yes, well, that’s really all there is to know.

An idea full of holes that is unconvincing to everyone but you, but still you can’t not write it…get through the first draft and then let’s see. Again, that’s the beautiful (and painful) part of this whole writing gig–you get to choose.

But perhaps the most beautiful part is this: even if you pursue a meh idea, take 12 months to draft 100k words (if you’re lucky), revise for three years, and decide to drawer it…it’s never time wasted.

Every pursuit of storytelling is clocking on our 10,000 hours. Even when your story fails, you win. And without failure, what then do we fear?

Now that’s a Going-Pro perspective.

So get to digging. Your diamonds await you.