Download the Math of Storytelling Infographic

In Malcolm Gladwell’s book Outliers, he proposes that it takes 10,000 hours of practice to master a skill. If the skill you want to master is writing, what exactly should you do in those 10,000 hours? There are two types of storytelling skills that writers need to practice. We’ll define each of those skills, look at when you should work on one vs. the other, and go over ways to practice and improve both.

The two types of skills to practice storytelling

All of the storytelling skills needed to create a story can be broken into two types:

- Scene work

- Global storytelling

That’s it. Everything else—character development, point of view, plot development, hero’s journey, and more—can be wrapped up into those two categories. If you can do the micro work of writing scenes that start one way and end another, and the macro work of telling a global story that both abides by the conventions of your genre and provides a hook, build, and payoff, you can write a story that readers, listeners, and viewers will enjoy.

What is scene work?

The most basic unit of storytelling is the scene. An average scene is around 1,000 to 2,000 words. In a scene that works something has changed for at least one of the characters in the scene. What do we mean by “something has changed”? Let’s look at two scenes from Suzanne Collins’s novel, The Hunger Games.

In the opening chapter, there are two scenes. In scene one, Katniss Everdeen gets up and goes hunting and scavenging with her friend Gale near their home in District 12. Scene one ends when they sell what they’ve caught and collected around town. In scene two, Katniss and her sister Prim go to the town square for the reaping, a ritual in which young people are chosen to participate in the “Hunger Games,” which will end in death.

Let’s look at scene two first. At the beginning of scene two, no one has been chosen to represent District 12 in the Hunger Games yet. Everyone in Katniss’s family is safe. By the end of scene two, that’s changed. Katniss’s sister Prim has gone from safe to being chosen for the Hunger Games. That’s a punch you in the solar plexus shift. We turn the page because we have to find out how Katniss is going to react to her sister being chosen for almost certain death.

In scene one, there’s something more subtle happening. While Katniss and Gale are literally hunting and scavenging, the shift in the scene is about their relationship, not the action. Gale asks Katniss to run away with him. She turns him down. He then acts like a jerk. Katniss starts the scene enjoying his company and ends it criticizing him about how he treats the mayor’s daughter. We might say her shift is from friendly to distant.

In both of those scenes, something shifts. Prim goes from safe to chosen. Katniss goes from enjoying a friend to criticizing him. Every scene must shift, either through an obvious change, such as life and death circumstances, or through a more subtle change in a human relationship. If you want write a well-crafted novel, the place to start is learning how to write scenes that shift. Only after you’ve learned to write scenes that shift, are you ready to start stringing those scenes together into a larger global story.

What is global storytelling?

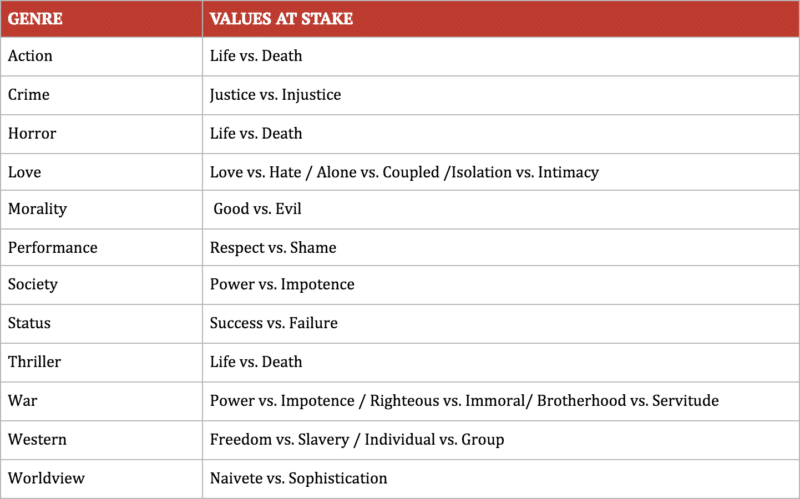

Global storytelling is what we call putting together scenes into an overall story spine. The structure of your story spine, including the key moments you must include, depends on your genre. Your genre also sets constraints on how your story begins, how it ends and how it arcs in between. The table below shows the values a global story will arc between for the 12 content genres.

A global story that works:

- Includes the obligatory scenes that readers expect;

- Satisfies readers’ expectations for the genre conventions;

- Progressively raises the stakes for the characters—in other words, as the story unfolds, the consequences of the protagonist’s choices become more and more irreversible;

- Surprises the reader by alternating between different kinds of scenes; and

- Starts with a beginning that hooks the reader, continues with a middle that ratchets up the tension, and finishes with an ending that reaches a surprising, yet, inevitable conclusion.

When to work on improving your scene work

Whether you should focus on scene work or global storytelling depends on whether you’re new to writing, the kind of feedback you’re receiving on your existing scenes, and the results of a simple test.

If you’re new to writing, you can stop reading and jump straight to the section on how to improve your scene work on your own. That is the place to start. You cannot write a story that works without writing scenes that shift. Because scene work is the foundational skill of all storytelling, it is the first skill to master.

If you’ve been writing for a while, here are some signs that improving your scene work should be a focus:

- It takes you four paragraphs to explain what happens in a 1,500 word scene. A scene that changes can be concisely summarized in two words, a phrase, a sentence or, at most, two sentences.

- You cannot answer the question “what has changed for at least one character in this scene?”

- You give a scene to a friend and they read it. When you ask them to describe the essence of what happens in the scene, they say “I’m not sure.,” “It didn’t go anywhere,” or they go on and on relaying every detail they remember about your scene.

- If you’re working with an editor, the editor says your scenes “don’t work.” What that means is your scene doesn’t include a shift for one of your characters.

Think you’ve got a scene that works? Here’s how to test it. Write down what has changed for one or more of the characters in the scene. Summarize it in a sentence or two. Then give your scene to a writing buddy and ask them to do the same. If you both write similar sentences about what’s changed for one or more of your characters, you’ve probably written a scene that works.

When to work on improving your global storytelling

Once you’re consistently writing working scenes, your next step to practice storytelling is to start thinking about your global story. If you haven’t mastered how to write a working scene yet, improving your global storytelling will teach you just how important that skill is. You’ll discover that if you can’t make a micro scene shift, your global story shift will be impossible. So if you get stuck on the fundamentals of the scene, start thinking globally.

Here are some signs that you have a problem with the global storytelling of your novel:

- Readers have trouble categorizing your story. While a reader may not be able to tell you that you’ve written a steampunk romantic thriller, they should be able to identify that your story is suspenseful, that there seems to be a romance, or that there’s a historical twist. If they can’t do that, you’ve got a global storytelling problem.

- Readers give you feedback, telling you that they felt like “something was missing.” or they specifically say things such as “Why were there no dragons?!”

- Alternatively, readers say things like, “I saw it coming all the way.”, “It felt repetitive.”, or “I didn’t finish it.”

Ready to test your global story? Write down three sentences about your story. The first sentence describes what happens in the beginning of your story. The second sentence is what happens in the middle. The third is what happens at the end. Now ask yourself, in those three sentences, has something changed for my protagonist from beginning to end? Next, look at the table for the values at stake in the different genres. Ask yourself, do my three sentences show a shift in the values at stake for my primary genre? For example, if it’s a redemption story, does the protagonist start morally corrupt and become righteous by the end? If you’ve got three sentences that shift between the critical values for your genre, you’ve got the raw materials for a global story that works.

How to improve your scene work on your own

Learning any new skill is a combination of doing the right kind of practice (deliberate practice) and learning from the masters at the top of your field. Here’s how to improve your scene work when you sit down to write and what to focus on on when you’re reading the best-written books in your genre.

If you’re the kind of writer who likes to plan ahead, here’s how to practice: When you sit down to write a scene, start with an intention. For example, in this scene, I want my protagonist to start out feeling confident in her ability to provide for her family, but by the end, I want her to be unemployed. After you write the scene, evaluate it. Did you shift the scene as you intended? If not, revise.

If your writing process is more free-form—you sit down and write what comes to you without prior planning— focus more on evaluating your work after you’ve written it. What specifically has changed in the scene? For whom? Strengthening the mental muscle that helps you identify the shift is one of the best things you can do as a writer.

Reading masterworks—the best-written books in your genre—is a great way to get ideas and inspiration for your scenes. As you’re reading a masterwork, pay attention to the scenes in those books. Look at the key scenes for your genre (e.g. the Hero at the Mercy of the Villain scene in a Thriller or the Proof of Love scene in a Love story or the Big Battle in a War story or the Big Event for a Performance story.) What was the shift in the scene? Was that what you were expecting to happen? If the author surprised you, how did they do it? Record ideas you have about how to do similar scenes in your story.

How to improve your global storytelling on your own

Just as in scene work there are ways to practice on your own and ways to learn from the masters of your genre in global storytelling. As you’re writing, a good place to start working on your global storytelling is by asking yourself two questions after you write every scene:

- What happens next in this story?

- Does what happened in this scene make sense in terms of what happened before?

Here’s a podcast episode where Tim wrestles with those questions for his novel.

Once you’ve got a full manuscript, it’s time for a more formal analysis of your global story. For each section of your novel—the Beginning Hook (first 25% of your scenes), Middle Build (middle 50%), and Ending Payoff (final 25%)—you’ll want to see a shift from the beginning to the end of that section. How you check to see if you’ve made the necessary shifts is by putting all the major plot points of your novel onto a single piece of paper. That paper is called a Foolscap Global Story Grid. (Here’s a generic Foolscap.) Want an example of how it works? Here’s a podcast episode where Shawn and Tim walk through a Foolscap Global Story Grid on Tim’s completed manuscript.

Ready to learn global storytelling from the master writers? One of the best things you can do is to create a Story Grid spreadsheet of a masterwork in your genre. How do you do that? Here’s a podcast episode where Tim creates a Story Grid spreadsheet of Harry Potter and the Sorcerer’s Stone.

Getting feedback and pushing yourself further

If you’re determined to be a top-notch writer, you’re going to need more than practice on your own. While a lone wolf writer might complete a manuscript, he’s also likely to collect a pile of rejection letters or an Amazon page full of negative reviews for his self-published book. The best way to ensure you have more success as a writer is to get specific, targeted feedback on your scenes and your global storytelling.

When it comes to scenes, the most basic feedback you need is to know if a scene has a shift, or if it doesn’t. Once you know how to write scenes that work, you’ll want feedback that goes beyond the basics to help you see what’s cliché in your genre and to inspire you to brainstorm different combinations of characters, settings, and scene shifts. If your villain was polite instead of overbearing, would that make your scene more unexpected? Would your Lovers Meet scene seem less cliché if it occurred at boot camp, a VA hospital, or on the battlefield? Can your superhero go from captured to freedom in a more surprising way? How can you abide by the conventions of your genre, yet still surprise the reader?

When it comes to global storytelling, a developmental editor can really help. Unless you’ve got a good friend who knows your genre inside and out, you’re going to have a hard time finding someone who can tell you things like “you’re not progressively raising the stakes for your protagonist from chapter 12 onwards,” “you’re missing a Speech in Praise of the Villain scene,” or “all of the supporting characters in your love story are against the pair getting together – you need to add a helper character.” That’s the kind of specific feedback that tells you what is a problem in your global story and what it will take to fix it.

What to do with your 10,000 writing hours

So what should you do during your 10,000-plus hours of novel writing? Today we covered the two types of storytelling skills every novelist needs. The truth is, the best writers are constantly switching between those two skills. Working on writing scenes that surprise as well as shift as well as perfecting the best way to raise the stakes for their protagonist, while also honoring the conventions of their genre. They’re challenging themselves to brainstorm more possibilities and getting feedback so they know where to focus during their writing time.

How are you spending your 10,000 hours of practice? Do you have an intention before you write a scene? Have you tried the three-sentence exercise or made a Foolscap Global Story Grid for your novel? Share your comments and questions below.

Download the Math of Storytelling Infographic

Share this Article:

🟢 Twitter — 🔵 Facebook — 🔴 Pinterest

Sign up below and we'll immediately send you a coupon code to get any Story Grid title - print, ebook or audiobook - for free.

(Browse all the Story Grid titles)