Learning how to write dialogue is an essential part of telling stories that work. Dialogue is a character’s verbal and non-verbal expression of what they are thinking and feeling. It’s through dialogue that other characters get a glimpse into what’s going on in each other’s minds. It’s also used to reveal to the reader those inner thoughts, feelings, and actions that want to come out.

Contrast that with narration, which describes the world in which the characters find themselves in as well as the inner thoughts of potentially some of the characters. It’s through the balance of Dialogue and Narration that the story reveals itself to the readers and characters.

Dialogue is the Yin to narration’s Yang. They both must be present and strengthen each other. Without clear, concise, and compelling dialogue, your character’s authentic self won’t shine through, the tension in your scenes won’t progressively complicate, and all that great narration will be for nothing.

Dialogue must always serve a purpose. It intensifies the action as well as organizes it so that the emotion that people feel in a situation builds up while the characters are processing what’s going on. This real-time processing is important to remember since it’s these beats of processing that build great dialogue.

Types of Dialogue

There are two types of dialogue to think about when you’re writing a story — inner and outer dialogues. Both are important to understand and use depending on the type of characters and the story you’re trying to tell.

Outer Dialogue

Outer dialogue is a conversation between two or more characters. This is the type that is the easiest to identify since the tags and markers are present and it feels like a conversation.

Inner Dialogue

This type of dialogue is when the character speaks to themselves and reveals parts of their personalities or unburdens their soul. Inner dialogue is usually written as a stream of consciousness or dramatic monologue or just thoughts. Sometimes italicized, sometimes not. Sometimes with attributions, sometimes not. The way that inner dialogue is rendered on the page will depend on the POV/Narrative Device choice.

A stream of consciousness type dialogue describes the flow of thoughts in the mind(s) of the character(s). It borders on narration in that there are no dialogue markers or tags per se. It’s usually obvious when it’s happening.

Dialogue Lives at the Beat Level

A story has a nested structure with the smallest level being a beat. The story then builds up to scenes, sequences, acts, subplots, and finally the global story. For dialogue, it’s important to start at the beat level because the action and reaction that the character(s) are doing, based on the dialogue, will change as the scene moves from beat to beat. In the Story Grid universe, we use the Five Commandments of Story to build up these different story parts since they all nest together as you go from micro to macro.

A Quick Review of the Five Commandments of Story

The five commandments of story make up the component parts of a story. These commandments must be present at all levels for each component to work and move the story forward. Briefly, these five commandments are:

- Inciting Incident: upsets the life balance of your lead protagonist(s). It must make them uncomfortably out of sync for good or for bad.

- Progressive Complication(s): move the story forward (never backward) by making life more and more complicated for the protagonist(s). The stakes must progressively get higher and higher until the turning point progressive complication that shifts the life value and prompts the crisis.

- Crisis: the point where the protagonist(s) must make a decision by answering the best bad choice or irreconcilable goods question such as: do I go in the cave or not? Or do I share my true feelings or not?

- Climax: is the answer (the decision plus the action) to the question raised by a crisis.

- Resolution: the results (good or bad) from the answer in the climax

For dialogue, we’ll look at a similar set of commandments or tasks inspired by Robert McKee later on. We’ll also explore a way to analyze dialogue using the tasks and a few other techniques. As we go along, you’ll see why it’s important to think, write, and analyze dialogue at the beat level to build up great scenes, sequences, acts, sub-plots, and finally the global story.

Three Functions of Dialogue

According to Robert McKee, in his book Dialogue: The Art of Verbal Action for Page, Stage, and Screen, dialogue has three functions: Exposition, Characterization, and Action.

Exposition

“Exposition is a literary device used to introduce background information about events, settings, characters, or other elements of a work to the audience or readers. The word comes from the Latin language, and its literal meaning is ‘a showing forth.’ Exposition is crucial to any story, for without it nothing makes sense.”

Literary Devices.net

This trick with exposition is that too much information is hard for our brains to process. That’s what gives rise to the exposition is ammunition recommendations all writers hear. A story needs exposition to drive the story forward yet too much will distract, especially in dialogue, from the pace and flow of the story. It’s these fictional or non-fictional facts of the set (character mindset) and setting (environment) that gives the reader what the characters are experiencing and reacting too. It’s important to pace and time your exposition to not reveal too much too soon. You also have to take great care and skill to make the details of the character come alive in unique and novel ways so you keep the reader interested, which leads to another tried and true piece of advice — remember to show and not to tell.

Characterization

The sum of a character’s traits, values, behaviors, and beliefs. It’s how the author creates the character(s) in the reader’s mind. It’s through characterization that we can see and feel how the character(s) will react and interact.

Action

What a character does — mental, physical, and verbal. Action reveals what cannot be understood otherwise or would sound awkward to describe. Again show don’t tell. The action is what keeps the story interesting and moving along.

Six Tasks of Dialogue

All dialogue must have a purpose and perform one of the three functions. Within these functions, a great beat of dialogue will complete these six tasks (taken from McKee’s Dialogue):

- Express Inner Action (Essential Action in Story Grid terms)

- Action/Reaction

- Conveys Exposition

- Unique Verbal Style

- Captivates

- Authentic

Let’s take a look at each one to see how they build up to great dialogue. For each, I’ll give an example of dialogue that completes the task from this wonderful article Ten Authors Who Write Great Dialogue.

Task #1: Express Inner Action

Each verbal expression requires an internal action to make it happen. These inner actions or essential action in Story Grid terms are how the character responds to the outside world’s stimulus as well as their own past experiences. The interaction of external stimulus and character subtext (past experiences) will create this inner action. This would be the essential action that the character wants to express or the goal they are trying to achieve. The example is from Douglas Adam’s The Hitchhiker’s Guide to the Galaxy:

‘Drink up,’ said Ford, ‘you’ve got three pints to get through.’

‘Three pints?” said Arthur. ‘At lunchtime?’

The man next to Ford grinned and nodded happily. Ford ignored him. He said, ‘Time is an illusion. Lunchtime doubly so.’

‘Very deep,’ said Arthur, ‘you should send that in to the Reader’s Digest. They’ve got a page for people like you.’

‘Drink up.’

Ford’s goal is to get Arthur to ‘drink up’, for what reason we don’t know, but for this beat, it’s pretty clear.

Task #2: Action/Reaction

Once a character takes action, there will be a reaction. This action/reaction dance will lead to the ultimate turning point of the scene between the characters. As the tension in a scene builds from beat to beat, so should the dialogue. The dialogue should stir up the emotions of the characters so there will be a desire to express more and more extreme inner actions.

Let’s look again at the same example from Task #1. The Action/Reaction between Ford and Arthur escalates as Arthur complains that it’s too early to drink yet Ford prods him on by saying that ‘Time is an illusion. Lunchtime doubly so.’

Task #3: Conveys Exposition

What a character says, does not say, and how they say it will reveal exposition. The revealing of exposition in unique and novel ways is what separates good dialogue from great dialogue. For example, Judy Blume does this to great effect in this piece of dialogue from her book Are You There God? It’s Me, Margaret.

Nancy spoke to me as if she were my mother. ‘Margaret dear–you can’t possibly miss Laura Danker. The big blonde with the big you know whats!’

‘Oh, I noticed her right off,’ I said. ‘She’s very pretty.’

‘Pretty!’ Nancy snorted. ‘You be smart and stay away from her. She’s got a bad reputation.’

‘What do you mean?’ I asked.

‘My brother said she goes behind the A&P with him and Moose.’

‘And,’ Janie added, ‘she’s been wearing a bra since fourth grade and I bet she gets her period.’

To the teenage reader, the line ‘My brother said she goes behind the A&P with him and Moose’ says a lot about Laura Danker and why she has a bad reputation without saying what goes on behind the A&P.

Task #4: Unique Verbal Style

Each character will have a unique verbal style that they used to communicate their inner actions. This verbal style must be appropriate for the set and setting the characters find themselves in. This tone and tenor of their voice along with word choice (or lack of words) must be on theme for the character. The reader must say to themselves, “yeah, they would say that that way.” For this example, we’ll look at Barbara Kingsolver’s The Poisonwood Bible.

With all due respect,’ my father said, ‘this is not the time or the place for that kind of business. Why don’t you sit down now, and announce your plans after I’ve finished with the sermon? Church is not the place to vote anyone in or out of public office.’

‘Church is the place for it,’ said Tata Ndu. ‘Ici, maintenant, we are making a vote for Jesus Christ in the office of personal God, Kilanga village.’

Father did not move for several seconds.

Tata Ndu looked at him quizzically. ‘Forgive me, I wonder if I have paralyzed you?’

Father found his voice at last. ‘You have not.’

Tata’s unique verbal style shows that English is his second language and as such, he means to not offend the priest giving the sermon. Equally unique is the priest that gives this dialogue the contrast it needs to know who is talking.

Task #5: Captivates

Dialogue must do work. It is not normal everyday speech. Great dialogue captivates the reader by being clear, concise, and compelling. There is no shoe leather or wasted words, movements, or expressions. It’s hyper speech in that, as the writer, you can think about every word.

Looking at the example from Task #4, it’s clear that there is some tension between the characters. There are no wasted words in what Tata wants to accomplish and the tension between Tata and the priest is made more by Tata’s line ‘Forgive me, I wonder if I have paralyzed you?’

Task #6: Authentic

All dialogue must sound like the character would say it. Dialogue that falls flat or does no work will have readers saying “the character in the book would never say that.” An authentic character voice starts with a solid story and character design where the reader knows the character and will anticipate how they will express their inner/essential action. Inner/Essential action comes from a character’s authentic voice. For this task, we’ll look at some dialogue from Elmore Leonard’s Out of Sight:

‘You sure have a lot of shit in here. What’s all this stuff? Handcuffs, chains…What’s this can?’

‘For your breath,’ Karen said. ‘You could use it. Squirt some in your mouth.’

‘You devil, it’s Mace, huh? What’ve you got here, a billy? Use it on poor unfortunate offenders…Where’s your gun, your pistol?’

‘In my bag, in the car.’ She felt his hand slip from her arm to her hip and rest there and she said, ‘You know you don’t have a chance of making it. Guards are out here already, they’ll stop the car.’

‘They’re off in the cane by now chasing Cubans.’

His tone quiet, unhurried, and it surprised her.

‘I timed it to slip between the cracks, you might say. I was even gonna blow the whistle myself if I had to, send out the amber alert, get them running around in confusion for when I came out of the hole. Boy, it stunk in there.’

‘I believe it,’ Karen said. ‘You’ve ruined a thirty-five-hundred-dollar suit my dad gave me.’

She felt his hand move down her thigh, fingertips brushing her pantyhose, the way her skirt was pushed up.

‘I bet you look great in it, too. Tell me why in the world you ever became a federal marshal, Jesus. My experience with marshals, they’re all beefy guys, like your big-city dicks.’

‘The idea of going after guys like you,’ Karen said, ‘appealed to me.’

The man character in this dialogue is an outlaw who escaped from prison and would say and do what this character is doing. As for Karen, this bit of dialogue reveals a lot of exposition as well as the type of person a female federal marshal might be.

Five Stages of Talk (Dialogue)

All verbal action and behavior move through stages of steps to come to life. These stages go from desire to antagonism to choice to action to expression. For our purposes, we’re going to use these stages like the five commandments of story to ensure that as we analyze and write dialogue, we have an objective framework to apply (again from McKee’s Dialogue).

#1 Desire

What the character wants to achieve in the scene or the essential action or the goal. Mostly, it’s to get back to a life balance that has been disrupted from the status quo or the character’s object of desire. Background desires will limit the character’s choice because they limit what the character will or will not do. More on background desires when we get into the analysis.

#2 Sense of Antagonism

What is preventing the character(s) from getting back to balance? What or who is in their way? The sense of antagonism is what the character is reacting to and is usually who they are dialoguing with.

#3 Choice of Action

The action the character wants to take to get to the desired scene intention based on their desires or inner actions. The choice of action has to be authentic to the character so that the series of possible actions or best bad choices make sense to the reader.

#4 Action/Reaction

The actual or literal action they take be it physical or verbal and the reaction that might occur. Desire is the source of action, and action is the source of dialogue. All are governed by the character’s subtext or past experiences.

#5 Expression

The verbal action as dialogue coupled with any physical activity that might also express the actions of the character (e.g. narration of expression, physical act like screaming, stepping forward, clenching a fist, etc.). The expression must be authentic to the character and as such, the reaction to the expression by another character(s) will drive the action/reaction to the turning point, crisis, climax, and finally resolution.

Dialogue Analysis

Before we get to the mechanics of writing dialogue, let’s take a look at a framework to analyze existing dialogue so we can better understand its structure. This analysis framework consists of the following:

- Character(s) Agenda + Voice (Macro)

- Pre Beat/Scene Character(s) Subtext (Micro)

- Five Stages of Talk (Micro)

- Post Beat/Scene Character(s) Subtext (Micro)

The first item on this list operates at the macro-level (e.g. scene, sequence, etc) while the last three operate at the micro or beat level.

Character(s) Agenda/Subtext + Voice

Character subtext or past experiences are what drive the expression of dialogue since they are what generate the inner action. A character’s subtext, their authentic voice, and their abilities to manifest action will constrain their expression. These guardrails of expression are what have to be considered when writing character dialogue. This is why it’s vital to have a solid story structure and character studies to guide your character’s dialogue.

A character study is a description of the character that includes age, gender, physical appearance, internal and external struggles, quirks, etc. It’s a great way to ground a character’s dialogue since you want every word that comes out of a character’s mouth to be consistent with who they are and in their voice. It’s also their history along with character traits, values, beliefs, and skills that are the guardrails in which they can express their inner/essential actions.

A character’s voice will also be unique to them. The more of a contrast in voice between characters, the more tension and the easier the reader can follow who is saying what. If characters have a similar voice (e.g. sound or act the same), it will be harder for readers to keep track. Of course, you can use tags and markers to set off who is talking but as the reader gets to know the characters, it should become extremely clear who the characters are based on what they say and do.

Pre Beat/Scene Character(s) Subtext

The character study above is a macro level synopsis of the traits, values, beliefs, quirks, and skills that a character has. All of these parameters may or may not come into play at the Pre Beat/Scene level since all characters arrive at a beat with a macro-history and micro-history.

As I mentioned before, the macro history is the guardrails of their action or what will be in character for them to do while the micro-history what happened before the beat/scene they are about to come into. It’s these micro-histories that will shape how the character acts at the moment. For example, if the character comes to the beat tired or hungry, they will have a different action/reaction than if they were fed and well-rested.

Five Stages of Talk

Each beat of a scene should follow the five stages and build on each other. If one or more of the stages is missing or not as strong, the dialogue is not doing its job. Again, dialogue is not real-life speech and it must not meander or build up like people talk in real-life with all the um’s and likes and on the nose exposition that real-life speech can have when a person is trying to figure out what to say. For a character, the writer can bypass all that at the moment thinking to deliver what the character wants to say. Every word must be intentional and mean something to the characters and the story.

Post Beat/Scene Character(s) Subtext

After each beat, the character(s) subtext has changed in some way since their inner action has been expressed or some new exposition has been revealed. These new facts need to be considered for the next beat or scene since it’s the sum of the character(s) experiences.

Dialogue Analysis Examples

Let’s take a look at a few examples of dialogue and how the analysis framework can be applied.

Example #1 — Fargo

For our first example, we’ll look at the movie Fargo that we analyzed on the Story Grid Roundtable Podcast. I picked this as the first one because it clearly shows the five tasks of dialogue as well as the pre and post beat subtext, which changes substantially from the start to the end of the scene.

Character(s) Agenda + Voice: Carl and Gaear want to get to the hideout after kidnapping Jean. Carl is a highly-strung, talks too much know-it-all while Gaear is the strong/silent but deadly type.

Pre Beat Subtext: Kidnappers Carl and Gaear are taking their victim Jean to the hideout. They get pulled over on the highway for not having a license plate. Carl and Gaear want to deceive the trooper so he does not find Jean. This scene takes place at 0:27:33 after they get pulled over on the highway.

Dialogue:

CARL: How can I help you, Officer?

TROOPER: Is this a new car then sir?

CARL: It certainly is, Officer. Still got that smell

TROOPER: You’re required to display temporary tags, either in the plate area or taped to the inside of the back window.

CARL: Certainly

TROOPER: Can I see your license and registration, please?

CARL: Certainly. Yeah, I was gonna tape up those … The tag. You know, to be in full compliance, but it must have [CARL shows a $50 to the TROOPER] … must have slipped my mind. So maybe the best thing to do would be to take care of that right here in Brainerd.

TROOPER: What’s this sir?

CARL: My license and registration. Yeah, I want to be in compliance. I was just thinking we could take care of it right here, in Brainerd.

TROOPER: Put that back in your pocket please, and step out of the car, please, sir.

[TROOPER hears Jean whimpering. Looks in the back and Gaear smashes his head then shoots him dead.]

CARL: “Whoa. Whoa, Daddy.”

Five Stages:

- Desire: Carl wants to get to the hideout with Jean without being caught.

- The Sense of Antagonism: The Trooper.

- Choice of Action: Carl tries to talk his way out of the trooper sniffing around by hinting at a bribe.

- Action/Reaction: Carl presents his wallet with a $50 sticking out of it. The Trooper senses the bribe and asks Carl to “put that back in your wallet and get out of the car.”

- Expression: Carl looks at Gaear, wondering what to do. Gaear smashes the cop against the car and shoots him dead.

Post Beat Subtext: Gaear killed the trooper and now they need to take care of the body and get out of there quickly. Carl is clearly upset about what happened and now knows, more than before, that Gaear is a psychopath.

Example #2 — Pride & Prejudice

Jane Austin’s Pride & Prejudice is the masterwork in the Love > Courtship genre. Her use of dialogue makes the story flow and gives great scenes like the one below between Mrs. Bennet and Mr. Bennet.

Character(s) Agenda + Voice: Mrs. Bennet wants to marry off one of her daughters to Mr. Bingley. Mrs. Bennet is quite excitable so her voice is high pitched and fast. Mr. Bennet is a serious man but loves to give his wife a hard time since he knows that she’s a gossip.

Pre Beat Subtext: We are introduced to three of the Bennet sisters and how obsessed Mrs. Bennet is with marrying them off to good men so the family can be taken care of.

Dialogue:

“What is his name?”

“Bingley.”

“Is he married or single?”

“Oh! Single, my dear, to be sure! A single man of large fortune; four or five thousand a year. What a fine thing for our girls!”

“How so? How can it affect them?”

“My dear Mr Bennet,” replied his wife, “how can you be so tiresome! You must know that I am thinking of his marrying one of them.”

“Is that his design in settling here?”

“Design! Nonsense, how can you talk so! But it is very likely that he may fall in love with one of them, and therefore you must visit him as soon as he comes.”

Five Stages:

- Desire: Mrs. Bennet wants to know more about Mr. Bingley for her daughters.

- The Sense of Antagonism: Mr. Bennet’s apathy to doing so

- Choice of Action: Mrs. Bennet wants to know as much as she can about Mr. Bingley

- Action/Reaction: Mrs. Bennet tells Mr. Bennet that she is thinking that Mr. Bingley would be a good match for one of her daughters. Mr. Bennet is skeptical.

- Expression: Mrs. Bennet wants Mr. Bennet to inquire right away and is adamant about him doing it quickly.

Post Beat Subtext: Mr. Bennet will be pestered by Mrs. Bennet until he goes for a visit to inquire about Mr. Bingley’s status.

How to Format Dialogue

The rules for formatting dialogue are straightforward for 90% or so of the dialogue you’ll write. It’s best to start with the simple and expand as you get better at writing dialogue. There are two formats to consider when writing dialogue — what tag or markers to use and proper punctuation.

Dialogue Tags

A dialogue tag is a small phrase either before, after, or in between the actual dialogue itself to communicate attribution of the dialogue (e.g. who is speaking). The most common tags are said and asked with the most common placement being after the dialogue as in:

“Can you come here?” Jane asked.

“I’m on my way,” Jack said.

There is some debate as to the types of tags or a variety of tags that should be used. This centers around whether adding the actions to the characters as opposed to adding the narration after the tag as follows:

“Can you come here?” Jane yelled from the other room.

“I’m on my way,” Jack shouted back.

Compare that to:

“Can you come here?” Jane asked. Her voice echoed as she yelled from her home office, which was added last summer.

“I’m on my way,” Jack said. His low baritone rattled the windows in Jane’s office.

I don’t think there is any right answer to what to do but I would add that it will depend a lot on what type of pace you want your dialogue to take.

For rapid-fire dialogue, the amount of complexity in the tags and narration will slow it down but also can reveal exposition about the characters as illustrated in the last example.

The set and setting of where the dialogue takes place will affect the tone and tenor between the characters. These variables affect the pace and the variety of pace in a story makes it more interesting and engaging. We’ll talk more about that in how to write captivating dialogue.

Punctuation

Dialogue punctuation rules are simple. There are two parts that need to be punctuated: the actual dialogue, which identifies the words spoken, and the dialogue tag, which identifies who is speaking. The basic rules of dialogue punctuation are as follows:

- Surround your dialogue with quote marks and add a comma before closing the quotes if you’re using tags.

- Create a new paragraph for new speakers.

- Put periods inside of quotation marks when not using dialogue tags.

These basic rules should get you most of the way to properly formatted dialogue. This excellent post from Thinkwritten will get you the rest of the way.

How to Write Dialogue That Captivates Readers

Captivating dialogue is effortless for the reader to read and digest. It never gets in the way, always feels natural, and is in the authentic voice of the character. In order to do that, we’ll apply the captivating dialogue framework to write the dialogue and if needed, we follow that up with the analysis. Not all dialogue you write will require analysis so don’t feel like you have to look at every single beat of dialogue. Rather, save the analysis method for when you’re stuck or the dialogue is not working.

Captivating Dialogue Creation Framework

At the Story Grid, we like frameworks and objective ways to craft stories. For us, this is the best way to have a consistent process of creation, where if we follow the process, we have a better shot at creating a story that works. The same goes for dialogue.

The importance of this process-driven methodology comes to light when a story or beat of dialogue has problems. Since we rely on objective measures, usually we can pinpoint the problem and provide a solution. For dialogue, I propose the following framework:

- Genre Specific Conventions, Scenes, Tropes, and Styles

- Character Studies + Annoying Quirks + Authentic Voice

- Ramp up Conflict + Tension

- Weave Subtext using Exposition

- Balance Dialogue/Narration for Pace

- Read it Aloud

- Analysis when needed

#1 Genre Specific Conventions, Scenes, Tropes, and Styles

All writers need to pick a genre. Genre selection will then lead to the conventions, obligatory scenes, tropes, and styles that readers of the genre are expecting. This list of requirements allows the writer to already have scenes and tropes that will give hints for great dialogue.

For example, if your story is in the Love > Courtship genre, then one of the Obligatory Scenes is when the lovers meet — you can’t have a love story without lovers. The dialogue between the lovers needs to convey some form of either interest or hate or a combination of both. When they talk about the potential suitor to others, the exposition of interest or annoyance or lust comes through in the dialogue. Or in contrast between inner and outer dialogue: what they say to others versus what they admit to themselves. Much of this will depend on the POV you’re using.

In terms of scene tropes, any Crime story usually has a scene in a police car or station house. The words the police use will be in a certain style and readers will expect the good cop/bad cop or a police car ride or an integration scene trope.

#2 Character Studies + Annoying Quirks + Authentic Voice

Once you have settled on your genre, you’ll need to figure out the characters in your story. For convenience, we’ll assume that all stories will have at least a victim, a villain (antagonist), and a hero (protagonist). These three characters will clearly talk to each other at some point and need to have enough of a difference so that it’s clear who is talking even without dialogue tags.

A quick character study of a few paragraphs describing the character along with some character-specific quirks will set the tone for how they speak. It’s always a good idea to have character quirks that annoy other characters so that the tension is built into every interaction.

For example, in the Fargo scene we looked at before, Carl and Gaear have quirks that get on each other’s nerves. Carl talks too much. He thinks he’s the smartest of the two. Gaear is quiet and reserved but will resort to violence when he is annoyed. This makes Carl nervous so he talks more thus annoying Gaear even more. As the movie progresses (spoiler alert), Carl annoys Gaear to the point where Gaear shoots and kills him. Talk about ramping up the conflict + tension.

#3 Ramp up Conflict + Tension

Dialogue should moderate the pace of the story and the best way to do that is to ramp up the conflict and tension between characters. All dialogue should perform the six tasks and conflict is the best way to accomplish that.

The true nature of a character (and frankly people in real life) are revealed under stress and strain. The inner action that’s under control one minute will suddenly explore out when the conflict or tension is ramped up. Great dialogue will masterfully “power of ten” the conflict and tension to a crisis and climax that will surprise and delight the reader (or viewer).

Another way to think of this conflict and tension ramp is to imagine you’re a director of a movie. The actors are in the scene and you’re trying to visually capture the energy of the scene. At your disposal is the shots the camera can get. Wide shots. Narrow shots. Split shots. Out of focus shots. All of these pieces of the scene can be used to reveal what the characters are doing. The same goes for written dialogue.

Being able to “move the shot” around in your dialogue will give different ways to ramp up the conflict or change the pace. Being specific about a certain detail or use of a word or even a group of people off in the distance can make a difference. That’s what’s done in this Die Hard Scene. Image how you would write this into a script or novel:

HAN GRUBER: [On the radio] You are most troublesome for a security guard.

JOHN MCLANE: [Imitates buzzer] Sorry, Hans. Wrong guess. Would you like to go for double jeopardy where the scores can really change?

HANS GRUBER: Who are you, then?

JOHN MCLANE: Just a fly in the ointment, Hans. A monkey in the wretch. A pain in the ass.

It’s a simple exchange but it ramps up the tension and also reveals John’s character, Han’s character and the exposition that John is going to cause all sorts of trouble for Hans. We don’t know how yet and that’s what makes us want to keep watching.

#4 Weave Subtext using Exposition

When characters are under stress and strain, it’s easier for them to reveal hidden secrets or details that they might not want to reveal. It’s these “oops” moments or a reflective moment that makes great dialogue. These moments are what is meant by using exposition as ammunition to reveal character quirks, subtext, and story details.

The challenge is to not make the exposition reveal too obvious or boring or “on the nose.” That type of dialogue will distract the reader from the story and harms the flow of the story. As an example, look at this passage from Little Red Riding Hood to see how exposition is used to reveal story details.

“You will need to wear the best red cloak I gave you,” the mother said to her daughter. “And be very careful as you walk to grandmother’s house. Don’t veer off the forest path, and don’t talk to any strangers. And be sure to look out for the big bad wolf!”

“Is grandmother very sick?” the young girl asked.

“‘She will be much better after she sees your beautiful face and eats the treats in your basket, my dear.”

“I am not afraid, Mother,” the young girl answered. “I have walked the path many times. The wolf does not frighten me.”

This beat of dialogue foreshadows what is to come and while maybe not as subtle as it could be, it gives the reader the necessary background to create tension as the girl sets off to grandma’s house.

#5 Balance Dialogue/Narration for Pace

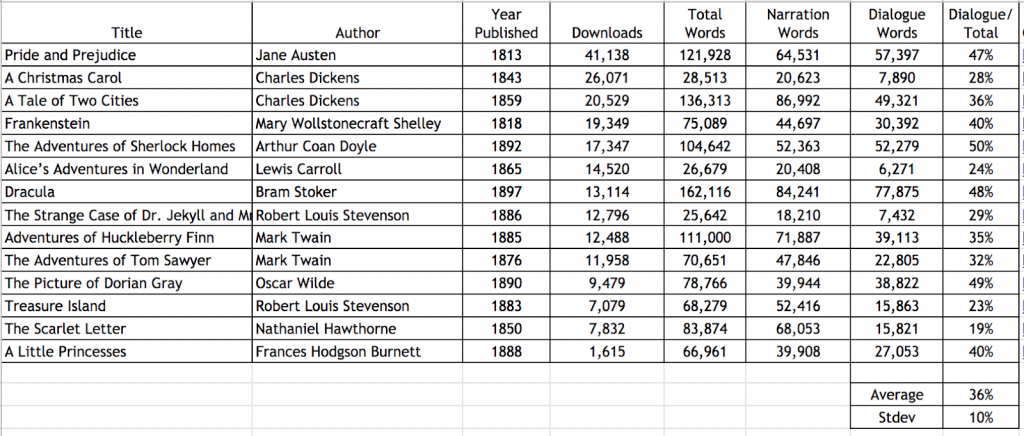

Dialogue does not live in a vacuum. It needs narration to give subtext, explain the physical world, and to set up the situations our characters find themselves in. While there are no hard fast rules on the split between dialogue text and narration text, I did a brief study of 14 books from Project Gutenberg. See below for the statistics.

A perfect split between dialogue words and narration words would be 50%. Anything below 50% would be more narration. Anything above 50% would be more dialogue. As you can see from the sample, there tends to be, on average, more narration than dialogue. This intuitively makes sense since narration sets up dialogue and most dialogue uses tags or markers to set it off. My guess is that the Dialogue/Narration ratio will depend on the genre, so take these numbers as such.

Another consideration on the Dialogue/Narration spectrum is the pace of the story. In general, the more narration in a scene, the slower the pace while more dialogue will tend to make the pace faster. That’s one of the reasons that dialogue is not real-life speech. It is stylized speech in which the author, through the characters, has a purpose for each word. When dialogue hits its mark, the pace of the story quickens because all of the sub-text, narration setup, and stylization reveals the character(s) inner action in the least amount of words.

When writing dialogue, it’s good to mix up the dialogue/narration ratio so that the reader can feel the pace quicken or take a break to internalize and synthesize what just happened. This variety in dialogue will keep readers interested and yearning to find out what happens next since story is about change and the way a story changes should be varied.

#6 Read it Aloud

Nothing gives you a better sense of the tone, tenor, and pace of dialogue like reading aloud, preferably in each character’s unique voice and accent (if present). Reading dialogue aloud will connect the words on the page with the processing in your brain. What I mean by this is that when you verbalize dialogue, your attention is heightened because you have to read then speak. That’s a different pathway than the normal shortcuts most people take while reading, skipping connector words or full-on sentences.

#7 Analysis When Needed

Not all of the dialogue you write will need a detailed analysis discussed above. My guess is that the more dialogue you write, the better you’ll naturally ask yourself the important questions about raising the conflict by power of ten, revealing exposition, keeping a consistent character voice, and distilling the words characters say into tight interactions.

If you do get stuck, then doing the analysis will get you unstuck. Remember that dialogue that’s not working is usually rooted in a fundamental story problem and my guess is that the analysis will reveal an underlying story problem that will need to be fixed.

Pitfalls to Look Out For

Most dialogue pitfalls come from not setting up the subtext enough so that the characters can express their inner action in their authentic voice. Usually, it’s obvious when the exchange is read aloud but sometimes the writer can get so consumed with the process that even an aloud read can’t find it.

The analysis framework will likely catch any problem but as I mentioned before, it can be cumbersome to apply to all your beats of dialogue. That’s why I have come up with a couple of spot checks for your dialogue to quickly catch the majority of the pitfalls that writers run into.

- Confusion on Who’s Talking: This is especially problematic with more than two people talking. Use the tags liberally to get the flow and then fine-tune in later drafts.

- Cursing: Too much cursing takes away from the power of the words and will bore the reader. That does not mean that a well-placed f-bomb will not hit the mark.

- Improper use of Period Speech/Mixing of Speech: If you’re writing period pieces, then getting the words right matters.

- Misusing Humor: Humor is hard to write and should be used sparingly unless you’re writing a comedy. Pay particular attention to jokes that are meant to break the tension since those are the hardest.

- Variety of Dialogue Tags: Don’t get carried away with having to mix up different dialogue tags. When in doubt, use said and asked. Having too many different dialogue tags can wear out the reader.

- On the Nose Dialogue: Avoid stating the obvious or what the characters already know. This is the classic telling problem where the action of the character is more important than them telling the other character what they are doing.

Your best tool for catching dialogue problems will be reading it aloud over and over again so that you get the tone and tenor of the character’s authentic voice down cold. It’s also good practice to step away from the dialogue so you can look at it fresh after doing something completely different.

Dialogue Writing Prompts

The framework above is a good way to create dialogue once you have an idea. Sometimes, those ideas are hard to come by. That’s why having a few go-to writing prompts will make the creation process a little easier. The best resource I found for prompts comes from Daily Writing Tips and their post 70 Dialogue Writing Prompts. At the end of the post, they also have a list of additional resources for even more prompts. The ones I have listed below are a sample of what Daily Writing Tips has as well as the other resources. The sources are denoted in brackets.

- “Ma’am, I’m afraid I’ve got some bad news. Please, sit down.” [Daily Writing Tips]

- “This is going to be way harder than we thought.” [Daily Writing Tips]

- “Oh man, I’ve had the worst day ever.” [Daily Writing Tips]

- “You must have misheard me.” [Daily Writing Tips]

- “If you could just set it down – very slowly – and then back away.” [Daily Writing Tips]

- “Do you maybe think, in retrospect, that this was a terrible idea?” [Daily Writing Tips]

- “I’m so sick of all this gloom and doom. Why can’t people just be happy?” [Marylee McDonald]

- “You’re going in there right now and apologize.” [Marylee McDonald]

- “I’m asking because I’ve seen the way you look at me.” [A Cure for Writer’s Block]

- “Will you stay the night?” [A Cure for Writer’s Block]

- “I want to spend the little time I have left with you and only you.” [A Cure for Writer’s Block]

- “Sometimes, being a complete nerd comes in handy.” [Chrmdpoet]

- “How much of that did you hear?” [Chrmdpoet]

- “People are staring.” [Chrmdpoet]

Hopefully, you won’t need to use too many prompts. Again, dialogue problems are usually story problems so if your story structure and character design is solid, then your dialogue should follow. If you get stuck and can’t figure a way out, then read one of the masterworks in your genre for inspiration. Chances are, those stories will inspire you and get you past your block.

The Golden Rule of Dialogue

Dialogue problems are story problems. If you feel that your dialogue is weak or lackluster, chances are, your story fundamentals are not in place. Luckily, you’re reading this on the Story Grid and we can help.

The Story Grid is a framework for telling better stories. It exists to help writers objectively evaluate their stories to see what’s working and what’s not. The best place to start is the editor’s six core questions and the five commandments of story. These macro and micro tools will give you some keen insights into where your dialogue problems are coming from.

If you’re like me, then most of your dialogue problems will come from not setting up scenes properly (five commandments), character development (wants and needs), and moving the story forward (conventions and obligatory scenes).

Clear, concise, and compelling dialogue is achievable the same way you write a great story — by starting out with a clear, concise, and compelling framework. A framework like the Story Grid can help give you objective measures of how well your story works so you can learn how to write dialogue that flows naturally from your character’s authentic voice.

Special thanks to Kim Kessler for reviewing this post and providing some great feedback.

References

- Robert McKee: Dialogue: The Art of Verbal Action for Page, Stage, and Screen

- James Scott Bell: How to Write Dazzling Dialogue

- Marcy Kennedy: A Busy Writer’s Guide to Dialogue

- Sammie Justesen: Dialogue for Writers

Infographic