The Story Grid covers a lot of ground. With a 344 page book, over 120 podcast episodes, and more than 100 articles, it’s a comprehensive resource on how to line up every element of your novel to craft a page-turning story that packs an emotional punch. But where do you start to try and absorb all that knowledge?

This is a primer on how the Story Grid matches up with 11 concepts and terms that most writers already know: genre, scenes, acts, narrative arc, theme, outline, plot, protagonist and antagonist, conflict, setting, outlines, and exposition. It’s also a jumping off point with links to resources to dive deeper into a specific topic.

1. Genre

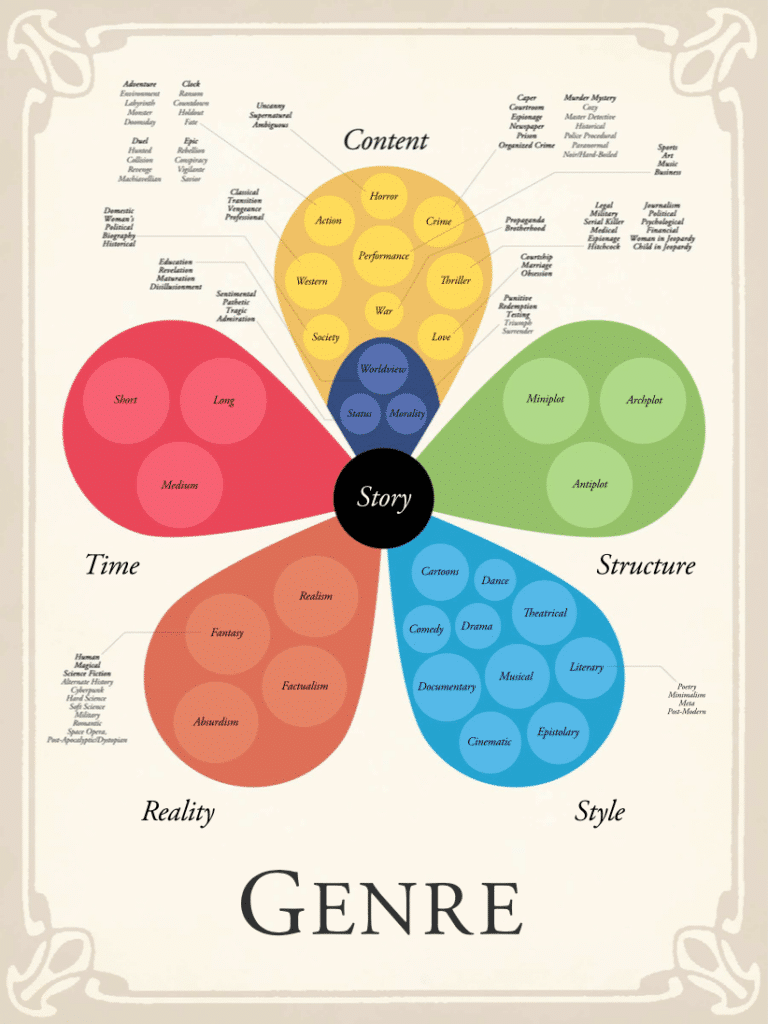

Genre is a method of categorizing stories that help set reader expectations for your book or screenplay. Getting genre wrong can lead to frustration and lost book sales. Getting genre right can be a boon to your career (and your bank account). The Story Grid splits genre into five leaves of a clover, each covering one aspect of a story – Time, Structure, Reality, Style, and Content. The Content leaf is the most useful in terms of constructing a story. It’s also what everyone talks about when they talk about genre. Let’s cover each leaf of the clover and then talk about how to find your genre.

First, the Time and Structure leaves. As a novelist, you’re in the Long category in the Time leaf. As for the Structure leaf, if you’re writing genre fiction, you’re probably writing Archplot. If you’re writing literary fiction, you’re probably writing Miniplot.

Next the Reality and Style leaves. In the Reality leaf, stories are categorized based on how much the audience will need to suspend their disbelief. The genres range from historically accurate biographies to fantasy or sci-fi that requires comprehensive suspension of disbelief. The Style leaf is about the sensibility and format of the story. Comedy versus drama. Literary prose versus musical versus epistolary (a.k.a. Made up diaries and letters) The Reality and Style leaves are useful in determining the sales categories to list your book on Amazon, but they don’t tell you as much about how your story should be structured.

The Content leaf contains the genres that do help you structure your story. Each of the 12 content genres – Action, Crime, Horror, Love, Morality, Performance, Status, Society, Thriller, War, Western, Worldview -is associated with a specific Core Value and narrative arc (see section below). Each Content genre also has a set of five to eight obligatory scenes and conventions that readers expect to find in your story. The first obligatory scene is the genre-specific Inciting Incident, which kicks off your global story. One of the last obligatory scenes in your story will be the genre-specific Core Event, which serves as the climax of the global story.

You can have more than one content genre, but one genre must be primary. See Story Grid Certified Editor and fiction author Valerie Francis’s in-depth article about genre and the impact finding her primary content genre had on her fiction career.

How do you find your primary content genre? Listen to Shawn help Tim sort out his primary content genre based on theme in this podcast episode or read Story Grid Certified Editors Anne Hawley and Leslie Watt’s advice on how to find your genre through the Core Event in this article.

2. Scenes

Scenes are the fundamental building block of a novel and learning how to write a compelling scene is the #1 job for a fiction writer.

In every scene, there must be change. A shift in life circumstances from beginning to end. From trapped to escaped. From alone to befriended. From overjoyed to grief. The way to create a shift in life circumstances is through a progression of events that obey the Five Commandments of Storytelling. Story Grid Certified Editor Rebecca Monterusso explains how the Commandments work in this article. You can also see how the Five Commandments apply to a specific story in this episode of The Author Copilot. Shawn and Story Grid Certified Editor and fiction author J. Thorn identify the Five Commandments in the Skittles commercial and mini-horror film Floor 9.5.

As a new novelist, your focus should first focus on learning to write scenes that show a clear shift in life circumstances and abide by the Five Commandments. This post can show you how to improve your scenes.

You can also listen to Shawn talk Tim threw examples of specific innovative scenes. A discussion of how Tarantino created a unique scene using a common scene trope – Stranger Knocks on a Door in Inglourious Basterds and an episode that includes a discussion of how Zero Dark Thirty and One Flew Over the Cuckoo’s Nest establish camaraderie (or lack thereof) in a surprising way.

3. Acts

You can think of the Story Grid as a 3-act structure where each act represents a shift in the Core Value either positively or negatively. A hero accepts their mission. Someone dies. The rebellion wins the big battle. Each act has a name. Act 1, or the Beginning Hook, is the first 25% of your story. Act 2, or the Middle Build, is the second 50% of your story. Act 3, or the Ending Payoff is the final 25% of your story.

The three acts must obey the Five Commandments of Storytelling and each contains one or more obligatory scenes which mark pivotal moments when the story shifts. The Climax of the third act tends to be the Core Event, the make it or break it moment for your protagonist, and the most important scene in your entire story.

There are some great podcast episodes where Shawn and Tim talk through examples of obligatory scenes from Thriller, Action, and Love stories. This episode discusses the Hero at the Mercy of the Villain (the Core Event of a Thriller) in Guardians of the Galaxy. This episode identifies the All Is Lost (a pivotal moment in the Middle Build for many genres) in Silence of the Lambs and Pride and Prejudice.

If you’d like to learn more about acts and get a rundown of all the obligatory scenes in a specific content genre, the Story Grid Editors Roundtable podcast can help. In each episode, five Story Grid Certified editors review a popular movie. They identify the content genre, obligatory scenes and conventions, and the events that make up the Beginning Hook, Middle Build, and Ending Payoff.

4. Narrative Arc

The narrative arc is what creates an emotional bond between your protagonist and your reader. You want to create a narrative arc that focuses on one Core Value that represents the wants and needs of your protagonist.

A Core Value defines the range of primal human needs relevant to your story. For example, Core Values might be Power to Impotence, Life to Death, Love to Hate, or Selfishness to Altruism. There’s a great explanation of Core Values in in this article by Story Grid Certified Editors Anne Hawley and Leslie Watts.

The Core Value is genre-specific. In Action stories, the Core Value is Survival. You’ll have multiple scenes where your protagonist is in mortal danger. The entire story revolves around the question: Will the protagonist survive this ordeal?

When a writer is clear on the Core Value, they don’t need a super-complicated plot. Readers intuitively sense the arc and are primed for the big, dramatic moments. When a writer isn’t clear on the Core Value, they often add plot points that confuse the story and make it harder to empathize with the characters. You know, like that feeling you had when watching Guardians of the Galaxy Vol. 2?

5. Theme

In Story Grid, the theme is called the Controlling Idea. The Controlling Idea is a single sentence that says how the Core Value changes and why the Core Value changes from beginning to end.

Here’s the Controlling Idea of The Firm, according to Shawn (p. 138 in The Story Grid: What Good Editors Know):

“Justice prevails when an everyman victim is more clever than the criminals.”

Story Grid Certified Editor Courtney Harrell wrote a great article about finding your theme by looking at yourself. Courtney also created a cheat sheet that lists the basic form of the Controlling Idea for each of the 12 content genres. This cheat sheet can help you make decisions about your story.

For example, let’s say you were planning to write a Thriller, but find that you’ve got a theme about respect and shame, which is associated with Performance stories. Now you know you’ve got a decision to make. What kind of a story do you want to tell? Do you want to tell a Performance story and focus on the respect and change theme? Or do you want to find a new theme that’s more appropriate to a Thriller?

6. Outline

Story Grid has two outlining tools: the Story Spine and the Foolscap Global Story Grid. The Story Spine is a three sentence outline that can provide direction when you’re working on your first draft, but still leaves plenty of room for your story to develop organically. The Foolscap is a more detailed method that works best after you’ve completed a Professional First Draft and you’re ready to edit.

The Story Spine explains the major events that lead to the Core Value shift across the novel. Each sentence of the Story Spine corresponds to an act. The first sentence describes the Beginning Hook. The second sentence describes the Middle Build. The third sentence describes the Ending Payoff.

Here’s a Story Spine for the popular crime novel and film The Firm.

A hotshot lawyer gets his first job.

The lawyer discovers his employers are criminals.

The lawyer outwits his employers and saves himself and his integrity.

You can listen to Shawn help Tim find the Story Spine for his first draft in this episode. You can also see more examples of Story Spines from popular stories in this post.

The Foolscap Global Story Grid is a one-page outline of your story. It gets all the important details about your global story – the genre, controlling idea, POV, obligatory scenes and conventions on one page. It also goes into greater detail than the Story Spine on what happens within each act. Shawn explains the Foolscap in this video. You can see his Foolscap for the Silence of the Lambs in this post.

https://youtube.com/watch?v=Njx9Bee4po4

7. Plot

A good plot is like a 100,000 word sudoku puzzle. It’s a unique solution to a logic problem that fulfills these criteria.

- Focused on a shift in Core Value from start to finish of the novel.

- Includes all the obligatory scenes of the primary content genre.

- Involves characters making choices that become more and more irreversible over the course of the story. The consequences of those choices escalate in terms of the number of characters affected (from a single person to the whole of humanity) or escalate in terms of the personal relevance of characters affected (from a stranger being attacked to the protagonist herself or the loved one of a protagonist being held hostage), or both.

- Comprised of scenes with clear changes in life circumstances for the characters that vary in type, they don’t repeat (For example, repetition would be three scenes in a row where the protagonist loses something important. First a job, then the dog dies, and then their romantic partner leaves them.)

- Comprised of sequences with clear changes in life circumstance that represent bigger life changes than what happens in scenes and that vary and don’t repeat.

- Comprised of acts with clear changes in life circumstances that represent larger changes than in individual sequences and that reflect the Core Value from the primary content genre. The amount of change for an act is larger than the change for an individual sequence and acts must vary and not repeat.

If that sounds complex, that’s because it is. It’s nearly impossible to land upon a story structure that works by intuition alone. You need to use logic to craft a compelling long-form story. It’s also a long-shot to plot out every beat and create a surprising story. You need to leave room for organic discovery.

The best stories come from writing yourself into a corner that it takes days or weeks to escape. If you want to surprise readers, first you need to surprise yourself. Working with the Story Grid Certified Editor can help you find the structure and plot for your novel.

8. Antagonist and Protagonist

Readers come to your story because they want to see your protagonist stressed and forced to change. Which means that if you want your protagonist to seem truly amazing, you’ve got to place them up against a seemingly unbeatable antagonist. A powerful villain creates an incredible challenge that forces the protagonist to grow in response and helps create meaningful change in the Core Value as discussed in this episode.

The villain is also the driving force of the action. They are the root cause of the Inciting Incident in Action and Thriller stories and whatever the genre, the force of antagonism owns the Middle Build. You can hear more about how villains drive action in this episode and learn more about crafting villains in this article by Valerie Francis.

So what then is the function of the protagonist? Your protagonist is the character who changes the most. They are the character who experiences the biggest shift in Core Value. They’re frequently also the point of view character. And the protagonist is the one who must face down the villain or force of antagonism in the big event.

9. Conflict

If all of your characters get what they want, you don’t have a story. Conflict is essential. It operates at every unit of story, and over the course of the story the consequences of this conflict become more and more serious and irreversible.

There are three levels of conflict: internal, personal, and extrapersonal. Internal conflict happens inside your protagonist. It’s the inner moral dilemmas that your characters face. Personal conflict happens between characters. It’s the conflict that happens in a relationship when each character wants a different outcome. Extrapersonal conflict is what happens between your protagonist and larger societal or environmental forces. It can stem from natural disasters such as hurricanes and earthquakes to man-made trouble such as societal norms, a corrupt government, or an overzealous judicial system.

In Action, Horror, Thriller, and Western stories there are specialized conflict roles –hero, victim, villain– that characters will need to play. Hero, victim, villain has been a popular topic on the podcast. This episode is the first time Shawn brings it up and it includes information about the psychology behind the concept. In stories with a hero, victim, and villain, at least one character must be playing each role at all times. One character can play multiple roles. For example, Nick Dunne in Gone Girl, plays the victim, villain, and hero and which roles he’s playing shift at key points in the story. You can also have multiple characters who play a role. This episode includes a discussion of how the Raiders of the Lost Ark uses a three-headed villain.

To make the most of conflict, you want to mix up the levels of conflict that you use in each scene. This episode contains Shawn’s advice to Tim on how to mix up his levels and how to set up a character for a potential betrayal.

10. Setting

What elements do you need to consider when crafting your setting and how do you create a fictional world that resonates with your readers?

According to Shawn, there are four dimensions of setting. The first dimension is Period, where your story takes place in time. Is it historical, contemporary, or future? Or is time irrelevant, as in George Orwell’s Animal Farm and Richard Adam’s Watership Down.

The second dimension of setting is Duration. What length of time passes for the characters from beginning to end of the story? Are you covering years, months, or hours over the course of the novel? Knowing the amount of time that the entire story takes will help you decide how much time to cover in smaller units of story.

The third dimension is Location. This includes the geography, the place on a map, as well as the physical environment. The buildings characters visit. The rooms where action takes place.

The fourth dimension of setting is the levels of conflict: internal, personal, extrapersonal. A story can include one, two, or all three.

What creates a fictional world that resonates with readers is that it feels familiar, but different. Shawn recommends using history to help inform your world. For example, this episode includes a discussion of how Tim could use historical coal miners as a source for his character’s slang and this one a discussion of how Tim could use the Green Berets, Navy Seals, or the interview process at places like Google to help create his training sequences.

11. Exposition

When you create your fictional world, there are rules of the world, character backstory, and historical record that you might want to share with your readers. This goes double for anyone writing historical fiction, fantasy, or sci-fi. Exposition is the name for those details you want to relate to your readers. Story Grid doesn’t have a different definition of exposition, but it does have advice on how to weave it into your story in a way that advances your story and entertains your readers.

Exposition can also be called “shoe leather”, “backstory”, or an “infodump”. Scenes whose only purpose are to share exposition should either be cut or reimagined. You can listen to Shawn’s explanation of why a life value shift from uninformed to informed is boring in this episode. That episode also includes a breakdown of how the TV show Mad Men created a scene that explained the advertising business, but still kept viewers engaged in the story. The secret? The subtext. Leslie Watts and Anne Hawley’s post about Essential Action can also help you find more ways to add subtext to your writing and keep your readers engaged.

Conclusion

What do you think of these explanations? Do they help you wrap your head around how the Story Grid can help your writing? Are there writing terms I missed that you’d like translated into Story Grid language? I’d love to hear your feedback in the comments.