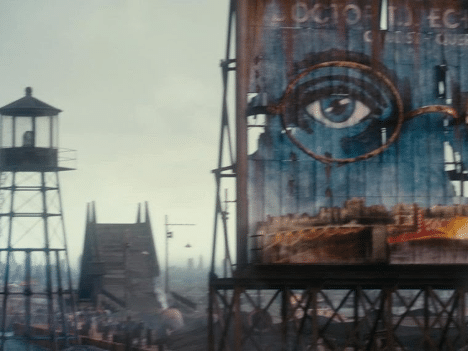

This week, Leslie looks at The Great Gatsby as part of her ongoing study of POV and Narrative Device. The novel by F. Scott Fitzgerald published in 1925 has been adapted multiple times. Today, in addition to the novel, we reference the 2013 film directed by Baz Luhrmann from a screenplay by Luhrmann and Craig Pearce.

The Beginning Hook, Middle Build, and Ending Payoff here describe the events of the novel.

The Story

-

- Beginning Hook – “Inclined to reserve all judgments,” Nick Carraway moves to New York City from the Midwest, where he learns his cousin Daisy’s marriage to Tom Buchanan is not a happy one and hears rumors of the mysterious man who lives in the mansion next to his bungalow, but when Tom takes him to a party in the city where Tom meets his mistress Myrtle, Nick must decide whether to reserve judgment and participate or not. He tries to leave, but gets sucked back into the party and stays all night.

- Middle Build – Nick is invited to a party at Gatsby’s mansion, and soon Nick arranges a meeting between Daisy and Gatsby, but when Tom discovers their relationship, Gatsby must decide whether to continue to pursue Daisy or walk away. Believing that Daisy has always loved him (not Tom), he travels with the group to the Plaza Hotel where Daisy won’t deny that she loves her husband.

- Ending Payoff – On the way back to the Buchanan household from the Plaza Hotel, Daisy drives Gatsby’s car and hits and kills Myrtle, and Gatsby decides to take responsibility, but when Nick tries to tell Gatsby the truth about Daisy and Tom, Gatsby must decide whether to believe in Daisy’s love or not. He waits at his mansion for her to call, where Myrtle’s husband arrives to shoot him before turning the gun on himself. Nick is the only one who mourns Gatsby’s death.

Genre: Worldview-Disillusionment with Obsession Love Story

Leslie: While I chose this story to explore point of view and narrative device, one question I have wondered about is, why The Great Gatsby has endured? Why is this considered “the great American novel,” and why does it still resonate? It’s a story that works by almost any critic’s or editor’s definition, and it’s beautifully written, but we can say that about loads of other stories. Americans like happy endings, and this story does not meet that standard. I think we appreciate it because it reveals a truth about this country that feels particularly relevant now, almost one hundred years after publication.

On a certain level, everything about The Great Gatsby communicates Status. Nick Carraway draws our attention to people’s pedigrees and surnames, their homes and where they attend college, their manners, posture, accents, and clothing. (All of this is relevant to POV and Narrative Device, of course.) Given this focus, you might conclude this is a Status-Tragic story for Gatsby, and you certainly could use the same events to tell the story of Gatsby’s rise and fall through that lens. But in the same way that The Godfather is not a Crime Story, I see The Great Gatsby is not a Status Story. It’s about Disillusionment with the American dream in the form of a reckoning of accounts.

At the beginning of the story, Gatsby and Nick both hold a naive, blind belief that the world is a certain way. Gatsby believes that if he works hard enough and amasses enough wealth, he can win Daisy because she truly loves him. Nick is inclined to think well of all people. By the end of the story, they both come to see a darker truth that the other characters around them already understand and have metabolized in their own ways.

Fitzgerald seems to be showing us that the American dream is only a license to pursue something better, though that’s not how people usually talk about it. The setting or domain of the story, which sets up the primary conflict, is characterized by large gaps in social class that create promise and optimism that give rise to the primary change that happens over the course of the story, not one of failure to success, but of blind faith to justified belief and ultimately disillusionment.

The Great Gatsby shows us how the Worldview-Disillusionment protagonist is different from the Worldview-Maturation protagonist: Both characters discover the way they viewed the world is wrong and both experience loss, but the Maturation protagonist attains gains agency, the ability to choose better goals, possibly because they have a supportive mentor and therefore accept the hard truth sooner.

The Principle – Point of View and Narrative Device

I’m looking at POV and narrative device, the subject of the third of the Editor’s Six Core Questions, in the context of The Great Gatsby. Specifically, I want to focus on the effects created by POV and narrative device choices.

If genre is what your story is about, POV and narrative device are how you deliver the story to your reader. POV tells you whether your story is written in first or third person, for example, and whether it’s written in past or present tense, but the narrative device or situation reveals who is telling the story, to whom, when and where, in what form, and why.

You write the story for your reader, but it’s so useful to consider the narrative device or situation, whether you reveal this to the reader or not, because these decisions create constraints that help you solve problems and make choices for your story. A specific narrative situation makes your life easier because it creates a specific purpose for the communication. When you know who’s speaking, to whom, and why, you have a lot of valuable information.

My bite size episode on choosing your POV can be found here, and you can find my article on narrative device here, and the article on POV here.

The Opportunity Presented by the Premise

In previous episodes, I’ve talked about the problem presented by the premise and other story elements. As an editor, I focus on diagnosing and solving problems, but I also help writers fulfill the promise of their story ideas. Being able to see both the promise and the challenges are valuable viewpoints. Thanks to a conversation with fellow Story Grid editor Mark McGinn, I’m reframing my inquiry as the opportunity now because I want to help writers focus on the possibilities in their stories.

Jay Gatsby is an ambitious young man in early 1920s New York City who wants to reconnect with and marry a former love who is from an entirely different social class and who is married someone of her class.

The global genre is Worldview-Disillusionment, so we’re seeing the protagonist (and in this case the narrator as well) come to realize that what he believed about people and the world isn’t true.

Because the protagonist must realize a dark truth, we’ll want a narrative device that allows different subjective perspectives on the same objective facts. We need a narrator who can navigate different levels of society and who is open-minded enough to withhold judgment.

Let’s look at how F. Scott Fitzgerald leveraged the opportunities within this setup.

What’s the POV?

Fitzgerald uses first person, what Norman Friedman calls “I as witness.” Nick acts as an observer of the events, though he’s also a participant. What I especially like about this example of first person narration is that it has the feel of an omniscient narrator and shows the range of this POV choice. The “omniscient feel” comes from the rich details that Nick shares and his perspecitive. He notices the way the other characters appear and what they say and do that reveal things they might not realize.

What’s the Narrative Device?

Who tells the story? Nick Carraway

To whom? The film shows Nick writing as part of treatment or recovery, but the novel doesn’t reveal his audience or purpose explicitly.

In what form? Nick explicitly refers to the written form. Metaphorically, it feels like the reckoning of accounts.

Where/when? Nick tells us he’s writing two years after Jay Gatsby’s death. He’s gained some perspective, and as a result, he appears as two different characters: the character who participates in the events and the narrator with greater perspective who knows how it turns out.

Because Nick tells us how things turn out in the opening of the novel and film, Fitzgerald employs dramatic irony as the primary form of narrative drive. In this form, we read on not to find out what happens but to learn how it happens and out of concern for the character(s). This is a good choice for a story with a negative ending because a satisfying ending is both surprising and inevitable. If you surprise your reader with a negative ending that was not telegraphed in some way from the start, you risk alienating them.

Why tell the story? What’s the Controlling Idea? I’ve found that the narrator’s purpose is often tied to the controlling idea or theme. Here I’ve identified the controlling idea this way:

We succumb to disillusionment when we learn a shocking, dark truth that we cannot yet metabolize.

This seems to be the result of Nick’s inquiry because he and Gatsby do not realize the truth in time, and neither possesses the ability to metabolize it.

How well does it work?

How well do POV and narrative device choices leverage the opportunity presented by the premise?

It’s hard to imagine The Great Gatsby told any other way. Just as Gatsby finds with Daisy, he may not be his own best spokesperson to present a case to the reader. Nick makes the case for him, and we immediately attach to Nick because he’s quickly established as a good guy with good intentions and an open mind. So even though his view of the world is not accurate, we accept his moral judgment of the situation, in part because he owns his lack of sophistication. In this way, Fitzgerald uses to great effect the need to telegraph a negative ending and use dramatic irony.

Valerie– The Middle Build in Two Parts

This week I’m continuing my study of the middle build of a story. Those of you who’ve been around the Story Grid Universe a while will have heard us talk about the 15 Core Scenes of the Story Spine. Getting those right is vital to the success of a story. However, often writers get lost in the middle build because it’s half the story and there’s a lot of ground to cover between the inciting incident of Act 2 and the turning point. So recently, in Action Story: The Primal Genre, Shawn outlined a way to break that huge middle build into two parts. Following this method, there will be 20 Core Scenes rather than 15. Of course, the 15 Core Scenes are still valid, and if you’re using the Story Grid method as a planning tool, I think it’s best to start with the 15 Core Scenes and then add the remaining five scenes when you have a better handle on what your story will be. When we’re planning, we want to work from the macro to the micro.

The beginning hook is the protagonist’s ordinary world and the ending payoff is the protagonist’s new-and-improved version of himself. What we want to examine then, is what happens during that middle build to arc the character? How does our hero change from the person he used to be, to the person he becomes?

The middle build is the extraordinary world. It’s an unknown environment for the protagonist, so he’s essentially a fish out of water. He doesn’t know who anyone is, or how anything works. By contrast, the antagonist is right at home. He knows how everything works and he has home court advantage. This is why we say that the middle build belongs to the antagonist. He knows stuff the protagonist doesn’t know. He’s got the upper hand.

Middle Build One: Middle Build One is the calm before the storm. The protagonist is trying to navigate this strange new world the best he can. He has the knowledge, skills, tools, beliefs and perspectives that he brought with him from his ordinary world. Little by little, he discovers that they don’t work here and his situation is getting worse. The tension builds until the story hits the midpoint climax, also called the midpoint shift or point of no return.

As you’d expect, this part of the story contains the Five Commandments of Storytelling.

MB1 Inciting Incident: The protagonist is taken into the extraordinary world by a threshold guardian and it’s clear that this is a whole new world. The hero approaches this alien environment as though he were in his ordinary world, and of course it doesn’t work. In Gatsby, this is when Tom brings Nick into New York city to party with Myrtle and the others. Nick doesn’t want to be there. He’d previously been drunk only once in his life and he politely refuses to stay and party with them. He says that Daisy is his cousin and that he doesn’t feel comfortable, but he soon comes around.

MB1 Turning Point Progressive Complication: Here the protagonist must try to outmaneuver the antagonist, and whether he’s successful or not, the antagonist gets a glimpse of the protagonist’s gift. Here, Gatsby wants Nick to invite Daisy for tea. It seems like a fairly simple request but it isn’t and almost instinctively, Nick knows it, which is why the request gives rise to a crisis.

We’re used to seeing the villain wanting to destroy the hero, right? That was certainly the case with Baby Driver. But Gatsby doesn’t want to destroy Nick, he wants to use him; he wants to manipulate him into doing his bidding. Gatsby tries to corrupt Nick with the offer of a “side job”. When Nick refuses, stating that this is a favour and he’s happy to do it, he reveals that he’s a nice guy. Being a nice guy and wanting to help people out, is his gift. Of course, this ties into the point of view; remember, Nick is the narrator of the story too.

When the antagonist glimpses the protagonist’s gift, something interesting happens. Keep in mind that the villain is the hero of his own story. So, like the protagonist of the global story, he is constantly evaluating those around him to determine who his allies are and who his enemies are. In this scene Gatsby is evaluating Nick. He’s testing him to see if Nick is a threat that must be destroyed, or if he can be manipulated. The offer of the side job is a test to see what Nick is really made of. Gatsby sees this “nice-guy” gift and decides he can use it to his advantage, and of course he does exactly that for the rest of the film.

MB1 Crisis: This is obviously the question that arises as a result of the turning point. Will the hero comply with the villain’s request, or defy it? As I said, the antagonist is evaluating the protagonist to see if he’s a friend or foe. So the way the protagonist answers this crisis question is pivotal to the story. We often see the hero defy the villain. That gives them, and us, a gauge for how formidable the clash between them will be. It sets up the core event of the story. In Gatsby however, we see Nick complying with his antagonist. This also sets up the core event and leads to Nick’s disillusionment, but in a way that gives Nick a false sense of security. Nick seems blissfully unaware that he’s being manipulated.

MB1 Climax: In the climax of MB1, the antagonist asserts his power. In Baby Driver, this is when Bats shoots the corrupt cops and ultimately blows up the market. It’s an over-the-top reaction to the situation. Gatsby demonstrates his power quite differently. He redecorates Nick’s cottage inside and out, in order to make it acceptable for Daisy’s visit. It’s also an over-the-top reaction. It’s a display of Gatsby’s wealth and power. He can get people to do his bidding, and he can make things happen fast! Whereas Baby became very cautious around Bats (only speaking up when Debora was threatened), Nick puts up no resistance whatsoever. In fact, when Gatsby has a moment of hesitation, Nick steps in to help. He’s Gatsby’s friend; he’s a nice guy.

MB1 Resolution: The resolution of MB1 is quite long. It’s the whole montage sequence of Gatsby, Daisy and Nick frolicking in the summer sun. It ends, as expected, with the midpoint shift which is when Nick realizes that Gatsby wants more.

The midpoint shift, which is also called the midpoint climax or the point of no return, marks the hero’s fall into chaos. Notice that Gatsby ropes Nick into his plan early and keeps him involved until the bitter end. Whenever he wants to spend time with Daisy, he invites Nick along too. Now, part of this is social convention, part of it is a cover story (Tom thinks Daisy is simply spending time with her cousin), but mostly—from a storytelling point of view—this is the antagonist’s way of making sure the protagonist is in it up to his neck. Nick is culpable.

Middle Build Two: The first part of the middle build is the calm before the storm, and this second part is the storm itself. It’s chaos. The protagonist has no idea what to do and is making it up as he goes along. When the protagonist is disoriented, everyone is disoriented. When the protagonist falls into chaos, all the characters fall into chaos. As with MB1, MB2 also contains the Five Commandments of Storytelling.

MB2 Inciting Incident: As I said a minute ago, the switch from MB1 to MB2 happens at the midpoint shift which is when Nick realizes Gatsby wants more. Here at the inciting incident of MB2, we get an event that is unexpected by both the protagonist and the antagonist. And, it requires them both to respond to that event in ways that counterbalance one another. The inciting event of MB2 is when Nick discovers that Daisy and Gatsby want to run away together. Gatsby is trying to convince Daisy to tell Tom that she never loved him. Daisy resists because, although she wants to be with him, she doesn’t want to go through the actual process of leaving her husband. She seems to want to magically blink and have the whole sordid affair resolved in a way that doesn’t hurt anyone and doesn’t shame her publicly.

Nick never expected that his agreement to invite her to tea would lead to this. Gatsby never expected that Daisy would refuse to leave Tom.

MB2 Turning Point Progressive Complication: Finally, here at the TPPC of MB2, the protagonist begins to see the extraordinary world for what it is. To this point, Nick had been dazzled by the wealth and carefree party lifestyle on Long Island. But now, he’s noticing the reality of what this lifestyle is. As a result, he begins to behave in ways that are counter to his pre-programmed behaviour/the way he acted in his ordinary world. Remember, he entered the extraordinary world armed only with the skills and knowledge he had in the ordinary world. He was a bright-eyed, bushy-tailed nice guy.

When Gatsby says that Daisy wants him, and Jordan Baker, over to lunch Nick is unimpressed. This is “the lunch” when Daisy will finally tell Tom, in front of everyone, that she never loved him and that she wants to run away to be with Gatsby. Whereas Nick accepted the original invite to dine with Daisy with a joyful buoyancy, how he’s filled with dread.

This invitation leads to their trip to the city which is when the global crisis happens.

MB2 Crisis: The MB2 crisis is the global crisis, but it’s actually Daisy’s rather than Nick’s. The entire scene is all about whether Daisy will finally leave Tom, or not. Nick is obviously implicated here. After all, he’s the one who made it possible for them to meet in the first place. For Nick, there’s the question of whether he’ll intervene in the argument unfolding between Gatsby, Daisy and Tom, or not. Earlier in the story he’d chosen to get involved. Here, he chooses to stay out of it.

MB2 Climax: The climax is when Myrtle is killed and Tom denies knowing her. He allows all the blame to be placed on Gatsby. The irony here is that with respect to Myrtle, Gatsby is entirely innocent.

MB2 Resolution: Finally, we have the resolution of MB2. Typically, this is when the protagonist prepares to fight the antagonist. He’s climbed out of chaos, seized the sword and is preparing for battle. Nick’s approach is to walk away from them all. He sees the extraordinary world, and the people in it, for what and why they are and has decided he wants none of it. He won’t even wait inside Daisy’s house for the cab.

Ok, so that’s a heck of a lot of information to take in. What I find most interesting here is that even though Shawn articulated these ten scenes specifically for the Action genre, it’s entirely possible to extrapolate them out into other genres. It’s also interesting to see how the story unfolds when the protagonist decides to go along with the antagonist rather than trying to combat him.

Kim– Core Event for Worldview-Disillusionment

This week’s story is a sad one, to be sure. Pretty heartbreaking. I was telling my husband about it and he said, “That’s the saddest movie and I never even watched it.”

So this season I am studying Core Events, to better understand how to execute the big payoff of a story (which will help me better understand how to begin with intention, and all the important stops to make along the way). The entirety of a story will make most sense in the context of its Core Event – this is the core moment of change in global life values, where the height of the core emotion is evoked and the reader’s expectations are paid off. All roads lead to the Core Event.

The Great Gatsby is a global Worldview-Disillusionment story. Here are some quotes from Shawn about this genre from The Story Grid book:

Remember that the disillusionment plot is a movement from a positive belief in the order of the universe, basic fairness etc. (positive) to a darker point of view, one that recognizes the murkiness of life, the real injustice and mendacity that plagues us all.

The disillusioned come to the conclusion that there is no treasure at the end of the hard-work rainbow, because there really isn’t any rainbow to begin with. What we think we want and how we think we can get there is never what it really turns out to be.

The value at stake in the Disillusionment plot is the lead character’s worldview. Generally, the progression of negativity of the [Worldview] value moves from ILLUSION to CONFUSION to DISILLUSION to the negation of the negation DYSTHYMIA (a chronic state of negative/ depression).

For Silence of the Lambs, Shawn adjusted the life values to be Blind Belief to Justified Belief to Doubt to Disillusionment. And I think that in itself is a valuable lesson — you can customize your Life Values to make them more clear and relevant to your story.

For The Great Gatsby, Illusion to Confusion to Disillusion makes sense to me, and in the film version at least Nick seems to fall into Dysthymia which is why he ends up in the sanitorium and eventually writing the book. So we see him at the negation of the negation and then jump back to the beginning where he views the people around him through an illusion of goodwill. So let’s look at the Core Event for when the life values ultimately shift from Confusion to Disillusionment.

In the film version, the core event moment of Nick’s disillusionment seems to come when Nick phones Daisy to tell her Gatsby’s funeral is tomorrow. Despite everything that has happened he still believes that they are decent, that Daisy loves Gatsby, and that they will do the right thing. He is told by the butler that they have left town.

“Please. I know that she would want to be there. If you would just get a message to her. Let me talk to her, please. Please.”

Note that he says please three times.

But he is given no further information. Left no address or way to contact her. Just gone without a word, and without acknowledging the man who loved her, who was killed because he protected her. Gatsby was blamed for the affair with Myrtle and her death and the two people who knew the truth couldn’t be bothered to pay their respects at his funeral. This active dismissal prompts Nick to have a revelation about their character:

Voiceover:

They were careless people, Tom and Daisy–they smashed up things and creatures and then retreated back into their money and their vast carelessness.

Immediately after this, we see Nick lose his temper for the first time. He yells at reporters in the house who are taking photos of Gatsby in the casket.

“Hey. Go on. Get out of here. Get the hell out of here!”

No please. His expression in the scene is similar to Gatsby’s expression earlier Tom had insulted his origins, one that Nick referred to as though “Gatsby had killed a man.”

His disillusionment is compounded in the resolution of the scene.

Voiceover:

“I rang, I wrote, I implored. But not a single one of the sparkling hundreds that had enjoyed his hospitality attended the funeral. And from Daisy, not even a flower. I was all he had. The only one who cared.”

Contrast this with the opening voiceover:

“In my younger and more vulnerable years my father gave me some advice. “Always try to see the best in people,” he would say. As a consequence, I’m inclined to reserve all judgments. But even I have a limit.”

So throughout the story, there is this undercurrent of waiting to see what sends Nick Carraway to his limit, where he can no longer reserve his judgment and is filled with disgust for the actions of others. The promise made in the beginning has been fulfilled.

This moment in the film is clear and defining. In the novel, the core event is executed a bit differently but still related to no one attending Gatsby’s funeral.

A little before three the Lutheran minister arrived from Flushing and I began to look involuntarily out the windows for other cars. So did Gatsby’s father. And as the time passed and the servants came in and stood waiting in the hall, his eyes began to blink anxiously and he spoke of the rain in a worried uncertain way. The minister glanced several times at his watch so I took him aside and asked him to wait for half an hour. But it wasn’t any use. Nobody came.

About five o’clock our procession of three cars reached the cemetery and stopped in a thick drizzle beside the gate–first a motor hearse, horribly black and wet, then Mr. Gatz and the minister and I in the limousine, and, a little later, four or five servants and the postman from West Egg in Gatsby’s station wagon, all wet to the skin. As we started through the gate into the cemetery I heard a car stop and then the sound of someone splashing after us over the soggy ground. I looked around. It was the man with owl-eyed glasses whom I had found marvelling over Gatsby’s books in the library one night three months before.

I’d never seen him since then. I don’t know how he knew about the funeral or even his name. The rain poured down his thick glasses and he took them off and wiped them to see the protecting canvas unrolled from Gatsby’s grave.

I tried to think about Gatsby then for a moment but he was already too far away and I could only remember, without resentment, that Daisy hadn’t sent a message or a flower. Dimly I heard someone murmur “Blessed are the dead that the rain falls on,” and then the owl-eyed man said “Amen to that,” in a brave voice.

We straggled down quickly through the rain to the cars. Owl-Eyes spoke to me by the gate.

“I couldn’t get to the house,” he remarked.

“Neither could anybody else.”

“Go on!” He started. “Why, my God! they used to go there by the hundreds.”

He took off his glasses and wiped them again outside and in.

“The poor son-of-a-bitch,” he said.

I would also say that this moment is a kind of core event for the Love-Obsession story, a Failed Proof of Love scene from Daisy. She was unable to commit to Gatsby in life, and now she won’t honor him in death.

So this Core Event moment feels like the proverbial “straw that broke the camel’s back”. It’s as if Nick (like Gatsby) is holding out hope that people will prove themselves to be decent and respectable, only to be proved false, leaving him disillusioned about people, New York, the East …

The core emotion of a Worldview story that ends negative (Disillusionment and some Revelation stories) is loss and pity. All change comes with loss, and Disillusionment is one of those times when that is all it feels like, because as Leslie mentioned earlier, unlike Maturation, the protagonist doesn’t move through this loss into better suited goals. They stay mired in the loss.

In the resolution of the novel, there is a line that shows Nick’s pity for Tom …

I couldn’t forgive him or like him but I saw that what he had done was, to him, entirely justified. It was all very careless and confused. They were careless people, Tom and Daisy–they smashed up things and creatures and then retreated back into their money and their vast carelessness or whatever it was that kept them together, and let other people clean up the mess they had made. . . . I shook hands with him; it seemed silly not to, for I felt suddenly as though I were talking to a child.

So while Gatsby may be the main character the story is about, we experience the fullness of the Disillusionment arc through the POV character, Nick, after Gatsby’s death.

Final Thoughts and Takeaways for Writers

We like to round out our discussion with a few key takeaways for writers who want to level up their own writing craft.

Valerie: My key takeaway this week is that the protagonist doesn’t always have to actively combat the antagonist. The hero can choose to go along with the villain. It’s not an easy thing to pull off, and it certainly won’t work for every genre, but it’s an interesting artistic choice for a worldview disillusionment plot.

Kim: Something I want writers to remember is that whenever you have a global internal genre, it’s important to shift your thinking to external concrete specifics that you can use to demonstrate the life value shifts, especially in the Core Event. We want to ensure the reader feels that core emotion, which likely means they need more than just what’s going on inside the character’s head.

Leslie: Revisit the classics! Even if you read The Great Gatsby in high school and weren’t crazy about it, read it and others again. Much like Nick, you’re a different person than you were then, and you’ll have a different perspective. There’s plenty for us to learn from the way Fitzgerald executed this story. But don’t take my word for it, check it out for yourselves and keep your Story Grid goggles handy.

Listener Question

To wind up the episode, we take questions from our listeners. This week’s question comes to us from Melanie Hill in the Story Grid Guild forum.

How do the Roundtable team study sequences in existing works (or Masterworks)? How do you use or plan sequences with clients, and in your own writing?

Kim: I love this question and I love that you’re thinking about this. So just for clarity, sequences are one of the units of story that is larger than a scene. The units range, from largest to smallest: Global, subplot, act, sequence, scene, and beat.

A sequence is two or more scenes that together create a unit of change–they represent a larger unit of change than a scene. What I love about them is that they are another way to execute a life value change, and another way to look at building a unit of story. Whether you are trying to break down a masterwork to understand what makes something tick, or trying to write or revise your own novel, looking at sequences is really useful. It’s let you see big swath changes happening on your life value spectrum.

For myself, in the Beginning Hook, I usually like to think about it in three sequences. This is how I will map out and plan my own novels, and it’s something I observe fairly well in other stories. So if we imagine that the Beginning Hook is going to be fifteen scenes–based on Shawn’s educated recommendation in a sixty scene novel, where there are about fifteen scenes in the BH, 30 in the MB, and 15 in the EP), I like to think of them as three sequences of five scenes. So the first sequence (made of five scenes) is where I would set up my Status Quo, introduce my Inciting Incident, and probably my first Progressive Complication. Then the next sequence (the next five scenes) are going to have more Progressive Complications that lead up to the Turning Point Progressive Complication. And then in the last sequence (the final five scenes) we’re going to go through the Crisis, the Climax, and the Resolution of the BH.

Again this isn’t hard science, obviously, but this is something that I have witnessed and helps get my mind thinking. It also helps with pacing. Another thing that it helps me solve personally are those macro to micro problems. I can say, “Okay I have five scenes to get from the beginning of the book to my inciting incident or my first progressive complication. What do I need to accomplish in this scene that moves my protagonist forward?” I don’t have to move them all the way forward, I just have to move them one scene-worth forward. And then I have the next scene to do the next job.

When you can start looking at things in sequences and understanding “I have this much room to make this change happen” you can break it down into more micro elements like scenes and beats. This helps with pacing and problem solving and all kinds of stuff.

Also, the other thing I want to mention about sequences is that they work really well for plotters and pantsers. So for plotters like myself, we can use it as one of the ways that we plan and then get down into the nitty gritty details within it. For a pantser, you can use those 15 or 20 core scenes that Valerie was talking about and can plan a sequence to get you to that next core scene. You can say, “What is my next Core Scene? What scenes do I need to get me to that next Core Scene?” And then once you’re there ask yourself, “What scenes do I need to get me to the next Core Scene?” And so thinking in that way, in a sequence, between major Core Events, is a way that as a pantser to know a bit of what’s coming but also give you plenty of room to discover and explore on the page.

Join us next time when Kim will look at the Core Event for the Performance and Status genres in the 2000 dance film Center Stage. Why not give it a look during the week, and follow along with us?

Your Roundtable Story Grid Editors are Valerie Francis, Kim Kessler, and Leslie Watts.