Download the Math of Storytelling Infographic

Welcome to the Season Six preview episode of the Story Grid Editor Roundtable Podcast. This is a show dedicated to helping you become a better writer, following the Story Grid method developed by Shawn Coyne.

It’s currently autumn here in the northern hemisphere, which feels like the perfect time for us to kick off our next phase of in-depth study.

‘Tis the season to embrace change! Which, after all, is what stories are all about.

To kick things off, Jarie has a special announcement. He’s leaving the Roundtable to try something new. No official announcement yet, but he’ll focus on stories of the struggles one goes through to create something from nothing. Want to follow Jarie on his new journey? You can find him on Twitter @thedailymba or on his site, theDailyMBA.com.

Kim: Thank you so much, Jarie. We are so excited to see what you tackle next, and I can’t wait to read your love story memoir so if you’re looking for beta readers—hit me up!

Change is hard but we know it leads to growth.

It’s been two years, five seasons, 95 episodes, and 75 films. Holy macaroni! That feels good to say. We’ve learned so much about the craft of storytelling by studying films. It’s a great way to understand global structure. But because we’re always looking to level up our craft, this season we’re going deeper: to the page!

While we’ll continue to incorporate films in our studies, we’ll also analyze short stories, novels, and scenes from novels.

As always, this is an adult conversation and you may hear some adult words.

So we hope you’re ready to dive deep, because in Season Six we are going all in.

ANNE’S SELECTION

During Season Five I studied three novel-to-film adaptations, with a personal emphasis on reading the novels.

Two purposes:

- break away from our reliance on movies

- Figure out what novels are for

I had these questions:

- Why bother to write novels?

- Do novels still have a place? Who even still reads? (Consider this article and this one.)

- Can a story that begins and ends in words on a page do anything that a filmed or illustrated one can’t do better?

- If reading is on the decline–and it clearly is–then why bother writing for the quote-unquote printed page?

My conclusion is subjective and personal. I still think the written word is important and that reading a story is a wonderful experience. All three of my novel selections were better than their film adaptations, even when the film was really good (Beale Street).

The other day, I was at the Portland Book Festival, a big literary event. I called a Lyft to go home, and when the car pulled up, the driver had a copy of one of Robert Jordan’s Wheel of Time series on the front seat. I said, “Oh, Robert Jordan! I’m re-reading all those books in preparation for the TV series,” and we talked about the books all the way home. He said, “I hope what they do on the screen matches my own image of the characters and the world,” and we agreed that it probably wouldn’t. Nothing ever quite matches what you imagined when you read it.

I’m fascinated by that power of the written word.

I’m fascinated by the connections between Story Grid structural principles and line writing, too.

So for Season Six, I’m doubling down. I’m going to ask everyone to read. But I’ll make it as easy as possible: I’m going to look at short stories.

Short stories are a bit of a compromise. They probably won’t have the big three-act structure of a novel, but on the other hand, reading and analyzing one should take us no more time than a movie typically does every week. I hope some of our listeners will be inspired to return to reading, or branch out in their reading, and try something new. In keeping with that hope, I’ll choose stories that are readily available, and under 10,000 words.

I’ll announce all three titles in plenty of time for listeners to find and read them.

Short stories might not meet genre conventions quite the way we expect. They might tend to leave out a commandment here and there. They might be more like jokes, with a build to a punchline. That’s what I want to find out.

Story Grid is publishing a short story anthology very soon–Kim is one of the anthology’s editors–and I think we might need to start building a database of short stories and tools for writers who want to explore the form.

For everyone else’s episodes, I’ll be continuing my informal study of scene types, a tool that seems to be valid for all story forms.

My first story is “Wolves of Karelia” by Arna Bontemps Hemenway, published just a few months ago in the Atlantic Monthly. It’s a masterpiece of brevity–a life, a love, and a war in 5000 words–and we’ll analyze it in Episode 4, going live on January 8.

LESLIE’S SELECTION

In the last two seasons, I’ve focused on Action stories, and this season, I’m changing things up to focus on a technical topic: Narrative Device and Point of View.

POV and narrative device combined are a topic that I should have known would be a natural for me. In life generally, I’m fascinated by how things work. And POV and narrative device together are the tools you use to create a particular experience for your reader.

When you want to write or tell a story, you start with an idea that includes characters, events, settings, emotions, ideas, etc., a bunch of content that you want to share with someone else. You must do something with all that content in order to share it, and the business of transmitting what’s in your head to the head of someone else is what this topic is all about.

Again, narrative device and POV create the reader’s experience of your story.

In my recent bite size episode, I talk about how we can write the same basic story, including the same genre, characters, events, and sometimes even the same controlling idea, but end up with a vastly different reader experience, depending on the narrative device and POV we choose. That’s because the material is presented through the lens of the narrative device, which we translate into our POV choice.

Your narrative device tells you (1) who is telling the story, (2) to whom the narrator is telling the story, (3) where the narrator stands in relation to the events of the story, (4) when the narrator conveys the story in relation to the story’s events, (5) how the narrating entity conveys the story to the audience, and (5) why the narrator is conveying the story.

Ideally, your POV choice—first, third, omniscient—should make sense in light of and flow from your narrative device.

Again, the two decisions combined create your reader’s experience with structure, the scenes you include, the order in which you present them, and the words you use to convey them. So not only are these vital decisions, but once you make them, they can help you make loads of other decisions about your story. The more thoughtfully you consider these choices, the easier your life will be as you write and revise.

Since I’m in the business of helping writers write great stories, this feels like a worthy area of study. I’ll explore these elements in three films adapted from written material. I’ll also look at narrative device and POV in the stories my fellow Roundtablers choose. Movies can be useful for looking at narrative device, but not so much for translating that to POV and the decisions writers have to make on every page and in every sentence. Studying two different versions of the same or a similar story will also help us identify the experience created by the writer’s and filmmaker’s choices.

My first story is It’s a Wonderful Life, which is based on Philip Van Doren Stern’s short story “The Greatest Gift.”

I can’t wait to deepen my study of narrative device and POV and share what I discover in Season Six. It’s a Wonderful Life and “The Greatest Gift” will be featured in episode 1, and we’ll post it on December 18.

VALERIE’S SELECTION

If you’ve been listening to the podcast for any length of time, you’ll know that I’m writing a psychological thriller, and I’ve been using the stories here on the show as Masterworks for various storytelling principles. I’m making some good progress now and the book is starting to shape up (finally!). But there’s at least one major concept that I haven’t tackled yet and considering how crucial it is to telling a story that works, I thought it was time to sink my teeth into Forces of Antagonism.

Now, what do I mean by “Forces of Antagonism”? Some of them are obvious external villains, like Lex Luthor. But it goes way deeper and broader than that. Forces of Antagonism include opponents, foes, adversaries, enemies, minions, our inner demons, our shadow sides, the environment and so much more.

I’ve heard Shawn say that the middle build belongs to the villain. I’ve also heard that a story is only as good as its villain; after all, it’s the villain that gives the hero a chance to be heroic.

If that’s the case, if my novel is going to work, I’d better have a very good handle on who the villain is and how he (or she!) is going to keep my story moving.

I wrote a Fundamental Fridays post about Forces of Antagonism a while ago, and my key takeaway was that the Hero, Victim, and Villain roles are intrinsically linked. That means, to do this justice I’ll also have to examine the relationship between the antagonist, the protagonist and the victims.

This is a huge topic (one that needs an entire book to discuss), so I need to narrow my study down to those characters that are similar to the kind of villains I want to create. The first one is the shapeshifting villain; antagonists who take on multiple roles throughout a story. We saw this in Black Swan where mentors and allies were also forces of antagonism. I’m seeing this kind of villain a lot in psychological thrillers, and it makes sense because it adds to the protagonist’s mental confusion. How can characters, like Nina Sayer, know who to trust or what to believe if her mentors are also her enemies?

So, for my first pick this season, I chose the 2014 award-winning film, Whiplash, written by Damien Chazelle. I absolutely loathe the villian in this story, so I’m curious to find out how Chazelle managed to evoke such a strong emotional response in me.

That episode will air on New Year’s Day!

KIM’S SELECTION

For season six I am studying change—specifically the change in Life Values.

I am obsessed with Life Values because they are a representation of the Universal Human Needs that stories are all about and the foundation to understanding genre. Life Values unlock how the patterns of story structure actually function.

I began this study in Season Four by examining my favorite kinds of stories, Global Internal Genres, and then in Season Five, I looked at stories that don’t quite work.

At this point, I feel pretty confident with which life values to communicate to my audience in a given genre, and even when to communicate them across the story spine. But I am on a quest to unlock how to communicate these life values.

So many times a writer will intend to demonstrate something to their audience, but it gets lost in translation. Either the information never makes it to the page, or it is delivered in a way that doesn’t allow the audience to perceive it.

I want to zoom in on specific moments in the story and unpack what is happening and how we know, so that I can communicate the kinds of complex authentic human experiences that my heart aches to share.

So to kick this off, I am going to be looking at story Beginnings, starting with what I think is the most underrated part of a story: the status quo.

For me, this is an essential part of a story. It’s where the initial state life values are established. We are introduced to our protagonist, her world and specific situation. This is established to lead us to the first major event in the story: the inciting incident. By having a clear status quo, the life value shift that takes place in the inciting incident means more. There’s a clear before and after.

I want to look at these elements and see the principles and specific tactics at play so I can use them in my own original fiction. I am making the active effort to craft my own stories in 2020, and I can’t wait to apply what I learn and share it with you.

For my Season Six picks, we will be looking at books adapted to film. This is relevant for me because I craft stories through both prose and film. It’s extremely important to me to understand the different methods these mediums use to communicate Life Values.

For my picks, we will be watching the film and examining the first 10 percent of the book at the line level. I can’t wait to begin!

The first story I’ve decided to examine is The Guernsey Literary and Potato Peel Pie Society. You can download the free sample pages on Amazon, or better yet, read the whole book with me! The film version is available to watch on Netflix. The episode will air December 25.

So there you have it. The first four episodes of Season Six are coming your way. We hope you’ll dig in with us and challenge yourself in new ways as we all change and grow and continue to level up our storytelling craft.

Join us next week for Leslie’s wonderful look at point of view and narrative device in the context of It’s a Wonderful Life and “The Greatest Gift” by Philip Van Doren Stern. Why not give it a look or read and follow along with us?

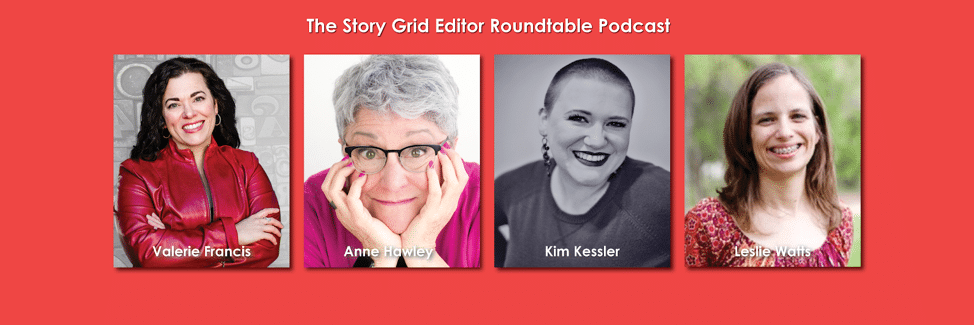

Your Roundtable Story Grid Editors are Valerie Francis, Anne Hawley, Kim Kessler, and Leslie Watts.

Download the Math of Storytelling Infographic

Share this Article:

🟢 Twitter — 🔵 Facebook — 🔴 Pinterest

Sign up below and we'll immediately send you a coupon code to get any Story Grid title - print, ebook or audiobook - for free.

(Browse all the Story Grid titles)