This week, Anne pitched If Beale Street Could Talk as a case study in adapting a literary novel to the screen. This critically-acclaimed 2018 film was directed by Barry Jenkins from a screenplay he adapted from James Baldwin’s 1973 novel of the same name.

The Story

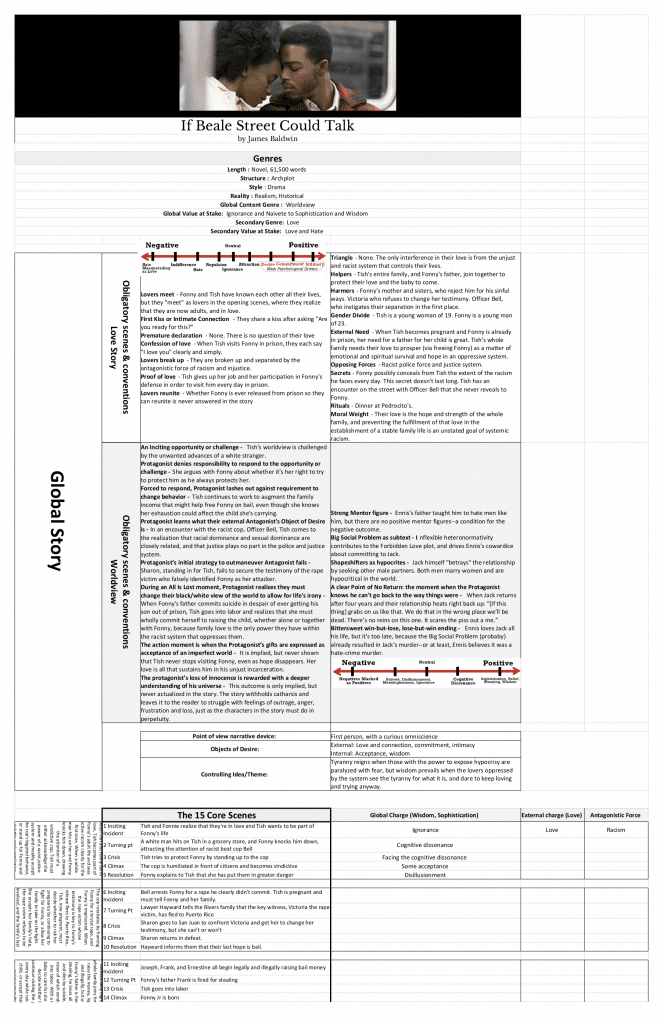

This is a complex, multi-layered, literary story that certainly looks like–and is billed as–a love story. It meets most of the obligatory scenes and conventions of a courtship story, some in a modified form.

As with many love stories, there’s an internal genre of Worldview. As with other love stories we’ve looked at where the lovers are prevented by outside forces from fulfilling their commitment to each other, there are strong Society elements at play.

What’s more, both the novel and the movie are told in a non-linear sequence, so your definition of the beginning hook, middle build, and ending payoff will change depending on how you read the sequence of events, and which genre you decide to follow.

For the sake of simplicity, I’ve decided to focus on Worldview Maturation as the global genre, and stack the story events up in linear time, rather than in the nonlinear order the novel and movie both employ.

Genre: The 15 core scenes from the protagonist’s point of view seem to turn more on the values of naivete and sophistication about racism and its negative effects on love between black people in 1973 New York, that Worldview genre is the one I tried to fit into this delineation.

Please keep in mind that this skeletal structure barely touches on many of the really powerful moments in the story. Jarie is covering several of them in the Love story shortly. Leslie will be looking at the story from a couple of other angles after that, and I know Kim will be making a strong case for the global genre of Society.

- Beginning Hook – When Tish and Fonny fall in love, Tish wants to become part of Fonny’s adult life in New York City, learning to see active racism clearly for the first time in a relatively sheltered life. When a white man hits on her and Fonny knocks him down, drawing the attention of a vindictive cop, Tish must either acknowledge the power of a racist justice system and meekly accept the cop’s bigoted behavior, or stand up for Fonny and risk the cop’s retaliation. She stands up to the cop, but Fonny tells her that she has helped put them both in danger.

- Middle Build – The cop retaliates by framing Fonny for a brutal rape, and Fonny is imprisoned. When the rape victim whose testimony is key to Fonny’s release flees to Puerto Rico, Tish, now pregnant, must decide whether to risk her pregnancy and health by continuing to fight for Fonny, or allow her family to take on the fight for her so she can offer her real gift: the love and hope she shares by visiting Fonny every day in prison. She accepts her family’s help, and her mother goes to Puerto Rico to confront the victim, but the traumatized woman refuses to be involved. The family’s last hope for Fonny’s release is bail.

- Ending Payoff – When bail is set unreasonably high, the whole family joins forces to raise the money, legally and illegally, but when Fonny’s father is fired for stealing, he loses all hope and dies by suicide, the news of which sends Tish into labor. With a new baby to care for she must decide whether to continue visiting the prison every day while raising a child, or accept that the racist system that incarcerated Fonny will never let him go. In the movie, she continues visiting him. In the book, this decision is not shown.

Scroll down for Anne’s Global Story Grid Foolscap for the story.

Anne – The Principle: The “Unadaptable Novel”

This season I’m looking at novel-to-film adaptations, trying to figure out what, if anything, novels can do that filmed stories can’t do–or don’t do well. Baldwin’s If Beale Street Could Talk has a lot to say on the subject.

First of all, if you’re interested in discovering this novel, I can enthusiastically recommend the audiobook version read by Bahni Turpen. The novel draws deeply on the particular voices of African Americans of the great migration, living in Harlem in the 1970s, where the parents’ generation still have a bit of the South in their voices. The Beale Street of the title isn’t in New York City, but in Memphis, Tennessee, the center of blues music in the early 20th century. I didn’t grow up around those voices, so hearing them read aloud not only was a pleasure, but really helped bring the first-person narrative and the dialogue to life.

Now, on to the question of how or whether the novel is better than the movie, and what I as a writer take away from that.

I want to start with this: we’re novelists and memoirists here on the podcast, and we’ve always aimed the show primarily at fellow novelists. When asked why we analyze movies instead of novels, our answer has been because movies are good vehicles for studying story structure in a convenient two-hour form.

But by always analyzing movies, we’ve tended to lose sight of the novel form itself, and tacitly reinforce the idea that a good story and an easy, comprehensible movie are exactly the same thing, a Venn diagram that’s a single circle.

My aim for some time has been to question that stance.

If Beale Street Could Talk is a very good movie by most measures. It was critically acclaimed, it was nominated for loads of major awards and won a lot of them, including one Oscar. It made back its cost plus a little more, it has a metacritic score of 87 and a 95% Fresh rating among professional film critics on Rotten Tomatoes.

The audience reaction was lower–75% or so–with most negative reviews centering on words like “slow,” “boring,” and “nothing happens,” clearly signaling that this movie just isn’t for everyone. Fair enough–and that’s what I want to look at.

All of us have thoughts on the show today about the extent to which the film works as a story. It takes takes huge swaths of text directly from the novel. It’s true to the novel in most ways, and Barry Jenkins has said in several interviews that he is devoted to Baldwin’s work, and wanted to be as faithful to it as possible, while still being a filmmaker. Here’s a quote from Doreen St. Félix, a film critic for the New Yorker:

In his breathtaking book-length essay on film, “The Devil Finds Work,” Baldwin acknowledges that the work of adaptation involves “doing considerable violence to the written word.” The violence was necessary, he writes, transformative like what goes on in a forge; transcendent filmmakers don’t shy away from the high temperatures of creation.

Barry Jenkins himself has pointed out that the novel might take 20 hours to read, while the film takes less than two to watch, and he says, “So where do those other 18 hours go?”

This is the fundamental question about adaptation. Jenkins talks about the “luxury” of a novel, where the author has all the time and space they need to go deeply into characters’ thoughts and feelings, and their own philosophies. Movies can’t do that. Even a long multi-part series on film can’t really do that, because the viewing audience won’t put up with it. That’s not what movies (or other filmed story forms) are for.

And that brings us to what I think novels may be for. Can a good novel be just a good movie in writing? Sure. There’s nothing wrong with writing a movie-novel, that is to say, a straightforward novel that would make a good popular movie.

There’s nothing wrong with following the Heroic Journey structure, with an archplot involving a central protagonist who has a clear arc. Whether you dream of being optioned for a movie, or just want to write a novel that is as smooth and effortless to read as a movie is to watch, here is some advice from the book Adaptation: Studying Film and Literature, by John Desmond and Peter Hawkes.

- Your novel will be under 300 pages or under 80,000 words, but over 15,000 words. Too long and a filmmaker would have to cut a lot of it. Too short, and they would have to make up stuff to fill in the time.

- If Beale Street Could Talk comes in at 297 pages, and just over 60,000 words, so we can tick that box.

- Your cinematic novel will be written in scenes, and will have the three-act structure of a beginning, a middle and an end, because that’s how movies are built, and that’s what readers of popular movie-like novels expect.

- Beale Street is written in two parts. The first is 90% of the book, the second is the remaining 10%. Its timeline is nonlinear, and its scenes, accordingly, aren’t clearly delineated. There are no chapter breaks, either. Scenes, such as they are, are long and conversational, and the movie adaptation, being faithful to the text, has some of the longest scenes I can recall in any recent movie. This results in some of those one-star user reviews about “long” and “boring.” (Important note: I don’t personally find it boring. I find it brilliant, and I loved it.)

- Your text will ideally not depend on your authorial voice or style to deliver its message, or on tone such as sarcasm or irony. That kind of strictly literary, textual stuff doesn’t translate to the screen.

- Baldwin’s novel is generally regarded as a masterpiece of authorial voice, stemming in part from his upbringing by a preacher. What’s more, to understand the novel, we must understand Baldwin’s tone of anger as well as his fierce love and sensuality.

- Your novel won’t lean heavily on literary allusions, philosophical ideas, or abstract meditations. None of that is story per se, and it’s unfilmable.

- Baldwin’s novel does only a little of this, and mostly it’s in the dialogue, so he gets another checkmark here.

- Symbolism, if any, will not lie at the heart of your story. Many great movies are rife with symbolism, provided it’s visual, but symbolism is lost on general audiences. If stripping it out would break your story, you’re not writing cinematically.

- There is quite a bit of symbolism in Beale Street, especially around Fonny’s sculpture, but the story doesn’t depend on it, so it gets a checkmark here, too.

- Your cinematic novel should not be written in the first person, or use a complex combination of points of view. The only way to work with that in film is the dreaded voiceover.

- Beale Street is written in the first person, and the POV isn’t simple. Tish’s perspective transcends what she could have witnessed or known about. Barry Jenkins’ film, accordingly, depends heavily on voiceover.

- And finally, your novel will not depend on detailed historical information to work. Apparently, movies that lay on too much historical realism tend to lose sight of the story.

- Beale Street was written almost 50 years ago, so it’s historical now, and the film version has been criticized for lingering too much on period wardrobe and set design. Go figure.

So there you go: besides the Story Grid basics of choosing a genre and sticking to it, if you want to write a novel that reads like an easy movie, follow those guidelines.

But what if you don’t, as James Baldwin clearly didn’t? Even though yes, Barry Jenkins made his novel into a fine movie without desecrating it by changing it too much, the movie was not exactly boffo box office. It was not–I’ll say again–for the mythical “everyone.”

What if you DO want to write longer than 300 pages? What if the story you want to tell arises from philosophical and political beliefs, or revolves around symbolism? What if you want to tell a story with multiple points of view or a complex, nonlinear structure, ot without traditional scene/chapter breaks? What if you like lyrical writing and a strong literary voice?

Well then, here’s my recommendation: try to break away from equating a good novel with a slick, easy movie. Novels can do more, and sometimes they should, because whatever they do have in common with movies, it’s probably safe to say that movies nowadays do those things better.

I think it’s up to some of us to go deep into characters’ thoughts, to take more time with our story, our language, our literary style; I think those of us who want to examine deep ideas through the medium of fiction should do exactly that.

Does this mean I think we should all jump ship and abandon sound story structure? No, of course not. But as I said last week about Jupiter Ascending, I’d rather aim for the moon and “miss” in terms of perfect delivery on the expectations of the mythical Everyreader, than tame my story ideas down to some template because I’m afraid to break rules.

If Beale Street Could Talk is a beautiful movie, but it’s an even better novel. Go read it and find out why.

Kim – Wonderful, Anne. I love this so much. I love the freedom this story showcases. And the power to tell the story that’s most important to you in the way that it needs to be told. The power of intent and knowing your own definition of success and how you measure it. It’s given me a lot to think about. Thank you.

Other Perspectives

Jarie – Pure Love Torn Apart

What I really loved about this movie is the way it reaches down your throat and grabs your heart right from the beginning. At no point does the story let off on the gas. You yearn to see Fonny and Tish together right away and this scene kicks it all off.

[Clip runs from 0:02:57 to 0:05:45 of the film and shows Tish visiting Fonny in prison and telling him, through the glass and over the phone, that she’s pregnant.]

This is one of the most masterful scenes about love and longing that I have ever witnessed. It’s also a wonderful intro scene for the theme of the movie, stated brilliantly by Tish, at the beginning. After this, we’re off to the races. Even the voiceover along with the dialogue just hits you in the solar plexus that you gasp for air, wincing in pain, waiting for the next punch to come. I’m tearing up just thinking about it.

This season, I’m looking at all our movies through the lens of love and how love stories can be used as an external genre for memoir. So, Anne, thanks for picking this film and book. I’m going to read it because it’s a master work in how to use a love story to give narrative drive to addressing big issues.

There are so many good scenes to pick from that it was hard to narrow down ones to look at. I do think this one about when Tish knows Fonny loves here is simply perfect.

It’s obvious from this scene that Tish is head over heels in love with Fonny and Fonny is as well. Although the acting is superb, listen to the dialogue.

Clip runs from 0:13:55 to 0:15:10 in the film and show Tish and Fonny walking through New York City, while Tish speaks the following voiceover:

TISH: The day I realized Fonny was in love with me, was strange. It was the day he gave my mother the sculpture. I dumped water on Fonny’s head and washed his back in the bath at the time that seemed so long ago. I don’t remember that we had any curiosity about each others bodies. Fonny loved me too much. And that meant that there had been no occasion for shame between us. Flesh of each others flesh. We took for granted that we never thought of each others flesh. And yet, it was no surprise to me when I finally understood that he was the most beautiful person I had seen in my entire life.

How does that make you feel?

For me, it encapsulates pure love in all its splendor. It’s a moving tribute to the purity and intimacy that all people yearn for.

These words set up the fall that is to come. The situation that our young lovers find themselves in is heartbreaking. It’s made worse by, which we find out later, the institutional, systematic racism that put Fonny in jail.

On top of that, the main hinderer to their love is Fonny’s mother, who is played masterfully and the dialogue encapsulates her perfectly as a God fearing mother who “prays everyday that her boy will be released from the dungeon that he is in.” Even though she is in only one scene, you feel her throughout the movie.

I can’t say enough about the fabulous dialogue and the tender scenes between Tish and Fonny. Those scenes, interwoven between the stark reality of the Fonny being in jail, raises the stakes by powers of 10. You feel for these two lovers that were torn apart. You yearn to have them reunited. You also fear for them since the world is literally against them in so many ways.

Just when you think that maybe the whole world is against them and there is no love left, you get this scene that gives you some hope.

[Clip runs from 1:07:33 to 1:08:57 of the film and shows Tish and Fonny looking at a loft with Levy, the young landlord. Levy is willing to rent to them because he “digs love” and says that sometimes that’s all that makes the differences “between us and them.”

— A beautiful way to explain how love is the way and that all of us, black, brown, white, yellor, or green see what Tish and Fonny have.

We all wish that every human was as thoughtful and kind as Levy. His words are so moving and meaningful. It’s the statement of the anti-theme almost. The counterpoint to the whole movie. What we should all strive for.

There is another love story of sorts in the Society > Domestic subplot with Tish’s family. There are several scenes that capture how far Tish’s family (and Fonny’s dad) will go to not only help Tish but to also prove that Fonny is innocent.

The most heartwarming scene is when Tish’s mother Sharon flies to Puerto Rico to find Fonny’s accuser. That’s an interesting way to show a mother’s love for her daughter. Sharon knows that the world is against Tish and Fonny as well as their unborn baby. Her love for her daughter drives her to Puerto Rico to confront her accuser in this scene, which is at 1:34:15 to 1:37:27. It’s a powerful scene that confirms what Sharon has thought all along that Fonny’s accuser was told to pick Fonny out. This is a great Truth Wins Over Lies scene. Her sudden cries and sobbing show how distraught she is for hiding the truth. It’s also on theme and raises the stakes another power of 10.

Anne: I wanted to share what Barry Jenkins himself had to say about that scene. This is a quote from an interview in The Atlantic Monthly, and among other things it speaks to the writer’s eye for scene type similarities between wildly different stories. He’s referring here to Regina King, who plays Tish’s mother, in the moment where the traumatized rape victim breaks down screaming:

“But there’s trauma, and there’s no place for trauma to go but out. Someone described it to me as Regina being like Jeremy Renner in The Hurt Locker, sitting there trying to defuse the bomb and she cuts the wrong damn wire.”

Jarie: Yes indeed Anne! I agree that it’s a great characterization of that scene. You feel for everyone and it’s a respectful way to handle it. It also shows the injustice all around.

We now realize that Tish and Fonny may never be together and our heart sinks. It seems hopeless until the last scene where we see Fonny, Tish, and his son, Alfonso Jr., visiting in jail. Finally, the lovers are reunited but the reunification is bittersweet since it’s clearly not fair given that the deck is stacked against him. Fonny “took a plea like so many men”, which seems like a perfect Win But Lose option so he can one day hold Tish and his son in his arms.

If I were to characterize this type of love story, it would be one of Pure Love Torn Apart. It’s masterfully done and used to great effect as the story spine that drives the message of the racism that African Americans face even today.

For writers, it’s a great example of an external genre giving the story enough narrative drive to hold the weight of the message. Hidden Figures did this in the same way by using the Performance > Professional genere to hold the discrimation that Katherine Goble, Mary Jackson, and Dorothy Vaughan faced while working at NASA.

So, if you find yourself wanting to tackle a big problem in your writing, think about how you can build a story around it. Use an external genre that can give it enough narrative drive to hold the big idea you’re trying to get across just like James Baldwin did in If Beale Street Could Talk.

Kim – Thank you, Jarie. That’s a really cool way to think about. It’s like applying specificity begets universality through genre, and I can see that work in other stories, stories where it’s as though the plot is one thing but what it’s about and what it means to us is another, or at least more. Thelma and Louise, Saturday Night Fever, To Kill a Mockingbird. SNF and TKAMB are both global Worldview-Maturation stories as well, so that is another interesting takeaway for me.

Leslie – The Gift Expressed

Shawn describes the Gift Expressed as a choice moment when the protagonist expresses their special gift in a way that is an active choice in response to their crisis question. Having metabolized the shock of the Turning Point Progressive Complication, the protagonist must decide how they will live life in the future. This is usually the Climax of the Global Story, and comes in the ending payoff.

The gift expressed can also be seen as the new strategy the protagonist adopts once their initial strategy fails. They have one way of solving problems that’s worked for them in the past, but when that fails, or as here, the means is taken away, the protagonist must express their individual gift, which involves some kind of sacrifice, if they are going to salvage success in pursuit of their conscious object of desire.

You may know this moment as the Resurrection from Christopher Vogler’s The Writer’s Journey. The all is lost moment of the middle build leads to a decision, but the Gift Expressed is about whether the protagonist can hold on to the lesson they learned then, and apply it in the future. Was it a fluke, or has the protagonist really changed?

In The Virgin’s Promise, I see this moment as a Combination of “Wanders in the Wilderness” and “Chooses Her Light.” Wanders in the wilderness is a crisis moment, the protagonist has abandoned the dependent world and the question for the climax is whether the protagonist can stand on their own two feet. In other words, it’s one thing to practice individual expression in secret, but can you do it in the light of day?

So let’s look at Fonny and Tish and how this operates in their story.

Fonny

BH: Tish tells us that woodcraft saved Fonny from “the death that awaited the children of our age. Kids were told they weren’t worth shit, and everything they saw around them proved it.” But Fonny had his art, and Tish’s friendship, and that was proof enough against it.

MB: Fonny tells Daniel there are two things in his life he needs: Wood and stone and Tish. In other words, he can survive and put up with the world as it is, so long as he has his individual expression and love. When he’s deprived of both, what does he do? He can hold out in jail because he believes justice could prevail, that Tish and her family could succeed in their efforts.

EP: Fonny lies in bed in jail remembering or imagining working with wood. He seems to realize that individual expression isn’t just about what you share with the world, because that can be taken from you. It has to be more than that. This revelation fortifies him for learning that the effort to get him released has failed. He tells Tish that he’s going to build a table that their family is going to eat off of for a long time. And this seems to fortify Tish for facing life as it is and adjusting her goals to survive.

Early on, Fonny solves problems and endures the world as it is through giving and receiving love and his individual expression (for example, he worked jobs, but withholding himself for his art). When those means of coping are taken from him, he must decide to draw strength within himself—what is the source of the love and individual expression? He must remember that they are within him.

Tish

BH: Given the odds and the fact that Fonny is in jail, how will Tish manage to raise the baby? Tish’s answer: we’ll get you out. This is a naive hope and trust that the world will make sense, that justice will be done.

MB: When she has to metabolize the bad news that Victoria Rogers is in Puerto Rico, Tish has already been fortified because her Mom explains that she’s not alone, “love is what brought you here, and if you trusted it this far, don’t panic now, trust it all the way.” Tish finds evidence in remembering how she and Fonny secured the loft. Fonny can see the possibility in the loft, even when she can’t. Levy’s decency and Hayward’s determination seem to provide hope.

EP: The effort to free Fonny fails because Victoria cannot face returning to New York City. What are they going to do? Trusting that things will work out is no longer enough. Tish must break the news to Fonny, but his key message fortifies her for what’s to come. Tish realizes “we have to live the life we’re given so that our children can be free.”

In the past, Tish solved problems by trusting that things would work out as they should. In part this is a result of the love and support she receives from her family. When she can no longer trust that things will work out the way she hoped, she must face the world as it is, and she’s willing to do this, so her son can be free.

Kim: What is your take on the genres at play here? What genre do you perceive as global and what genre(s) are companion and subplot?

Leslie: I agree with Anne that we have a global Worldview shift happening here. I would say it’s definitely what Shawn would call squishy. Reasonable minds could disagree about whether Tish is having a Disillusionment or Maturation arc. I think the difference in large part will come down to what you bring to the story at the moment you receive it.

But one thing I’ve been thinking about lately is what’s happening when you have a primarily nonlinear story. I’m not talking about a flashback or two, but when most of the events are revealed out of order. I first talked about this in our Jane Eyre episode. When the writer breaks structure in this way, it pulls the reader out of the narrative dream of the story—not haphazardly, it’s still a story and we can still identify the landmarks of story structure—but usually the writer has a point that’s beyond the story. Interestingly, we are deeply immersed in Tish and Fonny’s world and community, even as we’re shown another episode from their lives. (It’s as if someone like the ghosts from A Christmas Carol is showing us particularly events to help us see something we would have missed if they gave us the straight story.)

The nonlinear structure changes how we make sense of the events and what they mean to us. It’s not as much about the protagonist’s journey because they experienced it linearly. So it changes what the events mean to us. Every new scene changes what we know—and what we think we know—about the story, but also the world. It causes us to reflect, more than a typical story, on our own lives and actions. At least that’s my experience, and I think I’m not alone in that. It feels as though the reader is on their own Worldview-Revelation journey, one in which they lack key information needed to make a wise decision—which is why I connected this to nonfiction and thought this might be “Big Idea Fiction.”

So what’s the point? This brings me back to our discussion from two weeks ago about different types of love stories. I’m in working-hypothesis mode here, trying to figure some things out, so explore this on your own and see what makes sense to you.

Perhaps one of the differences between a more straightforward Courtship Love story, like Sense and Sensibility, and ones like Brokeback Mountain and If Beale Street Could Talk is the question the reader asks. Conventional Courtship Love raises the question, will the lovers commit? Brokeback Mountain and If Beale Street Could Talk seem to ask, should they try given the obstacles they face? In a conventional love story, the biggest obstacle is found within the lovers themselves. But for Tish and Fonny, Ennis and Jack, there is no question in my mind that, absent the system preventing their being together, those lovers would commit. And we get that feeling pretty early on. The lovers are soul mates, meant to be together. And they know it too.

Assuming all of this is true, I wonder if one reason for the differences between the ending in the novel and that of the film come down to perspective. What I mean is, if the question is, should people like Tish and Fonny pursue love in spite of the system (and maybe also whether Sharon and Joseph were right to shelter Tish from the world as it is)? So maybe, should subjugated people choose love? With the open ending in the novel, James Baldwin doesn’t offer a clear answer in 1973. Barry Jenkins in 2018 suggests, in hindsight, they should choose love, and that we’re all better off because people like them did. That’s just my take on the story. Baldwin and Jenkins wouldn’t necessarily agree, but a story like this seems intended not to tell us what to think as to invite us to think.

Valerie – Empathy

This week, I’m continuing my study of empathy and how it’s created. As I may have mentioned already, empathy is an essential element in stories because it’s what gets us to connect emotionally with the protagonist. When I say empathy, I mean that the reader has to specifically empathize with the protagonist. She can empathize with other characters, but she must empathize with the protagonist. Empathy is like the secret sauce that grabs a reader and makes her root for the protagonist.

Empathy, of course, is not sympathy.

- Empathy means relatability: can the reader relate to the protagonist on an emotional level. Does she know what it’s like to feel the way the protagonist feels?

- Sympathy means likeability: does the reader like the protagonist, or not?

While empathy is essential, sympathy is optional (although it helps!).

Last week, we heard a quote from Shawn where he explained that to create empathy at the macro level, we need to use the heroic journey. To create it on the micro level, we need to clearly articulate the protagonist’s objects of desire.

What happens with stories, like If Beale Street Could Talk, that don’t follow the heroic journey? Can a writer develop empathy without it? I think the answer is yes (because Tish is most definitely a character we can empathize with). Although I suspect it’s easier to use the heroic journey (because empathy is built-in to the structure), it isn’t strictly necessary.

So, how was empathy created here in Beale Street?

First, Tish’s objects of desire are crystal clear. She wants Fonny to be released from prison. She needs to mature. The audience can easily relate to both want and need here, and because they’re so well defined, we know exactly what to cheer for.

I think we need to take it a little further than simply identifying the objects of desire, though. I think we also need to articulate why our protagonist wants and needs the things she wants and needs.

Tish wants Fonny to be released because (1) he’s innocent and (2) she loves him and wants to build a life with him. Those are powerful reasons to root for Fonny’s exoneration. But, she needs to mature because she’s so naive that unless she matures, even if Fonny does get out, their relationship will fail.

Ok, so that’s the objects of desire and the “big meta why” taken care of. But is there more to creating empathy than that?

Yes, I think there is.

Empathy means that we can relate to a character, but how exactly is that relationship created? Well, it’s through character development.

Character is revealed through the actions the protagonist makes under pressure. This is true in stories because it’s true in life. You’ve heard the adage “actions speak louder than words”? Well, that’s what I’m talking about here. Let’s take a real life example:

You and your colleague have to talk to your boss about a difficult situation; perhaps you both feel you deserve more money. Your colleague nominates you to have the conversation but promises that he’ll back you up. So, you go into the meeting, it’s challenging and confrontational. Your boss questions your colleague who then says it was all your idea and he’s quite happy with the salary that he has.

While your colleague said he’d support you (which would indicate bravery), his actions reveal him to be a coward.

So, how do we reveal our characters? That’s where the turning point, crisis and climax come in. The turning point throws the protagonist into crisis. She’s under pressure and must make a choice. The decision she makes will reveal who she is.

Tish is faced with one incredible crisis after another. Time after time her character is revealed to be that of a strong, brave, loyal woman with integrity. Tish is very easy to empathize with, and any one of these qualities would have been enough. This is one of the reasons why I think the ending is a bit disappointing—but I’ll get to that in a minute.

Robert McKee says that to create empathy, the writer must expose a core of goodness or humanity in the protagonist. Even if the character is nasty, there must be something of good in him because we can’t relate to pure evil.

This is what Save the Cat is all about. Blake Snyder recommends having your protagonist do something good early in the story so that the reader will connect. There’s a couple of caveats to that though.

The “something good” has to flow naturally from the story and it has to be relevant to the story. If Tish had saved a neighbour’s cat from the tree, sure, we’d know that she’s kind, but it doesn’t in any way prepare her for the obstacles she’s about to face and it doesn’t have anything to do with the film. That might sound like a bizarre example, but unless you take the time to consider why Snyder is making these suggestions, you won’t really be creating empathy.

Now to the ending: Beale Street provides an opportunity for us to talk about the other side of empathy, and that is catharsis.

Once we’ve gotten our readers to emotionally engage with a story, we must also give them an opportunity to release that emotion and return to homeostasis. Beale Street’s negative ending robs the audience of catharsis—and that, in my opinion, is dangerous territory. It runs the risk of leaving the audience dissatisfied.

Think about it logically: as writers we’ll spent a great deal of time and effort getting our audience to make an emotional investment into the story we’re telling. That investment has to mean something. If we create a situation where the reader experiences heightened emotions (they’re excited, nervous, thrilled, terrified, anxious and so on)—we have to give them a chance to come down off that high.

That’s part of what the ending payoff does. Stories don’t have to end happily, but they do have to provide catharsis. Positive and ironic endings will provide catharsis. Purely negative endings don’t and Beale Street ends completely negatively. The protagonist we’ve come to care about has gone from a vibrant young woman, to a single mother who is merely surviving. All that strength and bravery is now needed to get through the day. In that last visit with Fonny, Tish is the embodiment of hopelessness.

Yes, it seems that they have a date for when Fonny will come home (that’s what Alonzo keeps writing) but the date doesn’t provide any joy for Fonny or Tish; it’s not something to look forward to. Instead, there’s a sense of sadness and despair. Those emotions are shared with the audience and the film ends on a low note.

Of course, I understand the context of this story. I’m not expecting sunshine and roses; that wouldn’t ring true, it wouldn’t be satisfying and would make light of a serious situation which is the very last thing we want to do.

What I’m suggesting is that, in order to provide catharsis, some glimmer of hope could have been highlighted. They’re already in the story, but Tish doesn’t see them, and we need her to see them. Remember, we as the audience, have connected emotionally to her. Stories teach us about change so through her, we’re learning how to handle this extremely difficult situation. If she gives in to hopelessness and despair, so do we.

Intead, we need to see her recognize Alonzo, the lawyer and the man who rented the room to them, as the hope for the future. We need her to believe that not everyone is like the cop.

Unfortunately, that doesn’t happen and Tish’s last voiceover combined with the visit to Fonny, leaves us feeling that nothing will ever change or improve, and there’s no point in even trying. All that emotion we’d built up following Fonny’s case and their love story, has nowhere to go. There is no catharsis.

Kim: I think ending the story this way is very important. To me we must experience that sense of being trapped, helpless, and hopeless, feeling that nothing will ever change or improve. To me, that is what this story is about. And I don’t think a tidier ending does that job.

Anne: The New Yorker’s film critic Doreen St. Félix had something to add to this point:

At the end of Baldwin’s novel, Tish and Fonny’s baby is born wailing; Fonny’s father, whose boss has discovered him stealing money to help pay for Fonny’s trial, kills himself. Jenkins reportedly shot a version of this scene, but later decided to omit it. Had he included it, “Beale Street” would have been a vastly different and, perhaps, better film. It also would have given us more of the pain that we’ve already endured. Instead, inside of Jenkins’s love story, we get, for a moment, to trust.

I’d like to backtrack to Valerie’s comments about catharsis, because I agree that neither the novel nor the film offers it.

I’m not Baldwin scholar, but I’ve spent quite a bit of time with the novel and with reviews and analyses of it and of this movie. Catharsis literally means “cleansing,” and I would say that I experienced a kind of post-story catharsis, if there is such a thing.

I left the text (both times) more “haunted” than “cleansed,” and to the extent to which I was willing to let its truths sink in and take root in the weeks following my first reading of the novel, I’ve been gradually more awakened by it. Then, when I started watching the movie the other day, I started crying from the opening scene and basically kept crying.

If I absolutely had to guess what Baldwin’s intention was, I imagine he’d probably tell the reader, “You don’t get off that easy. I’m not going to do your internal house-cleansing for you.”

I think he specifically and deliberately withholds catharsis because he specifically and deliberately wants the reader to keep working. In this respect, the book might be what Leslie has brilliantly termed a work of Big Idea Fiction.

Barry Jenkins, the screenwriter and director, softened that complete withholding of catharsis a little by changing the ending to say that Fonny took a plea deal, and carrying us through about four or five more years as Tish and little Fonny Junior continue to visit him in prison.

But I’d like to play the last two sentences of the novel from the audiobook:

TEXT OF AUDIO CLIP: Fonny is working on the wood, on the stone, whistling, smiling And, from far away, but coming nearer, the baby cries and cries and cries and cries and cries and cries and cries and cries, cries like it means to wake the dead.

Some critics interpret that as a sign that Fonny (who’s been beaten and put into solitary confinement) doesn’t, or won’t, survive the death of his father. Each time I’ve gone through the ending of the story, the ambiguity of hope and despair remains the same: balanced on a razor’s edge, unresolved, left to the reader to keep thinking.

Kim: That’s so interesting, the novel ends even lower. It feels cautionary tale for the audience: this is what happened and if you don’t demand change this is what will continue to happen. Because we don’t experience a definitive ending, it’s almost as though the audience is faced with the Crisis, Climax, and Resolution. The end of the story is our Turning Point Progressive Complication. Even though I can technically see the Love story elements, I never once thought of it as a Love-Courtship story. It never seemed like the question. From the very first opening shot where we see on-screen text, it signaled Society to me.

“Beale Street is a street in New Orleans, where my father, where Louis Armstrong and the jazz were born.

Every black person born in America was born on Beale Street, born in the black neighborhood of some American city, whether in Jackson, Mississippi, or in Harlem, New York. Beale Street is our legacy. This novel deals with the impossibility and the possibility, the absolute necessity, to give expression to this legacy.

Beale Street is a loud street. It is left to the reader to discern a meaning in the beating of drums.” – James Baldwin

(Sidenote from Anne: This is an error in the movie. Beale Street is in Memphis, and is considered the birthplace of the blues.)

Because Fonny and Tish commit early on, the life values don’t ever feel like Love and Hate (attraction and repulsion/avoidance) but all about Power and Impotence. To me, it’s almost as if the Love story is part of the specific setting required for a Society story to play out. When comes to a controlling idea/theme, I still see Love as a Big Meta takeaway for this story, but not the only one.

The cautionary tale seems to be in line with the negative Society story: Tyrants beat back revolutions by co-opting the leaders of the underclass.

In this case, we see this playout in a microcosm of Society, so it’s less overt, but the pattern remains.

- The Tyrant is systematic racism, referred to as “the white man” in several places. The revolution is for justice. It begins by Fonny throwing the man who harrassed Tish out of the store, and Tish standing up to the officer, “He’s not a boy, Officer.”

- In terms of co-opting leaders of the underclass, the victim, Victoria, already feels like all her power has been stripped away and therefore can’t exercise the power that she has to see justice done. We don’t see the scene where she is presented with the line up, but I found her line of dialogue telling, “The told me to pick him out, so that’s what I did. I picked him out.” I got the impression that the cop made it clear who he wanted her to pick.

So for the cautionary tale, it seems like: Tyranny reigns when those with the power the expose hypocrisy are paralyzed with fear.

Love, on the other hand, feels like the prescriptive tale: Love prevails when we choose to love, despite external circumstances, through the simple act of continuing to show up.

It comes down to the two most fundamental aspects of human existence: Fear and Love. And I guess we get to decide how the story ends.

Listener Question

To wind up the episode, we take questions from our listeners. This week’s question comes to us from Ground Your Craft participant Sarah M.:

How does satire succeed or fail? Is the key to satire in the 5-leaf genre clover—using absurdism, meta-ness, and genre mashups, or can one write a satire that works within a single genre? It seems hard to do without writing “on the nose.”

Jarie: Thanks for the question, Sarah. Sarah is not the only person that has asked us this question. I’ll start by giving everyone my definition of Satire.

Satire uses humor, irony, exaggeration, or ridicule to make fun of a person, idea, or institution to not only entertain but to convey information and makes people think.

We have looked at a few movies on the Round Table that dealt with satire like The Spy Who Dumped Me and Adaptation with the latter using absurdism to make the satire “work.”

I feel you can write satire that works in a single genre and not have to rely on absurdism to make it work. One of the best examples of satire out there is The Onion.

The beauty of what The Onion does is that it takes everyday stories and makes them into satire that is sometimes hard to recognize as satire. I think that’s the art in all this.

The comic stripe Calvin & Hobbes does the same thing in that it brings up deep and moving issues through the lens of Calvin, a creative and rambunctious kid who’s ever faithful stuffed animal Hobbes, points out the folly in his thinking.

If you want to see how to make fun of marketing and what author doesn’t, then Tom Fishburne’s Marketoonist is the place to go for that. Tom’s work is compelling because he is making fun of himself since he used to be a marketeer.

Satire is tough to pull off since the reader or viewer has to understand what is being made fun of. You’re right that it can seem “on the nose” since setting up for the sarcisim has to be done perfectly or the reader/viewer just won’t get it.I don’t have any rules of thumb or advice on writing satire. Frankly, I’m not that good at it and try to avoid it like a politician avoids kissing too many ugly babies. What I can say about satire is that it should be appropriate for the character and in voice. It should move the story forward or provide some truthiness that cannot be conveyed in any other way. I’d also read masterworks of Satire, like Catch-22 or Slaughterhouse 5 or watch The Colbert Report, to get a better sense of how they work and try it out. I think Satire is kinda like jokes—you know you have a good one when someone laughs.

If you have a question about any story principle, you can ask it on Twitter @storygridRT, or better still, click here and leave a voice message.

Join us next time to find out what Leslie discovers about Action stories on the epic scale when we take on the 1998 mega disaster movie Deep Impact. Why not give it a look during the week, and follow along with us?

Your Roundtable Story Grid Editors are Jarie Bolander, Valerie Francis, Anne Hawley, Kim Kessler, and Leslie Watts.