This week, Valerie looks at Marriage Story in order to study a story’s Three-Act structure. This 2019 film was written and directed by Noah Baumbach.

The Story

-

Beginning Hook – Nicole and Charlie Barber, who live in New York City, are in the process of separating and have decided to split amicably without the help of lawyers. But, when Nicole gets a job in L.A. she moves there with their son, Henry. One of the producers on Nicole’s new show gives her the name of a divorce attorney and recommends she contact her. Nicole has to decide whether to use an attorney or not. (Using an attorney would help her protect her assets and custody of Henry, but would make her continued relationship with Charlie, as Henry’s father, even more difficult. She decides to hire the lawyer.

-

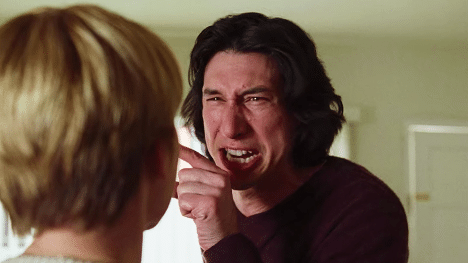

Middle Build – Nicole serves Charlie with divorce papers, which forces Charlie to hire his own lawyer. The divorce proceedings get ugly and when the court says it will send a social worker to observe both parents with Henry, they decide to try and work things out between them. Their attempt at a rational discussion quickly dissolves into a heartbreaking argument and in the end, their relationship—and their situation—is worse than it was before. (Quick side note here: there are many beautifully crafted scenes in this film, and I think the fight scene between Nicole and Charlie at the end of the middle build will go down in storytelling history as one of the greatest.) The social worker observes Charlie with Henry and seems unimpressed, the “knife trick” goes horribly wrong, the social worker departs in horror and Charlie ends up on the kitchen floor bleeding profusely. It truly is an all is lost moment.

-

Ending Payoff – Charlie gives Nicole what she wants in the divorce and returns to NYC a broken man. Meanwhile, Nicole discovers that her lawyer changed the balance of custody from 50/50 to 55/45, which isn’t what she wanted. When Charlie reads what Nicole had written about him prior to their divorce (the opening voice over) he realizes that Nicole did, and does, love him. When Nicole learns that Charlie has taken a job at UCLA to be closer to Henry, she becomes more flexible with the custody arrangement.

Genre: Love Story > Marriage (but with strong society undertones); Worldview > Disillusionment (Charlie), Status > Sentimental (Nicole)

Additional comments:

Leslie: One thing that’s interesting to me about this story is how similar and yet different it is from Mrs. Doubtfire, which we discussed last season. The two stories deal with a similar situation—a couple navigating the end of marriage when there are kids involved—but the genre, style, POV, and narrative device create very different stories.

Valerie: I agree. These two films couldn’t be more different. The beginning hook of Mrs. Doubtfire leads us to believe we’re going to get something in the ballpark of Marriage Story, but I think it takes a right turn in the middle build and shifts to a performance story, complete with massive core event performance during the dinner scene. It works (structurally) as a performance because the beginning hook also includes performance conventions and obligatory scenes, and turns on the global value for performance. It’s not a huge surprise given the casting of Robin Williams; filmmakers certainly would have wanted to capitalize on his comedy skills.

Valerie – Beginning, Middle, End

I’m studying the beginnings, middles and ends of stories this season, particularly in light of Shawn’s new method for breaking down the middle build. But before I jump into that, I want to touch on a couple of other topics because Marriage Story is such an expertly crafted film.

The film opens with a massive voiceover. Now, voiceovers can be a bit like chewing tin foil. They’re used a lot and are often unnecessary; one example is The Shawshank Redemption. The voiceover there is famous (or perhaps infamous), but when we studied that film, I noticed that it’s also completely redundant. Everything that Morgan Freeman says we can see dramatized on screen. We don’t need him to tell us.

I grumble a lot about voiceovers (and cliffhangers for that matter) and I want to take a minute today to refine my perspective. Voiceovers and cliffhangers are simply tools in the writer’s toolbox. In and of themselves, they’re neither good nor bad. What we’ve got to do is understand what each of the tools in our toolbox does; what do they do well, what don’t they do so well. That way, we’ll know which of the tools we need to shape the story we want to tell.

Marriage Story opens with two voiceovers, and they work brilliantly. This film is about two people who love each other, but who can no longer live together.

The primary antagonist here is society (represented by the lawyers, the judge, the social worker, Nicole’s family and even the actors in the theatre company). Through the voiceover, Baumbach immediately created empathy for both Nicole and Charlie. And empathy for both characters is essential—without it, the film wouldn’t work as well.

I said that society is the primary villain, and at the most macro level, it is. However, if we narrow our focus a bit and look at the story through the hero’s journey lens, we also see Nicole as an antagonist. But, Marriage Story is filled with shapeshifters, so even though Nicole can be viewed as an antagonist, at any given moment she’s also a protagonist.

This film has so many layers to it, it’s truly a stunning piece of writing. It’s like a kaleidoscope; if you shift your view just a bit, the whole story changes. This is a marriage love story, there’s no doubt about that. But as we’ve said many times here on the podcast, there can be elements of a number of genres within one story. Here, the society genre is so strong that if Charlie weren’t such a complex character, we could make a case for a society > women’s global genre, or society > domestic for that matter. Charlie might be selfish and myopic where Nicole’s feelings are concerned, but he’s not a tyrant. There’s never any doubt that he loves his wife and son. Yes, Nicole accuses him of gaslighting her but that’s during the big fight scene where they’re both saying things they don’t really mean or believe.

We know Charlie is a good man. Not perfect, but a good man. Likewise, we know Nicole is a good woman. Not perfect, but a good woman. That’s part of the beauty of this story.

He’s not a tyrant. She’s not a bitch. They’re brokenhearted people in an impossible situation.

So, let’s take a look at the Act structure for a glimpse at how Baumbach pulled this off.

I think the beginning hook and ending payoff are fairly straight forward in terms of their function. So I want to dive right into the middle build. I’ve given a lot of detail about Shawn’s new approach to the middle build in past episodes, so if you want more information that what I’m about to give you here, you can go back to the beginning of season seven, or read Action Story: The Primal Genre, by Shawn Coyne.

The first part of the middle build (MB1) is the calm before the storm. The protagonist has crossed into the extraordinary world armed with only the beliefs, skills, tools and knowledge he brought with him from the ordinary world. The middle build belongs to the antagonist because the extraordinary world is the antagonist’s home turf. So, whereas the antagonist is right at home, the protagonist is a fish out of water, and is trying to navigate this strange new environment the best way he can.

This literally is the case in Marriage Story which is why, at a macro view, we can see Charlie as the protagonist and Nicole as the antagonist. The ordinary world is very clearly established in the beginning hook as New York City. The extraordinary world is Los Angeles; it’s where Nicole is from, it’s where her family lives. She literally has home court advantage.

As the middle build begins (the inciting incident of MB1), Charlie crosses the threshold of Nicole’s family home. We see him behaving as he always does; we see his “code 1.0” as Shawn calls it, in action. In the past when he’s gone to G-ma’s house, he was greeted warmly. G-ma loves him, Cassie loves him, he’s welcome. So this is part of the belief structure he’s brought with him from the ordinary world. He’s in the extraordinary world now though, and here, Nicole’s family can’t talk to him and he can’t stay at G-ma’s house.

From this point forward, everything Charlie thought was true, turns out to be untrue. The world doesn’t work the way he thought it did. By the end of the story he’s completely disillusioned. It’s almost too much to bear.

The turning point is when the antagonist targets the protagonist. This happens during the mediation scene when Nicole’s lawyer raises the issue of residency. Over the course of the scene Charlie realizes that, in the eyes of the court, they are not a New York family. They’re an L.A. family. This means that, unless he moves to L.A., he can’t be an active part of his son’s life. The crisis then, is will Charlie try to fight this opinion of their residency, or will he give in?

In the climax, Charlie chooses to defy the antagonist and so gets a new lawyer; one that will fight dirty. The climax of MB1 is where the shadow rises. It’s when the antagonist actively asserts his power. As Shawn puts it, it’s “a monstrous execution of force that the protagonist is not equipped to handle”. Well, we certainly see this in court when Nicole’s lawyer (who is acting on behalf of the societal antagonist and Nicole as antagonist) goes after Charlie with both barrels. The protagonist isn’t equipped to handle the antagonist’s power, and responds in a way the antagonist isn’t expecting. In Marriage Story, this is when Charlie’s lawyer turns the tables and attacks Nicole.

Why am I talking about the lawyers here, rather than Charlie and Nicole? It’s because Charlie and Nicole have lost their voices. The lawyers are speaking for them, and so momentarily fill the roles of protagonist and antagonist. Everyone is a shapeshifter in this story; remember, the archetypical roles are roles, not characters.

In the resolution, which is the midpoint shift (aka midpoint climax or the point of no return), the court declares them an L.A. family (temporarily) and appoints a social worker to observe both Nicole and Charlie with Henry.

The second part of the middle build (MB2) is the chaos phase. The protagonist has no idea what’s going on, he has no strategy for coping with what the world is throwing at him. When the protagonist is in chaos, the entire story and all the other characters in it, are in chaos too.

The inciting incident of MB2 is an unexplained event that both protagonist and antagonist need to deal with, and neither of them is fully equipped. This is the amazing fight scene between Nicole and Charlie. By the end of this scene, Charlie is destroyed; he’s curled up in the fetal position clinging to Nicole. Nicole, as the antagonist, finishes the scene the stronger of the two. She’s still standing. She’s no longer crying. She’s the one to give comfort, she doesn’t need to receive it.

The turning point of MB2 is the protagonist’s All Is Lost moment. This is when the social worker observes Charlie and Henry. There’s a sequence of scenes here that ends with Charlie lying on his kitchen floor, bleeding. That is his All Is Lost Moment. He knows the social worker won’t file a report in his favour. He will lose his son.

The crisis of MB2 is the global crisis of the story. This is when the protagonist, knowing that he won’t get what he wants, starts to question the meaning of life. He tries to figure out what he’s supposed to do now. We see Charlie, back in NYC, utterly lost. He has no words to articulate how he’s feeling, and so he sings them—another incredible scene.

Typically, in the resolution of MB2 we see the protagonist preparing to fight the antagonist. Unfortunately, Charlie has no fight left in him. He can’t go up against Nicole again. If he wants to be with Henry, he must move to L.A., and that’s what he does.

The ending payoff of this film is very short and that’s probably just as well. By the time the story reaches this point we’re all emotionally exhausted—the characters, the viewers…everybody. We hope that Charlie has returned to L.A. in time to rebuild his relationship with his son, although it looks like he’s got a hell of a lot of work to do. Nicole’s new boyfriend (played by Newfoundlander Mark O’Brien!) has stepped into the father-figure role. And as we see during the final scene, Charlie has literally and metaphorically, become a ghost.

This is the tip of the iceberg for this film. The more you watch it, the more you’ll discover.

Kim – Core Event for Love-Marriage and Morality

About Core Events

I am studying Core Events this season, which is the big moment of change that pays off a story and is specific for each genre, because it represents a peak moment when the core life values (that represent the core human need) are most at stake, meaning the protagonist has the most to gain and the most to lose. This tension and shift in life values evokes the core emotion and is the ultimate payoff of reader expectations that have been set up and built up over the course of the story.

These elements are known as the Four Core Framework and represent the heart of each genre: the human need is represented by specific life values that evoke the core emotion and culminate in the core event. The Core Event is also the answer to the question that is raised by the premise in the BH.

About Today’s Genre – Four Core Framework

So what is the question raised by today’s genre?

Primal Question For Love Genre, in general, is: will the lovers commit to each other? In an Obsession subplot the answer is no (because the lovers don’t mature beyond desire). In a Courtship subplot the answer is typically yes. But in the case of a marriage plot, the lovers have already committed so the primal question takes on a different quality, which we’ll talk more about in a moment.

Regardless of the sub genre, the Four Core Framework of Love is still the same: human needs tank is Love, the core values of Love/Hate, expressed in the core event Proof of Love moment, that evokes the core emotion of romance. But in a marriage ploy, the core emotion has a slightly different quality—it’s about something deeper than the butterfly feelings of romance. It’s deep intimate love and connection.

Shawn on Love-Marriage stories: The Marriage story concerns a committed relationship that certainly had early stages of passion and is now at a crossroads. This story takes love into realistic realms and may have a negative inciting incident such as betrayal.

While Worldview-Maturation is baked into the Love genre, we often see Morality internal genres paired with Love-Marriage stories. Which makes a lot of sense — lovers must mature in order to enter into a genuine committed relationship, but in order to sustain a committed relationship and advance to genuine intimacy, lovers will be held to a higher standard and challenged in new ways.

Primal Question for Morality: will the protagonist sacrifice their own want and put the needs of another above their own, or will they choose to selfishishness?

The Four Core Framework of Morality: human needs tank is self-transcendence, core life value is selfishness/altruism, expresses through the core event of The Big Choice, when the protagonist must choose between sacrifice or selfishness, that evokes the core emotion of either Satisfaction or Contempt, depending on their choice.

This leads us to how today’s story executes these elements in the core event …

About Today’s Story

For today’s film, I’m going to discuss two scenes. Something I’m noticing as I study core events is that there are often two scenes that feel like two halves that together make up the core event. It’s easier for me to see this cause/effect relationship, a sort of set up and payoff within the ending payoff, than it is for me to narrow to one precise moment. Maybe it’s that the precise core event moment only seems to make sense in the context of the other moment, whether it precedes or follows it.

Scene between Nicole and Nora – at Nicole’s house, a party of some kind, Nora tells Nicole that things are almost done with Charlie and the divorce. Because Charlie gave up on New York, Nicole gets LA, because Nicole gave up on the MacArthur Grant, Charlie isn’t asking for any of her show money. But then Nora tells Nicole that when Charlie is in LA the visitation split will be 55/45, so Nicole will get one more day with Henry every two weeks. Nicole didn’t want that, but Nora changed it last minute so that Charlie couldn’t brag about getting 50/50. Nora tells Nicole to enjoy the win.

Scene with Charlie on Halloween – Charlie arrives at G-ma’s house and everyone gets ready to dress up and go trick or treating together. Charlie tells Nicole he took a residency at UCLA and is going to be directing two plays, so he’ll be in LA for a while. Nicole can see the effort and is proud of him. In the other room, Henry finds the letter that Nicole wrote about Charlie that she refused to read during their appointment with the mediator (at the opening of the film). Charlie sits with Henry and listens to him read and then reads the rest aloud, tearing up at the end when Nicole said that she would always love him even though it doesn’t make sense anymore. Nicole is standing in the doorway listening, with tears in her eyes too. The family goes trick or treating together and then when it’s time to say goodbye, Nicole sees how tired Henry is and asks Charlie if he wants to take him home rather than making Henry come to dinner. Charlie says, “But it’s your night.” Nicole insists and Charlie carries Henry to the car. On the way, Nicole stops Charlie and ties his shoe for him.

The scene on Halloween feels like the true Core Event, but Nicole’s proof of love about giving Charlie the extra night with Henry is set up by the scene with Nora, as though Nora’s announcement of the arrangement is a turning point for Nicole … how is she going to use the power that she has? This prompts the primal questions of Love-Marriage and Morality: will lovers who no longer want to be in a committed relationship continue to love each other or devolve into hatred? When given the chance to behave selfishly, will we?

But what we see is the core events of Proof of Love and Big Choice of Selflessness by both parties. When Charlie takes a residency in LA to be closer to Henry we feel the same core emotion as Nicole – not satisfaction in a smug “I win, you lose” kind of way, but proud of him for being the man, the father, that she loves. And then when Nicole lets Charlie finish the letter she wrote, have the extra night with Henry, and tie his shoe, we feel a deeper sense of romance, not one of sweet giddiness but a weighty ache that means so much more.

This leads to what I see as the Big Meta Why of Love-Marriage and specifically Divorce stories: how can we still love each other well when we’re no longer in a romantic relationship? By finding a different version of commitment and intimacy that is separate from desire, one where we give our gift (of love) to one another selflessly.

Leslie – Point of View (POV) and Narrative Device

As I often say, if genre is what your story is about, POV and ND combined is the way you deliver the story to your reader or viewer. That’s why I firmly believe that your POV and narrative device choices are the most important decision you make after the global genre.

The narrative device or situation is the content or substantive element of the way you deliver the story to your reader and answers the questions, who or what is the source of the story, when and where is that source located in relation to the events and characters of the story, who is the story for, and why is it being told? POV is the technical element, which tells us whether it’s first or third-person, for example. It answers the question, how do we create the effect of the narrative device?

POV and Narrative Device give writers useful constraints to make decisions that support the story you want to tell. I explore how to choose your POV in a Bite Size episode on choosing your POV, which can be found here. You can find my article on narrative device here, and on POV here. If you have questions about POV and Narrative Device, I’d love to hear them. Leave a comment here, get in touch through the Guild, or submit your question through my site, Writership.com/POV.

What’s the narrative opportunity presented by the premise?

I start my analysis by looking at the opportunity presented by the premise. The premise is a concise statement about a specific character(s) in a setting with a problem.

Nicole and Charlie are two flawed married partners who care about and love their son, Henry, but who can no longer get along as a couple. When the story opens, they’re living in New York City, but soon Nicole and Henry move to Los Angeles.

In general, marriage stories create the “opportunity” to portray stereotypes, casting one partner as the villain and one as the victim. But they also present the opportunity to reveal the deeper truth that, in most relationships, no one is a villain or victim all the time.

Here the creators chose the latter path, which offers a more useful controlling idea for the audience and an opportunity for real catharsis. What’s more, the specificity of the problems these characters face makes the story universal.

Although we’re talking about marriage, you could write a similar story about any complex relationship, for example, in a professional or political context. And the central question of the divorce case about whether Henry, Nicole, and Charlie are a New York or LA family could be any ill-defined problem loaded with emotional baggage. These problems are not solvable using black-and-white thinking. To have any chance of coming out on the other side requires the worldview shift that Shawn calls breaking our cognitive frame. We just aren’t capable of seeing a workable solution while we’re mired in big emotions and old thinking.

To me, the essence and genius of this film is that it shows how the story we tell ourselves about what’s happening is often the real problem. That’s just another way of saying we need to break our cognitive frame: The stories we tell ourselves get in the way of seeing options and realizing that the way we try to meet our needs may be in conflict, but our needs themselves seldom are.

To take advantage of the opportunity presented by the premise, the creators must show both partners at their best and worst struggling to change the stories they tell about themselves and their situation. One way to show the struggle is to give us a view of what the characters are thinking and what they actually do. This is difficult to do in film, so how do the creators here accomplish this? They pay close attention to the POV and narrative device.

What’s the POV?

POV is tricky to identify in films without an overt narrative device or situation. But what do the scenes of Marriage Story reflect? The scenes suggest what Norman Friedman calls Neutral Omniscience. We have a god-like narrating presence, but they don’t speak directly to the audience. As Gustave Flaubert explains, “The author should be felt everywhere, and visible nowhere.” They reveal the point of the story through the events they choose to show and how they frame them. The neutral omniscient narrator has access to the words, actions, sensations, and thoughts of all the characters to tell the story. But that doesn’t mean they show everything, or that the events and information they reveal is random.

This POV choice isn’t as popular today as it was during the 19th century, but we still see it in a wide range of stories, including expansive stories, like Jonathan Strange & Mr. Norrell by Susanna Clarke or One Hundred Years of Solitude by Gabriel Garcia Marquz, and in middle grade fiction, like The Wind in the Willows by Kenneth Grahame or The Tale of Despereaux by Kate DiCamillo. But you also see it in smaller gems like Silk by Allesandro Baricco when this POV provides a wider perspective on a narrow field of events.

Other POV choices have constraints by definition. For example, a first person narrator can give us access to the actions, words, sensations, and thoughts of the character, but we’re limited to one character and what they can observe (no outside observations or opinions). Third limited, also called close third or selective omniscience, is similar because it focuses on one character at a time with no outside opinions or observations, but we’re getting an unselfconscious view of the character’s experience. These points of view help narrow the writer’s choices.

But the limits of neutral or editorial omniscient narration come only from the specific narrative device or situation. Every writer should choose, execute, and evaluate their narrative device with attention and intention, but it’s especially important if you’re using omniscient POV because it doesn’t have natural constraints.

What evidence in Marriage Story itself suggests omniscient narration? The film shows us actions and words, but also the implied sensations and thoughts of multiple characters within the same scenes.

Words and actions are easy, but we also observe sensations, for example, when Nicole is unsteady on the stairs from drinking, or when Charlie passes out because he cut himself during evaluator’s visit.

But what about thoughts? How are we able to observe them? The film opens with Nicole and Charlie reading their divorce mediation assignments, though we don’t know that’s what we’re hearing. Along with the voiceover for each, we see flashes of memories that serve as evidence of the propositions in the notes. The context could be love letters, a couples therapy assignment, or an interview. We don’t know, but we make assumptions that are upset when the camera (as stand-in for the narrating entity) pulls back to reveal Nicole and Charlie meeting with their divorce mediator.

Incidentally, another example of this effect, when what we assume turns out to be incorrect, happens when we think Nicole is being interviewed by the evaluator, but it turns out to be a practice session.

The POV choice in these scenes simulates the revelation that something we really believe is true is actually not, or that it’s not the whole truth. The scene-level POV choice creates this effect, and the audience experiences a little of what Nicole and Charlie are going through.

So whether an audience member chiefly sympathizes with Nicole or Charlie in the beginning, by the end, we experience the deeper truth of their revelations and can empathize with them both.

What’s the narrative device?

We have an anonymous narrator, so I’m deciding based on my impression of the scenes and the POV. The omniscient narrator reminds me of someone like Nicole who might write and direct a film after fully metabolizing the divorce to help people who face conflict, particularly partners considering or going through divorce, change the stories they tell about their situation so they can focus on what’s important. In this case her controlling idea might be: Divorcing partners can recover connection and find intimacy through co-parenting when they reframe the stories they tell about their circumstances. (This is not the only message the audience might come away with, but it’s the global controlling idea/theme of the story as I see it.)

As always when there’s no obvious narrator, my analysis is subjective. Reasonable minds could certainly disagree with my conclusion. The point is, it’s useful to use our writer’s imagination to think about what the creators might have been trying to do. That helps us consider the wide range of possibilities for our own stories as well as the techniques we can use to create the effects.

How well does it work?

How well do the POV and ND choices fulfill the opportunities presented by the premise? Using the word genius earlier probably gives away how I feel about this film. Honestly, I say the “opportunities presented by the premise,” but I might also talk about how the POV and Narrative Device setup and deliver the moment of catharsis at the end. We feel hope that we too can change the story we tell ourselves and work out the stickiest of problems, no matter how big or complex.

Final Thoughts and Takeaways for Writers

We like to round out our discussion with a few key takeaways for writers who want to level up their own writing craft.

Kim: When executing your Core Event, look for the setup scene that raises the primary question of the genre/theme again. Having this question resurface intentionally in the ending payoff will cue the life values at stake and set your audience up to feel the core emotion when the Core Event moment happens and the life values shift. This one-two punch will generate maximum core emotion and satisfaction for the audience.

Leslie: POV and narrative device are technical choices that create some of the best magic that exists in our world. It can transmit knowledge (controlling idea) and catharsis (core emotion) from inside the mind of the writer to the minds of the reader. If your story isn’t doing this, take another look at your POV and narrative device. It’s worth your time and attention so that you can fulfill your story’s promise.

Valerie: There are so many takeaways from this film, but I think the key one for me is that as writers, we’ve really got to learn what all these storytelling tools are and how they work. Only by doing that can we make informed decisions about which of the tools will help us shape the story we want to tell.

Listener Question

To wind up the episode, we take questions from our listeners. This week’s question comes to us from Su Kopil on Story Grid Guild.

How do any of the editors use the Story Grid as a plotting tool?

Kim: Thanks so much, Su. So if Plot is what happens in your story—the sequence of events that create the genre arc, then plotting is figuring out what needs to happen. And fun fact: every writer is a plotter, because every story has a plot. It’s simply do you plot best from outside the story (with an outline) or inside the story (line by line from scene to scene)? And this isn’t a moral choice—it comes down to how your brain is wired to process information and make decisions. So whether you outline or pants, you plot.

Okay so while Shawn designed Story Grid tools to assess an existing draft to determine if it works, and if not, identify why so we can fix it, the tools are tied directly to fundamental storytelling principles so we can use them to generate a draft as well. But just like Shawn always says, if the story is working you don’t need the tools. So when it comes to plotting, if you’re flowing in your process don’t stop – just follow your story intuition as far as it takes you. And if you find you get stuck in “what happens next?”, then you can look at your SG tools for clues to the best fit answer.

Personally, I am an outliner, so here is the gist of my process and how I use SG tools plot.

- I always start with what I know about the story – this could be characters, settings, events, or thematic concepts. I write this down in a sort of summary/synopsis like way until I have exhausted what’s in my head.

- My goal is to have a global scene list before I draft, so based on what I know, I look at what I’m missing. Do I have a beginning? A middle? An ending? I usually start out with a really clear BH, a vague ending, and a “WFT is going to happen?!”middle. So that’s where I apply SG tools – to help me figure out what needs to happen in those parts of the story.

- From Taking Ground Your craft course and editing the Four Core Fiction anthology, my understanding of Core Events has really leveled up, so based on my BH, I can find which genre’s Four Core Framework best fits the heart of my story. This gives me the Core Event in the EP that I’m building toward.

- From here, I expand to the Editor’s Six Core Questions, and use my genre’s Conventions & Obligatory Scenes and Character’s Objects of Desire to map out the middle, as well as looking at archetypal story structure like The Hero’s Journey or Virgin’s Promise for the linear progression of events. What is my protagonist’s All Is Lost moment? What is the major event that shifts the story at the midpoint?

- And as I build my global scene list to a point that feels complete enough to draft, I am consciously thinking about my POV/ND and how that affects narrative drive (thank you Leslie and Valerie for that!). For me, as someone who tends to get too linear and plots every moment, this helps me identify scenes/events that I can omit, and either leave out completely or simply reference in another scene.

For me, plotting boils down to two fundamental questions: What do I need to know to keep writing, and what does my reader need to know to keep reading. I hope that’s a useful introduction for your Su! Thank you so much for your question.

Join us next time when Leslie will look at Point of View and Narrative Device in the 1975 novel Ragtime by E.L. Doctorow and the 1981 film adaptation directed by Miloš Forman. Why not give it a read or viewing during the week, and follow along with us?

Your Roundtable Story Grid Editors are Valerie Francis, Kim Kessler, and Leslie Watts.