In my last two posts about nonfiction storytelling, we first broke down the types of story we see, use, and analyze every day, then began to break down the barriers of resistance that keep us from telling our own stories. In both, we dug into the idea that story is innate in us—a deeply felt way of helping each other survive and thrive. And in both, I proposed our collective obligation to 1) be critical of the stories we receive, and 2) be generous with the stories we share.

Before I deliver on the big promise of the title here—the nonfiction storytelling commandments that can help us tell those stories—I have to pause for a moment and deliver on my own “ask” from the last one: I have to show up on the page.

I desperately wanted these posts to be a formal series. But the topics themselves were so loud in my brain, that shifting topics to fit a series wouldn’t do. They are ideas that had sparked at the Nonfiction Seminar and that came pouring out of my mouth on speakerphone with Kim Kessler for a fair amount of my eight-hour drive home from Nashville, grateful for our time difference and her shared passion. My poor family did not process my rantings quite so well, though they did tolerate them. They are topics that I’ve put into action with a diverse range of clients in the months since.

They were the topics I had to write about before any others, and I couldn’t make the series work.

Narrative device? Resistance? Commandments? What could really tie them together? Should I shift the topics? How could I make anything as cool as what the other editors have contributed? WHAT AM I DOING HERE AT ALL?

Resistance and over-analysis escalated until, for the last twenty-four hours, I stared at the wall of resistance between me and this screen, completely blocked on how to share what comes next.

Don’t get me wrong. The post had been written. I’ve used it with clients, both verbally and in writing. I’ve lived it out as a writer and editor. I know it can be helpful. And I could not bring myself to share it.

After roughly 5,000 words admonishing others to share what they have to give, I couldn’t even open my draft document to get started.

I won’t dump my own thought gremlins in your lap, but I will say that this is not easy work that we’re doing. And this stage is often where we get locked up, tuck all of our research and experience and ideas away, and carry on with our story untold.

This is mechanization, and it’s a pill.

…and that’s when the lightbulb went off.

In my comparison to other contributors, I lost the thread of what I actually have to share. In the mire of over-analysis, I complicated the most basic forms of nonfiction storytelling: Analyze. Formalize. Mechanize.

But because story is in us, I’d done it anyway. First, I analyzed the idea of story as a necessary tool for everyone, not just the gifted few. Then I formalized ways to access the story you have to tell, via the specific lens of Big Idea. Now all that’s left is to mechanize the story frameworks that best make it happen.

Condensing Story Grid Nonfiction Theory

Recently, a brilliant Big Idea client of mine asked if there was any way we could turn the stacks of information about nonfiction story theory into something tangible. Could I just give him some bullets to follow? Something he could map out into an assignment and knock out of the ballpark?

The answer was yes, but only if I could color code it.

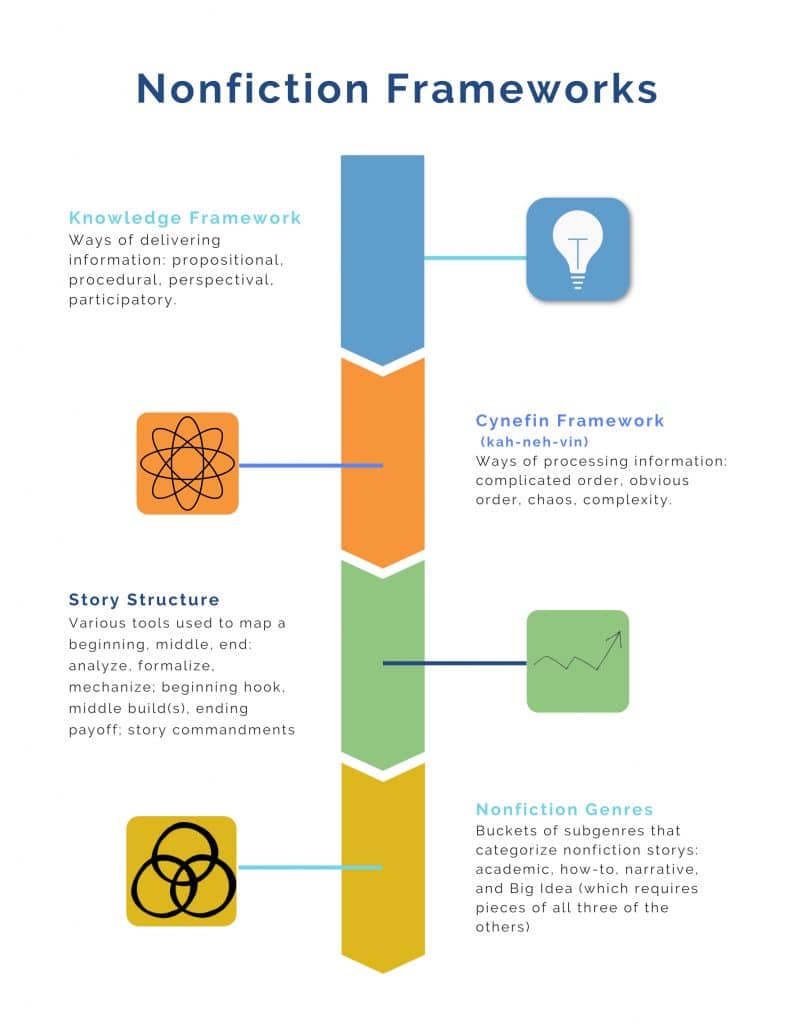

We already have the Venn diagram of our nonfiction genres—academic, how-to, narrative, and Big Idea as the combination of all three. But how do we actually compile our content to serve those genres?

Shawn put together some fantastic overlaid graphs and charts and spirals and deeper explanations (that I do recommend accessing in the seminar if you haven’t already). But for visual learners who just need a step by step Cliff’s Notes version, we’re going to simplify the overlay of multiple frameworks that all point to one thing: changing the way a person thinks.

They are the knowledge framework, the cynefin* framework, and story structure. Each is connected to the way nonfiction stories are analyzed (broken down, picked apart, and assessed), formalized (restructured in a new way), and mechanized (brought to life).

*Listen, it’s a Welsh word and not at all pronounced how it’s spelled. It means habitat and is a sense-making framework from the tech world.

- Knowledge framework: these refer to the way we present knowledge

- Propositional knowledge

- Procedural knowledge

- Perspectival knowledge

- Participatory knowledge

- Cynefin framework: these refer to the way humans (readers) experience new knowledge

- Complicated order/analysis/governing constraints

- Obvious order/categorization/fixed constraints

- Chaos/actions/no constraints

- Complexity/sensemaking/enabling constraints

- Story structure: these are how we impart knowledge in story form

- Globally:

- Beginning hook

- Middle build 1

- Middle build 2

- Ending payoff

- The five nonfiction storytelling commandments: these are still the inciting incident, progressive complications, turning point, crisis, climax, and resolution. Shawn describes them for nonfiction as something like this:

- An unexpected drop-in event complicates the reader’s existing “order”

- We continue to disturb that order until it becomes chaos—the reader can no longer return to their previous state or belief

- Then the concept is reconstructed until it turns to a new order

- We proof-test the reordered concept against our context/environment

- The change/concept interacts and integrates with the world in a way that leads them closer to or further away from their target—the reader has resolved that concept and is ready to move forward, for better or for worse, toward the next thing

- Globally:

You could take any one of these frameworks and develop a foolscap for your nonfiction book that would probably work. If something in here has already sparked your interest—take it and run. Come back to the tools when you need another boost. But if you want to watch something wild, hang on for another section.

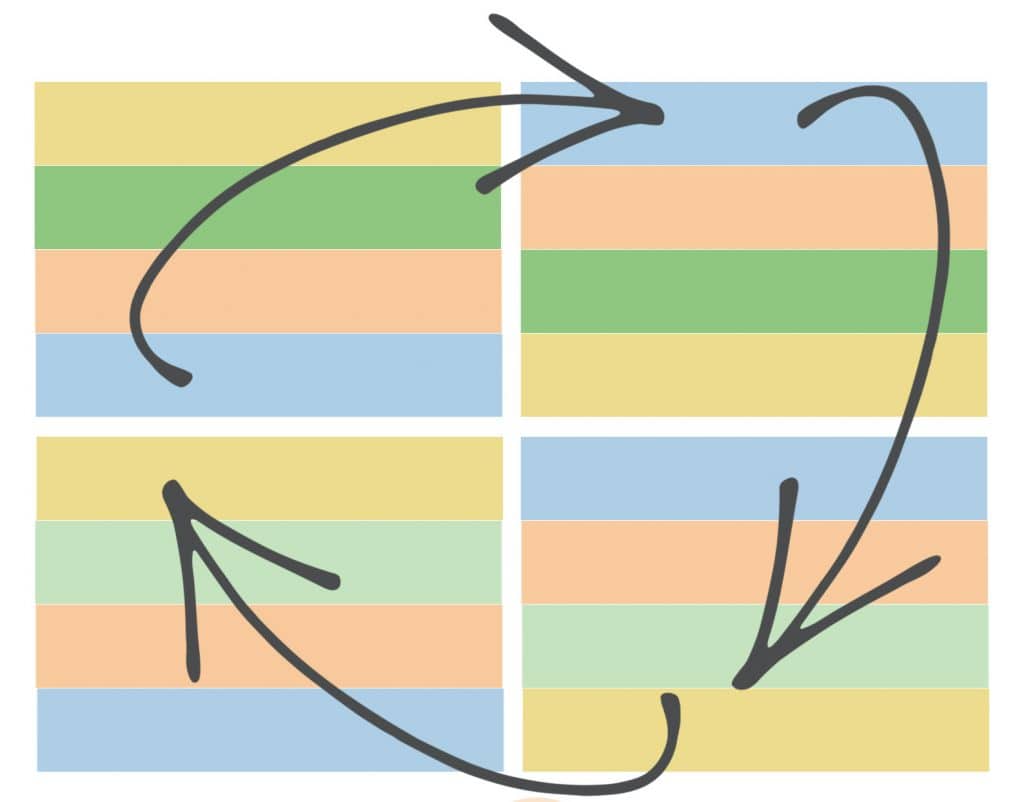

Four Quadrants of Nonfiction Storytelling

Each of the nonfiction storytelling commandments serves to move the reader through the knowledge and cynefin frameworks, because those quadrants describe how humans accept new knowledge. It’s how we give and take information that can ultimately change us. And the goal of nonfiction is to present the reader with a change you’re experiencing as the author-protagonist or that you invite the reader-protagonist to, stemming from your existing place of experience.

Without someone changing (at least their mind!), you’ve missed the plot.

So here’s where the magic happens. Because these frameworks are all about presenting, experiencing, and imparting knowledge, and they’re all based on four quadrants—we can stack them all together. We can be mindful of each of them as needed to help us add the depth that makes Big Idea so intriguing.

Stacked together, using the same color coding as above, nonfiction storytelling might break down into these compiled quadrants:

- We propose something the reader didn’t expect—a problem, theory, possibility, etc.—which complicates their current way of thinking. This proposition should be validated so much that they can’t unsee it, and are tipped into chaos.

- The reader needs something to anchor them in their chaos, so we reconstruct the initial problem into a procedure that can be considered a new, obvious order. Now they can’t go back to their old way of seeing the world—yours makes too much sense.

- Our theories are nice, but our brains need to see action to believe it’s possible. The perspective of someone who has proof-tested the reordered concept in real life gives the reader confidence that anything is possible. They have no constraints of disbelief or doubt that your theory is right and worth applying.

- The reader is now ready to step into their world with this new, complex perspective. Sensemaking feels like resolution, but as we know, resolution often tips us into the next inciting incident. As we participate together in this integrated view of the world, the reader steps out with the enabling constraints of your proven concept, which will equip them to face the one that inevitably comes next.

Do you see the nonfiction storytelling commandments layered in there (in green)? There are still five storytelling commandments, but I like to simplify it (goodness knows we deserve some simplification at this stage). Why? Because your propositional stage should be proven enough to make them care about the order you’re going to create.

Here’s my quick case for keeping the layered quadrants in mind: it gives you clear intention for every piece of your book. And distilled all the way down to four nonfiction storytelling commandments, it simplifies everything:

- Propose and prove a concept

- Make order/sense of that concept

- Demonstrate that concept in action

- Equip the reader to integrate the concept/order into their lives

I’m willing to bet everyone reading this has at least one topic on deck they could align to those four movements of thought. All that’s left is to figure out how you want weight your Big Idea or other nonfiction book to relay that topic.

Converting the Quadrants to Genre

There’s one more layer that I’ve found incredibly helpful in practice, which is that each of the quadrants also align with a type of nonfiction. For simplicity, I like to focus most on the knowledge types, because it’s simplest and most obviously connected with our goal (to impart knowledge/change how someone thinks):

- Academic = Propositional

- How-to = Procedural

- Narrative = Perspectival

- Big Idea = Participatory

A book that’s strictly academic will remain heavily propositional throughout, rarely giving any kind of how-to steps or personal narration to soften the reception—fellow academics will follow their thought pattern, and they don’t need to appeal to anyone else.

A book that’s strictly how-to might sprinkle in some personal anecdotes or a little bit of propositional theory, but for the most part the reader already knows they want to learn the procedure the author is offering. The need and result are already established, and the procedure to get there is what matters.

Direct memoir might have an indirect invitation for the reader to learn the lessons that the author learned in their lifetime, but won’t typically make that invitation explicit. It’s the author vulnerably sharing their perspectival experience, and allowing the reader to do with it what they will.

For each of these three, we’ve either changed our way of thinking by seeking out the book or aren’t required to change in order to accept what the book offers. Big Idea is an invitation to explore a new way of thinking, which requires the entire block of sensemaking quadrants.

I love this explanation from Shawn in an early podcast on the topic of nonfiction:

“…Big Idea Books are about getting to the essence of a phenomena so that they can help us solve problems. Not give us the answer but to help us get a little bit better at dealing with the phenomena that we face every single day…It’s about going on this journey of discovery with the author, where a how-to book is like, ‘I figured something out. I’m now going to tell you how to do it.’ You’re not going on the journey with the square foot gardening guy.”

The journey is the key, and the tools are how we help the reader keep up with us along that journey.

When in Doubt: Analyze, Formalize, Mechanize

If you have made it this far and your head is spinning, keep in mind that the quadrants are the underlying supports of the narrative rather than a top down requirement. So let’s take it all the way back down to the basics.

- You’ve got a story to tell. We all do. Story is how we survived in the beginning, and it’s how we thrive today.

- Story mirrors the first projectile weapon: craft it well, measure the arc, and send it off to the heart of your target reader.

- That arc has a beginning (where you are), middle (the ground it has to cover), and end (what you’re aiming for).

- Analysis helps us understand the beginning point

- Formalization covers the hang ups, issues, concerns, missing knowledge, and lack of skills in between the beginning point and end state

- Mechanization is what we do now that the arrow has landed and we can’t go back to how we once were

The Beginning Hook: Analyze

Here, you’re using the quadrants to lay out your proposition/Big Idea. You’re convincing them that where they are now (the starting point life value) is a negative, even if it’s masking as a positive. You’re proposing the idea that where they need to be (the ending life value) is the highest good. The genre term for it is academic, but that doesn’t mean you’re making a boring white pager. It just means you’re in the proving stage.

Some books will need more time in analysis than others. All Big Idea books will benefit from all four quadrants to make the analysis stick.

The Middle Build: Formalize

Again, some books have more ground to cover than others. Depending on the weight of your Big Idea, you may need to spend the bulk of the book formalizing the idea you’re laying out for them. Keep your target life values in mind, as well as a very clear target reader—what do they need to know before they can integrate the idea that you’ve invited them to accept?

I love the framing of two middle builds (especially since it aligns with this lovely model of stacked quadrants we’re working with):

Middle Build 1 is the beginning of order. It’s where you can start to give them wins—they’re in chaos now and need something to grab onto. It won’t be insight yet because they’re not ready, but at least their reactivity will be smoother, and hey maybe they’ll even get proactive here and there. Now they think they’ve got it.

Middle Build 2 moves them closer to the end, which is when they’re going to realize uh-oh, I have to actualize this. Order has to be less obvious here, because the world is complex. They have to experience the shift vicariously through someone else’s perspective, otherwise a) fear will keep them from ever taking action, or b) they’ll take action on your half-baked how-to without any constraints, crash and burn, and blame you for it.

On the surface, you could still give a lot of weight to procedural/how-tos in both sections, but as you wind down the middle build, you’re pressing them to go further than just consuming information. You’re asking them to accept a new reality and to start to see it playing out in their own context. Perspectival shifts give them reason to believe it’s possible.

The Ending Payoff: Mechanize

Here’s where your reader can accept the complexity of a world where your Big Idea is true. You’ve invited them to think about the world differently so that they can better solve their problems, and they’re ready to re-enter their world with a fresh perspective and new tools.

Every resolution is an inciting incident, and this is their inciting incident for life after the book. For the nonfiction author who isn’t a journalist or career author, that inciting incident might mean the reader reaching out to you, inviting you to speak, craving a follow up book, or whatever your goals for that book might be. They should be ready at this point to integrate your Big Idea (the proposition you set up in the beginning hook) and participate in your world with you.

Because the frameworks underlying all of this are still just about how we present and integrate to new information, your reader should take that journey for every section, every chapter, every part, and the whole book. It’s how they buy in.

Here’s a simple chapter outline condensed from all of that:

- Hook with a depiction or exposition of problem statement, then back it up with why you know that problem is real

- Lay out the solution for that problem

- Show someone living out the solution, real or hypothetical (as long as it feels real via narration)

- Depict the better world that the reader will live in because of that solution

Commandments on Scene and Beat Levels

Now, we know that structure and form align, and the commandments that work on a global level are going to be mirrored on a scene and beat level too.

Using the quadrants as commandments gives us both structure and form to follow when determining the genre, identifying the overall controlling concept of the book, setting out the global structure, and mapping out chapters/scenes.

Again, if you have what you need to spark creativity, run. But there’s another tool here I sometimes find helpful: we can use the quadrants to help us sort out existing information into the most effective order throughout the text.

- Use academic-type information—data, statistics, anecdotal, experiential accumulated knowledge—to propose and prove a concept.

- Use how-to, instructional, procedural steps to make order/sense of the concept.

- Use real life perspective—narration, anecdotes, experiential accumulated knowledge to demonstrate the concept. (The repetition from the first line is intentional. Among other things, you can start a story in the beginning and call back to its completion here.)

- Present the participatory invitation by recalling the shift they’ve made around that concept, which prepares them to pivot toward the next concept that’s going to complicate the new order you just gave them. (In other words, have a recap/segue).

Like all of our tools for analysis and craft, you don’t have to do this. And it can get squishy, because you can reword and reframe text to tip toward any quadrant. Relay a study as a narrative, tell personal experience as academia, and give how-to information as a participatory information.

I’ve found these sorting frameworks to be incredibly helpful when I have a mess of ideas in front of me and no idea how to start untangling it into something a reader might enjoy.

Hopefully, that’s how these posts landed as well.

Keeping in mind that I did this series entirely from unconscious competence, I think a case could be made for an academic bent in the Narrative Device article, a fair amount of how-to in the Unlock Your Story article, perspectival vulnerability in the opening here, followed by an invitation to the Big Idea in the mess of color-coded content that followed. It’s not perfect, but it’s the makings of a How-to Weighted Big Idea, or at least Big Idea Lite.

What I now realize perhaps more than ever before, is that Big Idea can be the most freeing of all of the story types. For all of its complexities, it’s an invitation rather than a prescriptive or definitive take on a topic—which means you don’t have to be perfect. You don’t even have to be right. It’s an intellectual adventure. Again, quoting Shawn: “It’s the kind of book that everybody you ever meet always says is lurking in their mind.”

If that’s you, consider this my invitation to you. Pick a tool—any tool—and set your target.

Adventure awaits!

Resources

What’s the big idea?: Nonfiction Condensed

Making Big Idea Nonfiction Work

Think Big: Tackling a Big Idea Nonfiction Story