👉 Write a book you're proud to publish 👈

“Stories are just hyper-realistic microcosms of reality.” I gaped as Shawn said it, or at least something to that effect. As often happens during training events, it was a brief moment spoken and then left behind as though it was something everyone knew. And maybe most of them on that call did, but my mind was blown.

It was sometime in the middle of a week-long Zoom marathon, backing the Hero’s Journey conference right into Certified Editor training, smack in the middle of the pandemic. Honestly, that whole year felt like a microcosm of reality. It certainly wasn’t normal. With nonfiction as my niche, I wondered just how true that statement could be for the work that I do. Would anyone really want to rehash times like these in even greater, painstaking detail? On the flip side of that—do we have to have intense experiences to draw from in order to write good nonfiction?

The question stayed burrowed in the back of my brain, hiding behind my encouragements to authors to “tell your story unapologetically!” and “trust yourself—if it’s significant to you there’s someone else it’ll matter to, too!” All the while harboring my own insecurities about my own perspective and experiences and teaching.

It wasn’t until Kim Kessler had her (very) literal and essential breakthrough—because are you really working during a pandemic if you’re not on Zoom with someone for…some hours…every day?—that those stories I’d told myself started to break down. Here’s why Shawn’s statement was and is true:

Stories are explorations of truth.

When we’re writing our hyper-realistic microcosms of reality, we’re telling the whole story in a condensed space of time.

- What literally happened around us or our characters.

- How we essentially saw and responded to it based on our limited worldviews.

- And the progression of change (the “hero’s journey”) that allowed us to shift our worldview and respond in new ways to what was happening around us.

In tandem with the developing the Heroic Journey 2.0 that we started to wade into during those events, these are the three genre dimensions of story (action, worldview, Hero’s Journey) in nonfiction form: what’s happening, how we view(ed) and interpret(ed) it, and how we are invited to change.

Or, as Kim just invited us to explore: our literal wants guiding our choices, our essential needs driving that want, and the core truth we have to understand in order to break those loops.

Ready for more stacked layers of principles? I’ll try not to get too far into Always Sunny in Philadelphia territory with the layering this time. Let’s go.

Genre Interplay Between Fiction and Nonfiction

If you’ve been on a Guild call, at Story Grid Live, or in any kind of group setting where masterwork scene analysis takes place, you’ll know that genre isn’t always as obvious as it might seem. Three people in the corner say it’s a thriller, two in the back are mumbling about the worldview implications, and the outlier in the front row who is sure it’s a love story.

Honestly, you may be able to relate just based on the war in your own head. After much life-value-searching and talking it out (yes, talking it out with yourself counts), you’ll reluctantly land on one as the primary and the other as the subgenre, and maybe make a solid case for a third as an internal.

It’s not much different for nonfiction. Every now and then it’s obviously a how-to or definitely a memoir, but there’s usually a flurry of questions and doubts when it comes time to commit to a book structure using genre. What am I writing, really?

The good news for nonfiction is that we have a leg up on fiction. At least in my foray into fiction, the external/internal, primary and subgenre conversation continues to feel muddy. I can tell you what’s loudest to me, but I’m probably not going to align to the “right” way of parsing them out.

Nonfiction isn’t always that fuzzy.

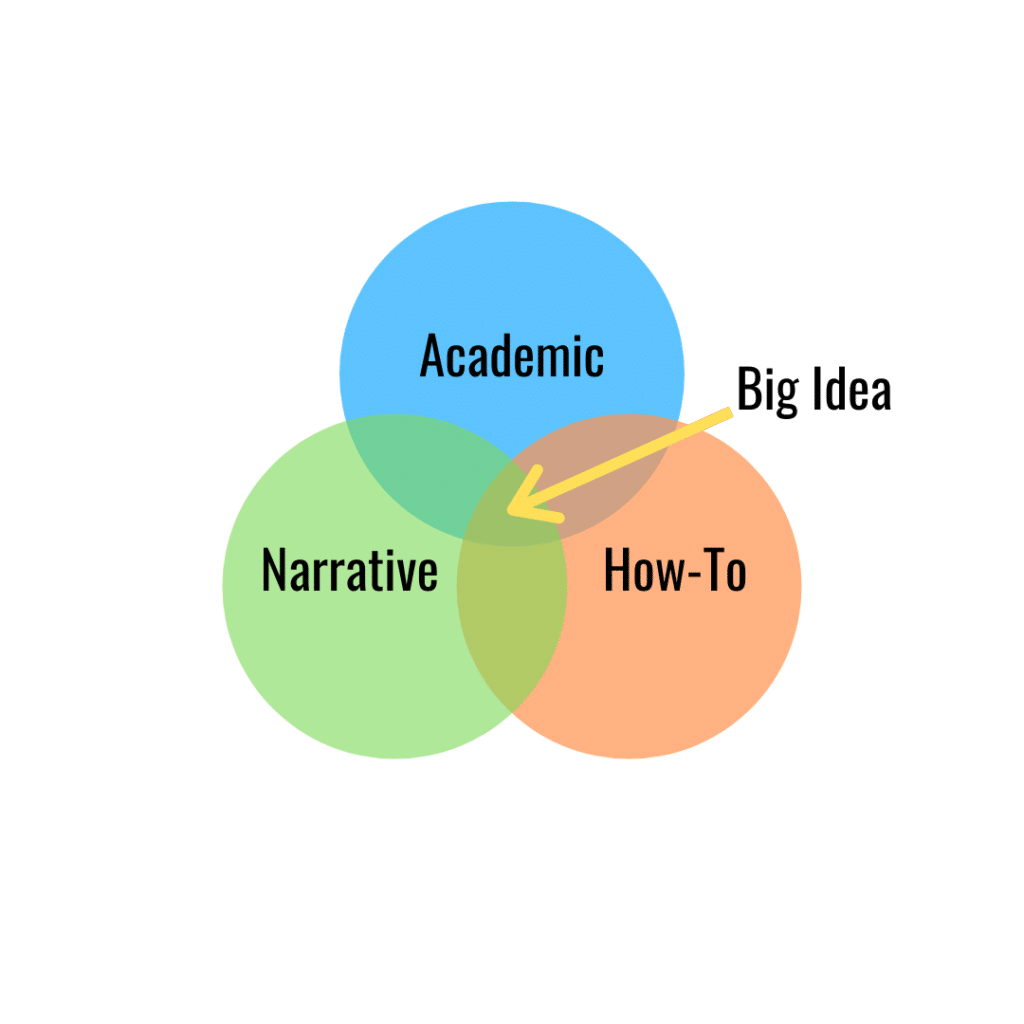

For example, we know that Big Idea Nonfiction is comprised of multiple types of genres—how-to, academic, and narrative—all rolled into one really effective package.

And we know that most Big Idea books are weighted more toward one or two of the three types instead of being perfectly balanced.

And we can even give ourselves permission to write Big Idea Lite, where we draw on the principles of Big Idea without going ham on the Gladwellian author-journalist journey.

Basically, if we know what we’re trying to deliver and are able to do so in a way that moves the reader from where they are to where we’re inviting them, we can pull from all of those facets and intersections to make our material work.

But story is story is story. So what if there is a Venn diagram for great fiction too? And what if we can pull from all of the fiction tools (like the literal and essential actions) to add depth and improve our decision-making on nonfiction as well?

Genre Dimensions and Compelling Stories

Let’s preface this by setting a quick caveat: Plenty of (monetarily) successful fiction and nonfiction books do not dig to the level we’re aspiring to here. For lots of reasons. Maybe they have an existing established audience who gobbles up everything. Maybe they hit a publisher at the right time with the right quirky niche and it took off. Maybe their readers or viewers just want a surface-level good time or a basic “self-help” pat on the back without any further challenge.

If that’s what you want to create, there is nothing wrong with that.

But I suspect you’re here because you want something more. And if you want something more, you know how challenging it can be to make “the right” decisions as you structure, restructure, and polish your book.

“How many people say ‘Lethal Weapon changed my life’?…It’s the same story with new suits.”

—Shawn Coyne, Heroic Journey 2.0

In fact, you may be someone who wants more from your story and think that those box office hits or worldwide bestsellers held the secret. But instead of drawing from what works and applying it to what you set out to write, you start using it as a template. You dilute your story, water down your voice, over-cite other works and research, and generally manufacture an imposter scenario for yourself.

No? Just me?

We see it a little easier in nonfiction, because honestly there’s not much to hide behind over on that side of the editing wall.

We already know we’re writing for a specific purpose. We often know our personal relationship to the topic. We know who our audience is and how it’s got to be limited. It’s all out there on the table, which means it’s not too hard to see where we’re withholding something of ourselves or our message.

And it’s definitely not hard to connect those hesitations to something like imposter syndrome or inauthenticity. After all, your nonfiction is you.

Fiction, I’m finding, is a whole other ballgame. It’s all too easy to believe we’re “just” writing. Just a cool idea. Just a thing I’ve always wanted to do. Just a dream I had. Just having fun…

So when structure gets funky and we choose a genre or masterwork to revise against, there’s not much stopping us from holding back our story in the name of learning from a good story.

Want to know why there are half a dozen more live action remakes coming out? It’s a good story that works. How about when a rash of action flicks comes out all of a sudden? Good enough story that works. Terribly written fan-fic-that-shall-not-be-named? Direct mimic of something that worked.

If we truly do want more, then we have to go out and find it. More accurately, we have to face it.

Not just what’s happening on the surface—which is so easily comparable against others in that same genre realm. But also what’s going on in the reader’s or character’s minds and how they see and interpret and respond to those surface level shifts. And if those under the surface level analyses are going to change, what journey do they have to go on to get there? What will take them beyond anything they knew at or under the surface and present them with their missing truth?

That feels like more than a realistic moment in time, because we don’t like to face all of those complexities at once. Our internal stories and habits and coping mechanisms protect us from much of that chaos, otherwise we’d have constant existential crises. (Or, you know…books.)

The Three Genre Dimensions All Good Stories Have

Story as a microcosm of reality means getting our hands dirty inside and outside and beyond what’s happening in a given moment.

In Big Idea nonfiction, that means we can’t just get away with dry analysis, unless we’re writing a white paper that’s only intended for our interested peers and colleagues. We can’t just write a narrative without any point, unless we’re writing for the fun of it or already have an audience gobbling it up. And we don’t really want to just write how-to stuff, unless our folks really do just want those shelf plans or recipes-without-the-backstory.

If we want to invite nonfiction readers to think differently about a topic, then we have to go inside and outside and beyond—how they think about it now, how we shifted, and how they can change too.

Taking those same Big Idea principles and layering them with those inside, outside, and beyond dimensions we explored during Heroic Journey 2.0, our fiction genre choices look less like a hierarchy and more like that Venn diagram.

The action component is what we see happening on the outside—on a surface level, what is literally going on? Are we trying to start a new nation in the face of literal and political war? Are we trying to get back home to Kansas after being swept away into a magical land?

- Nonfiction parallel: This is what I compare to the procedural, or how-to component. Why? Because your reader picked up your book for a very specific reason. They have a literal want they hope to get from their time reading, and you’d better deliver in literal ways to keep them reading. Is it the only way? Maybe not. But as a model, it tends to be helpful.

The worldview component is what’s actually going on inside—in response to the action, because of who you or your reader are, what’s essentially driving and interpreting all of that action? Are we stopping at nothing to prove ourselves because ambition is our folly? Are we learning the complexities of humans (and witches and munchkins) and coming to a more mature understanding of our family members? How do we interpret the world at the beginning vs at the end?

- Nonfiction parallel: This is the analysis piece, which we typically call academic. That’s not to say it’s all about stats and data, but rather the spirit of academia. The ethos behind the logos. Academia is all about exploring a subsection or microsection of reality for what it is and inviting challenge. It’s all about perspectives as they are. How do you see the world? How does your reader?

The heroic journey component is something beyond the literal moment. It’s the invitation and opportunity to grow and change. What will it take to shift that worldview and respond in a new way to the action around us? When faced with the core truth that we’ve been missing, will we accept it or refuse the call? Will we click our heels and go home or sneak in one last duel at dawn?

- Nonfiction parallel: This seems to mesh best with narrative. Why? Because in order to have a perspectival shift, we really do need to track with a human element. A Big Idea asks a lot of the cognitive brain, which is prone to resistance. Story that cuts right to the emotion hijacks all of that and we can’t help but listen. (Not to mention the trust building that happens when you can make this component about your journey to obtain and accept the knowledge.)

See, what’s happening on the outside often feels uncontrollable—that’s probably why a Lethal Weapon type story actually is cathartic. We get to see a hero overcome the odds and regain some control, without having to process what it actually costs us internally to do it.

And what’s happening on the inside tends to feel static. We are who we are and that’s all we are, cans of spinach or no. That’s probably why bubblegum pop psychology self-help books fly off the shelves. It feels good to be affirmed. Less good to be challenged.

A heroic journey calls us to become something more. To reexamine all of that literal and essential, external and internal, inside and outside junk under a new light. The outside action and the inside worldview may or may not change, depending on what you want to explore and create for your reader. But the heroic journey will be the catalyst for that experience.

Nonfiction tools for fiction genre dimensions:

- If choosing one or two genres feels constricting, try three instead! What is the action container that moves the story along? What kind of internal shift do you want to depict? And what kind of journey is the protagonist taking to get to their truth? (Hint: self-love is a really good start.) Nonfiction folks, this looks a lot like choosing a “weight” for your Big Idea. Do the scales tip more toward teaching a literal process, exploring and analyzing a concept, or relaying an experience?

- If you’re feeling lost trying to mirror a single masterwork, try three instead! No, that doesn’t make it more complicated. It actually lifts some of the pressure. If your action component is a Western, go find the best gunslingers out there and track with their use of movement and external conflict. If your internal worldview shift is all about education, grab a box of tissues and go watch Soul. Wanting to take a self-love journey? Keep the tissues and spend some time with Bridget Jones. You could be writing a space opera war hero saving planets book and all of those could be useful at given moments on your journey. Nonfiction folks, look for the books that teach well, change your perspective, and suck you into the narrative. When in doubt, identify which arc you need to move along and go to that masterwork for insight.

Wants and Needs in Nonfiction

Okay, nonfiction. I didn’t forget you. We have a lot to learn from fiction too. For as much as I just talked up how straightforward nonfiction is, sometimes it’s our Achilles heel. Or maybe a lot of times.

Just days after musing that every manuscript I’d seen in the first quarter of the year had two genre dimensions but lacked the third, a client called me out for the same exact thing in a document I created for him. And I had been so proud of myself for being thorough.

The problem wasn’t my lack of understanding on the topic (though that has certainly happened before). It wasn’t that I wasn’t passionate about or connected to what I’d written (though we are not going to recount all of the dry miserable content I’ve ever mocked up). It wasn’t even that I had the wrong audience.

I’d attempted to hit all of the points of the journey. My Venn diagram was lighting. up.

And I still completely missed my reader.

Why? Because I didn’t slow down enough to bring his wants and his needs into the picture.

In the same way that fiction writers need to understand what their characters literally and essentially want and need before they can map out a meaningful journey for them—we also have to understand our readers.

Some of that understanding should shape genre weighting overall. If your reader is stressed out and working 70-hour weeks, how likely are they to absorb your six-figure word count memoir? If your reader is heavily resistant to change, how much stock will they place in your step by step procedure?

That seems to be true for fiction as well. People gravitate toward certain story types for a reason, and understanding those reasons can help you choose a container that will appeal to the reader who will get the most out of the journey.

But it goes deeper, too. This is about how we present information and stories in a way that engages and moves our readers. Which means we’re making those choices around every new corner of the content.

Yes, Rachel Carson wanted to dig into the science and change detrimental practices. But her reader just wanted to continue living their lives unbothered. She had to deliver on that want—her academia had to be laced with narrative that told the reader how to get or keep what they wanted.

Yes, Lin Manuel Miranda wanted to tell the story of a founding father that deeply resonated with him. But the viewers he had in mind weren’t reading that book and certainly weren’t moved that much by it. He had to lace the narrative with a relatable worldview and flavors of modern day analysis in order to bring us into that space.

Yes, I was very proud of my document—and it has even worked in some other scenarios. But my client wanted something different. Even if that document was exactly what I knew he needed, it wouldn’t matter if it didn’t have enough of what he wanted to make him stick around and find that missing truth. I had to shift the framing and presentation so that he got what he wanted before he could accept the need.

Fiction wants/needs tools to sharpen nonfiction delivery:

- As with fiction, your reader’s wants are likely to be conscious (and very loud), while the need may be unconscious or masked. If you’re working with business nonfiction or relaying some kind of process that you’ve put into play before, think back to what people say they’re hoping to achieve when they first come to you. If this is a new exploration, think about what got you interested in the first place. Think about how and why other people are in this space. These are likely your wants. The need is closer to the thing you have to break to them gently, or the realization you had a while down the road.

- Next is identifying the core missing truth—which is really fun. Why is it that no one else has solved this for them? What are they missing that keeps them from spinning out at the want and never satisfying the need?

Wants: to verb [specific content].

Needs: to verb [specific content].

But unless they realize [specific missing truth], they will never be able to [specific content].

Credit to Kim Kessler

Bringing It All Together to Unlock Your Story

Now you’ve named the reader’s wants and can bring them along throughout the text, you’ve built toward surfacing and meeting their need so that they quit trying all the wrong things to get what they want, and you’ve dug all the way down to the root of a missing truth that’s going to change their perspective and make this book be the one that sticks.

That means you’ve essentially tapped into the LV – the life value shift of the book. Ignorance to wisdom, naïve to sophisticated, helpless to empowered…And by naming all of these components, you’ll be able to validate or rehash your genre choices from the previous section, and around and around we go until something unlocks and the story truly, actually, powerfully works.

If you’re still feeling stuck, know that it’s okay to not have all the answers right now. Sometimes all we need is a starting point (especially if you’re an overachiever in here plucking editing tools while you’re still trying to draft…I see you. I…may be you).

You don’t have to follow all the models—you just need to find the one that will unlock the door you’re stuck at right now.

You don’t have to squeeze your story into a genre box—you just need to find the genre tools that will highlight the journey your characters or concepts are on.

And I’ll repeat it because it’s important: you don’t have to have all of the answers right now (or ever). You just have to be willing to take one more step in the direction of the story that wants to be told.

Here’s a quick method you can use to find an “in” on nonfiction:

- What does your reader primarily need?

- If it’s a process—they’re ready and eager to follow steps toward an outcome—focus on your how-to material and that external/action driven approach.

- If it’s an understanding—they don’t see what you see and need to get closer to the topic to really be able to grow—start with analysis. And don’t forget to bring yourself into that analysis! Focus on why and how you learned the thing, not just the data itself.

- If it’s a perspective shift—if you really find yourself working toward mindset changes or completely different ways of viewing the world—you’re going to need story. Find the stories that really demonstrate the hardest parts of the change and the best that’s waiting on the other side.

You will, of course, need at least some of all three components, but starting there will give you a solid spine to build out from.

Similarly for fiction:

- What life value shift do you hope to demonstrate in your story?

- What external genre choices could help you create the action that will challenge that life value?

- What does your protagonist’s worldview perspective look like at the beginning and the end?

- How are they responding to their external circumstances?

- How are they limited by those responses?

- What journey is your protagonist on (and, if we can pry a bit like we do for nonfic: why are you exploring that journey?) toward their core truth? Are they going to shift when presented with it or double down?

This is the hyperrealism that we get to create with story. Not just the technicolor shift when Kansas falls away, but the cold light of day that hits us when those old tapes and mental stories are hijacked.

If you can do that with your content, who cares what blockbuster we’re spacing out to these days. You’re going to change people with that kind of work, and changed people change the world. Even if it is just a microcosm of it.