The Case for Analyzing Masterworks, Part II

Washington Crossing the Delaware, Emanuel Leutze (American, Schwäbisch Gmünd 1816–1868 Washington, D.C.)

All right, fellow Story Grid nerds. Time for some tough talk. (We’re serious writers. We can handle it.)

Shawn Coyne tells us to “study masterworks.”

How many of you have actually gone out and done it? How many of you have taken a masterwork in your genre and given it the Story Grid treatment, right down to the spreadsheet and the graph?

And if not—why not? After all, we know that it’s important. It’s explained in the Story Grid book, and Shawn goes into various examples of masterworks on many episodes of the podcast. And Tim Grahl, Shawn’s Story Grid podcast partner, has done it also (Tim did the Story Grid spreadsheet for the first Harry Potter volume although he didn’t do the graph, but he still has the polarity shifts, which is what the graph is, after all).

But…ugh. Here’s the truth. It’s a boatload of work. And it’s not even OUR work. Because we have to do the spreadsheet and graph for our own work eventually, right? So the last thing we want to think about is going through all of that for someone else’s book.

It’s a tough demand for a struggling author. And many of us can’t find the time, are afraid of the task, or refuse to believe that it makes sense to analyze books other than our own, so we don’t do it.

In this article, I’m going to explain why it’s so important for you to dissect the masterworks in your genre and to apply the Story Grid treatment to your favorite authors before you attempt it on your own work. In addition, I’m going to show you a little snippet from a book that I’ve spreadsheeted and graphed. I’m hoping that I will be able to convince you to take the time and trouble, because the full-scale application of the Story Grid treatment will not only improve your skills as a writer, but it can also shorten the timeline on your writing projects if you are looking for a way to “game” Nanowrimo or to plot or storyboard your next project quickly. And last, I’ll show you a quick-and-dirty method that I’ve developed that isn’t a full Story Grid analysis by any means, but will serve as a method by which you can use a masterwork to either “check” your work or plan a new project.

The Annunciation, Botticelli (Alessandro di Mariano Filipepi) (Italian, Florence 1444/45–1510 Florence)

Why you should do this

Masterworks, in Story Grid parlance, are books that are noted examples of the genre. In Story Grid, Shawn Coyne uses The Silence of the Lambs as an example of a well-executed thriller which uses an internal worldview disillusionment plot to create a complex page-turner. He provides a complete spreadsheet and Story Grid graph so that the reader can see the bare-bones structure behind a brilliantly satisfying read.

But Story Grid was developed as an analytical tool. Analysis, after all, is destructive, not creative. One does not analyze if one is trying to create; rather, one must “synthesize.”

How do we use Story Grid analysis in order to help us create our own work of genius? How do you engage in a destructive activity like analysis at the same time that you are supposed to be synthesizing?

This, my friends, is the million-dollar question, because trying to Story Grid your own work while you create it is like being at war with yourself. Which, in essence, you are. Taking your words and boiling them down to dots on a graph is painful—but that’s how the reader receives it, after all. The experience of a story can be reduced to: emotion up, emotion down, becoming more and more intense over the course of the story journey. This is how you define a page-turner. And if we analyze as we write, we are simultaneously the giver and receiver of the experience. It’s enough to drive anyone crazy.

We know the result that we want: the story that works. We know what it looks like, because we’re readers, and we can think of lots of examples of books that work. And with Story Grid, we know why they work.

The middle ground between Story Grid and our novels lies in studying masterworks and using them as guides. The goal is to internalize these successful stories, their cadences and trajectories, so that we can aim to please our audience in that “surprising but inevitable” way.

It’s not easy, and it’s not fun. However, neither is algebra or grammar. The teachers who told you learning was “fun?” They lied. It’s not. Learning involves hard work, sweat equity, and high levels of frustration. If you’re pissed at your work-in-progress—you’re probably doing it right.

So let’s take a step backwards from our own work, and look at something that we already know is good. This is a lot easier than trying to be the reader and the writer at the same time. It’s still hard, but it’s one step removed from trying to pretend that we can be objective about our own work. What’s more, our own draft-in-progress might not be ready for the Story Grid treatment yet. Let’s spend the time examining something that we are sure already works.

I’m also going to recommend that you analyze actual books. This recommendation is probably eliciting groans far and wide. Yes, it takes a long time to read an entire book. Yes, it takes an even longer time to ponder each and every scene. I’ve never met a writer who says she has more time than she knows what to do with, so I understand if this sounds impossible. However, while it is possible to apply Story Grid principles to movies, knock-knock jokes, commercials, and even choreography and music, the way in which it will best serve YOU, the writer, is in its application to the written word. Applying Story Grid principles to, let’s say, a commercial, is best done in the macro sense. Are the five commandments there, for example? What genre is it in? But at the micro level, there isn’t a lot there to help the novelist. Analyzing point-of-view for the visual medium gets complicated, for example. And what we want is to help the writer turn those scenes and deliver the effect that will, in the aggregate, result in a satisfying story well told. The best way in which to do this is to dive deep into the words of an author whose work you admire.

Hermann von Wedigh III, Hans Holbein the Younger (German, Augsburg 1497/98–1543 London)

An example: Frankenstein

Earlier this year, I completed a full analysis of Frankenstein. As I mentioned in my last blog post, I am no fan of the horror genre. But when I thought about choosing a masterwork to analyze, I wanted to pick something that has stood the test of time. I also wanted to look at something exciting and dramatic, not a staid, prim example of “literature.” And I already knew I enjoyed other period favorites, such as Wuthering Heights. Looking at a book from the point of view of Story Grid is quite a different experience from reading it and enjoying it. This is why I suggest choosing a genre that you love or a book that you know well.

An entire novel can be explained using the structure of the Foolscap Story Grid. However, the questions that we address using the Foolscap are big, macro questions. I recommend that you save this task for later. Why? Because despite how it may appear, this is actually a difficult task to pull off well unless you have already examined the individual scenes in the novel. As you work on the micro-level analysis of your masterwork, you will start to see the answers to the big questions on the Foolscap.

This means building a Story Grid spreadsheet, which you may use later to find the individual scenes that form the conventions and obligatory scenes of the genre, as well as the building blocks (five commandments) that make up the beginning hook, middle build, and ending payoff of the entire novel. It’s much easier to find all of those pieces if you are looking at a deconstructed whole laid out on a spreadsheet.

There are many iterations of the Story Grid spreadsheet; Tim is working on a spreadsheet for his own work-in-progress at the moment, as he discusses with Shawn in this episode of the Story Grid Podcast. There is the “basic” format as outlined in The Story Grid book, as well as Shawn’s “Ph.D. version” (mentioned in the same podcast episode above). Story Grid editor Anne Hawley has also designed an alternative version that includes extra columns meant to track opening and closing lines, the five commandments, conflict type, etc. When you eventually get around to putting your own novel on the Story Grid spreadsheet, you may want to extend your analysis by adding additional columns. This will help you to refine your writing. But for now, as you examine your masterwork, you can stick with the basic version here. It will be enough.

Because I have an inherent dislike of spreadsheets (I acknowledge they are useful, but they scramble my brain because they’re so ugly!), I started out my micro analysis of Frankenstein in exactly the same way that Shawn analyzes Pride and Prejudice: I split the book up into scenes and asked myself what was going on in each scene. I did this with narrative (i.e. I wrote paragraphs to explain to myself why I made the choices I did) in order to fight my spreadsheet aversion!

I’m assuming that most Story Grid fans know the basic premise of Frankenstein: young Victor Frankenstein builds a grotesque monster and animates it. I will try not to reveal any spoilers here!

Let’s take a look at one of the early pivotal scenes in the book. In Chapter 3 (scene 10 on my spreadsheet), Victor Frankenstein arrives at university after leaving home and family for the first time.

- What are the characters literally doing in this scene? Victor has arrived at university and met the two principal science professors.

- What is the essential action of what the characters are doing in this scene? For a great explanation and deep dive into “essential action,” Story Grid editors Leslie Watts and Anne Hawley have a great article on the Story Grid website on the subject. Briefly, the essential action underlies the literal action. It’s the subtext. In this scene, Frankenstein is looking for his purpose in life. On the surface, he’s meeting professors, but underneath, he’s searching for meaning.

- What life value has changed? What life value do I highlight on my spreadsheet? This is a horror novel, so we need to keep in mind the fact that the global value at stake in a horror novel is Life to Death (and beyond, to “Death would be a mercy”). The scene’s value should relate back to the global value at stake. I chose to highlight “disinterested to obsessive.” When I think of “life force,” I think of lassitude versus energy, and that is what I see here in this scene. Frankenstein starts out melancholy and almost bored, and ends the scene with energy that is beyond “interested.”

I then listed the five commandments of storytelling for this scene:

- Inciting Incident: Frankenstein arrives at university and visits Professor Krempe, who teaches natural philosophy (science).

- Progressive Complication: Krempe mocks Frankenstein when he hears that Frankenstein’s formative academic influences include Magnus and Paracelsus.

- Crisis: Frankenstein attends a lecture by Professor Waldman, a teacher of chemistry recommended by Krempe; he is staggered at the pronouncements of Waldman about the possibilities of modern science.

- Climax: Best bad choice. Frankenstein, who had been bored and disgusted by Krempe’s “repulsive countenance” and massive ego, had not expected to be enthralled by modern science. However, after Waldman’s lecture he resolves to return to his “ancient studies” as part of a determination to discover the mysteries of creation, even if it means putting up with Krempe.

- Resolution: Frankenstein visits Waldman and asks to become his disciple.

This is a critical scene. At first glance, it may not appear so, but when you examine what is going on at this detailed level, you can see what Mary Shelley is doing. First of all, we have Frankenstein arriving at university. He has never been away from home and his mother has just died. We don’t expect him to be happily carousing with his new friends, but being insulted and mocked by your new professor is a pretty horrible reception indeed! Professor Krempe humiliates Frankenstein, who responds rudely. Shelley goes out of her way to make Krempe ugly, just to drive her point home. Then Frankenstein meets Professor Waldman—who happens to be handsome and has a voice “the sweetest I had ever heard.” In the middle of Waldman’s lecture, Frankenstein then says, “…I felt as if my soul were grappling with a palpable enemy.” He decides that he is going to use science to search for the “deepest mysteries of creation.”

Later, when Frankenstein is describing this event to the narrator of the book, he characterizes it as the moment where things went wrong. And when we examine the details, we can see that Shelley uses several blunt instruments to drive her point home. She makes Krempe ugly and Waldman handsome; she kills off Frankenstein’s mother before he arrives at university so that he is morose and lethargic; she has Frankenstein’s new advisor mock and humiliate him, only to have him rescued by another science professor who is kind. Frankenstein is in a vulnerable state when he arrives at university, and Shelley jerks him around psychologically, preparing the ground so that his obsession with science and the origins of life make sense for him in his specific circumstances.

This scene is filled with examples of value shifts: lonely to even lonelier, humble to arrogant, disinterested to passionate. It’s a powerful scene all by itself, and in a non-horror novel it might even be somewhat cartoonish. But because the scope of the novel has to reach the depths of despair, it works, and gives you the sense of foreboding that you need in order to keep turning pages, as Frankenstein descends into an ever-deeper pit.

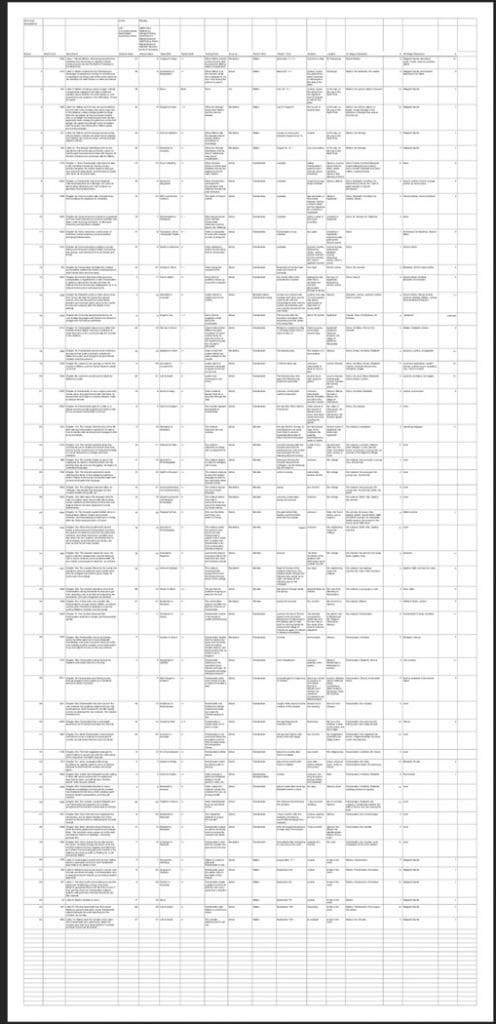

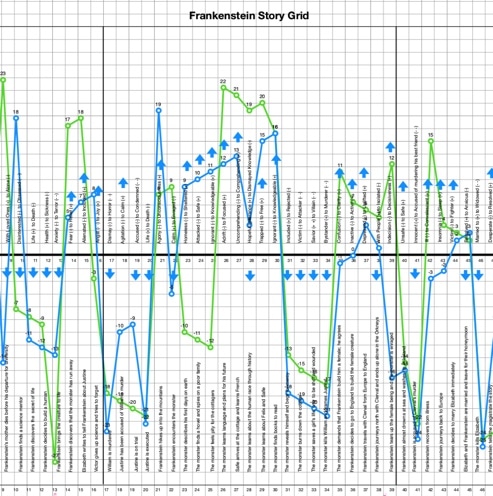

A mini version of the Frankenstein spreadsheet; it really isn’t as scary as you may think!

Scene by scene, I went through the entire book. After writing it all out in narrative style, I then opened a blank copy of the Story Grid spreadsheet and went to town. Because I had already gone through every scene, the initial entries were easy to complete (scene number, story event, value shift, etc.). Some of the other entries involved some tedious examination (on- and off-stage characters, for instance) but they didn’t involve any actual thinking, which actually turned out to be a relief!

A snippet from the middle build of the spreadsheet.

When I was done, I was able to create a Story Grid graph by positioning each scene against every other scene in the novel (I used numbers, but you can be more free-form as you graph, if you wish). I could see the effects of the micro value shifts on the macro story as a whole. At that point, I knew that if I ever wanted to write a powerful horror novel, I could use Mary Shelley’s techniques to make sure that my scenes turned. I could also examine the way in which she ordered her scenes so as to deliver the most exciting journey possible for my reader. I had created a template of sorts that I could drop on top of my writing to see if I was creating a journey anywhere near as exciting as that of Frankenstein.

Joséphine-Éléonore-Marie-Pauline de Galard de Brassac de Béarn (1825–1860), Princesse de Broglie, Jean Auguste Dominique Ingres (French, Montauban 1780–1867 Paris)

A quick-and-dirty game plan for masterwork analysis

I know that even with the above argument and lots of encouragement, you aren’t going to want to spreadsheet a masterwork. It takes a long time, it makes your head hurt, and it also can be discouraging. Mary Shelley was only twenty-one when she published Frankenstein, which she had been working on for about two years. I’m just a little older than she was (cough). Where’s my blockbuster novel? How did she think of all these scene-turning devices, and then lay them out in just the right way?

- Step one. Find a novel that is as close as you can get to your own work. Look for the right genre, the right length, and the right emotional “temperature” and pacing. In other words, don’t use a spicy romance for a sweet romance, and don’t use a slow-and-steady historical novel if you’re writing a historical that focuses on a single exciting battle. Choose something that you love to read and would love to emulate.

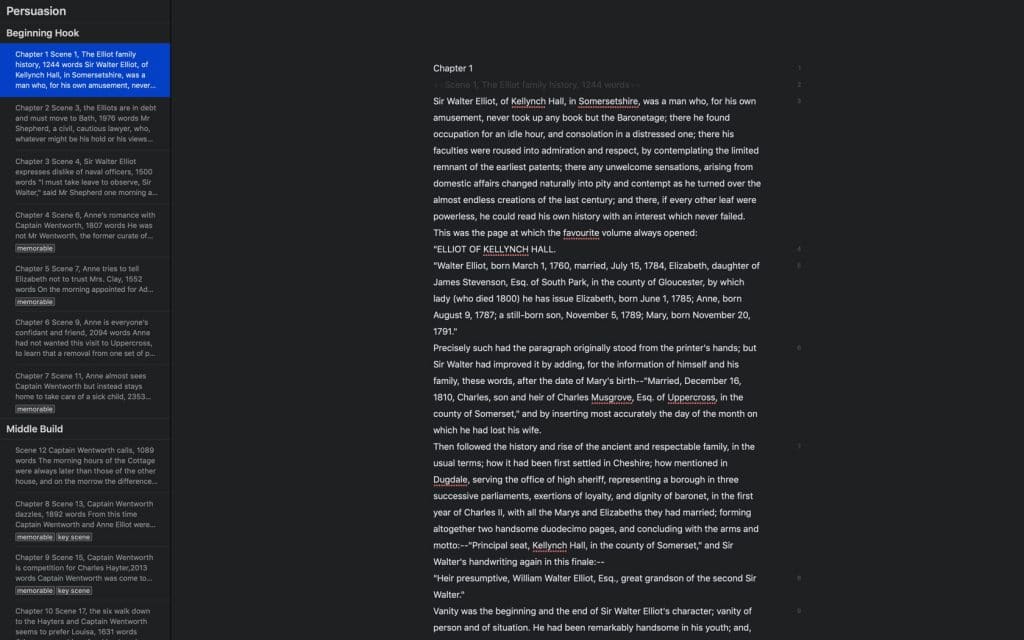

- Step two. Break the novel into scenes. If you’re fortunate enough to find a public domain novel to emulate (as I did with my example below, Jane Austen’s Persuasion), you can copy and paste the entire novel from Project Gutenberg into Scrivener, Ulysses, or another program that can break the text into sections, which makes this process a lot easier. You want to end up with a numbered list of every scene in the book.

I pasted the entire text of Persuasion into Ulysses, then separated the scenes so that each “sheet” (shown on the left) is a single scene. I then designated where the beginning hook, middle build, and ending payoff were. I also tagged scenes that were likely one of the fifteen major scenes that form the story spine.

- Step three. Write a brief “what happens in this scene” next to each number. It shouldn’t be more than a line or two per scene.

- Step four. Break up the novel into beginning hook, middle build, ending payoff. If you aren’t sure (it’s a lot easier to figure out these macro factors after doing a spreadsheet!), use Shawn’s 25-50-25 proportion and make a good guess.

- Step five. Now for the fun part. Do you know what the global value for your genre is? No? I suggest doing a search on the Story Grid site for editor Rachelle Ramirez’s excellent genre series. Once you’ve figured it out, write it out and keep it in front of you. And next to every scene on your list, ask yourself how the scene expresses that global value. Where on the trajectory does it reside? For example, in the thriller genre the global value is from life to death to damnation. In every scene, there should be a parallel value shift that mimics that range. Note it down.

- Step six. Express the value shift with +/- symbols. In other words, in a scene that goes from happy to sad, you can write +/-. In a scene that goes from happy to devastated, you can write +/- -.

- Step seven (optional, most beneficial for visual types). Graph the trajectory roughly on a white board or sheet of paper. This is the experience that the novel delivers, viscerally, to the reader, but in visual form..

What you’ve done is to create a road map (the macro) based on scenes (the micro). This is what the spreadsheet is intended to help you do.

I estimate that the above quick method of analyzing a masterwork takes me perhaps ten hours if it’s a book I know well. If it’s an older book that I can grab from Project Gutenberg, it’s not particularly difficult to map out the scenes, and if I have trouble trying to figure out the beginning hook, middle build, and ending payoff I just use Shawn’s handy percentage guidelines, bearing in mind that art doesn’t always take kindly to analysis. What’s genuinely difficult is settling on the values for each scene, but if I am determined to pin down some sort of value regardless of whether I am “right,” I can go through those fairly quickly as well.

You can use this to outline a book, create a roadmap for Nanowrimo, or to check your work. It’s a lot quicker than doing a complete spreadsheet.

Once you’ve tried the quick method, what I hope is that you will see the virtue of the full spreadsheet. Yes, it’s a lot of work! However, endlessly stewing over a story that doesn’t work is also many hours of effort. Let’s cut through all the agonizing and accept that while the individual scene analysis isn’t “fun,” hard work is usually not “fun” but is the only path to great things. Studying masterworks that we already know are good is actually a shortcut to doing the big spreadsheet on our own work. Once you’ve done it, you’ll never be satisfied with anything less. Let the end result, the masterwork, inspire you.

(All images above are from the amazing collection at New York’s Metropolitan Museum of Art, which offers more than 406,000 hi-res images of artworks in the public domain, free to download, share, or use in any way without restriction. I’ve chosen images from the “masterpiece paintings” collection; if I were learning to paint, I would study these artworks in order to figure out where to concentrate my own efforts!)