The Case for Analyzing Masterworks, Part I

How to use Story Grid and your favorite books to create a book your reader can’t put down

About a year ago, the gods smiled on me, and I became a member of the very first cohort of certified Story Grid editors. After an intense week of training under the direction of both Shawn Coyne and his partner in crime Tim Grahl, I went out to “go forth and conquer” in the name of Story Grid.

One of the first things I did was to contribute a full-blown analysis of a classic book for the Story Grid Edition series of masterworks. Black Irish Books expects to be publishing these volumes starting at some point in 2019. Shawn Coyne edited an annotated Story Grid Edition of Pride and Prejudice in 2017; future Story Grid Editions will have a similar focus: the evaluation of a masterwork using Story Grid tools. I could have chosen practically any title at all to analyze, but after a lot of thought I decided to work on Frankenstein, by Mary Shelley.

In this article, I’d like to take you through just a few of the fascinating writing insights that I discovered by embarking on a thorough Story Grid analysis of a masterwork. Next month, in part two of this masterwork series, I’ll try to convince you to do your own analyses of your favorite masterworks by sharing some of my work from Frankenstein as well as a method that I’ve developed to create an abbreviated masterwork analysis.

How does one choose a masterwork to analyze?

I am not a horror reader. I don’t watch horror movies, either. I remember walking out midway through The Silence of the Lambs back in the 1990s when my husband rented the videotape for us to watch. And I’ve never even read a Steven King novel. As you can tell, I’m not the sort of person who enjoys traversing the emotional trajectory that goes from life, to death, to a fate worse than death. My book pile usually consists of entertaining YA novels, Booker Prize winners, and historical fiction.

But I chose to analyze Frankenstein for a few key reasons. First, I’d never read it before, and as a fan of the Brontes and Jane Austen, Mary Shelley was an author I felt I should have read long ago. Here was my opportunity to make up for this hole in my education. Second, I was interested in working on something where the very publication of the book represented ideas that were fresh and original, and Frankenstein is nothing if not original! And third, I knew that by avoiding the extreme emotions stirred up by the horror genre, I have probably been missing out on something that would be valuable for me to examine and perhaps even integrate into my own work. In other words, it would be good for me.

And I was right. It really was good for me. As I mentioned, I’m not a horror writer and I don’t even read horror or watch horror movies. But by choosing a book that has endured over the centuries, inspiring stage plays, movies, and countless spin-offs in every imaginable way, I was able to see exactly how Frankenstein gets everything right. And what’s more, I could see things that were missing from my own writing, and I realized that I was pulling back at moments in my work when I should have been pushing harder. Even the non-horror writer can learn from Mary Shelley’s deft handling of the emotions of the horror genre.

In addition, what ended up being a happy accident was the fact that 2018 is the two hundredth anniversary of the original publication of the book. It has been fascinating to see in the many public celebrations that have taken place, that Frankenstein continues to touch readers everywhere, in fields ranging from feminist theory to computer science.

My annotated Frankenstein Story Grid Edition was a big project, with the manuscript ending up at about 135,000 words. It also includes a fully fleshed-out spreadsheet and Story Grid graph. It took months to complete, but I believe that it was one of the most helpful writing projects that I could have undertaken. Structured similarly to Shawn’s Story Grid Edition of Pride and Prejudice, my annotated version takes you through Mary Shelley’s novel, chapter by chapter, examining her writing from the point of view of the eternal Story Grid question, “how do I write a book that works?” Without a doubt, Frankenstein works, and the Story Grid annotated version is designed to break it down into familiar Story Grid vocabulary so that you can see exactly why it works.

But what’s particularly exciting about analyzing a masterwork such as Frankenstein are the a-ha moments that are embedded in the text, there for you to poach and use in your own writing. Here are five of the most useful discoveries that I made as I combed through Mary Shelley’s book, separating its scenes, looking for genre conventions, and measuring its emotional “punch.”

1. First of all, horror is a particularly useful genre to learn from because the range of emotion is so extreme.

Here is Shawn Coyne’s definition:

“The horror Story is a primal external genre, an allegory for the horrific world we presently or could soon inhabit. It serves as a prescriptive or cautionary tale about how best to metabolize our darkest fears and survive. The power gap between the monster and the victim is immense and thus the victim who raises the courage to confront the force with all of their inner genius to their last breath inspire us to do the same. To win is to survive.” — Shawn Coyne

Even though I don’t write in the horror genre per se, what I discovered during my analysis of Frankenstein is that I could borrow the emotional range of horror in order to deepen the emotional “pull” of the story upon the reader.

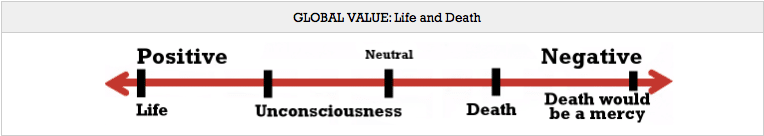

Here is the range of emotion that comes into play for the horror genre:

Story Grid editor Rachelle Ramirez recently wrote an excellent technical treatment of the horror genre, including a list of the obligatory scenes and conventions. For what it’s worth, I found everything in Frankenstein that should have been there. However, because I don’t write horror, I don’t need those obligatory scenes and conventions in my own work.

But what I realized as I read and analyzed Frankenstein was that Mary Shelley drags us repeatedly from one end of the spectrum to the other, and that an un-put-downable book does that. A horror novel should be upsetting, but likewise should a love story or a society novel. A page-turning book should cause tension. I’ve written a couple of love stories, so I paused to consider what this quality means for the love story.

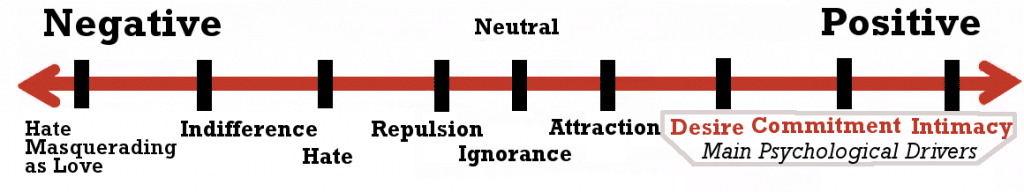

Here is the range of emotion for the love story:

Note the full possible range of emotional experiences for lovers! It is not merely love versus hate. What could be more despicable and hurtful than “hate masquerading as love?” Put that experience into a story where it can be juxtaposed against true intimacy and you’ve got an emotional range that rivals horror with its life-versus-damnation setup.

After allowing Mary Shelley to get into my head and deeply upset me, I understood much better what my fictional lovers needed to do if I wanted my readers to agonize over their fate.

2. The author ups the stakes drastically at every opportunity.

In my work as an editor, I have often found that beginning writers are reluctant to torment their characters. Even when they do put their characters through stress, they don’t want to really harm them. They give them easy outs and sudden magical powers that appear out of nowhere and without explanation, just when you think something is about to happen. Those scenes go flat, and because they are flat, you don’t actually notice anything “bad” about them individually. They technically work. The problem happens when you have many such scenes in a single book–the macro storyline doesn’t grab and hold your attention.

For a really gripping read, you will want to make your characters’ decisions and problems have real consequences.

Mary Shelley could have had Frankenstein build his monster out of animal skins and plaster. But no, he crept around graveyards and used human body parts. She could have had the monster threaten and cause random destruction. But no, he murders people whom Frankenstein loves.

There is a desperate chase through the Arctic where ships get stuck in the ice, and later, a death penalty imposed on an innocent victim. Her friends turn on her, and no avenging angel swoops down to save her.

Think carefully about stakes and consequences when you throw problems at your characters. Even if you aren’t writing action or horror, give your characters real problems to worry about, problems that can’t be solved with a loan from a friend or a phone call that clears up the misunderstanding. Think bigger and more stressful.

3. Use happy, positive events and passages as a way to strengthen and deliver the bad and the scary.

After I had gone through a portion of Frankenstein, I began to notice a pattern in Mary Shelley’s scenes. Specifically, she almost always prefaced bad situations with good situations. Here was Frankenstein’s family, filled with the love and affection of his beloved mother and foster-sister Elizabeth. Then his mother dies, after which he leaves his family and is alone at school, where he starts down the path that eventually ruins him. It’s much more dramatic than if Frankenstein’s childhood were terrible and sad. Frankenstein’s lonely monster, upon discovering the poor but kind family in its hovel, decides that he wants to join their family. The monster tells you that he plans to reveal himself, and happily daydreams about the wonderful family that he is about to gain. And like with any gothic horror movie, the reader spends several pages silently screaming, “Nooooo! Don’t open that door!” As you might expect, he is chased away because he is so ugly and frightening. Any setup that Mary Shelley creates that is kind, loving, or happy, will surely be disrupted. This pattern continues consistently as you move forward through the book.

I had been warned that applying Story Grid analysis to works of older literature could be challenging, as writers in previous centuries were working with a different type of audience, and perhaps even a different standard for prose. But I found only one or two scenes in the entire book that do not “move” or “shift” in a significant or dramatic way. If anything, because Frankenstein is a horror novel, the shifts are often predictable. You began to sense the patterns of deeper descents into horror, and to anticipate them. They often start with good feeling and the character’s belief that things are getting better…and then they don’t.

There are parts of the book where the main character spends happy months hiking in the Swiss countryside or entertaining friends. Mary Shelley’s descriptions of these blissful periods are lush and extensive. But you learn over the course of the book that these extended periods of happiness and joy exist in order to slam you into despair when bad things happen.

If you need to write a break-up scene or to otherwise put your characters through hell, try fleshing out some feel-good material first. Your bad stuff will have that much more impact.

4. Use an internal genre to complicate your external genre.

One of the most helpful pieces of advice in Story Grid is about including both an internal and external genre in the same story. Pride and Prejudice, for example, is a love story with an internal Worldview/Maturation journey. To Kill a Mockingbird is a courtroom drama, but Scout goes through her own personal Worldview/Maturation trajectory as the external plot unfolds. And The Silence of the Lambs is a thriller with a Worldview journey that ends in disillusionment.

Without an internal genre, a book can feel flat or a little cartoonish. Movies and books in the Action Genre are written that way on purpose, and those audiences probably prefer to dwell on the what-ifs of the external plot versus the internal angst of the heroine’s personal story. If you work in the Action Genre, then the following tip is optional.

As writers, we can naturally introduce internal genres when we create three-dimensional characters and give them a reason to engage with the external genre. Worldview/Maturation is a logical path for any human being to walk, and if you pay attention to the facets of the Hero’s Journey when you edit your work, you’ll probably find most of the journey right there in your draft.

Shawn Coyne discusses the juxtaposition of external versus internal genres in an article named, aptly, “Going Deep.” But Frankenstein one-ups this piece of Story Grid genius by combining two genres that are arguably the most consequential in terms of human need. Horror operates in the realm of fear and monsters, and triggers in us the”fight-or-flight” urge that human beings developed in order to survive on this planet.

Mary Shelley’s choice of an internal genre? Morality. Shelley opts for possibly the two biggest categories of struggle that human beings grapple with:

Horror: fear of monsters.

Morality: preoccupation with the nature of good.

As I read Frankenstein, I paused frequently to reflect on the utter brilliance of combining the two ultimate types of emotional trauma: temporal and spiritual.

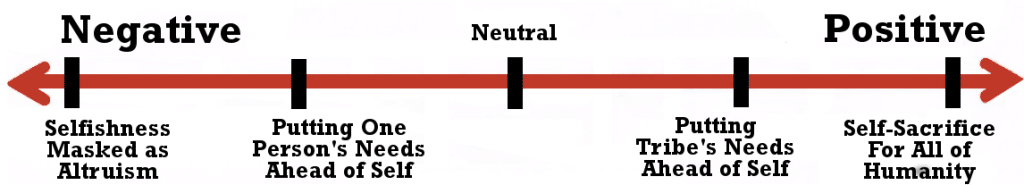

Take a look at the emotional range for the Morality Genre:

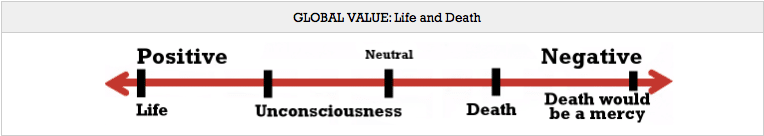

Then combine this range with the emotional range of Horror:

You can’t deny that the stakes have been ratcheted up to a level where every decision by the main characters takes on a significance that is far beyond the mere “scary story with monster.” At that point we are thinking about our role in the horror play itself. It goes beyond just a horrific setup; instead, it asks you what you plan to do about it.

Granted, we don’t all want to write stories where the consequences of our characters’ thoughts and actions have such dire results. Remember, I am not a horror reader or writer! And my last point below follows from this. How do we write satisfying, exciting stories in the genres that we love?

5. The best way for a writer to write a novel that grips the reader is to dig deep into her own past, her own emotions, her own fears and dreams, in order to address the reading experience that she aims to deliver.

Mary Shelley was a seventeen year-old girl with a married lover in 1814. She apparently expected her father to approve of this situation, as she had been taught that marriage as an institution was archaic. However, her family shunned her, as did society. After running away to Europe with her lover, she returned to England broke, pregnant, and still unmarried. Her baby was born shortly afterward, but did not survive. I’ll add that her lover’s wife was also pregnant at the time, just to complicate the story further (that detail would have been a masterful touch for a novelist, if the story weren’t true).

Let that sink in for just a moment. Imagine this kind of situation happening among your friends and acquaintances. What would you do? How would you feel about someone’s teenaged daughter running around with a married man and having his child?

She published Frankenstein four years later.

A pregnant teen today still faces social approbation and difficulty, but not to the level of what a girl in the early nineteenth century would have faced in England. While we can’t know for sure what her feelings were and how exactly all of this came together (although there are excellent diaries and letters available from the time), a book about the creation of life and the nature of good and bad choices certainly invites us to consider the possibility that the emotion Shelley expresses in it is genuine, stemming from her own experience with fear and maybe even obsessive worry over the nature of “good.”

Mary Shelley may not have been running from an actual monster, but her life story has room for a depth of emotion that she can use to tell us something about the way she sees the problems of humanity. All of us have experiences that feed into our own core emotions. We may not be pregnant teens in 1814, but we all make mistakes and we all feel afraid, both of our own standards of conduct, and of society’s expectations on us.

When I finally closed my copy of Frankenstein and thought about what it does best, I had to conclude that its gripping journey was convincing at a deep, cellular level because the author writes with a confidence that suggests that she knows what she’s talking about.

We should do the same.

When we write fear, we should jump deep into our own fear. When we write love, we should comb our own experiences for the specific feelings that we are trying to explain.

Does this mean that only a fearful, depressed writer can write about fear or depression? And that only a person with “happily ever after” romances in her personal past can write a love story that ends well? Hardly. Mary Shelley never built a monster out of body parts and never went on a murderous rampage. But when she wrote those scenes, she channeled genuine emotion into her words. She knew fear, anger at injustice and unfairness, and possibly even some level of obsessive love.

I believe that we can feel her emotion when we read her work.

Don’t pull your punches. Don’t tread lightly. Your reader wants to know who you are.

Next month: Masterworks, Part II

I know that the thought of creating a massive Story Grid for a masterwork must be intimidating, but it’s the very best thing that you can do for your own writing. Writing is inherently a long, painstaking process, and reading and studying books by people who’ve managed to figure it out is part of the process.

My heartfelt recommendation is to take the time. Enjoy the reading. Ponder the writing. Don’t tell yourself that it’s a waste of time because you aren’t churning out your own words. Studying great writing is one of the more pleasurable “jobs” of the writer.

In part II of this series I’ll talk more about the virtues of looking at masterworks, and I’ll also share a method I’ve developed that is a little less than a full Story Grid, but nonetheless can be extremely helpful for your work.