We left off last week asserting that Malcolm Gladwell relied on the power of three to reason an explanation of how Tipping Points work.

Remember the conundrum he faced?

He needed to find a simple way for readers to understand how small linear cause and effect changes lead to a dramatic moment that exponentially and explosively transitions into a big event.

Simply put, he needed to come up with a global analogy for his Big Idea. And his Big Idea is explaining how the intricately connected modern world changes. It takes our two familiar human notions of how things change…linearity and magical thinking…and makes rational sense of them.

He puts forth that it is possible that our rich experiential notions about change can be explained as components of a larger global change theory. And the critical piece of that theory is the Tipping Point.

That’s so theoretical and gobbledygooky though.

Gladwell recognized that in order for readers to “get it,” he needed one easy to remember notion that would embed in his readers’ minds in such a way that they’d be able to spread his message effortlessly and more importantly…intelligently. No one will appreciate a clichéd/cheesy/unspecific analogy at a cocktail party…Tipping Points are like lightning in a bottle.

But if the analogy makes a reader of his book relating the substance of it to friends seem brilliant, or better yet witty…then Gladwell could be confident that his reader would repeat the message (or for those of you academics out there…meme). One of Winston Churchill’s perfect analogies comes to mind…A good speech should be like a woman’s skirt: long enough to cover the subject and short enough to create interest.

What Gladwell came up with for his global Big Idea analogy is something that happens to all of us…usually at least one time a year…and something that happens all over the world…a universal human experience that everyone is able to understand without any hard intellectual cogitating.

This is what happens:

We go to work.

There’s the usual Monday at 9:30 meeting to go over progress on some company initiative. Before we sit down, we shake a few hands…ask our colleagues how their weekends were.

The project manager leading the meeting tells us to take our seats and then proceeds to drone on and on about a detail from the previous meeting that no one cares about.

We do that thing we always do to keep ourselves from nodding off. We rub the top of our forehead, shaving off a few hundred epidermal keratinocytes in the process along with a few thousand rhinoviruses that had attached to the surface of our palms when we pressed the flesh of our friends.

We then take in a deep breathe and inhale some of the dead forehead skin cells and a few hundred of the viruses. The dead skin lodges in our mucous membranes and will be ejected the next time we blow our nose and our vigilant antibody defenders zap the majority of the viruses.

But a few of those ingested viruses escape our internal defenses.

Some lodge and bind to the walls of cells that make up our pharynx, larynx and trachea. Some viruses even find their way into our lungs.

We haven’t been getting enough sleep lately and our immune system is a little slow on the uptake hunting down these rogues. The delay gives the viruses time to drill through the cell walls they’ve attached to and inject their reproducing machinery inside. That DNA reproduction goop makes its way to our invaded cells nuclei. The virus then takes over all of the resources of the cell and programs it to make virus babies.

In minutes, one virus turns into thousands inside the infected cell.

Eventually the cell, now nothing more than a virus producing machine, explodes and dies. But its death releases thousands of new viruses into our lungs and throat. Our antibodies dispatch most of these bad boys again, but because we’re run down and not taking the best care of ourselves, more manage to find purchase than the initial siege.

The linear progression of cause (virus attaches to a cell, injects itself inside and then takes over the cell and reproduces) and effect (the viruses become so plentiful inside the cell that it bursts spreading more viruses) continues throughout the work day.

But because our body has not reached a dramatic moment when the viral soup in our blood stream demands more of our cognitive attention, our brain does not tell us we’re “sick” yet.

We feel fine…even though small linear changes (viruses reproducing inside infected cells one by one) that are making us sick are happening inside our body.

We complete our day’s projects, say goodbye to our friends, head to the subway or our car for home.

We’re feeling fine at dinner too.

But when we’re giving our youngest kid a bath (nine and a half hours after that inhalation of virus at that morning’s meeting), a dramatic moment happens…

Our flu “tips” inside our body.

All of those linear one by one virus reproductions have reached a point where our antibodies can no longer fight without additional resources. Our brain needs to shut us down so that it can devote itself entirely to the internal war.

The exponential growth of the viruses inside of our body (2 become 4, 4 become 16, 16 become 256, 256 become 65,536) overwhelms us. The dramatic moment happens when our body screams to us:

“GET YOUR ASS IN BED…YOU’RE SICK!”

We ask our partner to take over the kid-washing duties and we make a beeline for our posturepedic. Our normal routine is suspended until such time as our body can create its own exponential growth of antibody warriors capable of wiping out the invading viral hoards.

Getting the flu is the perfect analogy for the trinity of progression from linear change to tipping point to exponential growth.

This epidemic analogy will hover over Gladwell’s entire book and will remain with everyone who reads it…even for the people who quit in the middle.

Gladwell never lets go of this perfect analogy. He reminds the reader as often as possible that all of the stuff he’s writing about can be understood by simply understanding the common cold or flu.

Getting a cold or the flu is an exponential experience…one minute we feel fine, the next we need to lie down. Small changes lead to a tipping point of feeling lousy and the resultant big event of having to stay in bed for 24 to 48 hours to recover.

The second our brain tells us… “You’re sick!” is The Tipping Point. Small things…like microscopic pieces of DNA attacking single cells in multibillion celled personal organism…reach a critical mass of infection, tipping our brain to tell us that we need to go to bed, to rest, to give our immune systems the energy necessary to call up more troops and take the fight to the enemy…

There’s a threefold relationship…1) linear cause and effect leads to 2) a tipping point that 3) creates exponential growth.

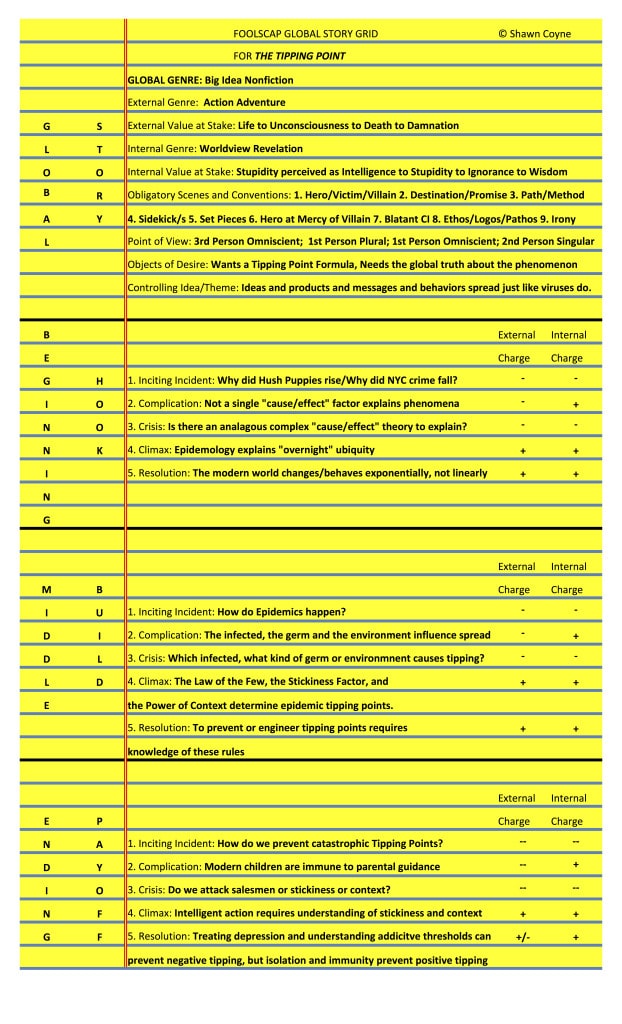

Which is a perfect transition into my completed Foolscap Global Story Grid for The Tipping Point.

Why?

Because The Foolscap Global Story Grid is one piece of paper (the MACRO of Story) that breaks down a Story into three pieces…the Beginning Hook, the Middle Build, and the Ending Payoff. There’s that number 3 again!

So here it is:

Up next is the Story Grid Spreadsheet (the MICRO of Story) for the Beginning Hook of Malcolm Gladwell’s The Tipping Point.