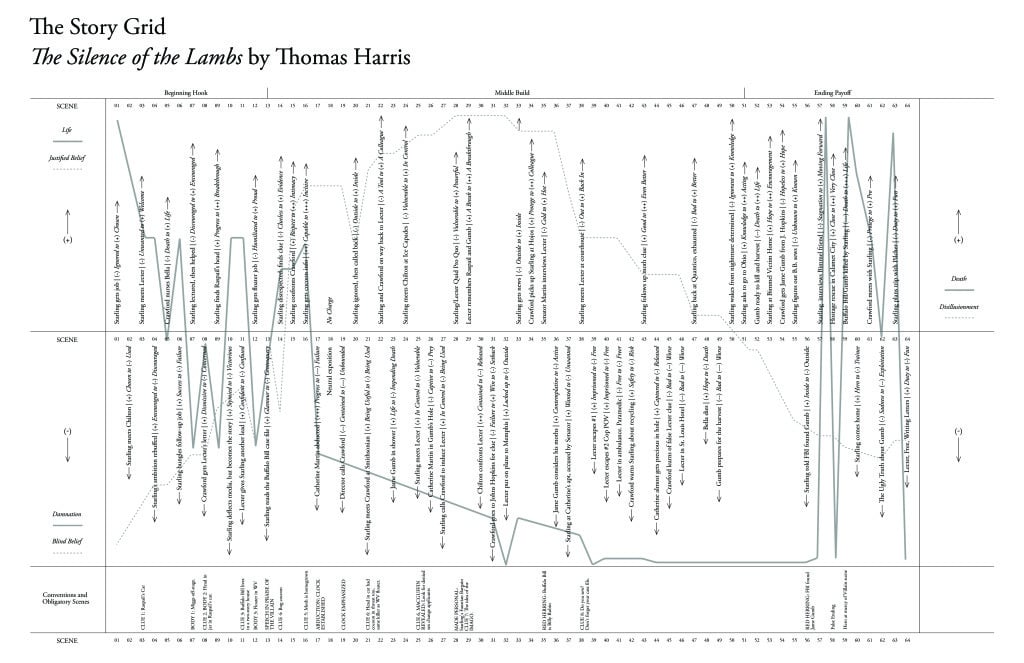

So, we’ve tracked the entire scene-to-scene movement of The Silence of the Lambs in terms of its external and internal values. And we’ve identified quite a number of places within its scenes where Thomas Harris has abided by the conventions and obligatory scenes of his chosen global Story—the serial killer thriller. We’ve also tracked the exact places where the Beginning Hook has transitioned into the Middle Build and where the Middle Build has transitioned into the Ending Payoff.

Let’s now load all of that information into a final Story Grid so that at a glance, we’ll be able to remind ourselves where Harris did what. The real value of The Story Grid is in its immediate gratification. That is, in the years prior to creating The Story Grid infographic, every time I had a question like “When did Thomas Harris drop in his clock?” I had to go look at a pile of notes.

And I’d have to dig through it until I found the answer. I don’t know about you, but once I found that answer I’d often forget the original question I was trying to answer!

But now with The Story Grid, all I have to do is look for the clock moment on the grid. Then I’ll know it was in scene 19 (chapter 17), six scenes into the Middle Build. Similarly, when you map out your own Story Grid for your work in progress, you may see that you’ve jammed a whole bunch of stuff into one series of scenes, or your values are not dynamically moving in the way that they should. Seeing it visually as opposed to trying to piece it together in your brain intellectually will be extremely useful.

So our final Story Grid for The Silence of the Lambs with all of the crucial conventions and obligatory scenes marked as well as the BH, MB, and EP demarcations follows. This is the humungous version I’ve been writing about the past couple of weeks, for serious Story Nerds only.

The Story Grid is all about getting from “Doesn’t Work” to “Works” to “Holy Moly This is Incredible!”

Remember, like a joke, if your Story has three major movements—a Beginning Hook, a Middle Build, and an Ending Payoff—for a simple, compelling premise, it works. But that doesn’t mean a publisher will offer you a contract or that one million or even one person will buy it.

Now having something work is nice.

But we all know that some jokes are good and make us chuckle and some make us spit out our food. Same with Stories. Some are okay. Some change our lives.

If you want your Story to be great, you’ve got to hone it and edit it yourself.

Even if you get a Big Five publisher to take it on…especially if you get a Big Five publisher to take it on. The publisher has bought your Story because they are confident that it will sell to a critical mass of readers “as is.” That’s their job. Whatever editorial commentary they provide after they’ve bought it will be first and foremost all about getting their investment back! So they’re not going to ask you to take another look at your Lovers Kiss scene and make it less cheesy. A lot of people like cheesy…probably more than those who don’t. Only you will care enough to really push yourself to take it from cheesy to heart wrenching.

Now, you may wish to have a greater impact in the world than just selling to ten thousand people (hitting that number is a huge success regardless). If that is the case, you need to know how to analyze and improve the work you’ve already done without killing the good stuff. This is what The Story Grid is for. It’s for fixing flaws and bettering strengths.

If you write a better Lovers Kiss scene than the solid cheesy one you’ve written before, readers will recognize it. They want that better scene. They really do. And if you give it to them, they’ll come back for more of your work in the future.

If you use The Story Grid tool rigorously and do not give in to the “good enoughs,” it will definitely prove the difference between “nice work here, but it’s not quite right for us” to “we’re getting our numbers together to make you an offer.”

It’s my contention that most writers don’t fear the work. They want to do the work. No one, though, has clearly laid out in practical terms exactly what that work is. I built The Story Grid methodology to do that.

Most amateur writers understand the general concepts of Story: that they need a compelling Inciting Incident and that they have to satisfy the expectations of their audience for the particular Genre they’ve chosen to write. But they have no idea where to begin and no idea of how to analyze their work after they’ve done some of it to make sure it can withstand the critical winds and turbulent external forces of nature. The problem that bedevils most novice writers (and even some seasoned pros) is that they fall in love with the glamorous aspects of the literary trade—the romance of “the creative process,” the thrill of dashing off chapter after chapter in a white heat of inspiration, etc.—and they undervalue the blue-collar aspects of Story construction and inspection—understanding and mastering Genre, Story form, character, Story cast, and so forth.

They fail to learn how to edit.

The inescapable fact is that you need an editor who cares about making your book not just “work” but for it to transcend its Genre…to break new ground in such a way that it changes the way people see the world. And there is only one editor alive with that kind of commitment.

You.

For new subscribers and OCD Story nerds like myself, all of The Story Grid posts are now in order on the right hand side column of the home page beneath the subscription shout-out.