Every story has an All is Lost moment. Without it, the protagonist cannot undergo true change.

You as a writer should encounter that moment too, in every story you write. When you rise to the challenge, it will make you a better writer.

But we’ll get to that later. First, let’s define the beast.

What is the All is Lost Moment?

The All is Lost moment is a critical midpoint, a turning point in the Global Story. It is the point of the story when the Global Crisis is distilled into a single question that cannot be answered without a loss, whether it’s a best bad choice or irreconcilable goods.

The All is Lost moment is the crucial element of the Middle Build. It’s the pivot point when the protagonist shifts their pursuit of what they want to the realization of what they need. And that can stop them dead in their tracks.

Think of it as the fulcrum of your story.

It happens in the movie Crazy Rich Asians when Rachel is confronted by her boyfriend’s family at a wedding reception. They’ve had her investigated and reveal information about her mother’s past that’s been kept secret from her. Nick’s mother and grandmother tell her outright that she’ll never be accepted as Nick’s future wife. Rachel lashes out reactively, telling them that she doesn’t want to be part of their family, and flees.

Up until this moment, Rachel has wanted only to make a good impression on Nick’s family. She knows his mother doesn’t like her, but she feels she’s formed a bond with his grandmother. All that is swept away in an instant, PLUS they’ve dropped a bombshell on her that undermines everything she thought she knew about her own roots.

Rachel’s pursuit of her object of desire, wanting to be accepted by the Young family, is utterly destroyed. She is as far from that original object of desire as she will ever be. Even her rock-solid relationship with her mother has been shaken to the core. It’s a powerful turning point for her.

Alternate Designations

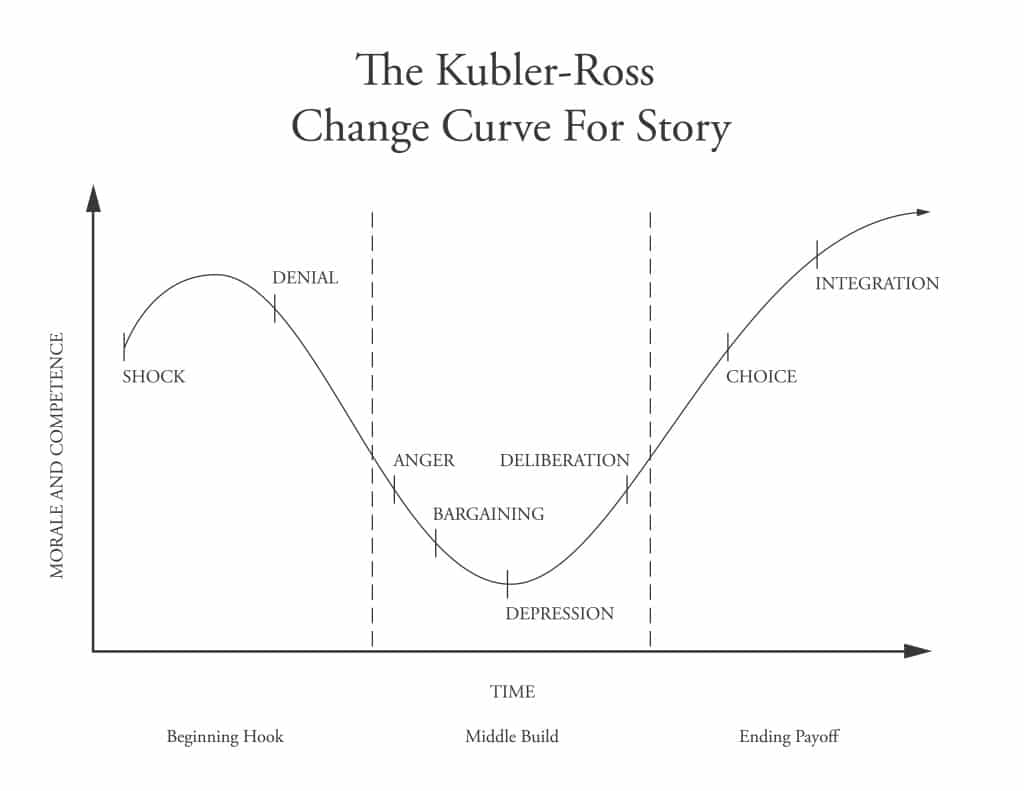

It’s easy to locate the All is Lost moment along the Kubler-Ross arc. It corresponds to the fourth stage: Depression and it’s the absolute bottom of the arc. Rachel exemplifies this by retreating to her bed and refusing to deal with life. While it’s not evident yet, it is the very beginning of her path to understanding what she actually needs to resolve the story’s conflict on her own terms.

The All is Lost moment is also the low point on the Hero’s Journey. It corresponds to the Ordeal, Death and Rebirth, the Eighth Stage in Christopher Vogler’s version. It signifies the death of the old self. For Rachel, the fiction of her own family’s origin story is stripped away. The Old Rachel is irrevocably gone

Shawn describes it as “a moment at the end of your cognition,” in other words, cognitive dissonance.

Where to Put the All is Lost Moment

The All is Lost moment occupies a significant place in the Story Grid Global framework. A significant turning point of the Middle Build, It can occur anywhere from the midpoint to the end of the second act. It precipitates the Global Crisis and sets up the overall story Climax, and it almost always takes place in one of the fifteen core scenes.

A flagging Middle Build is a symptom of a weak All is Lost moment. If you’re having trouble writing with your second act, go back to your All is Lost moment. Functionally, it serves to tie the story in both directions. It forces the character to look back and see how the shock of the Inciting Incident has irrevocably changed their life, AND it plays an instrumental role in propelling the action forward toward the Ending Payoff of the Global Story.

The Mechanics of the Moment

Remember the fulcrum I mentioned? Here’s what happens when we reach that tipping point and the shift in balance occurs.

The mechanics of the moment are pretty self-evident.

For starters, the main character stops trying to regain the world they lost, the ordinary world before things were disrupted by the inciting incident. The old definition of normal has taken a vital hit. Most importantly, they can no longer avoid the painful evidence that their worldview is somehow wrong. Something has happened to them that causes them to see the illusion, self-delusion, and false information. They realize that the stories they’ve been feeding themselves and believing in are bullshit.

They can’t go back to the way things were or escape unchanged. Whether they rise to the challenge, avoid confrontation, or even if they flee, their life will never be the same.

Objects of Desire: Wants and Needs

The protagonist’s original object of desire is their want, the thing they are consciously striving for. They take an action and, based on their previous experience, expect a particular outcome. Stories need conflict, so there is a difference between the expected outcome and the actual outcome (McKee calls this the Gap.) Faced with an unexpected reality (what Shawn calls a phere), the protagonist tries a different tactic. This results in another gap, and this cycle happens again and again with unexpected outcomes and escalating risks related to the value at stake (progressive complications) until the protagonist has run out of options. Their life experience no longer offers them options to overcome the adversarial force. The well runs dry and they stare into the jaws of defeat. The moment has come. All is lost.

The All is Lost moment can play out in different ways. It’s the moment when the character can see no possible chance of ever getting what they want. Or they realize that what they want is absolutely no good to them or for them. Shawn says they “realize the want itself is wanting.”

Either way, the forward motion toward the object of desire is halted and they don’t yet understand what they need, what the true solution to their problem really is.

The loss of their original object of desire strips away the motivation that drove them to this point. It puts the protagonist completely out of their element; they don’t know what’s going on and they’re incapable of acting normally (or at least what’s normal for them, up until now).

Then something beautiful happens. Want is abandoned and need is discovered. The protagonist may still look and feel defeated but now they pursue something new. Even if they are beaten, they will at least go down with dignity. This is beautifully played out in the movie Rocky. Rocky knows he can never beat Apollo. There’s nothing he can do to change that. He’s going to get his ass kicked. All is definitely lost.

But he digs deep, and finds pride enough to determine that he’ll go fifteen rounds with the champ. He’ll take that ass-whipping and turn it into a personal victory. He’ll walk out of the ring having proven to himself he’s not a loser. Rocky has experienced apotheosis, the direct outcome of the all is lost moment

The All is Lost moment pushes the protagonist to the point of no return. Only now can they begin to climb out of their hole and begin the final journey toward the global climax.

A writer must clearly identify the moment in the story when the protagonist makes the shift from Want to Need. That’s what makes us root for a character. We want them to figure it out. We want them to win, even if they lose.

The All is Lost Moment and its Relationship to the Controlling Idea

When the stakes are not Life and Death, as is the case in the internal genres, the low point comes when the character realizes they’ve denied some part of themselves to their detriment. They may realize they actually hate themselves or, if they continue on the same path, they’ll reach some sort of damnation. They’re staring the negation of the negation right in the face.

Now that they realize things are not going to turn out the way they thought they would they’re faced with the choice to change or fail. The choice they make lies at the heart of a story’s theme, whether it’s the positive or negative expression of the genre value at stake.

There’s a lot packed into that connection, so let’s break it down.

We know as Story Grid writers that the first choice we commit to is genre. Genre tells us what values are at stake in the story. Once we know the value at stake, we can uncover the story’s theme, or controlling idea. And theme can be expressed as a positive or a negative.

Let’s take the Worldview genre and drill down to the Education subgenre.

The global value for Worldview-Education is meaningless and meaning. The forces opposing change ultimately reside within the protagonist, as for any of the internal genres.

The positive expression of the controlling idea of a Worldview Education story is “Wisdom and meaning prevail when we learn to express our gifts in an imperfect world.”

Its negative expression goes like this: “Meaninglessness reigns when we fail to mature past a black-and-white view of the world.”

For the positive expression of the theme, let’s look at How the Grinch Stole Christmas. When the sleigh full of toys is teetering on the edge of the cliff and the Grinch hears the Whos singing he suddenly realizes that everything he thought about Christmas up until now is wrong. This is his All is Lost moment. He is, of course, deeply moved, and chooses to change for the better.

The theme is negatively expressed in the movie Up in the Air. The protagonist’s All is Lost moment comes after anchorless frequent flyer Ryan Bingham experiences an epiphany and abruptly leaves his sister’s wedding to lay his heart at the feet of a woman with whom he has an ongoing relationship of convenience. He arrives on her doorstep only to find that he’s no more than a convenient hookup for her. Unable to form an emotional connection, Ryan returns to his relentless pursuit of frequent flyer miles, remaining anchorless and unattached.

For the Grinch and for Ryan, the choices they make in response to their All is Lost moments express the core theme of each story.

Everything Changes

The All is Lost moment is when everything changes for the protagonist. No more magical thinking. They finally stop bargaining with life and face the truth. The protagonist shifts from reactive to proactive.

That’s an important distinction. Your main character stops merely reacting to the conflicts thrown their way by the antagonist, and starts bringing the game to them.

You’ve probably heard someone say that the Middle Build belongs to the antagonist.

It’s during the middle that the antagonistic forces exhibit their greatest power, thrusting the protagonist into despair. But the All is Lost moment is where it begins to change.

Multiple All Is Lost Moments

In a love story, the All is Lost moment isn’t necessarily when the characters break up or separate. It can happen in other ways, like when they realize how meaningless their life is without that other person. They want them back and have no idea how to make that happen. In fact, Shawn advises against the breakup as the All is Lost moment to avoid melodrama. He suggests that it turns instead on the secondary plot, the driving force that impacts the lovers’ relationship. (In Crazy Rich Asians, it’s Rachel meeting the family. Love stories always work better when twinned with another plot.)

In Pride and Prejudice, it comes for Darcy when he first proposes and Elizabeth rips him a new one. That certainly wasn’t what he expected. His worldview has been shattered. Darcy begins to realize that everything he believes about the world is wrong. He begins the road to change. For Elizabeth, the moment comes when she realizes the role that Darcy has played in mitigating her sister’s scandalous marriage.

Love stories have an All is Lost moment for each protagonist, and the two do NOT have to happen at the same time. In fact, you can use these different moments to ratchet up the tension and inspire innovative obligatory scenes and conventions

All major characters can (and probably should) experience some sort of All is Lost moment.

Shawn advises that taking each character in an epic story to the end of the line gives you a multi-layered, multi-stranded story. This is especially effective when each supporting character represents one of the protagonist’s characteristics. Robert McKee recommends this strategy in creating a memorable character ensemble.

And yes, even an antagonist can experience an All is Lost moment.

We’ve seen that the protagonist learns from their mistakes, undergoes change, and succeeds. Conversely, the antagonist does not. That capacity to change is one of the fundamental differences between a protagonist and an antagonist.

Apotheosis

If the All is Lost moment is one side of a coin, the flip side is the apotheosis.

Apotheosis is defined as “the highest point in the development of something.” The word comes from the Greek words apo – from and theos – god. In combination, they form a word that means to make a god of (something or someone).

The apotheosis comes when the protagonist reaches the highest point of their development or journey. All their trials and troubles and obstacles have taught them to reach inside themselves and uncover their unique gift. In the Hero’s Journey, we say they’ve Seized the Sword or Received the Reward. They are given a gift or dredged it up from where it’s lain hidden inside them.

That can’t happen until they’ve hit their darkest moment, a point they feel that all is truly lost.

In the Middle Build, the character hits a point where their decisions become irreversible. Remember, character is all about the choices they make under pressure. Actions speak louder than words. Here’s where the writer shows the true nature of the protagonist.

Everything they’ve done up until now hasn’t been enough. They must shed self-delusion and accept the truth about themselves, the situation, the way the world works. In order to defeat their enemy or adversarial forces, they must change in a way that they’d never considered before. The All is Lost moment is the catalyst of this change.

A character’s response to the All is Lost moment – the choice that they make in response to the global crisis – doesn’t have to fully manifest right away. Despite the direness of the situation, they are actually on the brink of transformation. Their choice will come to flower fully in the climax.

Following the despair of the All is Lost moment comes the transformative Apotheosis, and this killer combo is what kicks off the final push to the story’s ending payoff. Now the protagonist must use their gift on the Road Back. Simply understanding or discovering the gift isn’t enough. They must put it to work.

The expression of the gift that arises from the All is Lost moment is what drives the Climax of the story.

The Writer’s Transformation

The All is Lost moment isn’t just a device to test the mettle of your characters. It happens to you during the writing process as well.

Tim related at Story Grid Live 2019 a version of his own All is Lost moment as a writer, and how changing his approach helped him solve a story problem. He had written himself into a hole and put his character in a situation he had no idea how to get them out of. He was stuck. He’d written several versions and still couldn’t make it work, until a piece of new information from another part of his life changed the way he thought. It flicked a switch for him and he was able to achieve his need of a scene that was not only an innovation interpretation of a genre convention but a succinct expression of his theme. It gave his story heart and revealed his controlling idea.

Writing the Middle Build is hard. It’s the longest act and it happens between the promise of the Beginning Hook and the excitement of the Ending Payoff. You wouldn’t be the first writer to get lost in the swampy middle. By the midpoint of the story, the All is Lost moment is looming, and the lowest point of hope at hand.

It can be the low point for the writer as well. You get to that point in the story and you don’t know how you’re going to figure it out, how to give the reader an inevitable but unexpected ending.

Anyone who has done anything difficult and challenging in life – something like writing a book – has faced an All is Lost moment. It’s a special opportunity to connect with your reader on a very human scale.

In Tim’s Running Down a Dream, he hits it when he’s broke and he’s going to lose his house. He faces up to the hard truth that he can’t keep doing what he’s doing. He has to change himself by changing his worldview. And if you’ve read that book, you know it’s not a Cinderella story. Fall down seven times, get up eight.

Shawn says do everything you can to dig yourself that insurmountable hole, because you will write something amazing to solve it. Write that moment so that it seems there is no way out for the character. Push yourself and your story to a point that you can’t figure it out in five hours, or even five days. You’ve got to dig deep and find your true gift. It’s there. Challenge yourself as a writer and take risks to put yourself in that unsolvable dilemma. Trust that you’ll find a solution.

Make your reader wonder how your protagonist can possibly pull this one off by writing yourself into that corner. It’s what keeps your readers reading to find out how you’ve solved the impossible.

A writer must be willing to confront the darkness, on the page and in themselves.

Push yourself and your character to the moment of transformation. Do this, and your characters will exceed their own capacity. And so, as a writer, will you.

Special thanks to SG editor Leslie Watts for helping clarify and emphasize the ideas in this article.