Malcolm Gladwell, back in 1998, faced the same writing dilemma we do today–having “easy” access to the nuts and bolts of book publishing, but struggling with whether we’re good enough to make use of the opportunity.

As he sat down to the pile of rough “Tipping Point” book materials on his desk that would be fodder for his first draft, he feared criticism, failure, indifference…all that stuff.

While the intangible things he had no control over must have terrified him, I’m confident that the one thing he didn’t fear was the work. Perhaps the difference between Gladwell and us, in just about all cases, is that he’d worked his ass off for twelve years hitting story deadlines time and time again as a magazine and newspaper journalist to hone his craft.

But it was the constraints—those rare positive seven figure ones, the most difficult to overcome—Gladwell had to toil under that could have driven him crazy. He didn’t just have to deliver a manuscript that would be edited and copyedited and proofread and dumped into a publisher’s catalog on page 37 next to another writer’s midlist business book. He had to deliver a 1.5 million dollar book…a BIG BOOK that would be a two-page spread, front of the catalog big deal, with every one of his publisher’s marketing bells and whistles attached to guarantee its bestsellerdom.

How did he find himself in this predicament?

How did he reach a place in his writing life when a powerful literary agent picked him as her next development project? From the rich stew of journalists that publish their work every month, or week or even every day in all of the “A-list” periodicals across the country and even around the world?

Gladwell doesn’t have a post-graduate journalism degree from Columbia. He isn’t an Ivy Leaguer B.A. either. And he’d only just begun writing for The New Yorker when he got his “big break.”

So what gives?

I think three things were instrumental in his inevitable path to The Tipping Point:

- His mother and father

- His inner Paavo Nurmi

- His exposure to the realities of the often intimidating idiosyncrasy of academia

Born in England and raised in Canada, he is the son of a Graham Gladwell, a white math professor from Kent, England and Joyce Nation, a Jamaican born and bred therapist and writer. The Gladwell parental units met as students at University College, London, fell in love and got on with building their life together…stoically…all in the era of miscegenation hysteria.

Gladwell has written evocatively about being both white and black and thus neither black nor white. And of his general otherness growing up in Elmira, a Mennonite community in Waterloo, Ontario where his father taught at the University.

But when questions of “What are you?” arise as they did in his youth, Gladwell prefers to push them to the periphery.

As one might expect from his cerebral work, Gladwell kept to himself as a kid. He preferred to hang out at his father’s office at the University of Waterloo exploring its halls and libraries and carrels than putting in the hours at the local rink like his contemporaries.

While the first to admit that he hasn’t a clue of what his father’s work was all about, seeing the human beings behind the papers that filled the journals that lined the library shelves made him comfortable with PhDs and PhDs in training. The guy who spoke of Taylor and Maclaurin series’ like people today speak of the Kardashians and Jenners was his just his goofy dad, the same man who liked to go to Menonnite barn raisings or organize a group of kids in a game for entertainment. Having inside access to the humanity behind the scholarship demystified the ivory tower for Gladwell. It even made him fond of them.

Gladwell describes not playing hockey in his hometown as the equivalent of living in Munich and not drinking beer. Instead of mastering the slapshot, he ran. Not just for fun, but competitively.

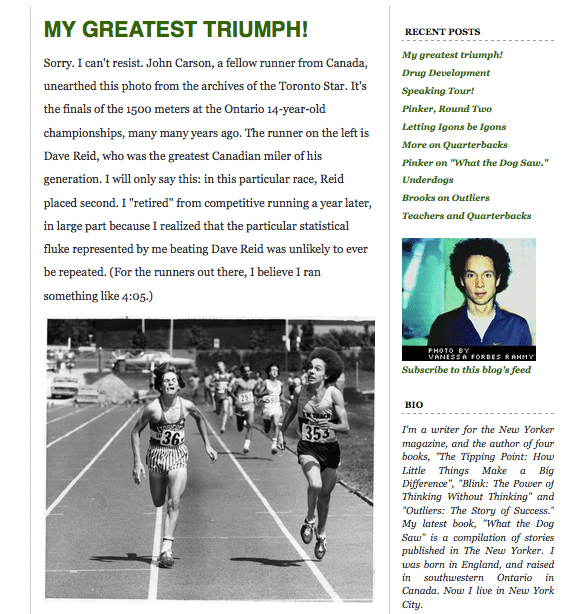

His dedication and determination rewarded him with a victory in the 1500 meters (just about a mile) in the 1978 Ontario High School Championships. His time was 4 minutes 5 seconds…enough to beat the future Canadian record holder, David Reid.

Imagine doing anything to the point where your heart cannot pump oxygenated blood fast enough to supply your body’s demand? For anyone who has ever had to run as fast as they could for a length not conducive for sprinting, Gladwell’s performance is stunning.

Running the middle distance requires the long view of a marathoner to set and maintain a pace, but also the nerve of Usain Bolt, a willingness to burn through all reserves in a final rush to the finish.

Running the 1500 meters will also answer a simple personal question.

How much stress and pain can you endure and still perform?

Gladwell found out of what stuff he was made at fourteen.

That’s a formational life victory. Before he wrote one word as a professional journalist, Gladwell knew how to press himself across a finish line.

After a desultory experience in college—he graduated with a History degree from Trinity College at the University of Ontario—Gladwell pursued an advertising career.

Every agency rejected him. He had none of the flash of an adman. Not even the potential of sizzle.

But with a 1982 summer internship from the National Journalism Center on his resume, he found a position as an assistant managing editor at the conservative magazine, American Spectator. A stint at Insight magazine and freelance work at The New Republic followed. In 1987, the The Washington Post beckoned and he’d made it to journalism’s big show.

As a sometime utility infielder though, not a front-page feature writing superstar.

Gladwell spent nine years and his oft-quoted ten thousand hours honing his craft covering business and science for the Post, rising to bureau chief of the New York office.

Then in 1996, the sizzle queen herself Tina Brown hired him as staff writer for The New Yorker, the equivalent of getting journalism tenure. He’s been there ever since.

The first piece Gladwell wrote for the magazine was called Blowup, which was categorized under The New Yorker rubric, “Department of Disputation.” A revelation story about accidents, it riffs on a theme that will become Gladwell’s bread and butter—what we accept as common sense wisdom is spectacularly inaccurate.

At the heart of Blowup, which explores the myriad of little “acceptable risks” inherent in big technological efforts like the risk of an O-ring failure during the launch of the space shuttle Discovery, is this sentence…

What caused the accident was the way minor events unexpectedly interacted to create a major problem.

In other words small things can have big effects.

His next extended piece, Black Like Them appears in the April 29, 1996 issue under “Personal History.” It tells the success story of his Jamaican cousin Rosie and her husband Noel over everyday racism. As they make their way in a New York suburb, the struggles American born blacks face in the very same neighborhood juxtaposes their travails. It ends with Gladwell recounting a meeting with a friend who did not know that his mother was Jamaican. His friend blames all that ails Toronto on the influx of West Indians into Canada…and it ends with these telling closing sentences:

In other words racism is not incredibly complicated. It is contextual. The same striving Jamaicans in New York upended and moved to Toronto would be viewed…overnight…as irredeemable gangsters.

The subtext of Black Like Them is that Racism is simply small-minded people spreading ignorant fallacies to explain away complex phenomena. It’s easier to blame someone else than to change the way you think and see the world.

Which begs additional questions: Is Groupthink of this sort as arbitrary and accidental as it seems to be intellectually lazy? Or are there ways to combat it?

At what point do small things like an ignorant friend damning an entire group of people without knowing a single one of its members critically compound to cause huge effects…one far larger than the sum of its parts?

That is, when exactly does the wear and tear on an O-ring move from an acceptable risk to an explosive failure? Or specifically, how many miserable people spouting nonsense does it take to penetrate and deposit their prejudice into the minds of others?

Gladwell’s next piece for The New Yorker will begin to explore these questions and set the stage for his 1.5 million dollar predicament.