👉 Write a book you're proud to publish 👈

Studying something that you are passionate about, even in an age of digital maximalism, can be difficult. If you’re not being pointed in the right direction by a professor or mentor, you are at the mercy of books on the craft. Of which there is an abundance. As a result, the learning process can become overwhelming. Many of these books assume that you already have a draft in hand. Of little use is such instruction if this is not the case.

One hugely important thing that I have learned from Shawn is the phrase “paralysis by analysis”, which is a term from Behavioral Science that involves overthinking or overanalyzing.

The danger of paralysis applies only in overanalyzing a story before the draft is complete. The danger is second guessing yourself into resistance. I get it—and I wish that I could pants my way to a draft, but the reality is that I rest heavily on the planner side.

It’s a daunting question to answer, pantser or planner. Which tribe do you assign yourself to? And do you have to choose one?

To be sure, both have their benefits and pitfalls. I’m not convinced that either way is superior; they are ways, and not destinations, after all. It seems to me that neither method makes you a more skillful writer, and isn’t the desired outcome to be as skillful as you dare?

Definitely yes. But the traits to be either a pantser or a planner are inherent in us, they develop with us, are part of our personalities. The question is: does having a penchant towards one method preclude the opposing skill be learned and employed to compliment our natures?

Definitely no. I’ve found that trying to be both pantser and planner—that is to say, a hybrid—has given me confidence and has boosted my productivity. Maybe you want to become a Story Grid Hybrid too.

NOTE

If you’ve already devised a writing system that works seamlessly and you’re able to churn out book after satisfying book, then I don’t propose you make any changes. But if this is not the case, let’s go over a few steps of a basic creative process and its engines to see what would allow any writer to be an efficient hybrid.

But first—definitions.

PANTSERS

The Writing

Pantsers are famous for writing their stories without overthinking structure. They might know the basics about where the story might go but in essence, they sit down and write. Beautiful and simple. I sincerely admire people that can maintain this process for an entire novel.

Details

You might forget details as you go along. Your MC’s name might change from Megan to Marcie, but you can always regularise in subsequent drafts.

Writer’s Block

I have been told that writer’s block is not so easy to overcome for pantsers because it usually means you have a knot that needs to be unraveled, and such knots are not always easy to find and release since certain details are unmemorised.

Why this method is great

Pantsing is great because you can create a rich and genuine narrative that might feel less rigid than a planned one, and the story has a potential to change and surprise you, thereby surprising readers.

PLANNERS

The Writing

Planners, as the name implies, have their story planned out before they start the major part of the writing and all they need to do is follow the map that they have made themselves and write what they intended to write. There may be small surprises along the way but they’ve have done a great job of tying up all the loose ends and going over different outcomes to situations.

Writer’s Block

For planners, writer’s block is fairly easy to overcome as they have a plan of exactly what happens in each scene. If they are blocked on a specific scene, they simply move to the next, and return to the problematic scene on a day that they’re better equipped, and when they do so, they make sure that the scene is necessary.

Details

Since they are immersed in their story well before they write the better part of it, planners are likely to remember names and ages, locations, histories, and other details about the story. They might have maps and pictures on their desks to better envision the minutiae.

Why this method is great

Planning is wonderful because you can easily catch mistakes in plot and arc, and craft a beautiful, tightly wound novel that minds and reinforces the themes every step of the way.

WHAT IT MEANS, AND WHAT CAN WE DO?

To boil it down to the roots, the main difference between pantsing and planning is that a planner plans their story and then writes it, and panster writes their story, and then plans it.

If I had to guess, both methods take the same amount of time to get through a project, with the same level of difficulty at opposite ends of the act of creation. What if the difficulty could be avoided?

What if using the 5C’s and/or the Foolscap Spreadsheet can help guide a pantser through a draft without the feeling of being bogged down with excessive planning? All of the taste and none of the calories.

And what if a planner can take a step back from the scene-by-scene to look at the 5C’s and/or Foolscap too, and be able to write freely while feeling secure that their novel is on the right track? What habits do we have versus the habits we want to have?

IDEAS AND HABITS

I am an advocate for journaling and I have journals going back too long to discuss without embarrassing myself. I use my journals to track many things, such as personal development and skill acquisition, but I also track mundane things that happen or stray thoughts. Science has proven to us that our memories decay for various reasons and having a habit of taking notes is—for me—a necessary part of my day. Somehow I feel that I can mine my own life for my stories somewhere down the road.

Since habits must be made, and are so easily undone, consider your current habits and use that knowledge to your advantage. If you can work with yourself, you won’t be working against yourself. Remember, the key here is to maintain a writing habit. The last thing you want to do is sabotage yourself into failure.

Are you a night owl? Early bird? Afternoon swan? Reserve the right time and stick to it. I know it’s easier said than done, but there it is, unfortunately there is no way around it, and I am sure you have heard many writers repeat this mantra: You have to do the work. Giving time to the process is a requisite to turning pro.

But what is the point of setting aside time if you spend half that time looking for files? Being organised is another way so speed up the process. If you have a place for each of your projects, your material will not get lost, and you will not be distracted by a thousand other great ideas you’ve undoubtedly had.

Another great habit to have is tracking your daily word count/pages/hours. If you can create a catalog of data for yourself, you can optimise your system. It could mean shifting your writing times by half an hour because the garbage truck goes right by your window at ten minutes to ten, or writing in a specific place has proven to be a more conducive writing atmosphere. Simple things can move us in important ways. That sounds like a song lyric, but it’s true.

THE SPARK

The first event in a creative process is, of course, the spark for a piece. As a compulsive note-taker, I write down details about the idea and I don’t initially organise those ideas, but let them coagulate.

What was the inspiration? What film, show, or book it is reminiscent of? Did the idea pop up because of a song heard while driving or waiting in a queue? It all goes into the notebook, pantser-style. Stream-of-consciousness style.

These sparks seem to come from many sources, there are many wells; from dreams, movies, newspaper articles, from stories we wish were different, from snippets of something we heard someone say, from truths learned the hard way. But mainly I think they come from asking what if, and being perpetually curious about everything and anything.

If these sources elude you for being too transcendental, esoteric, or philosophical, try using prompts or story generators to help get you started.

SCENESTORMING

After the spark, there are chances that you might randomly envision a few scenes. Your spark might even be one of them. This happens naturally. Our story-infused brains are very eager to present easy solutions to us, and what’s easy and obvious might not be the most original. These first scenes are not necessarily going to wind up in the final draft, but they can absolutely inform it.

The goal of scenestorming is to write down all the scenes you can envision at this point in time, and they don’t have to be perfect. You can use grids, keywords, lists, mind maps, diagrams, arrows, cue cards, post-its, butcher paper, whatever works best just as long as the ideas get onto the page. Definitely be a pantser for this part.

When you start to gain momentum and have a handful of scenes, judge if the story is strong enough to stand up on it’s own. If I find myself with more than a dozen scenes and I still feel excited, that is usually enough for me to proceed. This is a good time to give the piece its own file and assemble all the notes that seem relevant to the project, and get ready to dig for more story gold.

KNOW YOUR PROJECT

Genre is the most important thing to follow with Story Grid methodology. I usually like to go over parts 2 and 5 here. Does your story already know what format it wants to be? How many scenes do you have and how many more do you estimate there will be? Do the maths for your chosen length and re-read The Story Grid Part 3. 36. The Math.

Flash fiction ~500 words, 1-2 scenes

Short stories under 7,500 words, ~12 scenes

Novelettes 7,500 to 17,499 words, ~20 scenes

Novellas 17,500 to 39,999 words, ~27 scenes

Novels over 40,000 words, ~60 scenes

If you know approximately how long it takes you to write something, you can ask yourself some pointed questions, like what will this project take to complete, and can I embark on it right now? Am I equipped with time/skills/desire to see it finished?

KNOW YOURSELF

Do you have any quirks in your writing process? I have. Among them is the bad habit of not writing complete thoughts when I am without my gear. One forgotten notebook and it’s point form on napkins for me. I also feel that because I’ve written a scene that I can’t write it again. It’s quite silly.

I might not have that specific notebook with me, but it doesn’t mean that I shouldn’t work on the project if inspiration strikes. Besides, I might like the new version better, or having written it might spark another idea, or trigger another something that ties into the loop or story—even another scene altogether. Our creative minds seems to multiply that way.

The moral of the story? Write, even if you have to get over the hurdles of our own quirks to do it. Re-read The Story Grid Part 1. 8. Your Own Worst Enemy.

BRAINSTORMING

No matter if you’re digital or analog, brainstorming on a specific element can be liberating and enlightening. It’s the equivalent of a painter doing a few drawings of the subject before starting on the blank canvas.

Elements that might emerge while brainstorming might be about characters, details about the world you set your story in, possible locations, or the time period you want to set your novel in.

Brainstorming can help you focus on a specific subject so that when it’s time to do your research, you can hone in on the necessary information easily and quickly.

GENRE, THEME, AND VALUE ON THE FOOLSCAP

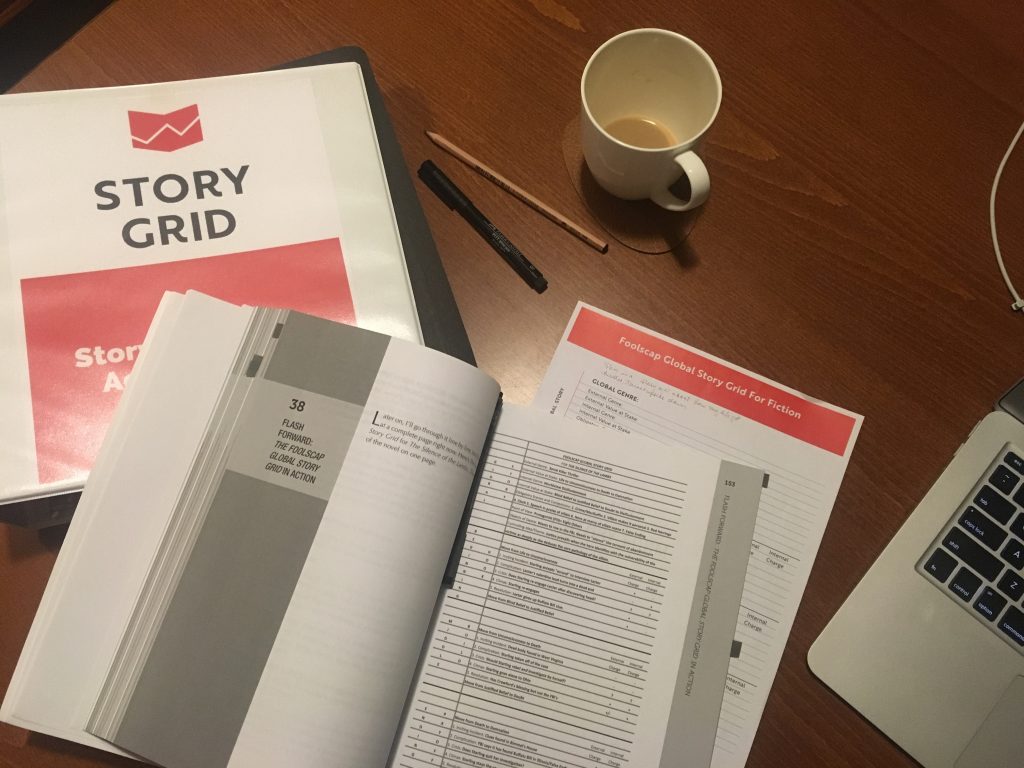

What is your story genre, what theme, what takeaway makes it valuable? When these questions come to mind, I print or write out a blank Foolscap template. Planners will be familiar with this one, and pantsers: don’t panic.

At these beginning stages you don’t have to fill it in completely. You may only complete it after your draft is finished. Having a Foolscap at hand plants the seeds in your brain that these are things that you need to pay attention to and though simple, this paper can help immeasurably—even blank.

At this point, I like to re-read parts 2, 3 and 7 of The Story Grid on Genre and the Foolscap Spreadsheet, and any podcast episodes I think will be relevant.

LAYING OUT A BEGINNING, MIDDLE, AND END

Brainstorm a few sentences for each of the main story movements, Beginning Hook, Middle Build, Ending Payoff. Because it’s a draft, I might give myself a couple of options. If I am not 100% certain of how the story will flow and I want my characters to have the possibility to grow and change.

Re-read part 8 of The Story Grid.

FINISHING THE DRAFT

Sprint to the end, my friend, because that is all you can do. You have to go back on all your work and write those skipped scenes. Maybe you don’t want to write them. Why? Are they boring? Tedious? Do you need to do more research?

RESEARCH

The research part of writing can be really exciting and can be done at any point during the process. It can give you a refreshing break, if that is what you need at any given time.

We have so much information at our fingertips that it’s hard not to take it for granted. Make sure to fact check and cross-reference. I’m sure your local library has resources that you can take advantage of. Many libraries now have apps for digital lending.

PANTSERS, PLANNERS, AND HYBRIDS BEWARE

Beware the preemptive numbering beast. Numbering a scene preemptively might provoke the erroneous idea that it is fixed in place—or worse—that it is fixed in the wrong place. I found that I am more successful in my attempts if I don’t number anything until my project is finished and I intend to edit with The Story Grid Spreadsheet.

Beware stopping. Do not stop writing, planning, or researching your story. Everything counts, from reading in your genre to watching a film that you think will inspire you. You will start to notice synchronicities and story elements will start to fit into place.

Beware editing as you write. It is a temptation that you mustn’t succumb to. There is a time and place for editing, but it isn’t while you are writing. I have yet to learn this.

CLOSING

Maybe the crux of the matter is the idea that pantsers and planners can evolve. Knowing your nature, working with it, and then testing the limits of it in the opposite direction seems to be an excellent way to learn and grow, and that is what I propose to you.

What’s great is that The Story Grid can be employed macro to micro and vice versa, depending on what your predispositions are.

LAST WORDS

Analyse stories that you love. Pick them apart and see how they work.

If you’re suffering from writer’s block, look up Steven Pressfield’s book The War of Art about fighting resistance, which is one of the biggest hurdles that creatives must overcome.

Some writers start writing their last scene first, some start in the middle. Try things out and see what feels comfortable.

Please keep in mind that this is just one person’s opinion. My practices might not work for you but I encourage you to keep seeking answers and instruction. Do not despair! You’ve got this.

All the best,

::

SOURCES

Coyne, Shawn. The Story Grid: What Good Editors Know. Black Irish Entertainment LLC, 2015.