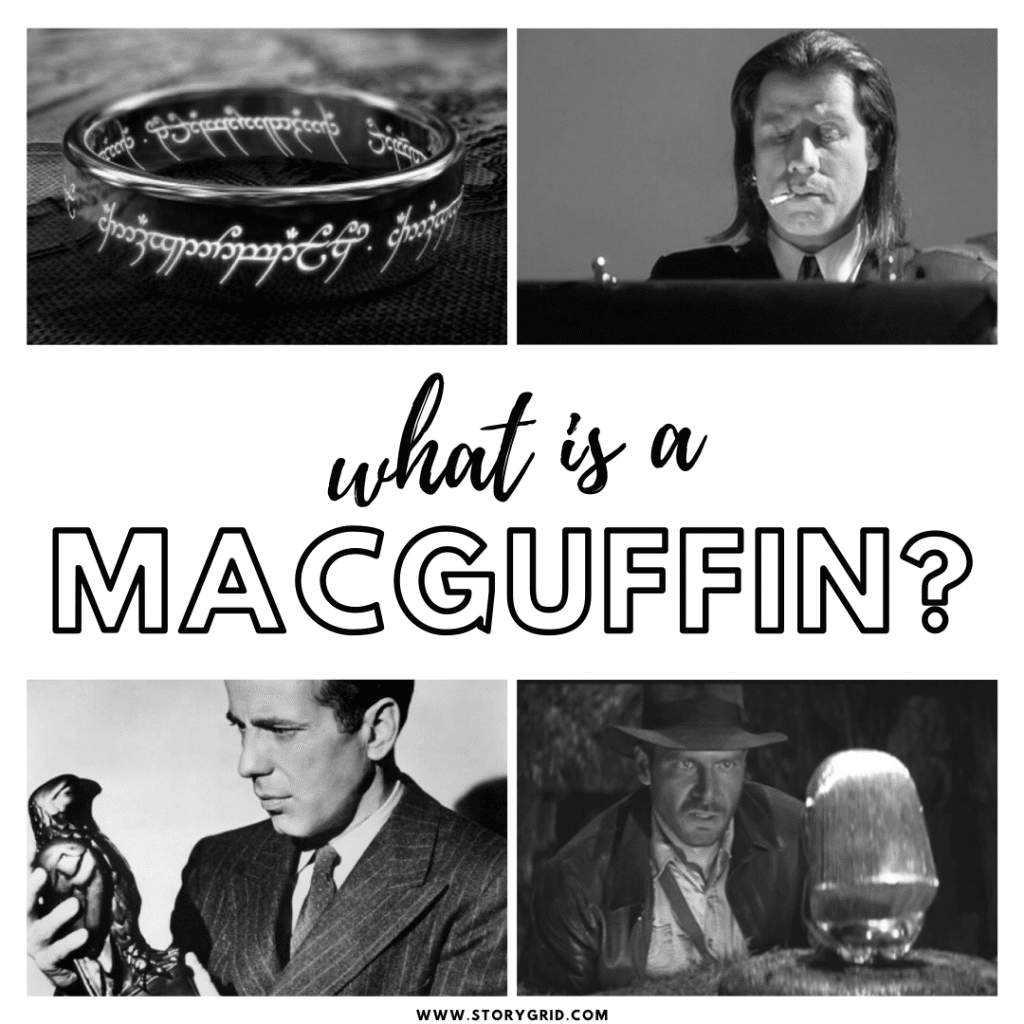

What is a MacGuffin?

In Story Grid terms, the MacGuffin is defined succinctly as the villain’s (or the antagonist’s) object of desire: what the villain wants or needs. But that’s just the starting point to understanding the multifaceted MacG.

DOWNLOAD THE CRIME CHEAT SHEET

The term is associated with British director Alfred Hitchcock, although Wikipedia informs us that it was actually one of his screenwriters, Angus Macphail, who coined the term. However, it is certainly Hitchcock that popularized the word. Hitchcock described it as a particular kind of plot device. In a 1939 lecture at Columbia University, he explained it this way:

“It might be a Scottish name, taken from a story about two men on a train. One man says, ‘What’s that package up there in the baggage rack?’ And the other answers, ‘Oh, that’s a MacGuffin’. The first one asks, ‘What’s a MacGuffin?’ ‘Well,’ the other man says, ‘it’s an apparatus for trapping lions in the Scottish Highlands.’ The first man says, ‘But there are no lions in the Scottish Highlands,’ and the other one answers, ‘Well then, that’s no MacGuffin!’ So you see that a MacGuffin is actually nothing at all.”

In a 1972 interview with Dick Cavett, Hitchcock said a MacGuffin is “The thing that the characters on the screen worry about, but the audience don’t care.”

Earliest Use of a MacGuffin

Hitchcock’s 1935 movie, The 39 Steps, is often cited as one of his earliest uses of a MacGuffin. The protagonist, Richard Hannay meets a woman who tells him that she’s a spy and is then promptly murdered. On the run from the authorities, who suspect him of the murder, Hannay tries to clear his name by finding the enemy spy ring the woman referred to and learning what they want. We don’t learn until the end that they want the plans for a new aircraft, hidden within the memory of a music-hall mentalist named, appropriately, Mr. Memory. But by then we don’t really care. What we care about is Hannay. The plans are just a MacGuffin.

By the time Hitchcock made North by Northwest (1959), the MacGuffin was just a vague reference to “government secrets”.

George Lucas disagreed with Hitchcock, asserting that the audience should care about the MacGuffin almost as much as the characters do. He stated that R2D2 was the MacGuffin of Star Wars, and that he made the little droid likable precisely so the audience would care. The parallel between hiding the aircraft plans inside Mr. Memory’s head and hiding the Death Star plans inside R2D2 is probably not coincidental.

In either case, the MacGuffin is a plot device that keeps the action going, but is really an interchangeable part.

If the MacGuffin isn’t important, then what is?

Let’s take an example. Say you’re writing a Thriller where the MacGuffin is a deadly virus that can wipe out 99% of the human race. Here are some questions you need to answer that will drive the story in different directions.

- Does the Villain already have the virus? In that case it’s the Hero’s job to take it from her and/or destroy it.

- Does the Hero already have the virus? In that case it’s the Hero’s job to keep the Villain from getting it. There must be some reason the Hero is reluctant to or cannot just destroy it.

- Does a third party have it? In that case it’s a race between the Hero and the Villain. Who will get to it first? And what happens when they do?

- Does the Hero get involved because he has expertise in virology or because he’s good at infiltrating master villains’ lairs? Is the Villain a virologist?

Why does the Villain want it? To use it? To trade it for something else?

Now, suppose that, instead of an organic virus, we make it a computer virus that can take down the Internet or take over everybody’s digital devices or some such.

Has anything really changed? No. You still have to decide on the answers to the same questions, and — and this is key — you can make exactly the same choices. There will be technical differences in terminology and the means of infection and so on, but there won’t be any difference in the Hero’s arc, the Villain’s motives or the roles of the secondary characters

The virus is a MacGuffin.

The Title can Illuminate the MacGuffin

Quite often, the story’s MacGuffin is right there in the title.

You want examples? We’ve got examples.

The Maltese Falcon, The Sword of Shannara, The Da Vinci Code, The Pink Panther, The Book of Eli, The Hot Rock, The Matlock Paper, The Bourne Identity (really, you could make a list out of just Ludlum novels), any book or movie titled The ___ Scroll, or The ___ File.

Sometimes the item is part of the title, as in Raiders of the Lost Ark, or any of the Harry Potter books.

Why put the MacGuffin in the title? So that you know right upfront, before you even start reading or viewing, what the story will be about, what the Villain and the Hero will be concerned with. Do you have any doubts about what to expect in Snakes on a Plane?

A Sports Analogy

You can think of MacGuffins in terms of an analogy to sports.

In basketball, the court is divided down the middle. Each team has a basket they’re defending while trying to get the ball in the other team’s basket.

In (American) football, the field is divided down the middle. Each team has an end zone they’re defending while trying to get a touchdown in the other team’s end zone.

In ice hockey, the rink is divided down the middle. Each team has a goal that they’re defending while trying to score in the other team’s goal.

It’s the same story. In a sense, they’re all variations on the same game.

The basketball, the football, the hockey puck are all MacGuffins. What they are doesn’t really matter. What matters is how the basic idea is innovated: the number of people on each team will make a difference in playing the game, as will the size of the playing area and the specific rules and the skills one must acquire.

Or if you really want to innovate, you introduce a Golden Snitch.

The Ultimate MacGuffin

Probably the ultimate MacGuffin is the Holy Grail. The grail is the object sought by various knights in the Arthurian cycle of stories and is purported to have magical healing powers. It is the decision to quest for the grail that is the Inciting Incident of all the knights’ adventures.

Originally just a grail with mystical powers in a romance entitled Perceval, the Story of the Grail, written in the late 12th Century by Chrétien de Troyes, it became a stone in the hands of Wolfram von Eschenbach in his Parzival (early 13th Century), and was later identified with the cup that Jesus drank from at the Last Supper.

In this variation, it has been searched for by everyone from the knights of the Round Table (whether Thomas Malory’s or Monty Python’s) to Indiana Jones to Robert Langdon. Lloyd C. Douglas decided to modify the quest by having his protagonist look for, not the grail, but the robe that Herod Antipas’ guards mocked Jesus with, in his novel appropriately titled The Robe.

In the Arthurian romances, although the knights may be hindered in various ways in their Quest for the grail, there is no villain or adversary who is after the grail for his own ends. In Indiana Jones and the Last Crusade, on the other hand, the grail is what the villains are after, coercing “the Jones boys” to help them.

The MacGuffin is what the villain wants — except when it’s not.

It can be the object of the Hero’s quest.

As we’ve seen in the case of the Grail stories, the MacGuffin can be what the Hero wants or needs in order to solve some problem or attain some end; there needn’t be a villain who is also after it.

In Lorenzo’s Oil, Augusto and Michaela Odone seek a cure for their son’s rare illness. In this case, no such cure exists. The couple has to create the MacGuffin — the Oil in the title.

The MacGuffin can be the villain or force of antagonism.

In Bird Box, the MacGuffin is the — whatever — that causes people who see it to go mad and commit suicide.

At the beginning of the story, we’re intensely curious about what it is that can so radically and destructively alter the behavior of anyone who catches even a glimpse of it. We have many questions: Is it something natural or supernatural? Is it extraterrestrial? Where did it come from? Is it safe to see a recorded image of it? Is it one thing or many?

And the overriding question, What the frack is it?

Some of these questions are answered:

No, it’s not safe to view a recording;

It’s (probably) a multitude rather than a single entity.

But the big question is never answered. And that’s okay.

Somewhere in the Middle Build or Ending Payoff we realize that any answer would be a letdown and at the end of the day irrelevant. Space aliens? Is that all? Angels or demons? Ho-hum. What matters is what it does to people and how they respond to the danger, and those things are shown in the story.

This force of antagonism fits one of Hitchcock’s definitions of a MacGuffin,: “what the audience cares about at the beginning, but not by the end.”

The MacGuffin can be something the villain wants to destroy, rather than possess.

It’s her Kryptonite, her Achilles’ Heel, the thing that can bring her down. This is the case in The Sword of Shannara, which otherwise more or less follows the plot of The Lord of the Rings. In the latter, Sauron wants to recover the One Ring to augment his power, while Frodo and company are tasked with destroying it. In the former, the eponymous Sword is the one thing that can destroy the villain Brona, and it is Flick Ohlmsford’s job to find the Sword and use it for its intended purpose, while Brona wants to destroy it.

But either way, the Ring and the Sword are both MacGuffins.

The MacGuffin can be more than one thing.

It could be a series of objects, each presenting a different and more challenging test or trial to the Hero. Or there could be a kind of treasure hunt, where each object provides a clue to the next one.

In Raiders of the Lost Ark, there are four MacGuffins.

The first one is the golden idol in the opening sequence. Its main purpose is to show us Indie in action and the rivalry between Indie and his nemesis, Beloq, but otherwise doesn’t play a role in the action that follows. It’s a mini-MacGuffin.

The next MacGuffin is the Eye of Ra, the medallion that has the instructions for creating the staff it must rest upon. Next up is the 3D map in the well of Souls. The Eye, placed on a staff of the proper length, casts a beam of light on the map that indicates where to dig.

And we all know what the final MacGuffin is.

Instead of a series of objects, the MacGuffin can be a collection of objects that have been separated and must be brought together in order to be used: the two halves of a medallion; the seven keys to open all seven locks on the door to the hidden chamber; the pieces of a map divided among partners or brothers or kings of neighboring kingdoms.

The MacGuffin can be a person.

Instead of the secret formula, it can be the scientist who developed the secret formula. Or the agent who knows the secret code, or the employee whose retinal pattern unlocks the door, or…

When the MacGuffin is a person like this, they’re really one leg of a treasure hunt for the ultimate MacGuffin. Find the person, find the formula, etc. Mr. Memory in The 39 steps is one such MacGuffin.

The MacGuffin can be the kidnapped child of the king/president/CEO. Or the kidnapped spouse of the scientist who developed the … whatever. Jack Stanfield’s family in Firewall is an example.

In plots of this kind, the person is used as leverage to get the CEO, scientist, etc. to do something the villain needs them to do in order to get the real MacGuffin they’re after.

In both these cases, the person is a means to getting the actual object the villain is after, but it’s also possible for a person to be the real MacGuffin. For instance, they could be the hidden heir to the fortune, or the key witness in a courtroom drama, or the One predestined to overthrow the tyrant. They could even be the protagonist:

That’s right, Neo is the MacGuffin of The Matrix

MacGuffins: They’re not just for thrillers anymore.

In Chapter 32 of The Story Grid: What Good Editors Know, Shawn Coyne discusses the Conventions and Obligatory Scenes of a Thriller, and it is here that he first brings up the concept of the MacGuffin:

“A MacGuffin is the object of desire for the villain. If the villain gets the MacGuffin, he will “win.” Some familiar MacGuffins are a) the codes to the nuclear warhead, b) one thousand kilos of heroin, c) microfilm, d) and in the case of The Silence of the Lambs, the final pieces of skin to make a woman-suit. The MacGuffin must make sense to the reader. It doesn’t necessarily have to be realistic, just believable.”

But MacGuffins aren’t confined solely to thrillers. As we’ve seen in examples above, they can be the object of a quest where there is no external villain, and where the stakes needn’t be Life and Death.

In a Performance story, it’s the prize, the trophy, the championship belt. In a heist or caper, it’s what the crooks are trying to steal.

It can even be the plot device in a Love Story, something that brings the lovers together or separates them, or both.

It’s not difficult to make a case that, in Pride and Prejudice, Mr. Bingley could be renamed Mr. MacGuffin. In the beginning, his arrival at Netherfield is what brings Elizabeth and Darcy together. Later their opposing reactions to Bingley’s and Jane’s mutual attraction is what drives them apart.

In the 1937 screwball comedy Bringing up Baby, there are two MacGuffins that bring Susan Vance and David Huxley together. The first is Baby, a tame leopard sent as a gift to Susan’s aunt, and the second is a rare Brontosaurus bone (not that there are common ones) sent to David, a paleontologist who works at a museum. Both MacGuffins go missing; Baby wanders off, and Susan’s dog runs off with the bone and buries it somewhere. In the course of helping each other find the two MacGuffins, the couple fall in love.

What’s Up Doc? is essentially a remake of Bringing up Baby, except that the dinosaur bone is now a suitcase full of rocks (don’t ask) and there are other identical suitcases that are switched around. MacGuffins all, and all for the purpose of bringing the lovers together.

A versatile device.

Like a gadget in a 3 A.M. infomercial, the MacGuffin is a very versatile device. It can be as nondescript and meaningless as “government secrets” or as heart-wrenching as the protagonist’s fatally ill child, as in 2002’s John Q.

Your Macguffin can be one thing or many. It can be a person (Kaitlin Costello, the witness in The Verdict), a place (the knoll in Tai Pan)), a thing (the Maltese Falcon), or even an idea (the idea of democracy in The Stars, Like Dust).

Does my story have to have one?

Yeah, it does.

Go back over the books you’ve read or the movies you’ve seen. Try to find one without some kind of MacGuffin. Not just your favorite movies or the books everyone loves. Go back to the clunkers, the ones that didn’t work. If they made it into print or onto the screen, you’ll find a MacGuffin there.

As in the sports analogy, you can innovate a MacGuffin that’s been used before. Take the deadly virus example. Alistair MacLean used it in his 1962 novel, The Satan Bug, as did Dan Brown 50 years later in Inferno. Frank Herbert innovated the nature of that MacGuffin in his 1982 novel, The White Plague. In it, a character designs a virus that only kills women. Terrorists killed his wife and daughter and in his grief and madness he decides that if “they” can take his women from him, he’ll take their women from them. All their women.

And there was Stephen King’s little book, The Stand.

Or, instead of innovating a well-used MacGuffin, you can come up with a brand new one, your own personal Golden Snitch. Or Horcrux.

It could even be a breakfast sandwich a certain burglar tries to steal from a certain friendly clown.

However you go about it, remember that the purpose of the MacGuffin isn’t just to have a MacGuffin; in fact that’s never why it’s there. It’s purpose is to drive the action of the characters, to reveal their strengths and weaknesses, their values and principles.

Now go out and give your characters something to worry about, look for, fight over, or help each other get.