👉 Write a book you're proud to publish 👈

Executing Cause and Effect

Last month, we looked at internal genres from the perspective of Friedman’s Framework. Our aim was to distinguish the three main internal genres and twelve subgenres because they can be confusing or, as Shawn Coyne says, “squishy.” From the work of literary critic Norman Friedman and studying twelve Masterworks, we learned that not every character is capable of every internal genre.

More specifically, we found that each subgenre creates a unique, identifiable pattern that provides the experience and emotion a reader expects. The pattern includes these elements:

- The right kind of protagonist with a specific combination of moral character and sophistication of thought.

- The protagonist is exposed to specific external circumstances, including opportunities, challenges, and mentors.

- The external circumstances produce a specific kind of change for the protagonist so that they are better or worse off than they were at the beginning of the story.

From this potent combination, we draft a concise cause and effect statement that describes the essence or pattern of a satisfying story readers recognize and draw meaning from, though they may not be conscious of it.

But how do you create the pattern and execute the arc of the cause and effect statement across an entire story? You use story events and turning points to shift specific Life Values from the beginning of the story to the end, and that is the topic we tackle today.

The Key to Change

If you’ve spent any time in the Story Grid Community, you’ve heard Life Values mentioned pretty often. For our journey today, we need to pin down exactly what’s meant by Life Value Changes.

A Life Value describes a condition or quality of human experience, in other words, a character’s current state of being in life. For example, happy, sad, rich, poor, alive, dead, fulfilled, or unfulfilled. Notice how each value has an opposite, that is, a negative and positive.

Within a story, the Life Values change as a result of Story Events that alter the circumstances. These Events can be external actions (by the protagonist or someone else) or internal revelations. For example

- Before a protagonist is stripped of his rank and title (action), his social status is SUCCESS (initial state). Afterward, because he loses social standing, his social status is FAILURE (new state).

- Before a protagonist learns ghosts exist (revelation), his worldview is IGNORANCE (initial state). After he receives this new information, his worldview shifts to KNOWLEDGE (new state).

Again, the character is in one position (initial state) at the beginning and ends somewhere else (new state). Global Life Values aren’t random, but relate to our universal human needs as explained in Maslow’s Hierarchy. To execute Friedman’s cause and effect pattern effectively, the Life Value shift should unfold incrementally over the course of the story. After all, readers know Rome wasn’t built in a day and protagonists don’t transform in a New York minute.

Defining the Spectrum

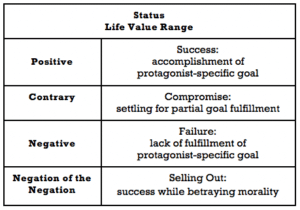

Global Life Value changes occur along a continuum. Each genre has a typical life value range that includes the following:

- Positive value (SUCCESS, UNDERSTANDING, or ALTRUISM)

- Negative value that expresses the opposite (FAILURE, LACK OF UNDERSTANDING, SELFISHNESS)

The Life Value spectrum contains two other main points:

- Contrary value, which falls between the positive and negative values (COMPROMISE, COGNITIVE DISSONANCE, SELF-INTEREST)

- Negation of the Negation, which is worse than the negative (SELLING OUT, LACK OF UNDERSTANDING MASKED AS UNDERSTANDING, SELFISHNESS MASKED AS ALTRUISM)

Combined these points represent a full spectrum: Negation of the Negation to Negative to Contrary to Positive. Additional Life Values exist within this spectrum, allowing the writer to articulate subtle changes in the protagonist for the subgenre and story. We show these values in action in our Masterworks below.

Defining the Arc

In order to create the cause and effect pattern, Life Value changes move in a specific direction along the value spectrum. This may be from positive to negative, negative to positive, or sometimes even from negative to positive to negative.

The progression of scene-to-scene Life Values may vary from story to story within a genre, but the overall pattern has specific features. At this point, without viewing multiple masterworks for each subgenre, we cannot definitely say what the exact pattern is, however from Friedman’s cause and effect statement we can deduce certain features.

For example, Morality-Redemption stories must begin in the realm of SELFISHNESS and end with ALTRUISM, or it isn’t a Redemption story. Status-Tragic begins with a version of SUCCESS and ends with FAILURE. Worldview Disillusionment, however begins in negative territory at BLIND BELIEF but moves to the positive at JUSTIFIED BELIEF and ends with another negative value DISILLUSION.

Examining the Masterworks

One final point before we dive into the Masterworks. Writers ask why we sometimes use movies instead of books as examples, since the majority of Story Grid community members are trying to write novels. The answer, quite simply, is we can’t read twelve novels as quickly as we can watch twelve movies.

Our goal with this series is to help you understand and execute the Internal Genres, so you can write a better novel. To do that well, we all need to be able to experience the same stories that demonstrate the principles. By watching movies, you can experience all twelve stories for less than $60 and 36 hours. Now that’s a masterclass if there ever was one. It certainly has been for us.

But also, we want to emphasize that storytelling is storytelling. Movies are a rich resource of well-executed stories, as we’ve found on the Story Grid Editor Roundtable Podcast, and books and movies are similar in more ways than they are different.

The key is to consider how these two mediums are different. If you use a movie as a masterwork, ask yourself, What would this look like in writing? How can I adapt this aspect to my story?

With that in mind, here we go.

Status

Status Stories concern the protagonist’s quest to rise in social standing, as well as the price they pay to do so. These stories explore social mobility and the nature of success.

The Life Values at Stake are SUCCESS and FAILURE. The movement of the narrative depends on how the protagonist defines SUCCESS. Their best chance for a positive result happens when, with the help of an effective mentor, they adjust their goal to be reasonable in light of their circumstances. If the goal is too ambitious, they risk FAILURE or SELLING OUT by betraying their morality. If the goal is not ambitious enough, they risk SELLING OUT because they appear successful but don’t fulfill their potential.

We create the typical range for a Status Story by adding the contrary and negation of the negation values. In analyzing the four Masterworks, I found it useful to connect the typical Life Values to the protagonist’s specific position within their environment.

Sentimental

Friedman’s Cause & Effect Framework: When a sympathetic protagonist, with a steadfast will but naive worldview, encounters a challenge or opportunity and has a supportive mentor of high moral character, he can rise in social standing.

To create a Status Sentimental Story, the Life Value progresses from within negative territory (FAILURE or SELLING OUT) to SUCCESS, when the protagonist chooses to reject the world they sought to join.

Masterwork: Rocky, the 1976 film written by Sylvester Stallone and directed by John G. Avildsen.

Beginning Hook

Rocky, a once-promising amateur boxer, loses his private locker at his gym because Mickey, the gym owner, tells him he’s no longer a contender and fights only “bums.” Rocky comes to realize that Mickey is right.

Rocky begins the story in a state of SELLING OUT because he wins his fights by taking on opponents who are bums. He chooses goals that are so low, he can appear SUCCESSFUL, but he’s FAILED to pursue his potential. He falls in social standing at the gym when his belongings are put on “Skid Row.” As the Beginning Hook comes to a close, he recognizes that he’s a hypocrite for advising other people to take risks because he doesn’t follow his own advice. With this awareness, he progresses in a positive direction toward FAILURE.

Middle Build

Rocky accepts the challenge to fight the heavyweight boxing champ, Apollo Creed, and Mickey’s help as his manager. He trains steadily and follows Mickey’s advice.

Rocky begins the Middle Build in a similar state of FAILURE, but quickly begins to take risks to restore his status as a contender and live up to his potential. The Middle Build ends in a state of COMPROMISE because he’s changed his goals to something more ambitious, but his fighting is still sloppy and not good enough to win.

Ending Payoff

The night before the fight, Rocky realizes he can’t win, though he’s tried his best. He changes his goal to “going the distance” with Creed because no one’s ever done that against him. Rocky finishes fifteen rounds, and though he loses the fight, the decision is split.

Rocky begins the Ending Payoff in a state of COMPROMISE because his goal is unreasonable, but in the end, he achieves SUCCESS by rejecting the inappropriate goal and adopting one that is a challenge yet within his grasp.

Additional Thoughts about the Story Arc

Rocky, like other Sentimental protagonists, has a steadfast will, which means he has the potential to achieve SUCCESS if only he can focus on an appropriate goal or definition of SUCCESS. The Life Values shift incrementally in a positive direction as he listens to his mentor and understands what his goal should be (not too low, not too high), then uses his will to do what’s necessary to achieve it. SUCCESS becomes going the distance against a worthy opponent, FAILURE is being a bum by not taking risks in pursuit of a goal, and SELLING OUT is pretending to be SUCCESSFUL while being a bum.

Click here for all Status subgenres.

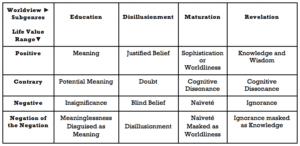

Worldview

Worldview stories focus on the way cognitive dissonance upsets the balance of a character’s life, requiring a shift in their view of reality.

The Life Values at Stake are expressed as a form of UNDERSTANDING and MISUNDERSTANDING, but the specific type of understanding varies with the subgenre and can be delineated as follows.

Revelation

Friedman’s Cause & Effect Statement: When a protagonist, with well-developed will but lacking in essential facts, experiences doubt about their circumstances which leads to a revelation of a shocking truth, they can make wise and appropriate decisions.

In order for a Revelation Story to work, the Life Value change must progress from the negative value of IGNORANCE to the positive value of KNOWLEDGE.

The precise negative opening value may vary, either IGNORANCE or IGNORANCE MASKED AS KNOWLEDGE, but it must progress to KNOWLEDGE. From there, the Protagonist may progress to WISDOM (the informed application of KNOWLEDGE) or not.

Masterwork: The Sixth Sense, 1999 film written and directed by M. Night Shyamalan.

Beginning Hook

Malcolm Crowe, a revered child-psychologist, is shot in his home by his former patient, Vincent, whom he failed to help as a young boy. The next fall, Malcolm meets a new patient, Cole, whose condition mirrors Vincent’s.

The Life Value begins at IGNORANCE MASKED AS KNOWLEDGE: Malcolm doesn’t know his expertise has already failed a child. When Vincent appears in his home and tells him, Malcolm shifts from MASKED IGNORANCE to IGNORANCE. He doesn’t know why he wasn’t able to help Vincent, only that he failed him.

Middle Build

Malcolm works to slowly win Cole over, and Cole tells him his biggest wish is to not be afraid anymore. He finally admits to Malcolm that he sees dead people.

Malcolm begins in IGNORANCE, not knowing the missing piece to helping Cole. At the midpoint, Cole tells him he sees dead people, but that conflicts with Malcolm’s worldview, and the Life Value moves to COGNITIVE DISSONANCE. Losing all hope of helping Cole, Malcolm nearly gives up until he discovers the truth about Vincent—that he saw dead people too—and the Life Value shifts to KNOWLEDGE.

Ending Payoff

Malcolm helps Cole overcome his fear by helping the ghosts. Malcolm returns home only discover the truth about himself—that he died the night Vincent shot him.

With the KNOWLEDGE—that ghosts are real—Malcolm has the missing piece to help Cole overcome his fears. Cole in turn becomes a conduit of knowledge for others: ghost girl’s father, his own mother, and Malcolm. When Malcolm discovers the final Truth about himself—that he is a ghost—he now has everything he needs. By accepting the truth and making a positive choice, his Life Value moves to WISDOM.

Additional Thoughts on Story Arc

Malcolm’s revelations are progressive: he failed Vincent, Cole sees ghosts, ghosts are real, ghosts need help, and ultimately that he is ghost. These progressions move with the Life Values. We can clearly see the convention of following the clues in the global Worldview-Revelation story, but they may manifest differently when acting as co-pilot to a global External Genre.

Click here for all Worldview subgenres.

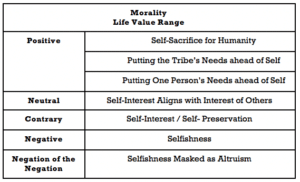

Morality

Morality stories focus on a single protagonist whose inner moral compass actively changes along a spectrum that runs from corruption to virtue. They determine their own fate through their choices and actions.

The Life Values at stake are SELFISHNESS and ALTRUISM. The subtleties of the inner moral compass can be further delineated by motive, expanding the full Life Value range as follows.

Redemption

Friedman’s Cause & Effect Statement: When an unsympathetic protagonist, with strong will and sophisticated state of mind, experiences a seemingly impossible challenge through which they recover their inner moral compass, they make a selfless choice for others and are rewarded.

To create a Redemption Story, the Life Value change must progress from the negative value of SELFISHNESS to the positive value of ALTRUISM.

The opening value should be the negation of the negation, SELFISHNESS MASKED AS ALTRUISM and must progress to some level of ALTRUISM (i.e., selfless sacrifice) either for one person, their tribe, or all humanity.

Masterwork: Kramer vs. Kramer, 1979 film written and directed by Robert Benton.

Beginning Hook

Ted Kramer’s depressed wife, Joanna, leaves him to raise their young son, Billy, alone, interfering with his high pressure job in advertising.

Ted’s life value begins at SELFISHNESS MASKED AS ALTRUISM—he defends his obsession with his career as a sacrifice he makes for his family. By the end of the BH, Ted choose to keep Billy with him, so Ted’s desire (to care for his son) is aligned with the Billy’s needs (to be cared for). This brings the life value to Neutral when SELF-INTEREST ALIGNS WITH THE NEEDS OF OTHERS.

Middle Build

Ted struggles to balance home and work but discovers a new bond with his son, until Joanna returns 15 months later wanting Billy back.

Ted’s Life Value progresses from NEUTRAL to a form of PUTTING THE NEEDS OF ONE PERSON AHEAD OF SELF by the Midpoint. Billy is injured at the park, and even though the doctor tells Ted it’s hard for parents to watch, Ted remains with Billy during while his wound is stitched up. Once Joanna re-enters the picture, Ted defaults to SELFISHNESS, wanting to keep Billy to himself and denying the needs of anyone else.

Ending Payoff

Ted and Joanna endure an ugly trial that Ted ultimately loses. Ted chooses not to appeal and readies his son to move in with Joanna.

Ted faces the ultimate test with regard to his SELFISHNESS when he must choose whether to pursue the appeal and put Billy on the stand. By choosing not to appeal, he makes a sacrificial choice to deny his own Want for the Needs of his son, bringing us to his ultimate Redemption value: PUTTING THE NEEDS OF ONE PERSON AHEAD OF SELF.

Additional Thoughts on Story Arc

It should be noted that although we cite the same terminology of PUTTING THE NEEDS OF ONE PERSON AHEAD OF SELF at the Midpoint, the sacrifice Ted makes to stay in the hospital room with Billy is minimal/temporary compared to the sacrifice he makes to allow Joanna to win at the end. A Redemption protagonist may rise to a level of sacrifice along the way, but the ultimate act must be demonstrated at the Story’s Climax.

Additionally, it’s important to define SELFISHNESS and ALTRUISM relative to a person, a tribe, or humanity. In Kramer vs Kramer, Ted’s Life Values are in relation to his family, and most specifically his son. He begins as selfish in the eyes of his family but selfless in the eyes of his boss. As the story progresses these values trade places: he is selfless toward his son but his boss sees him differently, to the point of firing him. This “defining the scope” for the Life Values is essential.

Click here for all Morality subgenres.

A Writer’s Worldview Revelation: The Truth You Need

Guess what? Everything we’ve covered in Internal Genres part 1 and part 2 relates to the first of the Editor’s Six Core Questions: What’s the genre?

Friedman’s Framework describes the specific change to the specific protagonist that answers that question for the internal genre. Once you determine the genre, you’ll know the Life Value at Stake for the pattern. To create the arc that represents the pattern, the Life Value must change along the spectrum in a specific direction and incrementally through Story Events.

Which Story Events, you ask?

The answer is found in the second of the Editor’s Six Core Questions: What are the obligatory scenes and conventions for this genre?

So guess what’s next?

Internal Genres: Part 3, where we will explore how to execute the Life Value shifts through the Obligatory Scenes (and Conventions).

Got Your Masterwork?

If Internal Genres: part 1 didn’t convince you to choose a Masterwork, we implore you to cross the threshold today. This is the key to your own Worldview-Revelation plot where you will uncover deeper KNOWLEDGE to apply to your own story, moving the Life Value of your writer’s journey to WISDOM.

In fact, if you allow yourself to become immersed in a Masterwork and don’t feel your story skills level up, we will eat our proverbial hats.

So get out there, watch some movies, read some books, and embrace this Controlling Idea:

Wisdom triumphs when writers intentionally seek the truth they need

and use it to express their gifts in the world.

Check out the complete analysis of Masterworks for the Status, Worldview, and Morality subgenres.

In case you missed it, you can still download Friedman’s Framework and access our Internal Genre Elements.