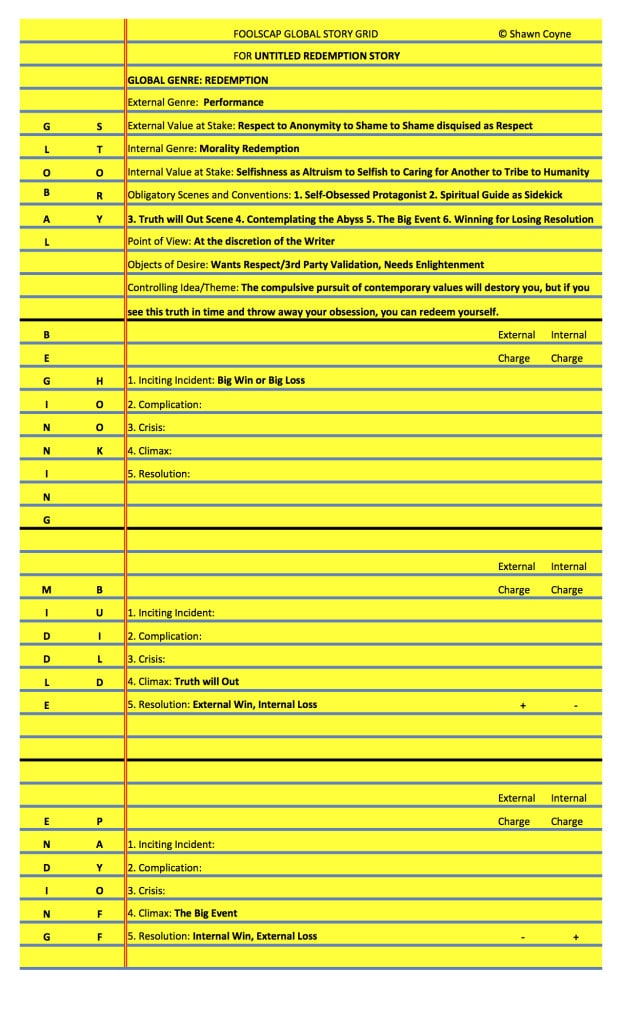

On our Foolscap Global Story Grid for our Untitled Redemption Story we’ve reached the place to write down the conventions and obligatory scenes for the Redemption/Performance combo plate of External/Internal genres.

Before I didactically launch into them, though, let me first put forth this:

Writing and its partner in crime, Editing, is extremely difficult. And because they are arts, they’re very personal.

What works for an Editor and Writer like me…may or not work for you. And the interpretations I have about specific works and even my entire methodology—from Genre to Foolscap to Spreadsheet to Story Grid—is extremely specific to the way I work. And think for that matter.

As a friend of mine David Leddick wrote, I’M NOT FOR EVERYONE, AND NEITHER ARE YOU. What that means is that when I decided to present the way I work and think as a means to help others write and edit, I knew that I wouldn’t be able to reach everyone with every tiny detail. In fact, I’m still fitzing and futzing with many of them myself.

I’m a compulsive personality and I approach my creative work in much the same way I approach cleaning a kitchen counter. First I go broad and take inventory of the entire landscape (Genre), then I divide the landscape into three parts and clean up the big stains on each as best as I can (Foolscap), then I go to the square inch and make sure I didn’t miss anything (Spreadsheet).

And finally, I’ll step back and take in the entire project before calling it quits (Story Grid).

You may disagree with some of my analytical decisions—Is the value at stake in a Redemption Story really Altruism? Are human beings even capable of Altruism?

Or even some of my global theories—Is Performance really a Genre, or is it just some random BS Coyne came up to categorize a bunch of Stories he couldn’t easily figure out?

The important thing about all of this stuff is to think long and hard about all of it. In any way you choose.

Why?

Because writing and editing requires two skill sets—Macro and Micro craftsmanship. The Story Grid is about taking the very real principles of the Macro and Micro of Storytelling and boiling them down to practical tasks. You may not buy into my suggested methods lock, stock and barrel. But there is no denying that they are built upon a concrete/steel-reinforced foundation of Story scholarship.

I’ve been editing stories for decades, obsessively reading other Story nerd writers from Plato to Mckee and applying what I’ve learned successfully in the marketplace. I’ve edited scores of bestsellers and worked on hundreds of financially successful titles (and I believe artistically successful as well). I’ve worked on many books that just didn’t find an audience too.

What I know is that every writer and editor has his/her own system. Just like I do.

Steven Pressfield doesn’t use every single tool from The Story Grid to write his fiction or nonfiction. He’s got his own method and it works great for him. But I will tell you that when he gets stuck, he has zero problem spreadsheeting or re-Foolscapping or even going the whole nine yards and Storygridding his manuscript from scene one through scene seventy-one to make it work.

He’s a pro. Pros will do what it takes to get it right….as right as it can be before letting it go. Because, deep down they know the work isn’t all about them. Once they put it into the ether it’s out of their hands.

The Story Grid methodology is about finding a common language. A vocabulary that the writer and the editor can share. So that their partnership to make Stories the best that they can be is efficient and rewarding, rational and as non-combative as possible.

Okay, so let’s keep moving down our Foolscap Global Story Grid for an Untitled Redemption Story.

The first convention of a Redemption story is to introduce your protagonist in a serious state of selfishness. Remember that we are going to make our protagonist change from a self-obsessed person to one who sacrifices for the good of another or a group.

So when first introduced, we want a protagonist in heated pursuit of one or more of the following: success, fortune, fame, sex, power… Those pursuits are from our global controlling idea for a Redemption Story.

This doesn’t mean that he’s necessarily Ebenezer Scrooge (if you want to understand Redemption Story, A Christmas Carol is a great place to start), hording money etc. It just means that he is totally self-obsessed.

I would also add the protagonist obsessed with their “victimhood” in this description, those Eeyore-like figures who have convinced themselves that the world is against them, that they’re doomed to burn their days as perennial losers.

A quick side note here:

Many of the Internal Genres meld. That is, they are open to interpretation.

Some would view A Redemption Story as an Education Story or a Maturation Story or a Revelation Story. I could make very good arguments that Rocky is not a Redemption Story, but rather an Education Story. Tender Mercies is another like that. I classified Tender Mercies as Education Story in the book, but I also see it as a Redemption Story too. It’s both.

Rocky’s view of the world shifts from negative to positive (indicative of an Education Story) as surely as his personal evolution moves from disgraced down and outer muscling for the mob to honorable fighter (the Redemption arc).

The important thing is to clearly think about which of these Internal Genres you as the creator want to dedicate your attention. As long as you are specific about what you wish to accomplish, the fact that someone may see your work as a Maturation Story instead of your intention of creating a Revelation plot makes little difference.

The beauty of Story is that the audience brings their personal histories to the experience and finds things inside the tale that the writer had no idea were in there. Embrace that magic. Don’t argue with it. Once you release your Story, it’s no longer yours. It’s everyone’s.

Just be very clear and specific with your work and if you do it well, universality will result, as evidenced by the nuanced ways your readers interpret what you’ve written.

Here are some examples of Stories with Redemption Protagonists.

Rocky : At the beginning of the Story, Balboa is a lovable if whiny loser, put upon and pathetic. His plight is everyone else’s fault and the world has no use for him. He seems resigned to his fate living in a dump and unsuccessfully trying to get a rise out of the girl behind the counter of the pet shop.

Kramer vs. Kramer: Ted Kramer is a big shot advertising executive on his way up the corporate ladder. He’s got all of the accoutrement, a pretty blonde wife and a cute as a button kid. But he’s all about #1. The people closest to him are possessions, not sources of joy, comfort, or pain.

The Color of Money: Eddie Felson is a slick liquor salesman who, for a giggle, backs pool hustlers on the side. He does it to amuse himself and could care less about anyone or anything beyond his private “Fast Eddie Felson” code.

The Verdict: Another great Paul Newman role (he played Fast Eddie too). Frank Galvin is an alcoholic ambulance chasing lawyer with a self-hatred so intense he’s blind to any and all beauty in the world.

The second convention of a Redemption story is that there is at least one character who serves as a spiritual guide/sidekick, someone who helps the protagonist move from living completely inside their own universe to someone engaged in the greater world, capable of deep caring for others.

The primary sidekick for Rocky is Adrienne, his love interest, but Mick and Paulie serve in that role too, both as cautionary figures. That is, if Rocky doesn’t change, he’ll end up like a cross between Mick and Paulie. Not pretty.

The primary sidekick for Ted Kramer is his son Billy. Billy could care less about how much money his father makes. He just wants his attention and love. Another sidekick is the character played by Jane Alexander, Margaret Phelps. Phelps is Ted’s wife’s friend who encouraged her to leave Ted. But she and Ted become friends as Ted discovers just how deeply important it is to take care of someone else.

Fast Eddie Felson’s sidekicks are reflections of himself. Fast Eddie first appeared in Walter Tevis’s Maturation/Performance masterpiece, The Hustler. The Color of Money was Tevis and Richard Price’s sequel.

The first sidekick is the Tom Cruise character, Vince, the naïve and peculiar nine-ball savant—the ghost of Felson’s Xmas Past. The second is the character played by Mary Elizabeth Mastrantonio, Carmen—the Machiavellian schemer—Felson’s ghost of Xmas Present.

Going on an extended road trip with these two, Eddie sees just how ridiculous his way of life is. He rediscovers his love of the game and in a subplot his love of the woman he’s been keeping at arm’s length on the side. It has one of the great all time endings for men of a certain age, of which I now include myself…I’m back Kid! And then the thunder crack of a perfectly struck break. Goosebumps.

On to the Obligatory Scenes.

The big one is what I call the Truth will Out Scene, which is a requirement for all of the Internal Genres—Worldview (Education, Revelation, Maturation and Disillusionment), Status (Sentimental, Pathetic, Tragic, and Admiration) and Morality (Punitive Redemption and Testing).

For the Redemption Story, this is the critical moment when the tumblers inside the protagonist’s head finally align and the lock that’s been holding back the deep truth of his life (being alone is hell) clicks open.

Obviously, this scene is the crucial moment in the Global Story…when the protagonist comes to understanding that he’s has been absolutely wrong about the ways in which he’s lead his life.

It’s the Christmas Carol scene when Scrooge realizes what a putz he is. In his third visit with the ghost of Xmas future, the old man visits his own grave and understands that he’s wasted himself being a miser.

Without a clear and cathartic TRUTH WILL OUT scene, your Redemption Story simply won’t work. Crack this puppy and the rest of the story will pretty much write itself.

You’ll notice that I slotted the TRUTH WILL OUT scene as the Climax of The Middle Build on my Foolscap. While you can put it just about anywhere (you could even foreshadow the whole story and use it as a prologue/first scene to grab the reader/viewer immediately), this is traditionally the place where we expect to read/see this scene.

It’s the moment when Rocky realizes that just surviving 15 rounds with the champ and going home to Adrienne is all he needs. Or when Fast Eddie Felson gets hustled by Amos (Forest Whitaker) in the Color of Money, something clicks for him. He’s being hustled and he doesn’t like it one bit.

The next obligatory scene is what I call CONTEMPLATING THE ABYSS. (Which is essentially the ALL IS LOST MOMENT) This is a scene when the protagonist, who now sees the truth about his life, has to understand just what he’s going to lose if he adopts the new way of living.

Casting aside the material baloney of life in favor of connection to other human beings requires real loss. And it ain’t small loss either. We need as readers to understand just how big a choice this is. It’s often the difference between wealth and “barely getting by.” If you get stuck here, I think it’s a good idea to think about Maslow’s Hierarchy of Needs. In order to get connection (love) the lead character must lose something on that pyramid that he’s extremely reluctant to give up. The choice has to be as difficult as a drug addict walking away from his fix.

The last essential obligatory scene for a Redemption/Performance story is THE BIG EVENT. This is the moment promised by the beginning hook.

Rocky fights Apollo Creed.

Fast Eddie plays for himself in the 9-ball Tournament in Atlantic City.

Ted Kramer fights for his son in court.

Frank Galvin’s summation in The Verdict.

I would even wager that all of the other possible combo platters you could create with the other external genres require a Big Event if you are using the Redemption Internal Genre and it’s controlling idea.

I mentioned Gran Torino in my last post, which uses the crime genre to flavor its redemption Story. Clint Eastwood sacrifices himself at the end of the movie to save his community. That’s a big event.

And pretty much all War stories have a redemption element inside them (Dirty Dozen). And as you know War Stories all build to the Big Battle at the end. Is there a bigger event than combat?

Lastly, the final must have convention for the Redemption story provides irony and solidifies the controlling idea that we’ve decided to reverse engineer.

The protagonist must lose The Big Event, but win the internal battle. A Redemption Story must have a “winning for losing” resolution.

Now obviously, after you’ve outlined how you are going to abide these conventions and obligatory scenes, you need to make sure that you’re just not “painting by numbers.”

A reader or an audience is so deeply immersed in the Redemption Storyline that you cannot just hit your marks and deliver a great story. You must innovate these conventions and obligatory scenes. You must always be on the lookout to counter the anticipations of the audience.

That is, you must always surprise them. If you don’t, you’ll lose them.

Rocky doesn’t go into the ring and take a beating for 15 rounds. There are times in the fight when we actually think he’s going to win. He knocks down Apollo Creed and breaks his ribs. This twist happens shortly after Rocky realizes the night before the fight that “he can’t win.” But shit! Maybe he can!

My advice is to bang out your ideas quickly and give yourself plenty of slack when you’re just spit-balling these scenes and conventions. Create your own private writers room in your head.

One guy in there has a solution for everything. While another takes great pleasure in beating down every single one of his what ifs. And just when all hope is lost, another guy in your head (your own private internal show runner) saves the day by inventing something completely awesome using the deep knowledge of the world you are writing about.

The trick about innovation is to use your insider knowledge about the world you are writing about to your advantage.

For example, I know book publishing in microscopic detail. I know it’s history, its culture, its pros and its cons, its charlatans, its heroes, its pathetic hangers on, its unsung leaders, its corporate overseers, etc. etc.

If I were to write a Truth Will Out scene using my deep understanding of book publishing, the thing I would do is present a scenario to the audience that they would think was a positive (or a negative) intuitively. And then pull the rug out from under them with my knowledge base.

For example, I might have a young editor discover a brilliant new voice in fiction. She fights like hell to be able to acquire and publish the work, and then almost goes crazy editing it until she’s certain it has everything it takes to be a huge success. With monomaniacal zeal, she pressures and pushes the marketing and publicity departments to take notice of her pet project.

Reluctantly, her colleagues come on board. Everyone in the house pitches in. And the book becomes a huge commercial success.

The Truth Will Out scene comes on a late Wednesday night when The New York Times bestseller list gets faxed to the major publishers 10 days in advance of its publication.

Every editor with a book-in-play at the Big Five houses stays late on Wednesday night.

The list comes in and her book is #3. The publisher gives her a hug. The production manager freaks out because they don’t have enough stock in the warehouse. But our editor?

She’s devastated.

This moment (which the audience won’t really understand until it plays out) is this editor’s TRUTH WILL OUT scene. What happens, being #3, makes her understand that her life is a mess, that she’s missed the point of why she’s an editor in the first place, that everything she’s been working for is bullshit.

The audience doesn’t know why this information is so devastating, until they get her CONTEMPLATING THE ABYSS SCENE. And after the contemplating the Abyss Scene, they won’t know what will ultimately choose to do in the Big Event scene, which could be the National Book Awards or BEA. (There’s a reason why book publishing fiction isn’t all that popular…the stakes just aren’t that high…even for the people in the business).

Why?

Because the readers doesn’t know the specificity of the book publishing world like the writer of the Story does.

But if the writer does his job well, by the end, the reader/audience will feel like they could walk into Random House and land an editorial job in one interview. Admit it, after you saw Rocky, you thought with the right training you could do okay for yourself in a ring…not heavyweight champ well, but maybe a round or two with a golden gloves level boxer…

Innovating these genre forms requires deep knowledge of unique worlds. Don’t make the mistake of writing generic crap that just abides the requirements of the form. It won’t work. It will be cliché. The reader/audience will know what’s going to happen within five minutes of reading or viewing.

The only way to keep the mystery/suspense/dramatic irony of your Story moving forward is to be an expert in the world in which your characters are in play.

Conventions and obligatory scenes are like the legs, backrests, and seats of chairs. Without them, you don’t have a chair. But if your chairs are just like everyone else’s, no one will want to sit on your furniture.

For new subscribers and OCD Story nerds like myself, all of The Story Grid posts The Story Grid Bonus Material posts and Storygridding The Tipping Point posts are now in order on the right hand side column of the home page beneath the subscription shout-outs.