“We need another chapter, don’t we?”

We were on the last leg of revisions, with a deadline at play, and the gap had just become clear. Painfully so. A serious pivot in the author’s life required a serious pivot in his Big Idea book (or Big Idea-lite, if you’re exploring that concept with me), and we didn’t have much time to do it. After a couple hours exploring possibilities, we’d found a way to pull the threads together, but it required another chapter. One we needed to get right—and we needed the chapter outline fast.

Theories about refining our work are fun to play with when time isn’t a factor, but when you’re on deadline, all that matters is one key skill: how to draft a nonfiction chapter, both quickly and effectively.

There are many reasons a deadline can pop up in your writing timeline, and it’s not easy to be your best creative self under the constraints of time and external pressure.

Then again, sometimes the pressure we’re up against is needed. Having too much time and too much room to explore can lead us to spin out in theoretical possibilities, trying to over-sharpen our ideas down to a nub before they ever have a chance.

We’ve talked about the commandments of nonfiction storytelling, and how the different levels of quadrants can give us fresh angles on the way our work flows. And as all storytelling commandments go, these concepts apply at global, sequence, scene, and beat levels.

But it’s less than productive to try to spin through a rotation of the quadrants at every level during the early stages of writing. At their highest potential, Story Grid editing tools are meant to refine writing that doesn’t work, so if you’re using them to over-plan (and never write), they can quickly become a tool of resistance.

That said, there are ways to use the core principles at a drafting stage, and that’s exactly what my client and I did to get him a full chapter outline in just ten minutes of conversation. Let’s convert that to a five-minute exercise to get you a draft-worthy chapter outline for your nonfiction project.

Quick Caveats before We Begin

One thing to know about Story Grid methods is that they aren’t shortcuts. They can feel like shortcuts for fiction, since they get to the heart of problems that can often take years to surface. But there is a temptation in self-published nonfiction—especially business how-tos—to productize our work.

Maybe you want to leverage your book for a pivot in your career, or publish your memoir because “it’s just time.” And if it’s your expertise, your story, your life—that means you can just knock it out, right? Draft over the summer, write your book during quarantine, tell your story before the year is up…time is money, after all. Carpe diem, etc.

Before I move any further on a post promising quick results, I want to be clear on what those results are: we are just making a draft here, and the real thing is still going to take work.

Not every nonfiction book requires five years of new research to complete (though some certainly do), but every book deserves the care and attention of time, revisions, and the outside perspective of an editor before it’s released into the wild. That’s what our Story Grid tools and services are for.

That is not what this blog is about.

If you’re cutting corners, you’re cutting the power to your message.

By 5-minute chapter outline, I mean exactly that. You’re going to use the constraints of time to break through resistance and get to a chapter outline that works well enough to draft from. Quick and dirty drafts give you something to play with—something to tinker on, using those editing tools for their intended purpose.

We’re not worrying about beats. We’re not worrying about baking in dramatic irony or punching up the emotional arc. We’re just getting a map down before our analytical brains can muddy it up.

The 5-Minute Nonfiction Chapter Outline

The basis of this exercise is to make quick, gut decisions on the five nonfiction storytelling commandments that work well enough to get started. Like a brain mapping or meditative journaling exercise, the constraints of a literal timer help you get down to what you know to be true, before you have a chance to rationalize it away.

I’ll be honest: I don’t have a miraculous breakthrough every time I put lead to paper while a timer is running—especially if I’m journaling or dabbling in fiction. Sometimes those kinds of exercises create a bunch of gibberish on the page.

But here’s the thing about nonfiction: this stuff lives in you. Even if it’s an author-protagonist Big Idea journey that you’re going on, the question that sent you on that journey is a brain worm that won’t leave you alone.

The only thing that really trips us up here is our tendency to overthink.

That, or we are chasing someone else’s brain worm.

The more authentic the book’s concept is, the more effective this exercise will be.

Then, all you’re going to do is set 5 one-minute timers, that will ultimately get you to an outline that hits all five storytelling commandments:

- The inciting question/concept

- The turning point revelatory insight

- The crisis about how to apply that insight

- The climax connection to the larger question/concept

- The resolution that integrates the chapter’s concept/answer into your or the reader’s world

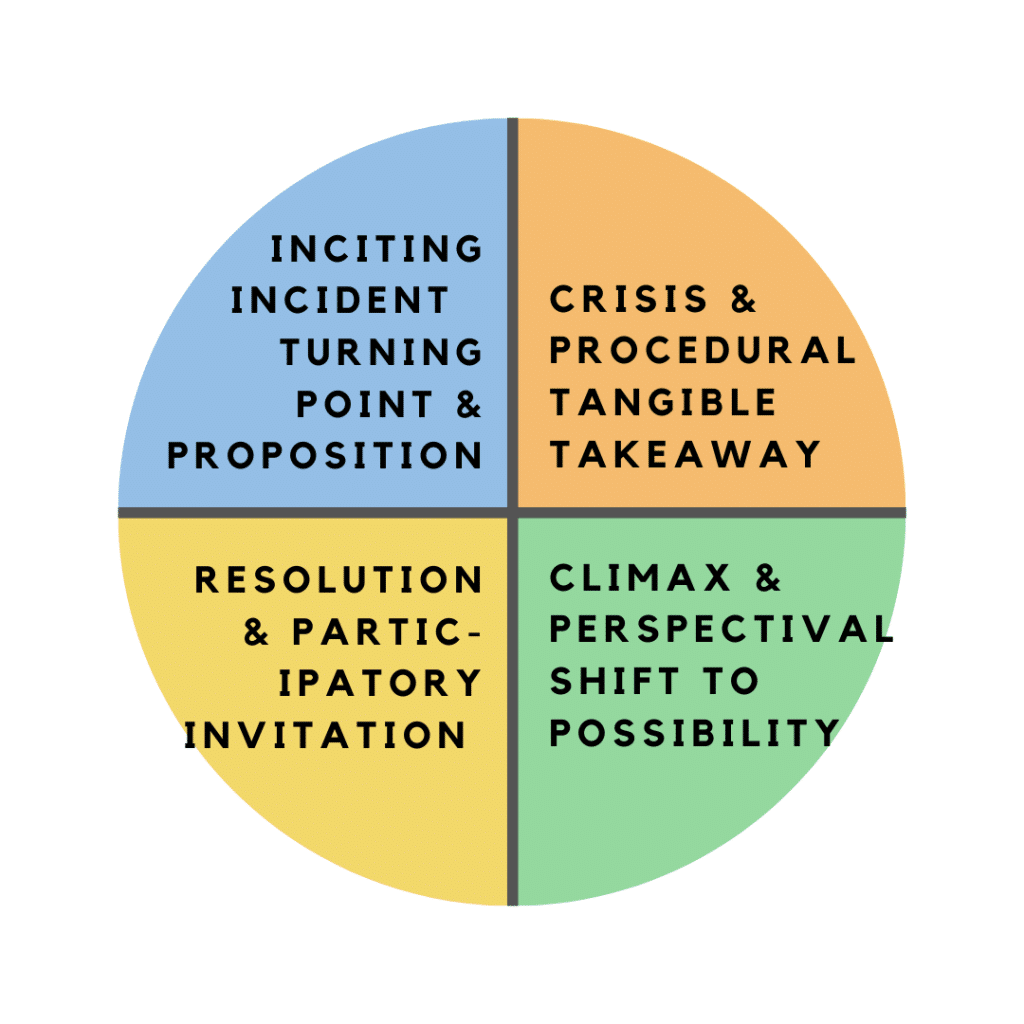

Or, if you’re working from the four quadrants:

- The proposition of a new concept/question

- The procedural path to Do Something with that concept

- A perspectival demonstration of What’s Possible With that concept

- A participatory invitation to integrate that concept (and become ready for the next)

We’re going to use the principle of both here, so get out your notebook and a pencil and write:

(II) 1.

(TPC) 2.

(Crisis) 3.

(Climax) 4.

(Resolution) 5.

Then stop writing.

#1 is the Inciting Incident, and will include some propositional content. #2 is the turning point progressive complication, which will be achieved through a heavy dose of propositional content. #3 is the crisis, and with #4 (the climax) will tend to be procedural and perspectival—what do I do with that information, and how do I know it’s going to be okay? And finally #5 resolves the chapter.

I’m writing this post to the perspective of a Big Idea book, though your Idea can be weighted more toward narration, how-to, or academia. And I believe you can do this with a narrative story like a memoir or an academic white paper. You’ll just need to do some minor translation, mostly around the quadrants (a memoir might not show a how-to, but it will show what-you-did, which is in that same realm).

And here’s the big kicker: we’re not going to tackle them in that order.

We’re going to use the same format that got my rushed client through a solid chapter outline, and since we can’t use his material as examples, I’ll line it up against Dale Carnegie’s How to Win Friends and Influence People introduction.

We’re hijacking your brain here, so keep your paper close by and stick with me until you’re ready for a timer. Ready? Here goes.

Minute 1: What’s the Key Takeaway?

I started my client’s chapter outline with this question, because it tends to be most present in our minds. Every chapter is a gift to the reader, and we often know the what far better than the how. Other ways of phrasing this question might be:

- What lesson did I learn about this topic?

- What was the pivotal moment where this became real to me?

- How did I grow in this phase of my life?

- What can the reader hang onto after they turn the page to end the chapter?

- What do I want them to be able to do differently because of this chapter?

- If I’m successful in this chapter, what will that look like for me or the reader or both?

Write the whole time the timer is running, or talk it through with a friend or editor. When you’re done, you’ll find that this is procedural quadrant material—the tangible, how-to flavored, real world stuff that can be seen and felt and practiced. It’s likely also the answer to a want or need that you or your reader have—the recipe, the policy recommendation, the relatable life lesson.

Scanning what you wrote, quickly look for connections and what stands out as the true key. Write it down against #3 on your list, phrased as a question aligned to the most basic of all crisis questions: What do I do now?

In the introduction of a book, the key takeaway is to keep reading the book. You’re making the case for the reader to keep flipping pages, and that’s done brilliantly in to How to Win Friends. “The rules we have set down here are not mere theories or guesswork. They work like magic.”

You want something as satisfying as a magic bullet, but you need something as reliable as rules. I’ve got both, so keep reading.

Minute 2: Why Do We Care?

Depending on the author-protagonist or reader-protagonist journey, you might phrase this question more specifically:

- Why does the reader want or need the key takeaway?

- Why did I set out to learn this?

- How did I bump into this life lesson?

The answers to this question reverse engineer the key takeaway to set up the inciting incident. What set us on this journey in the first place? What is the brain worm that will ultimately point us to that key takeaway?

This will go next to #1 in your notebook, as the inciting incident. This will also be phrased as a question, though you may be find some extra status quo statements built into it. I like this kind of structure: Because I/the reader struggles with X, we wonder…?

In the How to Win Friends intro, it’s depicted here: “They came to me because…the person who has technical knowledge plus the ability to express ideas, to assume leadership, and to arouse enthusiasm among people—that person is headed for higher earning power.”

Because smart people aren’t always as successful as they want to be, they wonder what other factors they might be missing. What are the true factors behind interpersonal influence?

Minute 3: What Makes Us Resist?

Resistance is everywhere—and in a nonfiction chapter or book, resistance is our antagonist. There’s something getting in the way of the journey from ignorance to wisdom. What is it?

Alternate phrasing:

- What is my reader going to struggle against here?

- What kept me from learning this lesson sooner?

- What did I have to overcome to understand this concept better?

Remember, you’re taking your reader on a journey, no matter who the protagonist is. They’re living it, and that means they’ll live the resistance as well.

On the quadrant framework, this is the rest of the propositional content. In the commandments, it’s #2—the build up to the turning point “progressive complication.” You’ve already surfaced that they should care about the topic—now you’re making the case for it. You’re building toward the crisis moment where their walls of resistance have broken down so much that they can’t help but ask, “Okay, so if that’s true, what do I even DO about it?”

For my author, it was a clear delineation of the problem the book had intended to solve, so that the right reader would relate to that problem and want the solution. In How to Win Friends, it was the journey that led to the book: “This book…grew as a child grows. It grew and developed After fifteen years of experiment and research, came this book…” until culminating in the promise: “I have seen the application of these principles literally revolutionize the lives of many people.”

I’m not selling you an empty magic pill, and I’m not making stuff up. This isn’t something that will embarrass you. It’ll work.

Minute 4: What Makes Us Believe?

This is my favorite part of any chapter. It’s where we plug into mirror neurons, making sure the reader lives out our proposed shift as thoroughly as possible. It’s what makes integration possible. But I’m getting ahead of us here. Ask:

- What makes us believe this change is possible?

- What does my reader need to see to fully believe they can enact the key takeaway?

- How did I live out this change/concept?

- Who or what embodied the lesson for me?

This is where we get perspectival, on the quadrant map. We need this one. As readers, as writers, as we tap into our own journeys and map out new ones. Humans need to see other humans showing us change is safe.

That can look like stories. It can look like a deeper, more personal look at previous research. It can look like anecdotal integration of the how-to. It can look like a vulnerable recounting of the ways you struggled to embrace this knowledge and how you overcame it.

If you’re noticing a running thread of empathy here, you’re not wrong. Every bit of a nonfiction chapter should be infused with empathy for the reader’s experience. They have an inclination toward your inciting question? Good. Show them you understand not only that they are asking it, but why. Show them it’s just as real and valid as they thought and more—so much that they need to Do Something about it. And here, you’ll show them you understand it’s not easy to embrace, but that it’s possible to do so. That they can do hard things.

This is #4, and it’s the climax of the whole chapter. It’s make or break here—was the chapter even worth reading if the key concept is too far removed to ever integrate? Will you be able to move into a satisfactory resolution, or is more on the way?

In How to Win Friends, Carnegie spends a fair amount of time here. Some chapters will do that. He starts with “To illustrate…” and continues across several pages (in my copy) of various kinds of examples. Countless students…one man who couldn’t sleep…someone who wrote to him as he was writing…He covers an example for multiple forms resistance and various types of reader. Again, he’s making the case for the whole book here, and he does it brilliantly.

Whoever you are, however difficult this may be, you are not alone. You can do this. We’ve all got your back.

Minute 5: What’s the Big Invitation?

It’s time to shape the new world now—this is your moment to invite them into a new space now that the key takeaway has been theoretically realized.

One question really sums it all up:

- What can life look like on the other side of this chapter?

This of course is the resolution, at #5, and it’s participatory in nature. There is a sense of integration, of complex order that understands the world at large is difficult but a new world is possible. Because of that complexity, it’s likely also the inciting incident to the next chapter—or, if it’s the end of the book, the next chapter of their lives.

For my client, this was where he could reshape the reader’s perspective of his niche entirely, inciting a more aligned working relationship with the clients who will read this book. He’ll be able to begin with them on a different level than a non-reader, because the will have undergone the journey of the book and accepted the participatory invitation to his concept.

For the introduction of How to Win Friends, he almost dials back on the promises of magic and miracles to give a realistic, palatable, reasonable invitation: “If by the time you have finished reading the first three chapters of this book—if you aren’t then a little better equipped to meet life’s situations, then I shall consider this book to be a total failure so far as you are concerned.”

I’m not asking you to commit to much here. Just give me a few more chapters of your time. I’ve done my best to make them worth it.

For this post, my invitation is similar: if you don’t have at least a rough outline after a five minute exercise, the time I spent here will be a failure. But you’ll only be out a little bit of time.

And thus, hopefully, incites your own 5-minute nonfiction chapter outline sprint.

Prep Checklist for Your 5-minute Nonfiction Chapter Outline

- What is my nonfiction genre? Am I writing a How-To, Narrative, or Academic book—or a Big Idea that weaves in elements of all three? The same story can be told against each of these genres in equally powerful ways—but the emphasis and structure will vary. Have an idea of where the weight of your content will land within these genres before you begin outlining.

- Do I have a fiction genre I am mapping against? Is this about society? Love? Sustenance and survival? War (say, of art)? If you’re not sure what kind of emotional strings to pull in your chapter, the values that drive those genres can point you in the right direction.

- Where is this chapter in the book? This is a 5-minute chapter outline that we’re doing here, so if you don’t have a complete book outline, back up to another post about writing a nonfiction book. If you do know, consider where this chapter is going to show up. Broadly, are you in analysis mode, are you formalizing the concept, or are you ready to mechanize? For my client, it was the climax of the book and required a number of key elements in order to drive his concept home. The process of outlining is the same, but the content will (naturally) be different.

- Who/what are my protagonists and antagonists, and where are they on their journey? Big Idea comes with an author-protagonist convention. Reader-as-protagonist is another journey to consider, as they face their own battles of resistance and vicariously experience your journey to new wisdom. Antagonists may be those forces of resistance, literal, abstract, metaphysical, or otherwise.

- What is my POV for this chapter? Every point of view decision shapes the presentation of the story. For nonfiction point of view, I tend to think of it as levels of intimacy with the reader or authority on the topic. How do you want to convey this part of the material? Is it one on one, one vulnerably to many, or one distant authority to many? Think about it like this (in terms I’m at least somewhat making up, but that convey the point):

- I am sitting down with you over coffee to tell you something important (first person close)

- I am disseminating vital instructions for you to follow (first person authoritative/prescriptive)

- This is something important for us to learn (third person omniscient)

- This is something important for you to do (second person authoritative/prescriptive)

If you’ve already got a book outline or some material on the page, you should be able to answer those questions quickly. If not, again, go back to some previous posts on nonfiction structure and get those bigger, global decisions made first.

Remember: this stuff lives in you. If you’re telling the authentic story that won’t leave you alone, some simple time constraints and a basic map will help you get that chapter outline and subsequent draft on the page. Even on a deadline. Even to Story Grid standards.

You’ve got this. In 5…4…3…2…