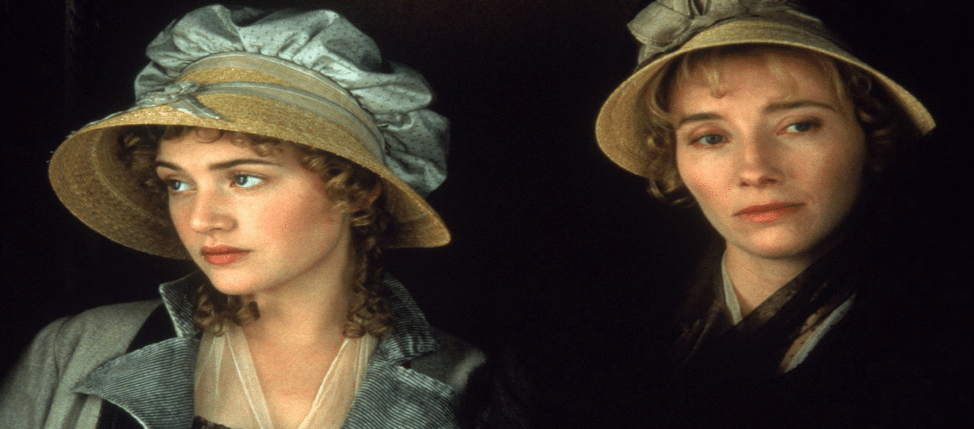

This week, Jarie pitched Sense and Sensibility as a great example of a Love Story. This 1995 film based on Jane Austen’s 1811 novel was directed by Ang Lee from the Oscar-winning screen adaptation by Emma Thompson. She is the first person hold Oscars in both acting and screenwriting.

And it marks our Ang Lee trifecta! Previously on the podcast we’ve analyzed two of his other movies: Crouching Tiger, Hidden Dragon and of course Brokeback Mountain.

The Story

Global Genre: External: Love > Courtship

Internal Genre: Elinor: Status > Admiration, Marianne: Worldview > Maturation

- Beginning Hook – When Elinor Dashwood’s father dies, leaving her and her sisters and mother in poverty, they must either continue as unwanted guests in their own home, or move far from friends–and from Edward Ferrars, the man Elinor has fallen in love with. They choose to move, and begin a new and restricted life in a small cottage.

- Middle Build – When Elinor learns that Edward is secretly engaged to Lucy Steele, she must keep that knowledge a secret despite her broken heart, and be thought unfeeling by her volatile sister, or else break her word. While Marianne falls obsessively in love with the handsome Willoughby, Elinor keeps the secret, taking solace in the understanding of Col Brandon, who is hopelessly in love with Marianne.

- Ending Payoff – When Col. Brandon has a parish for Edward, so that he can marry Lucy, he goes to Elinor. Elinor must decide whether or not tell Edward about the offer of a parish. She decides to tell him thus giving up hope of being with him since that’s the honorable thing to do. Lucy abandons Edward for Robert and Edward visits Elinor to declare his love for her.

The Principle – Jarie

Fans of the Story Grid know that Jane Austen’s Pride and Prejudice was the first Story Grid guide Shawn published and is one of the best Love Stories ever written. Jane Austen is the wizard of Love Story and since I’m looking at Love Stories this whole season, I decided to look at another one of Jane Austen’s stories about love — Sense and Sensibility.

If you recall from the teaser trailer, I’m looking at Love Stories so I can write a better memoir about a tough time in my life. I’m sure a lot of you listening have thought about writing a memoir or creative nonfiction story about your life experiences. Story Grid does also work for memoir and creative nonfiction, although we often don’t talk about it that much. We do have a couple of editors that just focus on creative nonfiction since the basics of story are the same.

What I have found on my own memoir writing journey is that in order for a memoir to work, it has to have a solid external genre spine that the writer’s Worldview can Maturate or Educate within or their Status can be admired upon. Without this spine, the life experiences lack focus and frankly interest. It’s for this reason that I’m convinced that writers of memoir or creative nonfiction need to read more fiction, especially love, performance, and status stories. Those seem to make the best spines in which to hang your life lessons on.

I should also note that on the main podcast, Anne and Shawn are digging into another great love story called Brokeback Mountain for their Masterwork Experiment. It’s already been an excellent discussion of the Love Genre. Anne, it’s almost like we planned it.

Anne: It is! Totally fortuitous, though.

You could hardly ask for higher contrast between two love stories: Brokeback Mountain is a late 20th century masterpiece of brevity coming in at under 11,000 words, and had to be padded considerably to make a full length feature film, but the screenwriters were able to use every scene, and almost all the dialogue exactly as written.

Sense and Sensibility, on the other hand, is an early 19th century novel of more than ten times that length at 120,000 words. It not only had to be cut considerably to fit the running time of a feature film, but had to be changed a lot to accommodate those cuts and to meet story expectations of modern audiences. I’ll have more to say about all this in a bit.

Jarie: Yeah. I could not get through the whole book because of they would go on and on about money and what it took to live. Emma Thompson did a way better job getting to the point. I also think that Pride and Prejudice is just a better story with more internal worldview shifts, which make it that much more impactful. Sense and Sensibility was her first novel, followed by Pride and Prejudice.

Let’s take a dive into why Sense and Sensibility is a great example of a Love Story. I already talked about the Beginning Hook, Middle Build, and Ending payoff so next I’ll look at the other questions in the editor 6 core questions.

#1 What is the Global Genre and the Value at Stake?

Global Genre: Love > Courtship

Value at Stake: Indifference to Commitment

Internal Genre: Elinor: Status > Admiration, Marianne: Worldview > Maturation

#2 What are the Obligatory Scenes and Conventions of the Global Genre?

Obligatory Scenes:

- Lovers meet

- Elinor meets Edward at Elinor’s home.

- Col. Brandon meets Marianne when she is playing the piano

- Marianne meets Willoughby after she falls during a rainstorm.

- First Kiss or Intimate Connection

- Edward goes to see Elinor in the stable.

- Willoughby touches Marianne’s ankle.

- Confession of love — We’ll listen to some examples.

- Willoughby tells the Dashwood’s that there is one thing in Barton Park that has his affections and that Marianne should not change.

- Col. Brandon calls on the Dashwoods in London asking about Marianne and Willoughby. He wishes them well as it breaks his heart to give up.

- Marianne blurts out that she loved Willoughby after receiving his letter and returning her lock of hair.

- Marianne goes to the knoll to look at Willoughby’s home and says a sonnet about love.

- Edward confesses to Elinor that he is not married and loves her.

- Lovers break up

- Willoughby is dispatched to London immediately, upsetting Marianne.

- Willoughby sees Marianne at the ball and rebuffs her, which breaks her heart again.

- Edward leaves for London without telling Elinor how he feels.

- Proof of love (Core Event)

- Edward comes to visit Elina after his brother marries Lucy.

- Edward tells Elina that his friendship with her is the best of his life.

- Elinor conveys Col. Brandon’s offer to Edward.

- Col. Brandon finds Marianne in the rain and carries her back home.

- Col. Brandon demands that they give him a job to help Marianne.

- Edward comes to visit Elina after his brother marries Lucy.

- Lovers reunite

- Willoughby and Marianne at the ball in London

- Edward visits Elinor and Lucy at Mrs. Jennings house in London.

Conventions for: Love Story > Courtship

- Triangle

- Elinor <-> Edward <-> Lucy

- Col. Brandon <-> Marianne <-> Willoughby

- Helpers/Harmers

- Mrs. Jennings, Sir John, Fanny

- Gender Divide

- Inheritance of Mr. Dashwood estate goes to his son.

- The precarious nature of “manless” women.

- Social etiquette related to women waiting for men to “ask them to dance.”

- Not having a dowry

- External Need

- Family security for the Dashwoods

- Opposing Forces

- Social status

- Love for love and not money

- Secrets

- Lucy is engaged to Edward.

- Elinor fell in love with Edward.

- The reason Willoughby went to London

- Col. Brandon’s secret that he has a charge, Beth, who disappeared and is with child. Willoughby knocked her up!

- Willoughby was going to propose to Marianne the day he left. So he had honorable intent.

- Rituals

- Picnics, dinner parties, invites from estates

- Elders making matches

- Bowing to each other and calling each other by formal names.

- Accepting one’s duty ahead of one’s happiness.

- Edward and Elinor’s walks in the country.

- Moral Weight

- Marrying for love, instead of for status, can ruin a person’s life.

Anne: Jarie, I think you’ve landed on a key cultural difference between the period of the story and today: women had virtually no choice other than marriage–and marriage with someone who could support them and their children–if they didn’t want to starve. It’s not that marrying for love rather than status can ruin your life; it’s that NOT marrying for status can literally kill you.

The moral weight, I would say, is suggested by what happened to Colonel Brandon’s young love, who wound up essentially a prostitute dying of consumption, and her daughter, who met a similar fate. The entire socioeconomic system insured that women could not win if they didn’t contract a respectable marriage. It was still a business transaction. Men’s role in an unattached woman’s descent into prostitution goes entirely unpunished. Even Willoughby, the scoundrel, ends up marrying a rich beauty. The only consequence for his immoral behavior towards every woman he’s met is a few tears while he looks down on Marianne’s wedding from the top of the hill.

Now that is moral weight.

Jarie: Indeed. You do have to have that context of the times.

#3 What is the Point of View/Narrative Device?

3rd Person Omnipresent + Free indirect style

#4 What are the Objects of Desire (Wants/Needs)?

Wants: To be provided for and protected

Needs: To be loved for who they are and not what they have.

#5 What is the Controlling Idea/Theme?

Love is a complex equation of sensible needs and sensibility of desires so that when two people meet, they have the best chance at happiness.

Kim: I’d put it differently, to cover more of the internal and external genre story spine–and to follow the Story Grid template:

“Love triumphs when lovers remain true to their selfless moral code and express affection as it aligns with honoring their duty and commitments.”

Anne: That’s great! How about a slight tweak to bring in the underlying sense-vs-sensibility theme?

“Love triumphs when lovers remain true to their selfless moral code and express affection in accordance with their nature, while honoring their duty and commitments.”

#6 What is the Beginning Hook, Middle Build, Ending Payoff?

See above.

Valerie: The E6CQ are invaluable! Personally, I think Sense and Sensibility pales in comparison to Pride and Prejudice (and although I love the actors in this film, the film itself always left me wanting), but until studying it for this episode I’d never given any thought as to why. Elinor and Edward don’t have internal shifts – in fact, Elinor is as passive a heroine as a story could possibly have! Although she appears reserved publicly, she’s suffering inner turmoil but we don’t really get to see that. Brandon’s Proof of Love is meh (he rescues her in the rain and rides off to get her mother) – in fact, Marianne seems like little more to him than a replacement for the woman he loved and lost. Marianne meanwhile, never really seems to fall in love with him at all. She simply accepts that he’s a very eligible match and won’t hurt her the way Willoughby did.

Anne: Elinor’s apparent non-change is what suggests a Status Admiration arc to me. I think Kim’s got that topic on her radar for today.

As to the Proof of Love: Shawn and I discussed this tricky subject a bit on the Masterwork Experiment, looking at the Proof of Love scene in Brokeback Mountain, and I’ve been struck by a change in his definition of the term.

Back when we analyzed the film Brokeback Mountain here on the Roundtable, we tentatively concluded that there was no Proof of Love scene. Leslie felt that Jack hanging onto the intertwined shirts all those years, and Ennis taking them home with him after Jack has been killed, didn’t come up to the Mr Darcy level of grand personal sacrifice–and it was hard to disagree with that.

Listen to the episode for a clip of my discussion with Shawn from episode 168 of the Story Grid Podcast, which I think might help clarify what constitutes Proof of Love in a love story.

I think we might say that Mr Darcy had a lot of status, money, and class to spare, so his sacrifice of those things had to be big. Ennis in Brokeback has almost nothing in this life to spare, so his Proof of Love is necessarily smaller.

In the case of Sense and Sensibility, Colonel Brandon proves his love through taking the only actions available to him–carrying Marianne across the estate in the rain (and Marianne is NOT a tiny wisp of a girl!), and riding off to fetch her mother to her–even though he has no real hope of winning her love.

I think Edward’s Proof of Love is a little harder to find, but–as I said in that clip and as Shawn agreed–you feel it. He confesses his mistakes and offers his heart, without any way of knowing whether Elinor returns his feelings. He basically says, even though I thought your feelings for me were only friendship, I came here with no expectations, but only to tell you that my heart is yours. That’s a fair Proof of Love for a guy who is as shy, self-effacing, and uncertain as Edward Ferrars.

Valerie: It’s not the scale of the Proof Of Love that I’m thinking about, it’s the intent behind it. The Proof of Love scene, after all, has to provide proof that one character loves another. Does Col. Brandon love Marianne? If so, why? What has she done to make him fall in love with her? He’s smitten, yes, but in love? It seems that she’s a replacement for the women he loved and lost. Marianne doesn’t fall in love, but she does come to appreciate Brandon. Edward shows up at the end, but that isn’t Proof of Love in my opinion. It’s proof of interest, yes. But love? Elinor comes the closest I think because she keeps his secret – and of course, I believe that the Elinor/Edward love story is far more developed in the novel and as such, is more satisfying to me. (My bias for the written word is showing!)

So then, while Sense and Sensibility is a great love story, I’m wondering what changes would have to be made for a contemporary love story. Is a historical love story different from a contemporary love story?

Anne: This IS an excellent question, and, I think, leads us to consider the archetypal nature of the key scenes. If we don’t live in a culture of honor where ratting out someone’s secret is a cardinal offense, what kind of restrictions would we have to place on a modern Elinor that would keep her Admirable to a contemporary reader?

What would constitute an internal moral compass for that Elinor? What would challenge that moral compass?

Possibly this story can’t be recreated. Only enjoyed as a historical artifact. I don’t know.

Valerie: I’m curious, Jarie – Did you have any a-ha moments when you were doing the E6CQ?

Jarie: I did and it was along the same lines of thinking as you. The typically internal shift for love story is Worldview > Maturation and it’s so thin in this story that you wonder what is going on in everyone’s head except for Marianne. Her worldview does shift but you don’t know why other than the implied “oh well, I guess I’ll take Capt. Brandon because he is available and won’t hurt me” like you said. I did find that the theme and confession of love scenes are great.

Kim: It’s so interesting because I feel completely the opposite! I see Elinor not as passive but as steadfast and selfless.

Anne: Me too! Thank you, Kim! She’s a hero to me.

Kim: Agreed, Anne. And to me Marianne has a strong Worldview-Maturation arc that shifts from a naive idealism about true love/passion to a more balanced view, one that recognizes that love is in no less strong or it’s impact at all diminished just because it’s less charismatic. Since she’s not our main protagonist, we don’t get to experience this maturation as closely as we do with Elizabeth Bennett (whose black and white view is certainly different), but as someone who has gone through a similar arc to Marianne in my youth, I understand her specific brand of naivete. It would be nice to have a scene where she expresses these new sophisticated views to Elinor, so that would be my editorial comment. We want to feel the change and, for as heart on her sleeve as she’s been, it seems natural that she would share this with Elinor. But there are a few moments that stand out to me that help demonstrate her arc of maturation that I’ll point out later. But just in terms of characterization, I love the stark contrast between Elinor and Marianne’s dispositions. Elinor seems to be locked away inside herself, which makes her misunderstood by others, and personally I find these kinds of characters absolutely fascinating and have found myself crafting them into my own stories.

Jarie: For this movie, I’m going to focus on three scenes/beats that I feel are a master class in storytelling. The first is the theme of the movie:

0:18:55 – 0:19:40 — What love is from a Sense and Sensibility (emotional) point of view.

This exchange between Marianne and her mother does a wonderful job explaining that Sense is Elinor and Sensibility is Marianne. You see this throughout the whole movie and both actors play each part perfectly. For those of you, like me, who are intellectual knuckle draggers, I had to look up sensibility to see how it contrasted with sense. The definition that most matches Marianne is quickness and acuteness of apprehension or feeling.

Anne: I think the meaning of “sensibility” has morphed into what we would today call “sensitivity.”

I see this scene as a brilliant compression of about ten miles of straight-up exposition in the novel. It performs at least four functions: 1) it demonstrates Marianne’s naive ideas as compared to Elinor’s greater emotional stability; 2) it foreshadows Marianne’s obsession love story with Willoughby by mentioning Juliet and Heloise; 3) shows the warm and indulgent relationship between Mrs Dashwood and her middle daughter–that indulgence contributes materially to Marianne’s excessive sensibility– AND 4) it cements the suitability of the match between Edward and Elinor, so that we’re rooting for it.

All that in less than probably a single script page.

Jarie: It is a brilliant and powerful. The next scene is a confession of love scene where Col. Brandon, confesses his love for Marinanne even though he knows he can never be with her.

1:13:46 – 1:15:06 — Confession of Love scene: Col. Brandon about Marianne.

This beautifully written and excellently acted. The pain in Col. Brandon face as well as his delivery is masterful. For us writers, this is a great example of pace and pause as well as his holding back of emotion that in his authentic character voice. Col. Brandon is set up to be a serious man with a secret that makes him reserved and cautious. While this speech would not be out of character for him, the words he uses and how he says that he hopes that “Willoughby will earn her love” or something like that, is a great way to state his love for her. His pauses are in character and show the internal struggle he has to keep it together. This creates tension in the scene since you don’t know if he’ll just blurt something out (not in character for him) or stay the course. The crisis question for Col. Brandon is “do I say what I really think?” He ends up halfway saying it without losing his cool.

In my opinion, the best confession of love scene in the world, or at least top ten, is when Edward visits Elinor and lays it all out on the line.

2:09:20 – 2:11:20 — Confession of love. Edward to Elinor.

Edward’s dialogue is delivered perfectly and Elinor’s reaction is both shocking and endearing. She finally loses her sense for a brief moment of sensibility. Priceless and right on theme. Again, the actor selection is perfect since Hugh Grant is the perfect meek suitor struggling to show his emotions.

Leslie: The biggest lesson I take from this scene is the way it’s earned by the events that come before it. Elinor rarely comes close to abandoning her stoic demeanor, even though she experiences deeply stressful circumstances—all because she’s committed to doing what she believes is right. Here are a few examples:

- When Lucy Steele confides that she’s engaged to Edward, Elinor promises not to tell, even though revealing the fact could get her out of what promises to be a painful trip to London.

- While the news is still fresh, and Marianne asks Elinor about that conversation, she claims it was “nothing of significance,” even though telling her sister about her troubles could relieve some of her distress and might avoid some awkward moments to come.

- When Edward arrives while Lucy is sitting in the parlor, Elinor gives nothing away, and alerts him to Lucy’s presence before he can say something he might regret. And when Marianne scolds her for her coldness toward Edward, she takes it without complaint.

- Even when she delivers news to Edward of Brandon’s offer of a job that would allow him to marry Lucy (and, therefore, keep his word), she praises him for honoring his promises and wishes them happiness.

With this setup, the moment when Elinor openly expresses her emotions is so satisfying because the storyteller has shown us many examples when she suppresses her true feelings in painful situations—for the good of others and when it goes against her own interests to do so—because these actions are aligned with her moral code.

Jarie: Yes. That is the only time in this whole movie where I like Elinor more than Marianne as a character. The fact that Elinor breaks down and then has cries of joy is a great way to show that Elinor is not just a robot.

Anne: I’ve got to take exception to describing Elinor as a robot! It might be slightly clearer in the book than in the film how much she’s suffering, because of course Jane Austen could simply tell us. And she does. At length. In introducing the Dashwood ladies in chapter 1, just after Mr Dashwood has died, she says of Elinor:

She had an excellent heart;–her disposition was affectionate, and her feelings were strong; but she knew how to govern them: it was a knowledge which her mother had yet to learn; and which one of her sisters had resolved never to be taught.

The text goes on to describe the way Marianne and Mrs Dashwood lash each other into heights of grief–that “excess of sensibility” that will nearly be the death of Marianne before the story is over–and then says:

Elinor, too, was deeply afflicted; but still she could struggle, she could exert herself.

In the screenplay, Emma Thompson had tens of thousands of words of just this kind of omniscient, free indirect exposition to manage, and of course she counted on her own acting and that of the rest of a stellar cast to convey much of that restrained emotion.

But she also added perfectly-pitched, subtle moments of speech and action, not found in the novel, that help the viewer sympathize with her:

For instance Edward catches her crying in the doorway while Marianne insists on continuing to play sad and mournful music. He’s the only one who seems to understand that she’s in pain. He tells his awful sister so. None of that is exactly from the novel, and it doesn’t depend on minute facial expressions or the pushing in of the camera, or the swelling of music. Those little bits are the writer’s craft, and the movie is full of them.

But in the end, Elinor is a Status Admiration character, and whether any individual reader or viewer finds her admirable is going to depend entirely on what they personally find admirable.

It might not be possible to appreciate this story–novel or movie–in any sense but that of looking back at a different culture and a different time, and accepting that it represents a social ideal two centuries gone.

However, I would call your attention to a song hit from about 120 years later, just to show that the proud, self-contained personality type is still around and still admired in at least some instances.

Jarie: Fair enough. Elinor is not a robot but I will say that my sensibility about her stoicism was making me want her to let loose and speak her mind. She deserves better than the situation she finds herself in. Just tell Edward you love him!

So how does this masterwork in Love Story apply to a writer that is trying to put their life experiences into a story?

Too often, writers get hung up on having to “tell the whole truth and nothing but the whole truth” when it comes to their life stories. Of course, we need to be as accurate as possible but we also have to make an engaging and compelling story that people will read.

I have no doubt that Sense and Sensibility is a synthesis of life in England in the 1800’s. Is it a little embellished? Sure but what you get out of studying something like Sense and Sensibility for your story is the fictional upper guardrail to which your real life should not cross. What do I mean by that?

When writers want to write a true story that works, the tradeoff is that most “true life” won’t work as a story. This “true life” is the lower guardrail or limit. The story that works is somewhere between the “true life” and the “fictional life” guardrails you have to operate in.

For example, the secret that Col. Brandon’s adopted child Beth was found pregnant in London with Willoughby’s baby would be hard to add to a true story. Now, if it was true, something like that would need some more setup to be believable. We give it a pass here because it’s fiction and Jane Austen.

So if you’re writing a memoir about a time in your life where your heart was broken or found true love, consider reading or watching The Bridges of Madison County, Pride and Prejudice, The Fault in our Stars, and The Princess Bride. Pay attention to how those obligatory scenes and conventions are done. Write them down and map your true life love story onto them. Create some guardrails to keep you honest and go write scenes that honor the truth but also entertain so your readers will keep turning the page.

Kim – Internal Genres and Core Emotion

The internal genre is broken so controlling idea / theme is broken so the viewers satisfaction is broken. Thrillers depend on internal genres to work.

I love this story, in fact I’m one of the rare few who enjoys it more than Pride & Prejudice. For one thing, the stakes are clearer. We really get to witness and experience the loss of status that befalls these women because they are unable to own or inherit property. The question of marrying for love or money is much more on the forefront, whereas in Pride & Prejudice it is certainly referred to but not witnessed. Rather here in Sense & Sensibility we see not only the the Dashwood women’s status drop, but Edward’s as well. So many lives dictated by fortune.

I think it is these more dire circumstances that seem to bring out more satisfying core emotions for me. Also, the fact that the entire family loves Edward and are all attached to him, so the loss of him is felt by more than just Elinor. Same goes with Willoughby. He was a friend to all of them, whereas in Pride & Prejudice her family is ridiculous and separate from every aspect of the courtship. I guess I just prefer the sweet family setting myself. There is nothing quite as satisfying as that final scene where Elinor sobs. It just destroys me every time. I love it so much.

Marianne – Worldview-Maturation

Beginning

- Character—fairly self-centered, not in a cruel way, simply because she is naive and her worldview is so narrow. Wants to express her deep feelings at all times despite how they affect others.

- Playing sorrowful tunes on piano after her father’s death

- She is mean to Fanny on purpose (although we definitely approve of this)

- Her flaunting behavior with Willoughby, ignoring Col Brandon

- Thought—very black and white view of what genuine Love is, what makes for a happy marriage, etc. Marianne believes all feelings should be transparently shown at all times and anything less written than that is because the feelings are not as strong.

- Her opinion of Edward (and his reading!), he’s too sedate

- Her opinion of Elinor’s lack of feeling, how she teases her about her “that I think very highly of him, I greatly esteem him, I like him”

- Timestamp 0:50:43 “If I had more shallow feelings perhaps I could conceal them as you do.”

- Her opinion of and behavior with Willoughby

- Her opinion of and behavior toward Col Brandon

- Status—begins by losing her father and being put out from their home. Faces misfortune, drops in status.

End

- Character—with her new awareness, she much more thoughtful of others and attentive.

- Her behavior toward Elinor, Col Brandon—acknowledges their feelings, kinder, less judgmental

- Thought—let’s go of her limited view of love, recognizes the deep feelings of others are expressed in many forms, and even when it’s less expressive than she herself would prefer. In fact she not only honors others expressions of love but seems to change her own definition of what she wants

- Status—marries Col Brandon, good fortune and status restored/increased

Notice that Marianne changes on all three of the internal elements, but it is the worldview change that causes the other two to take occur.

There are a couple moments that seem crucial to me in order to solidify Marianne’s maturation arc. The first is when Elinor sets her straight about the burden she’s been carrying in secret, this is before they leave London / before Marianne gets sick.

Anne: I feel that this is a significant turning point for Elinor, don’t you? We feel so gratified that she has finally spoken her mind!

Kim: Absolutely. So powerful. And the fact that she comforts Marianne afterward is further testament to her sense of duty/love for others.

And then when they are back home, after Marianne has recovered and befriended Col Brandon, her final closure moment re: Willoughby.

2:20:25 – 2:20:45 – Marianne expresses her maturity. “I compare it with yours”

Elinor is her mentor, and a large part of her maturation is changing her black and white view of Elinor (Friedman’s Worldview-Affective plot). Seeing that Elinor’s depth of feeling is no less than her own simply because it’s more subdued seems to directly correlate to her change in feeling for Brandon. She comes to recognize his depth of feeling, honor, and passion for life that he expresses in his own way.

Elinor – Status Admiration

Status-Admiration characters are the pinnacle of internal development–they’ve mastered Esteem, Self-Actualization, Self-Transcendence and now circle back to Esteem. They no longer need to change and it is this steadfast dedication to their moral code (like Maximus, Katniss, and Andy Dufresne) that causes them to gain esteem and rise in status.

Beginning

- Character—selfless, kind, thoughtful

- Thought—believes sense is Best and does not allow her emotions to interfere with her actions. Always acts with duty and honor.

- Status—begins by losing her father and being put out from their home. Faces misfortune, drops in status. Fanny keeps Edward away from her for this very reason.

End

- Character—does not change

- Thought—does not change

- Status—remains steadfast and selfless throughout, as does Edward. Though he loses his fortune, his honor gains him a parish from Col Brandon and frees him from his engagement which allows him to marry Elinor.

The Core Emotion is the emotion we go to feel–and there may be lots of other emotions evoked, but if you don’t create a situation in your story that allows the reader to experience this emotion the story will not be satisfying. See Anne & Leslie’s post on Discovering Your Story’s Core.

Love = Romance

In Sense & Sensibility, we get many sweet moments of conversation throughout Edwards first visit. Edward’s character is revealed through his action (doesn’t take the family room, helps with Margaret, sticks up for them to his sister, gives Elinor a handkerchief, invites her for a walk, humorous conversations with Elinor, tries to read as Marianne instructs him, shares his hopes for the future, helps her with her shawl, even his stutter through his confession about his proposal is endearing), all of this builds his character and our attachment to him. We see the whole family attach to him—mother, Margaret, even Marianne despite her criticism of his reading. As I said this makes the stakes that much more rewarding to me.

This sets up the longing and aching we experience throughout the rest of the film when Elinor and Edward are kept apart. This isn’t exactly romance but it is depth of feeling. I’m finding that perhaps I enjoy stories where the lovers feelings are genuine but other things are in the way of their union, rather than when lovers actually disliking each other and expressing animosity (like in Pride and Prejudice). This could certainly be a byproduct of my own harmonious disposition, and I can see it at play in my own novels. Admittedly I’m the kid who got too stressed out by Donald Duck cartoons because bad things always happened to Donald. Watch Mickey Mouse or Bugs Bunny—everything always works out for them.

Of course the scene when lovers reunite and Elinor sobs is just the best ever, but even in the final scene with the wedding procession leaving the church, there’s a small moment when Edward kisses Elinor’s hand and the look they share is just the sweetest thing. I find this ending more satisfying personally than Pride & Prejudice.

Status-Admiration = Respect and Admiration

There are also Core Emotions for Internal Genres. For Status-Admiration story, Norman Friedman describes the experience of the audience as: our long range hopes are fulfilled (similar to Sentimental) but our final result is respect and admiration for a person outdoing themselves and our expectations for what an ordinary person is capable of. This is precisely what we see for Elinor.

Valerie: Ok, I can see where you’re coming from here … but I’m still not convinced that Marianne and Brandon love one another, and I don’t think love and romance are the same thing – certainly not in contemporary society. In a historical setting, love and romance might well be the same thing…this brings me back to my earlier question.

This all raises the question about what is love? What is a demonstration of love? Articulating this is where the artistry comes in. This is what makes one love story different from another, and an area authors can innovate if they’re willing to think deeply about this.

Ok, Anne, we’ve already touched on the difference between writing for the page and the screen, but I’m curious to hear what else you have for us.

Anne – Novel to Movie

I’m studying novel-to-movie adaptations this season, in order to understand what distinguishes the two forms of storytelling. In Sense and Sensibility there is such an embarrassment of riches to discuss on the subject that I can barely scratch the surface.

I read Sense and Sensibility fairly early in life–maybe in my 20s–and when I saw the movie a couple of decades later, I thought it was a perfect adaptation. It was so true to the novel! I loved it. I bought it on DVD. I’ve watched it any number of times.

Then I re-read the novel last year. I was amazed at how very little of it is in the movie. Emma Thompson has eliminated or combined many characters, elevated some minor characters to major, altered the timeline, created wholly new dialogue in the most important scenes, added bits of comedy…it’s remarkable how much she changed.

This is usually a recipe for lovers of the novel to hate the movie.

But you know what? The film is still incredibly true to the book, and I still think it’s a perfect adaptation. So, apparently, did the Academy Awards.

Why is that?

I see two main reasons: First of all, Emma Thompson understood the novel, the period in which it was written, its author, and all its nuances, and didn’t add anything to the screenplay that isn’t to be found in some form–usually in the subtext–in the novel.

For instance, the novel contains a lot of Jane Austen’s wry, dry humor in observing people, but it’s SO dry and depends SO heavily on the reader’s familiarity with the times, that Thompson was smart to amp it up a little.

For example: the dinner scene with Sir John Middleton and the vulgar but likable Mrs Jennings, for instance, is nowhere in the novel, but both characters are pure Georgian England types. The jokes they tell, the discomfort they cause, the mix of kindness and bad taste they project–are pitch perfect for the period, The scene is a distillation of pages of comments Jane Austen makes about both characters, but it’s in a more accessible form: it makes us both laugh and cringe because who hasn’t been embarrassed by prying questions at the dinner table from uncensored elders a time or two?

Ditto Margaret’s treehouse and practice fencing with Edward, and the atlas–all created by Emma Thompson, not by Jane Austen. They fit the times well, and what’s more, the film needed a bit of a Herald character to do the job of–again–some of the masses of exposition in the novel. Margaret, who barely registers in the novel at all–her name occurs 33 times in 120,000 words–was a good choice to play another uncensored voice, who will say what others are thinking.

Thompson’s take on the characters makes them as relatable as possible to modern audiences without modernizing them. She simplified the complex web of family relationships and inheritance laws that drive the Dashwood ladies away from their home–mostly by just minimizing them as far as she could. She never tries to water down the strict mores of the period and class, but if you think Jane Austen ever outright mentioned illegitimate children, or women winding up being “passed from man to man” (as Mrs Jennings says in the film), then you don’t know your Jane Austen. Austen was so oblique about social and sexual sins like those of Willoughby and even Colonel Brandon, that modern readers need a translator.

So Emma Thompson translated–while still maintaining the sense that these things just aren’t talked about in the polite society of the story.

She lifted only a handful of the very best, most memorable lines of dialogue out of Jane Austen’s long, long speeches, and then wrote huge amounts of fresh dialogue, with a perfect ear for Austen’s style–while simplifying the syntax just a bit for the modern ear. This period is my specialty, and I can tell you that there’s not a line in the movie that rings false.

Kim: I think this is another reason why I love this story so much, the dialogue and humor are absolutely my favorite. Edward’s charming conversations with Elinor and Margaret are just the best. And Elinor too has so many great lines to her family. I can see this approach to timing has greatly influenced my own approach to dialogue and I’d recommend anyone looking to write humorous dialogue to check this out. The understatedness is just perfection.

Anne: Isn’t it great?

The second thing that makes the adaptation so perfect is that it was never intended as a Hollywood movie. A Taiwanese director, a British screenwriter, an all-British cast, all English locations–there is nothing Hollywood about this adaptation. Unlike, for instance, the adaptation of A Little Princess that we analyzed in our first episode this season, here there was no pressure to dumb down the story, change the protagonist’s internal genre, or add unnecessary action sequences. What’s more, the only sexing-up they did involved making Mr Ferrars as attractive as Hugh Grant. They did not have two lovers meeting outdoors in their nightgowns! (I’m looking at you, 2005 Pride and Prejudice starring Keira Knightley…)

So not only is this screenplay a great adaptation of a great novel, but if you study it side by side with the novel, it’s a graduate level course in nuanced, condensed, rich and clever storytelling whether you’re writing a novel OR a screenplay.

A final note: Emma Thompson spent four and a half years and 13 drafts working on this script. My hat is off to her forever!

Leslie – Core Events, Life Values, and My Own Cognitive Dissonance

I’m looking at Core Events and how they are related to Life Values, but I need to start with a correction from season 2. Mea culpa, Anne. Your explanation about the connection between the lover’s available means and the level of sacrifice makes sense to me. So today I would say that the Proof of Love is present in Brokeback Mountain, but it doesn’t necessarily result in a positive ending—or at least not a straightforward one.

Honestly, I’m still confused about whether Brokeback Mountain ends positively or negatively—and what I’m starting to think is that it’s more in the eye of the beholder than I imagined before. (I realize Brokeback Mountain isn’t today’s film, but I promise I’ll bring this back to Sense and Sensibility.)

In an Action Story, the result of the Core Event is usually aligned with the ending of the story, and I suspect the same is true most of the time for most of the external genres. But after hearing Shawn’s discussion in episode 168 of the Story Grid Podcast, it seems that Love Stories are a hybrid of internal and external that follow slightly different rules—at least on occasion.

The clip tells us what the Proof of Love is all about, but what is the definition of the positive life value Commitment that lovers want to reach in a Courtship Love Story? And does Proof of Love equal Commitment automatically?

After many hours of trying to get to the bottom of this, and going back and forth on the point, I don’t think the Proof of Love must be connected to, or result in, the positive life value of Commitment. This is how I worked this out.

Shawn has defined Commitment as “the monogamous binding of two people to form a third metaphysical being … the love between two,” in other words, a commitment “to fidelity and honesty and servitude to one above all others.”

But performing the Proof of Love doesn’t guarantee that the loved one will reciprocate—in fact that’s kind of the point, isn’t it? The lover makes a sacrifice with no guarantee that it will do them any good.

The Proof of Love demonstrates the authenticity of love, and authentic love is required to form a Commitment, but authentic love doesn’t always lead to Commitment and a straightforward positive ending to the story. But I also think the way we interpret that ending depends on what we bring to it.

Brokeback Mountain is an example of a Courtship Love Story that includes a Proof of Love, but doesn’t have a straightforward ending. Jack and Ennis couldn’t commit to each other openly without risking death. So they didn’t commit to “fidelity, honesty, and servitude to one above all others,” but they had a deep connection that was much more than what we see in an Obsession Love Story. So they achieved what they needed—connection and being known by another human in the context of romantic love—but were denied the benefits society usually bestows on lovers who are willing to commit: financial benefits, security, and status.

What about other situations when the Proof of Love is present but the lovers can’t or won’t commit? In The Bridges of Madison County, Robert risks his independence and asks Francesca to leave with him. In a sad twist, her Proof of Love is actually declining his offer because she knows that leaving her family would rob their love of its Moral Weight and ruin her relationship with Robert forever.

What if one lover doesn’t make a sacrifice, but is only the recipient of one, as is the case with Marianne in this adaptation of Sense and Sensibility? This could be an instance of a subplot where not all the obligatory scenes are dramatized—or maybe Marianne just got lucky. She gives up her naive Worldview, and that’s a loss to her, but she doesn’t sacrifice anything for Brandon. That said, what could be going on is that the Marianne-Brandon love story is secondary, and the obligatory scenes for subplots aren’t always dramatized.

I’m not sure I’m any closer to understanding this all right now, but I think it’s useful to engage in the inquiry even if the answer takes time to arise. You could call it authentic inquiry.

Listener Question

To wind up the episode, we take questions from our listeners. This week’s question comes to us from Monica T. Rodriguez, who tweeted to the main Story Grid podcast. Monica writes:

Great analysis in this week’s podcast! Listened to every episode, read the book, STILL learned something this morning. Question: You recommend the all is lost moment around the midpoint, but I’ve always seen it rec’d for near the end of Act 2. Is there wiggle room?

Anne: Great question, Monica. I thought the answer was pretty simple till I went hunting for what Shawn has said on the subject. It took Kim and Leslie joining the hunt to cobble together an answer. As with so many things in the Story Grid world, it’s a bit squishy.

Shawn says: You don’t necessarily have to be spot on the middle of your novel to have the all is lost moment. What you will discover, though, is that a lot of them are at the middle. Pride and Prejudice is at the middle, Silence of the Lambs is at the middle, and the all is lost moment is the moment when the character, the protagonist, recognizes that they can no longer bullshit themselves. They have to change. The all is lost moment is when we discover a lie that we’ve told ourselves and we recognize it for what it is, it’s a lie.

When I look through all the stories we’ve studied here on the Roundtable, I find that the majority of All Is Lost Moments we identified have been closer to the 75% mark–which is to say, closer to the global crisis and climax.

We’re all thinking about this now, and our current consensus is that we may be looking at TWO All Is Lost Moments: one for the internal genre and one for the external. Shawn identifies Elizabeth Bennet’s All Is Lost Moment as the point where she reads Mr Darcy’s letter–which is unsparing in its criticism of her family–and has to admit that he’s right and she’s wrong. Her worldview is suddenly and drastically changed. That’s her worldview All Is Lost Moment.

BUT from the perspective of the love story, which is the external genre of Pride and Prejudice, I think most readers and viewers would agree that her All Is Lost Moment is when she’s hoping for a proposal of marriage from him, and her stupid little sister creates a scandal that seems sure to drive Mr Darcy away in disgust. Her hope for love seems lost.

Notice that the internal All Is Lost Moment is what causes Elizabeth to change toward Mr Darcy–to soften her own prejudice and admit that he has some reason for his pride–so that she CAN begin to hope for marriage with him. If that hadn’t happened, then there would be nothing for her to lose when sister Lydia runs amok.

So maybe we could say that in a well-crafted story with both an internal and an external genre, the internal genre All Is Lost Moment, closer to the midpoint, both precedes and makes possible the external All Is Lost Moment, which is closer to the 75% mark.

There are more nuances to consider here. The type of story you’re telling may skew the story math a little and require a longer or shorter beginning hook, or a faster or more leisurely ending payoff. Consider this answer a working hypothesis. We’ll continue to think about it, and I hope you will too. Great question. Really got us thinking!

If you have a question about any story principle, you can ask it on Twitter @storygridRT, or better still, click here and leave a voice message.

Join us next time when Kim takes us through Jupiter Ascending as an example of a story that doesn’t work. Why not give it a look during the week, and follow along with us?

Your Roundtable Story Grid Editors are Jarie Bolander, Valerie Francis, Anne Hawley, Kim Kessler, and Leslie Watts.