This week, Anne pitched Love Actually for her ongoing study of complex story forms–in this case, the miniplot structure. This 2003 British film was written and directed by that champion of love stories, Richard Curtis, and despite its mediocre metascore of 55, it still figures on a lot of lists of favorite romantic movies and holiday classics.

The Story – Anne

Love Actually is nine stories … actually.

- Billy Mack and Joe, a “buddy love” story: When an aging rock star’s Christmas song surges up the charts, he must choose decide whether to spend Christmas in the shallow party life he used to know, or admit that his manager is really the love of his life. He spends Christmas with his manager–but goes on enjoying his career revival, too.

- Jamie and Aurélia, courtship. When a brokenhearted writer retreats to the South of France and meets a sympathetic woman who speaks no English, he must accept that the language barrier between them is insurmountable, or else do something about it. He goes home, learns Portuguese (sort of), and returns to marry her.

- Daniel, Sam, and Joanna, a fledgling courtship story with a brilliant proof of love moment: When a newly-motherless young boy falls for a girl at his school, he must convince his grieving stepfather that love is still real before the girl goes home to America, or else give her up. His stepfather joins the love campaign and together they contrive a way for Sam to let the girl know his feelings.

- Harry and Karen, a marriage love story. When a middle-aged wife discovers her husband’s infidelity with a beautiful young coworker, she must choose to express her hurt by making a scene, or else suppress her pain for the sake of their family. She tries to suppress her feelings, and the family survives, but the marriage is permanently marred.

- Colin and the American girls, status sentimental with a sex-farce style: When a goofy young Englishman has no success in love at home, he can either listen to his friend’s Herald-like warnings and accept his loser status, or ignore advice and go where he believes women will be more receptive to him. He goes to Wisconsin and finds wild sexual success with beautiful American girls.

- John and Judy, courtship. The simplest story of the nine. When two people meet on their very unusual job, they must overcome shyness and reserve to admit their attraction and become a couple. They do. That’s it.

- Juliet, Peter, and Mark, an obsession love story. When a newlywed bride learns that her husband’s best friend has been in love with her all along, she must either confront his feelings or hide. She hides, but he forces her to acknowledge him and goes away satisfied when she does, while she chooses to keep the secret from her husband. This is widely considered the creepiest and least satisfying of the nine stories.

- David and Natalie, courtship: When the new British Prime Minister falls for an employee at 10 Downing Street, who is subsequently sexually harassed by the President of the United States, he must choose whether to keep her around and be tempted into an indiscreet affair, or have her transferred. He has her transferred, but it’s no good: he seeks her out on Christmas Eve and declares his love.

- Sarah and Karl, which I experienced as a morality/testing/surrender story. When a lonely woman falls for a handsome coworker, she must choose to open her heart and life to him, or continue giving all her energy to her institutionalized brother, whom she can’t really help. With codependency masquerading as altruism, she sticks with her brother, depriving herself and the man of love.

Because each mini-story has its own little arc, the overall story is a little hard to track as a separate entity. But We Are Story Grid, and we don’t give up easily. I suggest that Love Actually boils down to something like this:

Beginning Hook: As an aging rock star’s comeback Christmas song hits the airwaves, an interconnected group of something like 27 characters all face love-related dilemmas.

Middle Build: As obstacles to love mount, the many characters face difficult choices about pursuing their heart’s desire. As Christmas arrives with its pressures and joys, some give up, some persist, and some cause pain to those already in their lives.

Ending Payoff: While some characters prove and confess their love and find happiness, some back away from love, others accept the imperfection in their relationships, and life goes on.

So, here’s my best shot at a controlling idea:

Love prevails when lovers are honest, risk vulnerability, take a chance, or follow their hearts, but it fails when lovers are unfaithful, uncommunicative, or unable to give of themselves.

Pretty straightforward, really.

The Principle

Anne – Leslie, you provided an outstanding rundown of the conventions of a miniplot story in our episode a couple of weeks ago on A Man Called Ove. Some of your observations apply here, and some don’t, but I’m identifying Love Actually as a miniplot for three reasons:

- Shawn says so.

- It’s made of nine different stories. They are mini. They have plot. Therefore, miniplot? But while they have a certain standalone quality, they are connected, taking place simultaneously, among a group of interconnected characters.

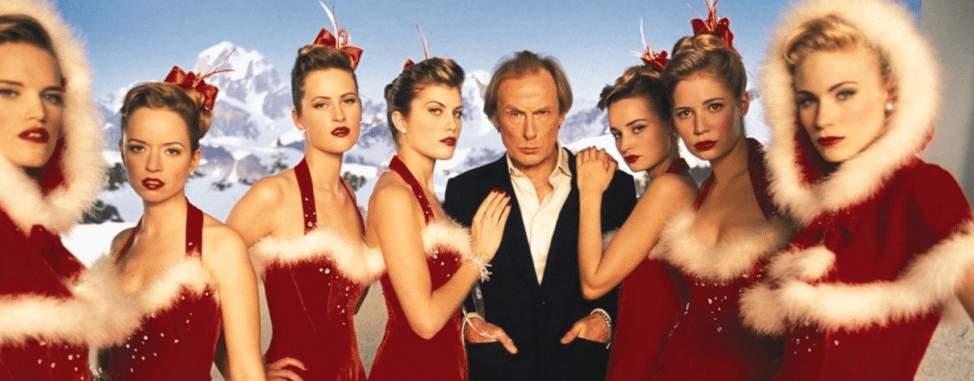

- If I squint, I can see Billy Mack, the aging rock star played by Bill Nighy, as a kind of central meta-protagonist, something like Santa Claus or a Trickster-Wizard archetype reigning over the world of the story, with a silly song and an easygoing spirit that binds the other stories together.

The miniplot structure is something I encounter in a certain type of literary novel. Two that I’ve read recently are The History of Love by Nicole Krauss, and Crooked Heart by Lissa Evans.

Novels like these are not plotless, as some readers seem to feel that literary novels are. They generally have internal plots and don’t turn on life and death stakes, but they have a curious narrative drive all their own, and I think it’s a subtle form of mystery.

The sense of mystery boils down to the question “What do these different story threads have to do with each other? How will they come together in the end? What’s the connection here?” There’s a puzzle quality that keeps fans of the form reading, because there’s real satisfaction in seeing the threads come together in the end.

Valerie – I agree with you, Anne. On the macro level these are exactly the questions that we’re wondering. They’re always there in the background and we’re waiting for them to be answered. However, each of the 9 stories raise their own questions which is why each of them is compelling; some more than others perhaps. Given that they’re all love stories in one form or another, the micro questions are specific to the situation but are all essentially about the lovers and whether they’ll get together or stay together.

Anne – Yes, and because they’re Love stories and therefore technically external genres, they have a bit more of a plotty feel than purely internal stories have. Humor and pathos make us sympathetic to various characters, and then big question of whether and how love will triumph is enough to keep each story’s momentum going.

So in this sense, Love Actually is different from the miniplot literary novels I’m familiar with.

But they do have in common that puzzle feeling. Each character is connected to one or more of the others by work, marriage, family, or friendship. Some genius on the internet made a chart showing all the connections. I love geniuses on the internet.

Little clues to the connections are sprinkled throughout the movie, so right away, as the story opens, there’s that sense of intrigue and puzzle-working: Oh, Emma Thompson is friends with Liam Neeson, we learn right away. Oh, look, Colin’s overly cautious friend is actually the director of photography at the porn studio where Martin Freeman works–we figure that out around the midpoint. Towards the end we discover that Karen–Emma Thompson’s character–is the sister of the Prime Minister, and that Mia and Natalie are next-door neighbors. These little pops of surprise sprinkled throughout help maintain engagement.

Do the connections among the characters drive any of the plots? Not that I can see. No one from one story has a strong impact on the other stories–unless you count Billy Mack’s cheerful, silly Christmas pop song amusing everyone. The connections seem to be there mostly to unify the stories under a single roof, so to speak.

But they do come together in the end. It’s implausible, but “One Month Later,” in a kind of epilogue, everyone’s at the airport, arriving or greeting someone. Billy Mack is met by his widely-grinning manager; Jamie and his new wife Aurelia arrive to be greeted by Juliet, Peter, and, in an unlikely turn of events, Juliet’s stalker Mark.

Alan Rickman’s Harry comes down the ramp to be met by Emma Thompson and their kids, and the lukewarm nature of the marriage becomes apparent in the way the greet each other. Little Sam’s singer girlfriend Joanna has returned to London…I mean, the entire cast is for some reason at Heathrow on the same day.

It’s wholly implausible, with a ridiculous disregard for airport security, but as the final couple–the Prime Minister and Natalie–meet at arrivals and fade into the documentary footage of real people at Heathrow, same as in the opening scene, it’s remarkably satisfying.

Can this be accomplished in a novel?

Well, probably not quite the same way, since so much of Love Actually depends on its sheer movie-ness, notably the A-list stars, their stellar acting, and the great music.

But here are seven important points about the movie’s structure that will translate to the written form. Novelists should notice that:

- The stories are intercut, so that we never have time to lose interest in one before switching to another.

- The characters are introduced using exposition as ammunition like crazy. In short bursts and a few lines of dialogue, we find out each one’s walk of life, some of their connections to the others, and a hint of their objects of desire. This movie is a masterlass in introducing a large cast of characters.

Be aware, though, that it’s notoriously difficult to introduce more than two or three characters at once in writing without the reader becoming confused and overwhelmed. The reader doesn’t have the advantage of connecting visually to famous actors. A clear and obvious diverse set of names, speaking styles, and characteristics is going to be absolutely crucial.

- The stories progress to their middle builds and ending payoffs more or less in step with each other, so our sense of an overarching story with a beginning, middle, and end remains intact.

- Humor and implausibility play large roles here. If you’re going to tell multiple interrelated stories, this kind of light touch is probably the best way to go.

- The stories are connected by a common thematic element stated up front–that love is all around us–and by a detectable overarching controlling idea that I talked about earlier. There’s also an external time element that adds drive: the countdown to Christmas.

- The weaving-together is not perfectly pat, symmetrical, and flawless. Some of the nine stories are serious, others are ridiculous, some have more weight than others, and not every single loose end is tied up. Just most of them.

- The in and the out in this story match beautifully, and we can all take a writing lesson from that.

Jarie – Set, Setting, and Dialogue

I love nothing more than a British romantic comedy with the likes of Hugh Grant, Colin Firth, Bill Nighy, Emma Thompson, Alan Rickman, and Keira Knightley. I mean, c’mon, what more could you want on a Sunday afternoon besides a spot of tea and a McVitie’s chocolate covered digestive biscuit as you watch Love Actually.

The setting is pretty simple — London, England. With that, you’re going to expect British people with their British ways and dry British humor. As for the mindsets of the characters, there are many but the one that is on top of mind of all of them is love. I mean, it’s called Love Actually for a reason. Thanks Anne for picking an easy one for me.

Of course, there are other mindsets or feelings that the characters have but there’s like over 27 to keep track of so I won’t dive into all of them. I will, however, look at one in particular since I just love him as an actor.

The brilliant thing about this movie, other than the cast, is the dialogue. Thanks again Anne for giving me an easy one this week, even though I still had to put on the subtitles.

It was actually hard to pick some good scenes to look at because this movie has a ton of great exchanges like this one between Billy Mack, played by Bill Nighy and a DJ talking about his remake of one of Billy Mack’s old hits. Bill Nighy is one of my favorite characters in this film as well as a brilliant actor that nails this type of character and dialogue perfectly.

Time 0:20:48

DJ: So, Billy, welcome back to the airwaves. New Christmas single, cover of Love is All Around.

BILLY: Except we’ve changed the word “love” to “Christmas.”

DJ: Yes, is that an important message to you, Bill?

BILLY: (SNORTS) Not really, Mike. Christmas is a time for people with someone they love in their lives.

DJ: And that’s not you?

BILLY: That’s not me, Michael. When I was young and successful, I was greedy and foolish, and now I’m left with no one, wrinkled and alone. (SNICKERS)

DJ: Wow. Thanks for that, Bill.

BILLY: For what?

DJ: Well, for actually giving a real answer to a question. It doesn’t often happen here at Radio Watford, I can tell you.

BILLY: Ask me anything you like, and I’ll tell you the truth.

DJ: Best Shag you ever had?

BILLY: Britney Spears

DJ: Wow

BILLY: No, only kidding! (SNORTS) She was rubbish.

DJ: Okay, here’s another one. How do you think the new record compares to your old, classic stuff?

BILLY: Come on, Mikey, you know as well as I do the record’s crap. (LAUGHING). But wouldn’t it be great if number one this Christmas wasn’t some smug teenager but an old ex-heroin addict searching for a comeback at any price?

Billy then goes on a rant about his horrible life and how the youth have it all and he’s stuck with his manager Joe (who is off in background rolling his eyes and shaking his head). Throw in a few f-bombs and you get the perfect sense of Billy Mack as a washed up rockstar that’s grasping for any shred of dignity he had before fame and fortune consumed him and spat him out.

Anne – I’d like to weigh in here to say that this clip is also part of that masterclass in character introduction I mentioned. We learn so much, so organically, about Billy Mack and his life and desires here. It doesn’t feel forced or explanatory. This is what McKee means by exposition as ammunition.

Jarie – If we look at McKee’s Five Tasks of Speech, it’s pretty obvious what Billy wants to accomplish with his witty, crude, and honest dialogue:

- Desire: Billy wants the audience (and the DJ) to feel sorry for him.

- The Sense of Antagonism: Youth and society

- Choice of Action: Speaks his truth about his past and the craziness of why he is alone.

- Action/Reaction: The DJ, knowing that Billy will tell the truth, starts asking more questions

- Expression: A raw, swear word filled diatribe about his life, with a call to action to make his crappy new song #1. That will show the young, snobby rockstars.

This scene and Billy’s dialogue builds on our previous introduction with Billy and how he is a washed up rockstar that in his own words, “old ex-heroin addict searching for a comeback at any price.” It’s actually a masterful way to use dialogue to expose Billy’s past without using a flashback scene. As a bit of trivia, this is not Bill Nighy’s first rock star roll or first time we have seen him. In 1998, he played a washed up Rock Star in Still Crazy (same exact character) and in 2007, he was in Hot Fuzz as Met Chief Inspector, which we looked at in Season 1. I guess when you nail washed up Rock Star or bumbling police inspector, you can get after it.

There are so many great characters and scenes in this film that it’s hard for me to pick the best ones. I will say that each of the nine stories could have been its own film yet it seems to work nicely since the characters are connected in some way (albeit not Billy and Joe to anyone except themselves).

Speaking of chocolate biscuits and tea, this quick exchange as part of the David and Natalie story, is a setup for clearly what’s to come:

Time 0:23:02

DAVID: Okay. What’s next?

STAFF: The President’s visit.

DAVID: Yes, yes. I fear this is going to be a difficult one to play. Alex?

ALEX: There is a very strong feeling in the party we mustn’t allow ourselves to be bullied from pillar to post like the last government.

ALL: Hear. Hear.

STAFF: This is our first really important test. Let’s take a stand.

DAVID: Right. Right. I understand that, but I have decided not to. Not this time. We will, of course, try to be clever. But let’s not forget that America is the most powerful country in the world. I’m not going to act like a petulant child. Right, who do you have to screw around here to get a cup of tea and a chocolate biscuit?

(ALL LAUGHING) Natalie then enters the room with the tea and biscuits.

DAVID: (LOOKING at NATALIE YEARNINGLY) Right.

I know it’s a bit on the nose but you see two things in this scene. First, the type of man David is. He’s really not prepared to be the Prime Minister. He literally just got voted in a couple of scenes ago and his attraction to Natalie is clearly going to be a problem. If we look at the Five Tasks of Speech, we see the overt desires with sub-text as well:

- Desire: David wants to show that he’s in control

- The Sense of Antagonism: His cabinet, America, and loneliness.

- Choice of Action: Take the safe course. Complain about not having tea and biscuits

- Action/Reaction: Moans and laughs

- Expression: Shock when Natalie comes in the room.

In this scene you see Hugh Grant’s perfectly capturing the dilemma he faces. Soon after this, he even dances, awkwardly in fact. Colin Firth also puts in a great awkward performance as well. There is just something magical about an awkward englishmen.

What also makes this movie entertaining and funny and feel good is getting the right actors to say the right words, which I admit, is hard to do in a novel. Yet if you could somehow capture the Colin-Firth-esque awkwardness or the Emma-Thompson-esque tone and tenor or even the Bill-Nighy-esque mumble or the Hugh-Grant-esque look of mischief/despair/I-can’t-believe-I-said-that, you would add a rich sense of what a character is like. If you have any, let me know. I’d love to figure out how to capture on the page what a great actor does on the stage or screen.

Anne – So would I, Jarie. It’s a subject of intense interest to me, and part of what I want to study next season.

Valerie – Narrative Drive

Ok, so … narrative drive in a miniplot!

We’ve already talked about the kinds of questions that the audience is wondering at the macro and micro level. And, generally speaking, Love Actually relies on suspense (we know what the characters know).

I’ve already gone on at length about what mystery, suspense and dramatic irony are and how they generate questions in the viewer’s mind. However, in the Murder on the Orient Express episode I also said that it’s impossible to separate narrative drive from other story principles. It’s inherently linked to point of view, progressive complications, escalating stakes, exposition as ammunition and pacing, to name a few.

So now that we have a handle on what the forms of narrative drive are and how they work, I think it’s time we start diving into how they work with other story principles. I can’t go into all 9 stories, so I’ve chosen the Billy Mack status story and Harry/Karen love story as examples.

Billy Mack: The obvious question we’re wondering here is, will Billy Mack make a comeback? This puts us squarely in suspense because Billy doesn’t know any more than we do … or does he?

Bill Nighy is brilliant as always, but even he can’t give a great performance with a poorly written script. So I want to focus on the material itself here, because even though this is a film, there are lots of takeaways for novelists.

I believe that the genius of this storyline, in terms of narrative drive, is Billy’s complete irreverence. This one trait ties narrative drive to character development and objects of desire.

Billy is a man with nothing to lose. He knows his song is awful, he knows the chance of him making a comeback is slim to none. His objects of desire are crystal clear; he wants to reclaim his status (fame, money and all that comes with it) but he needs an authentic relationship in his life.

Billy has been in the business a long time, so while he knows there isn’t much hope for his career, he also knows how to play the media and the public. Now, this isn’t overtly stated and it’s obvious that his manager, Joe, isn’t aware of any conscious plan to manipulate public opinion. It doesn’t seem that Billy is consciously aware of it either (which is what makes him lovable and makes everyone root for him).

We get glimpses of authenticity, like when he tells the DJ at Radio Watford that Christmas is for people with love in their lives, and that doesn’t include him. (This is only Billy’s second scene and he’s articulating his subconscious need!) These morsels of truth slip out of him so naturally—he’s not even aware he’s doing it (which is why it’s a subconscious need). But then, he consciously tries to recover from it and gets back “on message” which in story terms, is his active pursuit of his want.

How does this impact narrative drive? It makes us constantly question what’s going on with Billy. Is he playing us? Was that line about Christmas being for people with love in their lives, an intentional slip or not? Just how desperate is Billy for a comeback? Has he really decided to depart from the strategy his manager has set out? Or is it that he’s played this role of the rock star for so long, that even Billy doesn’t know who the true Billy is?

This storyline doesn’t have a lot of screen time compared to some of the others, but Billy Mack is such a complex character that we’re compelled to keep watching to see what will happen with him. On one level he’s a complete arse, but he’s also charming and entertaining. We’re rooting for him. The other characters are rooting for him. This desire to know how things will work out for Billy … that’s narrative drive. We want him to get both of his objects of desire.

I think Love Actually is such a satisfying film because each of the storylines is complete. Billy’s story isn’t long, but it’s still richly developed. It’s the hero’s journey and we can’t help but engage with it.

Harry and Karen: Harry and Karen’s marriage plot is a totally different story than Billy Mack’s (external love story v internal status story). We don’t have the richness of character here (in fact, Harry, Mia and Karen are all stereotypes) but it’s nonetheless compelling.

Because of the performances by the late, great Alan Rickman, and Emma Thompson, Harry and Karen avoid being merely two-dimensional characters. But again, let’s try to put the actors’ performances aside for a moment, because as novelists that’s outside our wheelhouse.

This story works because the stakes are so incredibly high. Their marriage, and all that goes with it, is on the line. Harry is risking trust, love, his children’s happiness, family life and so on. What’s on the table here is betrayal and that, as Dante tells us, is the 9th circle of hell.

We want to know if Harry is going to take up with Mia. If he does, will Karen find out? If she finds out, what will she do?

The forms of narrative drive shift as the story moves along. It starts with suspense; we don’t know if Harry is going to be unfaithful and neither does he. It moves to dramatic irony when Karen finds the necklace and that’s when things get really interesting. The tension goes into overdrive, the stakes are at their highest. There’s a hell of a lot on the line here!

Even if Harry hasn’t had sex with Mia yet, we know he intends to pursue the relationship. He has already betrayed his wife on an emotional level. A feeling of dread sinks into us and when Karen opens the Joni Mitchell CD, our hearts break along with hers.

It’s hard to despise Harry, but that honestly is due to Alan Rickman’s performance. When Karen finds the necklace, we’re hoping—praying!—it’s for her.

We might not hate him, but we do lose respect for him. It’s not that his marriage was unhappy (in fact, it seems very happy indeed), or that Karen is a horrible person (she’s actually a loving wife, mother, sister and friend), or even that he’s a horrible person (he does want Sarah to find love).

He’s simply a middle-aged fool and it’s hard to respect a fool.

In this story, each new piece of information answers a question we have, but it also gives rise to new questions. We saw this in the Sherlock Holmes pilot episode, A Study in Pink. That’s the story I analyzed in the Fundamental Fridays post I did on mystery.

Narrative drive doesn’t exist in a silo. It works with other story principles to propel the story along. Here I’ve looked at character development, objects of desire and escalating stakes. I’m going to dive deeper into the relationship between narrative drive and story principles in a couple of weeks when we study my last film pick of the season. But for now, I’ll leave it there and hand things over to Kim.

Kim – Internal Genres

One of my areas of study this season with Internal Genres is the big WHY. Why do we tell stories like this? Why does humanity need them?

I am convinced every genre exists for a distinct purpose, it provides something we inherently need to understand and be reminded of. Often. In an Arch plot story, there is typically one main plot that plays out with fairly clear cause and effect and maybe a few supporting subplots. The meaning/theme of a story like this is typically pretty straightforward and clear.

But with Mini plot, we have a chance to explore a story’s meaning/theme from a variety of angles. The multiple interwoven threads can create a richer and more deeply satisfying experience for the audience. But with so many different threads and genres in play, and all represented with fairly equal weight, how do we keep the story from being muddled, keep the reader/viewer from coming wondering what was that all about, exactly? Luckily we have a great example here with Love Actually and certainly a masterwork to study.

Richard Curtis is one of my favorite storytellers, and in season three we studied another one of his films About Time, where he delivers the theme in well-written voiceover at the end of the film. He uses the same device in Love Actually but this time it’s at beginning the film.

Prime Minister [voiceover]

Whenever I get gloomy about the state of the world, I think of the arrivals gate at Heathrow airport. General opinion is starting to make out that we live in a world of hatred and greed. But I don’t see that. Seems to me love is everywhere.

Often it’s not particularly dignified or newsworthy, but it’s always there. Fathers and sons, mothers and daughters, husbands and wives, boyfriends, girlfriends, old friends.

When the planes hit the twin towers, as far as I know, none of the phone calls from people on board were messages of hate or revenge, they were all messages of love. If you look for it, I’ve got a sneaky feeling you’ll find that love actually is all around.”

So let’s take a pause there for a moment and look at the story threads woven for us in Love Actually. Now Anne mentioned them at the opening and I think we align on almost all of them. There are approximately 15 arcs in this story, give or take depending on how you slice it. Some are more substantial in nature, but even the thin ones still give me a reason to choose the genres I did.

Six Status arc (all Sentimental, as far as I can tell)

- Sam, kid drummer = Status-Sentimental

- Jamie, the writer = Status-Sentimental

- Aurelia, his housekeeper = Status-Sentimental

- Natalie, assistant to the Prime Minister = Status-Sentimental

- Colin, the goofy sex maniac = Status-Sentimental

- John / Judy, the nude stand-ins = Status-Sentimental

Six Worldview arcs (Four Maturation, One Revelation, One Disillusionment)

- Rockstar Billy Mack = Worldview-Maturation

- Prime Minister David = Worldview-Maturation

- Widower Daniel = Worldview-Maturation

- Colin’s friend Tony = Worldview-Maturation

- Newlywed Juliet = Worldview-Revelation

- Housewife Karen = Worldview-Disillusionment

Two Morality arcs (both testing, one triumph, one surrender)

- Mark, secretly in love with Juliet = Morality-Testing-Triumph

- Harry, the unfaithful husband = Morality-Testing-Surrender

And one conundrum, at least for me.

- Sarah, caretaker to her brother = I see Status-Pathetic or Worldview-Education possibly? Anne sees Morality-Testing-Surrender. More on this in a moment.

I think the threads that end obviously positive are pretty clear as far as how they contribute the the overall, so let’s look at the ones that are less clear.

The Thread: Juliet, Peter, & Mark

As we’ve mentioned, Mark is best friends with Peter, who is marrying Juliet. Mark is always cold to Juliet, making her (and Peter) believe that Mark actually dislikes her. But he is actually secretly in love with her and avoids showing any kindness/affection/attraction for her as a form of self-preservation.

To me, Juliet’s arc is akin to a Worldview-Revelation arc. She is missing key factual information about herself–that Mark is in love with her. When she finally learns the truth, she can then decide how to apply that knowledge, by acting with wisdom or foolishness.

Mark’s arc appears to be a Morality-Testing plot, and I believe he triumphs over it. In the beginning, he is living a lie, one that he claims is self-preservation (which happens to be a life value on the morality spectrum). At first, he is found out by mistake when Juliet comes by to look at the wedding video, at which point he retreats. But in the end, he comes to the door and tells the truth (relatively), but has at least stopped withholding himself. He owns his truth and then embraces closure.

When Mark show up at her door seeking closure, Juliet acts with kindness and compassion. She chooses not to tell her husband (which may or may not be foolish depending on which story we’re in) but in this case her actions seem to portray that marriage and friendship are worth preserving above all else.

The Thread: Karen, Harry, & Mia

Both of these arcs seem fairly clear to me:

Husband to Karen Harry is In the opening, he actively encourages Sarah to tell Karl the truth, acting as a kind of mentor. Mia takes an unprofessional interest in him, acting as a sort of temptress, one that he entertains rather than shutting down. He loses his strength of will and/or his moral code, as represented by giving Mia the necklace and Karen the CD. Who is to say how far it would have went had he not been caught. Certainly he is apologetic and aware of how much of an idiot he’s been, and how much he’s hurt his wife, but that won’t undo the damage.

Karen begins the story giving widower Daniel harsh but wise advice about love and dating, she’s funny, seems wise in life and love. Her interactions with her husband and children are sincere, but not naive to the ways of the world. She notices the way Mia is being toward her husband at the party and warns him to “be careful there”. Later, she finds the necklace in Harry’s pocket and falsely believes it is for her. If think of this in terms of her worldview, it’s as though she went from blind/justified belief to doubt to justified belief…Then when she opens her present and it’s a CD, she realizes the necklace was for someone else. This is the moment of disillusionment. What was meaningful has lost all meaning.

She confronts her husband later that evening, saying [insert clip]:

What would you do if you were in my situation? Say your husband, bought a gold necklace, then come Christmas gave it to somebody else? What would you do? Would you stay, knowing life would always be a little bit worse? Or would you cut and run?

One month later, we see she has chosen to stay. She and kids pick up Harry from the airport. He asks, “How are you,” to which se says, “I’m fine. I’m fine.” But it seems the reason she is staying is for her children and not for herself and the marriage.

Remember, Disillusionment arcs will typically end with the protagonist continuing with their previous literal action but the significance / meaning it hold has changed. In this case, due to the actions of her husband, Karen herself has lost the feeling of significance in her marriage / life. Personally, I would love to write a sequel to her story thread, to help her find it again.

The Thread: Sarah, Karl, & Michael

So the internal arc for Sarah is my conundrum. It’s what one of those times that the noodle-y aspect of the internal genres is in full force.

Here’s how it breaks down in Friedman’s Framework:

Protagonist = Sarah

- Beginning

- Character (Strength of will, motives, behavior) – we don’t get a lot of set up here, but Sarah is portrayed as sympathetic when we learn she is secretly in love with Karl for over two years.

- Thought – Again, we don’t get a lot of information but we see her cringe when she has to answer her brother’s call. She seems to begrudge her brother and his dependency. Tells Karl, “It’s fine. It’s not fine, it’s just the way that it is.”

- Fortune – Sarah is on-call for her brother 24/7, tied to her phone at all times. It interrupts her work and she can’t make time for herself, let alone pursue a romantic relationship, despite being in love with Karl for over two years

- Ending

- Character – She is still sympathetic but we see her give up her will at the midpoint, when she is finally connecting with Karl and her brother calls and wants her to come visit him. In this case she does choose her brother’s dependency as a possible negation of the negation.

- Thought – We don’t get a clear moment that portrays a shift in her worldview but we do see a moment when she is sad about Karl and actually calls her brother to talk to him, so she gets support from him as well. In the resolution of her thread, we see her with her brother at the mental hospital exchanging Christmas presents, putting the too long scarf around him, and he hugs her.

- Fortune – Her attempt to form a relationship with Karl has failed, due to her brother’s dependency. She has no support, there is no one else to help her.

So this leads me to narrow down to three possible choices:

Status-Pathetic

When a sympathetic protagonist, who has weak character and is too unsophisticated to see the consequences of their actions, experiences misfortune without the guidance of an adequate mentor, they will fail to rise in social standing.

Worldview-Education

When a sympathetic protagonist, with a naive or cynical outlook, experiences an opportunity or challenge that enlightens them to a broader understanding, they find new meaning in their existing actions.

Morality-Testing-Surrender

When a protagonist of highly developed will and sophistication experiences an opportunity and ignores their inner moral code, they may be rewarded externally but will suffer internally.

So the thing that tips the scales for me is the big meta why of each one of these stories, the reason why they exist. And for me I think Status-Pathetic is really the one that comes out the strongest. When Leslie and I were studying internal genres, we learned that Status stories really come down to the presence of an adequate mentor. And in this case, this means adequate external circumstances that can help them change their ways, change their circumstances.

And for Sarah, she has no support. And she certainly seems sophisticated enough that she could get that external support, but emotionally she is so connected to the outcome of her brother that she can’t tear herself away without someone else encouraging her and helping her. This is where I see someone like Karl at the midpoint–he doesn’t offer support. He’s sympathetic and he says, “Hey, life’s complicated.” But he doesn’t stick with her through it either. He gives up, too.

And that to me is the ultimate downfall of Sarah’s situation–she doesn’t have external support or circumstances or people who are willing to go to bat for her. If we don’t have those things, then people who are in these kind of caregiving relationships are doomed to remain stuck in them, burn themselves out, and never really get a life for themselves.

So the big meta why of this thread seems like if you see people in the world that are caregivers taking care of loved ones and don’t have additional support to step in and be that support. Sarah can’t get herself out of this situation without other people stepping in to help her.

Ultimate Meta Theme

So taking all that in context with the opening voiceover, I think the ultimate meta controlling idea and theme here is: Love prevails when we believe it does, when we look for it and act on it, despite any other circumstances. Delivering the voice over at the beginning seems to indicate that the storyteller wants us to be paying attention and looking for love in not particularly dignified or newsworthy places. And this seems to tell me that each thread, even if it does not end resoundingly positive, still has something positive to teach us about love, actually.

Demonstrating Life Values

The other think I wanted to mention was that when a plot/character arc is only “on screen” some of the time, it’s important to make those moments count. You have to make those moments do their job which, in terms of creating a meaningful arc, is to clearly depict the relevant life value in play at that moment. This seems especially crucial in mini plot where threads may not be “on screen” as often as they would if it were a singular arch plot.

In terms of internal genres, this means in these specific moments, the reader must be clearly shown the protagonist’s character / morality (strength of will, motives, behavior), their thought / worldview (beliefs, perspectives, personal truths), and their fortune / status (external circumstances and external goals).

There are a number of devices you can use to portray the specific life value at any given time, for example you can use setting, character action, dialogue, internal thought, etc. Being too “on the nose” may come off as cheesy or cliche, but on the other hand, clarity is essential. You want to strike the right balance in how heavy-handed you are in transmitting these life values. Be sure that whatever devices you use and the way you execute them fit with the tone and style of your story. A comedy vs a drama vs a satire for example allows for very different modes and measures of delivery.

To find the right balance for your story, I recommend a heavy dose of permission to experiment with your own writing, along with a heavy dose of masterwork study. And just to be clear, studying a masterwork is not a magical process–it’s really just the intentional observation of a story that works, a story you are seeking to learn from. You apply the tools as best you can and see what you find. Don’t feel pressure that your study of a masterwork has to be a masterwork. It is an act of exploration in and of itself. Try to enjoy it 🙂

Leslie – Love Story Conventions

I’m studying conventions this season, and I’ve put together a table with the love story conventions for the relationships in Love Actually that Anne identified earlier in the episode. There’s nothing earth shaking in there (with the possible exception of my take on the gender divide convention), though it was a great exercise and a great reminder of how useful it is to compare multiple stories (even in miniplot form) when you want to study story structure and other principles. Click here to access the table. (Big thanks to my fellow Roundtablers who provided feedback and suggestions!) Please keep in mind it’s a work in progress. Your comments and questions are welcome.

Listener Question

To wind up the episode, we take questions from our listeners. This week’s question comes to us from Mike Silva. Mike asks (1) Should I start novel writing with my passion project, and polish that, or wait? (2) Would it be better to hone the craft with short story writing first?

Leslie – These are excellent questions for any writing to ask themselves. And in a way it depends what your goals are and how you work.

Writing a novel that you can be proud of requires a great deal of effort; you’re going to spend a lot of time with your characters and the events of the story—if you want to aim for one that is at the top of the genre. You have to have some way of maintaining momentum and interest, or it won’t get done. Choosing a story you feel passionate about is a great way to help you stay the course. But sometimes we are so close to our passion projects that it’s hard to be objective—it’s challenging to be objective with our writing anyway! That can get in the way of killing our darlings and hearing solid feedback to make the story better.

I know a writer who felt he didn’t have the skills to pull off his passion project, a sweeping, epic tale of a complex world. He didn’t want to compromise on the quality, so he wrote stories of a smaller scope within his story world to work his way up to the more challenging one.

Now, should you start with short stories first? This is a great strategy so long as you understand how novels and short stories are different. Consider the difference between the 16-foot Goddess of Liberty atop the Texas Capitol building 308-foot building and the 6-foot Venus de Milo in the Louvre. They look very different close up because they are meant to do different things.

Short stories are shorter, and you can master the form more quickly because you can repeat the process more quickly, but you will need to convert those skills to longform writing once you figure it out. Understand that, and short stories are a great way to learn story craft before tackling a bigger story.

If you have a question about any story principle, you can ask it on Twitter @storygridRT, or better still, by clicking here and leaving us a voice message.

Join us next time to find out whether Leslie can make the case that 2012’s The Hunger Games is a great example of Action Adventure Conventions. Why not give it a look during the week, and follow along with us?

Your Roundtable Story Grid Editors are Jarie Bolander, Valerie Francis, Anne Hawley, Kim Kessler, and Leslie Watts.