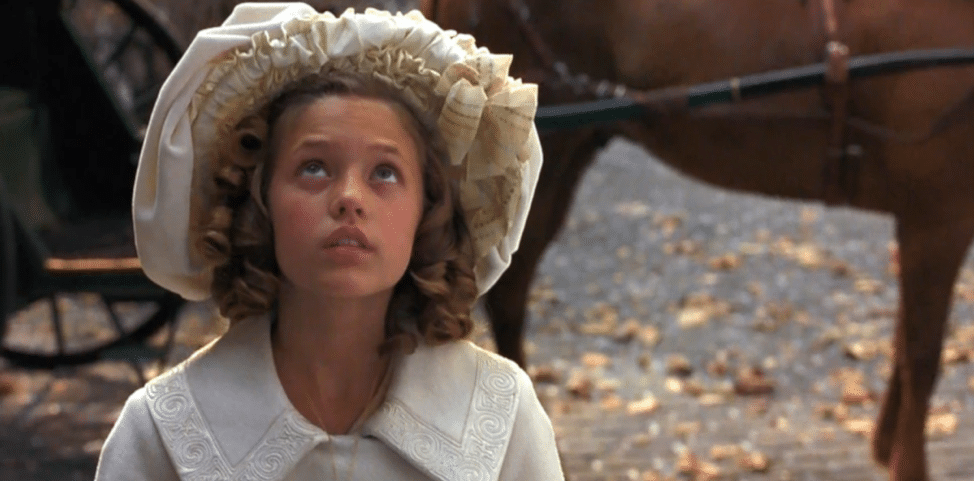

This week, Anne pitched A Little Princess in order to begin her Season Five task of studying the differences between novels and their adaptations to film.

A Little Princess is a novel by Frances Hodgson Burnett, originally published in 1905. The film we watched this week is the 1995 adaptation written by Richard La Gravenese and directed by Alfonso Cuaron. It was only Cuaron’s second film, and his first in English, for a Hollywood studio.

The Story

The novel A Little Princess is one of my favorites. It’s been in print since 1905, and has been adapted to multiple movies and stage plays. I’ve read it and listened to the excellent audiobook version many times. For all that it’s incredibly corny by 21st century standards, it’s still pleasing and satisfying to those in its target audience–generally girls and people who remember being girls. It’s part of a pretty venerable tradition of boarding-school stories–a tradition that has continued right up to Harry Potter.

So what’s it all about?

Genre: Novel: Status Admiration (Society secondary?) Movie: closer to Worldview

- Beginning Hook – When 7-year-old Sara Crewe is delivered to Miss Minchin’s boarding school, she must adapt to the restrictions of her new life or else risk disappointing her beloved father. She does her best to adapt–while maintaining her inner vision of her place and purpose in life–and succeeds despite antagonism from envious classmates and Miss Minchin, who, by the way, is one of the great villainesses of the English novel.

- Middle Build – When news of her father’s death leaves Sara alone and destitute, and Miss Minchin relegates her to servant status, Sara must maintain her inner standards secretly or else succumb to the hardships of her new status. She holds to her standards of how a real princess would behave, and shows others how to do the same, unknowingly invoking the concern and help of admirers around her.

- Ending Payoff – In the MOVIE, after suffering some discomfort and hardship, Sara awakens to a room full of gifts and luxuries from the stranger who’s been watching her from next door. When, unbeknownst to her, her father turns up alive in that same next door house, they are reunited joyfully and the evil Miss Minchin becomes a chimney sweep.

- In the NOVEL: When Sara’s abuse at Miss Minchin’s hands comes close to killing her with starvation, exhaustion, and exposure, Sara must choose whether to carry on or give up. Her steadfastness attracts help from the next door neighbor, who provides for her, not knowing who she is. He turns out to be her late father’s best friend, who adopts her and restores her father’s fortune to her.

The Principle – Anne

My study this season is the differences between novels and their film adaptations. It’s important to understand right up front that movies based on novels are transformative works. The artistic sensibilities of screenwriters, directors and actors–as well as all the other hundreds of people who work on a single movie—all come into play. They transform the story in large and small ways, for a host of reasons.

Novels are created more or less by a single mind, a single imagination. Yes, there are editorial passes, and often an author’s original vision will wind up being something quite different, but still, there is generally only one name on the book cover.

I’m not here to say that novels are inherently better than movies, or vice versa. They are very, very different art forms. Turning one into the other absolutely guarantees that the original will be changed. But I’m really interested in why people who love a novel are almost always disappointed in its film adaptation.

This version of A Little Princess was well received in 1995, with a critical metascore of 83 out of 100. Taken on its own, it’s a charming little sentimental historical story, and it works pretty well.

But for fans of the novel–like me–it was a serious disappointment. Why? Because it lacks the gravity and emotional impact of the novel. It feels lightweight and unimportant. I want to take a few minutes to talk about why.

- First and most egregiously, as mentioned, they changed the ending. Reports of Captain Crewe’s demise turn out to have been greatly exaggerated.

By contrast, in the novel, Sara’s father really dies. While Sara is eventually restored to social status by her father’s friend, that restoration is incomplete–she’s still an orphan. The ending is happy but bittersweet. The movie hits a reset button, and gives us an ending that’s sickly-sweet.

- Another striking decision of the filmmakers was to show Sara going back on her morals under duress, and playing a couple of mean-spirited tricks. She frightens mean-girl Lavinia with a pretend curse to lose her hair–which inexplicably actually comes true–and she dumps ashes down the chimney, ruining a whole room in Miss Minchin’s very clean house. (The fact that she and Becky, as the house servants, will just have to clean that mess up is glossed over.)

In the novel, Sara is tempted a couple of times, but never indulges in petty retribution. As she approaches her lowest point, she has a single moment of complete despair, but she takes it out on her doll, in private.

- A third filmmaking choice was to amp up the obviousness. Sara’s internal, moral heroism wasn’t enough, so they added a police chase and a nighttime escape between slippery rooftops, ending in a death-defying moment of hanging by her fingertips from a wet ledge.

In the novel Sara’s heroism plays out entirely in simple everyday acts of kindness, and courage in the face of extreme hardship, and is more valuable for that reason.

Apparently, comic relief and romance were felt to be missing too, because they took the character of Miss Amelia and made her into a running fat joke, then gave her an unnecessary romance which was presented as ridiculous, presumably because she is a fat woman.

Why do these changes matter?

Mostly because they muddy the genre. In A Little Princess, the novel, we have an excellent, clear example of a Status Admiration story. Sara starts high, suffers terrible losses and goes very low, but never loses her moral compass. Like a true Admiration protagonist, she endures external changes without changing internally, while her steadfastness changes the people around her. Those people reward her by repaying her goodness in the end.

For instance, she gives hope and joy to the abused scullery maid Becky. She helps poor dull-witted Ermengarde find a way to please her studious father. She ultimately gives Miss Amelia the strength to stand up to the awful Miss Minchin. When she’s starving herself, she saves the life of a starving beggar by giving away almost all her food. Every one of them plays a role in Sara’s restoration.

The movie, by contrast, tells more of a Worldview story. Sara learns lessons about poverty and human nature, but the movie reduces her to a typical girl in a maturation story by having her act out against her lot in life with pranks on the people who are meanest to her. It erases her Status Admiration traits.

Similarly, Sara in the novel imagines herself as a princess in her darkest hours not because she longs to have the nice possessions her father once lavished on her, but because to her a princess represents kindness, generosity, nobility, and good character. The movie reduces that belief to the idea that girls are princesses because their fathers dote on them.

The movie has to torture credibility in order to get Sara and her amazingly-still-alive dad into adjacent houses but then keep them from discovering each other for almost half the story. He’s temporarily blind. He has amnesia. There’s mistaken identity at the army hospital. Somehow, though he’s in the British Army, he’s in a New York hospital. Somehow, he has an American daughter. There are a LOT of coincidences, all centered around illogical elements that the filmmakers seem to think a young audience won’t notice or care about.

Why do movies make changes like this to great novels?

In this case, the novel is old-fashioned. Maybe it needed “updating.” Young readers of the early 1900s were less protected and were much more likely to have had direct experience of death in the family than an American moviegoer in 1995. Perhaps the actual death of parent was deemed too traumatizing for that audience.

Hollywood movies–and this was Alfonso Cuaron’s first–are constrained by all sorts of calculations to maximize the potential audience. Popularity generally means a lack of subtlety. Nuance gives way to the obvious.

Whatever the case, the original novel is profound and indelible, whereas the Cuaron film is merely charming. Possibly touching. Sweet and nice. I know Kim has more to say about this, too.

To sum up, the movie pulls its punches by smoothing over Sara’s genuine losses and hardships to the point where they barely seem to count. It injects comedy hijinks and an improbable action sequence, and implies that “nobody” wants a serious, internal genre story about a somber and genuinely principled little girl.

The thing is, as novelists, we don’t have to pull those punches. We don’t have to appeal to millions. Only to thousands. We CAN write novels that read exactly like a movie, but should we?

We can go deeply and directly into characters’ thoughts and motivations. We can take more than a hundred minutes to tell our stories. I’m not advocating for needless length or Victorian-style exposition. But we CAN give our characters and controlling ideas more space than a movie has to breathe and grow in the reader’s mind.

I think it would be incredibly cool to see a novel of mine made into a movie, but that’s not my goal in writing. I’m going to continue to explore the differences between novels and movies adapted from them this season so that I can really understand what makes a novel worth writing for its own sake.

Kim – I agree with everything you said, Anne. One difference that bothered me were Sara’s moments when she stood up to Miss Minchin. In The novel they were nearly always in front of the other girls. Whereas in the film they were not. Two specific moments come to mind:

- The French lesson

- When Sara reasserts that all girls are princesses

Because these moments were more one on one in the Film version, the power struggle between Sara and Miss Minchin wasn’t as, well, powerful. I think moments like this in the novel also help establish and solidify those Status-Admiration Life Values that we miss in the film. Such an interesting comparison.

Leslie – That’s a great point, especially because what we usually see is that the Status-Admiration protagonist inspires those around them. Sara does that to a certain extent with the stories, but the really heroic acts of speaking truth to and standing up to tyrants don’t happen in front of the other girls. And I agree this becomes more of a Worldview story, but Sara lacks a mentor who is present and guiding her to accept seeing the world differently. Neither genre is executed well.

Jarie – Paternal Love

This season I’m looking at love stories to get a better idea on how to use this best selling external genre as the story spine for my memoir. Thankfully, most stories have some sort of love in them albeit not strictly of the obsession, courtship or marriage variety that make up the Story Grid Love Genre.

Love, as they say, conquers all and that’s part of why A Little Princess tugs at my heartstrings. Our protagonist, Sara Crewe, is an imaginative young girl, whose father is a wealthy English widower. They live in India and that affords Sara with a wealth of sights and sounds to fuel her imagination.

It’s clear that Sara’s father adores her but war has broken out (in the movie version) and he must send her away to boarding school, where to show his love he spares no expense for her comforts. He gives her a doll that can magically transport hugs between him and Sara. This doll will be the only thing Sara keeps during the ordeal to come.

Ironically, it’s her father’s “spare no expense” show of affection that will get Sara in trouble since it’s this wealth that makes the school’s headmistress, Miss Minchin, jealous of her wealth.

Often, you see paternal love displayed this way. A loving father, instead of sacrificing career or glory, instead, materially provides for his loved ones but is still absent. There is no doubt that Capt. Crewe loves his daughter but he also loves his country and that seems to outweigh his love of Sara, although he is conflicted about leaving her.

Now, during this time in history, it was common for parents to send their children to boarding school. So this is not uncommon yet as the only parent, you would think that loving your daughter, after she has lost her mother, would override duty to country. Maybe in present day that might be the attitude but at the beginning of the 1900’s, that was a perfectly acceptable thing to do. I’m sure that for 1900’s English society, that was even construed as love for one’s child.

Anne – You’ve expanded on my sense of one of the main problematic differences between the movie and the novel here, Jarie.

The movie makes Captain Crewe the hero. In the novel, Sara is clearly and explicitly stronger and more principled than her own father. He loves her and is kind, but he’s described in the novel as young handsome, and carefree, viewing his daughter as a pal and a companion. He’s no longer a soldier, it’s not in wartime–he’s described as a gambling fool who recklessly lost his fortune. It’s implied that though he loves and misses his daughter, he’s having a pretty good time back in India without her. His relative moral weakness serves to really amplify Sara’s moral strength.

Jarie – This movie definitely has the Father as Hero vibe to it and maybe it’s directly targeted to the US audience since US audiences love a happy ending.

So what does A Little Princess teach us about how to write Paternal Love into our stories?

There seems to be three types of paternal love story lines. One that is a Call to Adventure (A Little Princess, Kramer vs Kramer), one where he has to be the primary caregiver (Mr. Mom), and the third an outsider watching it all happen (Mrs. Doubtfire, Father of the Bride).

The conflict in a call to adventure paternal love subplot is the father’s desire for external fame, fortune, or prestige that pulls him away from his children in the name of duty, honor, or providing for them. The father must then decide what path to pursue. Does he venture out to seek his fortune or stay to take care of his family? That’s the question that is raised in Kramer vs Kramer as an example.

The external quest must be plausible for the timeframe of the story. Would the call of war be as applicable today as in the 1900’s? I’d say so. The same could be said for going far away to secure work to provide for your family or ascending the career ladder.

If you’re going to write a subplot (or main plot) that deals with Call to Adventure Paternal Love, then here are some conventions to consider:

- The best bad choice the father makes must be believable for the timeframe. War is always a good one to choose. A risky business venture is next as long as it’s the only way to provide for his children.

- The tension raises if the mother is somehow not in the picture. She could be deceased or otherwise not available. If she is around, then some sort of tension should exist between them. Either divorce or infidelity.

- You can raise the stakes if the father has an obsession or flaw that drives him to pursue an external success to validate himself since the love of his kids is not enough.

- In the end, the lesson is that pursuing the external goal was not worth risking losing the love and time spent with his kids. The ending can either be happy or sad.

For a Call to Adventure paternal love sub-plot, it always seems to come down to: father pursues fame, fortune, or prestige at the expense of spending time with his children only to realise that no amount of fame, fortune, or prestige can replace that time lost.

As for the other two: Primary Caregiver and Outsider Looking in, I did try and think of some conventions that apply.

Primary Caregiver:

- The traditional mother/father role is reversed due to divorce or death or economic hard times.

- Gender stereotypes and social norms provide conflict that must be overcome

Outsider Looking In

- Gender stereotypes and social norms provide conflict that must be overcome

- Father is striving to gain redemption or father wants their worldview acknowledged

What do you think? Any more good examples of Paternal Love sub-plots or types? If you have any, please tweet us or share it in the comments.

Valerie – I just want to jump in for a quick second here since we get a lot of questions about this at Story Grid. When Shawn talks about the love stories as a genre, he means those that involve the possibility of sex. Jarie is talking about parental love—and he’s right, the love between Sara and her father is what this is all about—but within the Story Grid genre clover this would fall under the society > domestic content genre.

Jarie – So in the Society > Domestic content genre, I guess this would be a scene type. Like Father Goes off to Adventure or something like that.

Leslie – POV, Magical Realism, and Adaptations

Point of View

In an internal genre story, it’s really useful to have some kind of omniscience because we can see the difference between what the protagonist is thinking and feeling to compare to what they say and do. That doesn’t always translate well to film: We get pensive looks where we must intuit what Sara is thinking, or she in essence speaks her thoughts, but this is not the same. In the novel, we get to know Sara through her thoughts and understand that she is mature and sophisticated for her age. This is one way the author sets up Sara’s arc and makes it believable. Of course we know this. The written form of a story is almost always better than the movie. But as Story Grid editors, we don’t stop with that assessment. We’re driven to get to the bottom of it. Clear POV choices are one of the ways the novel offers more than the film. But beyond that, it’s really important that we understand that POV and narrative device choices aren’t just about which pronoun we use to refer to the protagonist.

Anne: Getting that narrative omniscience (or better still, that free-indirect style) across on film rests almost wholly on great acting. Very very few actors young enough to play a child hero like Sara have those skills, and certainly the star of this movie wasn’t up to the challenge.

Leslie: In the novel, we have an overt narrator, but she (feels like a fe minine voice to me) is not identified. Someone is speaking to us. We might imagine someone like Sara telling this story to a young girl to help her through a sad or hard time. But we don’t get that sense in the film. It feels more like we’re eavesdropping on the events of Sara’s life, but no one is guiding us. In the novel, we see events outside of Sara’s perception, but it’s all cast in a magical sense. A benevolent storyteller who doesn’t want us to lose heart serves as a mentor, fortifying and inoculating us against hard times.

Why change the story from the book? Omniscience is hard to do in film. Global internal genres are generally more difficult to portray, and we often see some kind of framing story, nonlinear structure, epistolary elements, or other narrative device that stands in for omniscience. (Examples from last season include Kim’s picks A Man Called Ove and Fundamentals of Caring.) I think the story loses a lot with the absence of this element in the, more than the general rule that the book is better than the movie.

Adaptations Generally

As Anne explained, Sara’s father lives in the film, and in the novel he doesn’t. Sara is saved by the man who got Captain Crewe into trouble, which allows a sort of redemption for him. I wonder if the rationale behind the choice is similar to the way that Grimm’s fairy tales and other folktales have been altered, or sanitized, for modern children because they seem too violent and scary. Regardless, the result here is that Sara doesn’t really lose anything, a key convention of the Status Admiration story. She goes back to life as usual, in fact she gains a new sister.

Here are a few other moments that didn’t work from my perspective.

In the novel, Sara doesn’t do anything extraordinary, what I mean is outside of what a typical young girl could do. There is a sense that magic is present, but for example, she doesn’t leap grab the side of a building in the rain and pull herself up, a feat that would be difficult for almost anyone. That scene felt out of synch with the rest of the story.

Also, the scene where Sara gives the bun to another girl isn’t as meaningful or powerful as it is in the book because there is no setup to show how hungry Sara truly is, like it’s done in the book. We miss the more lengthy conversation with the baker, who is inspired by Sara’s sacrifice.

It’s snowy and cold in some scenes, but we don’t really see/experience how cold Sara is, how her shoes are too small for her and don’t keep her feet dry (though this could be set up because of how the girls walk carelessly through the water early in the story).

Much of this is probably due to time and budgetary constraints.

One minor point is that Lavinia’s change at the end, coming to love and appreciate Sara is in no way earned.

Something interesting to me is that I found the book more believable than the movie. Magical realism is a great subset of the realism genre, but the story and magic within it needs to be internally consistent. The question is not, do these events make sense in our world? but does it make sense in this world that’s been set up by the story creator? The magic appears in a haphazard way within this story and doesn’t seem to be grounded in an internally consistent logic.

Jarie – Leslie, what do you think about the content of the fantasy stories? The story line about the prince and the princess seems to parallel the real story.

Leslie – I’m so glad you brought that up because, despite its shortcomings in terms of the culture, I think including stories that mirrored what was happening in her father’s life was an interesting innovation.

Anne – It’s important to note that in the novel, every story Sara tells herself or her schoolgirl friends is more typically from European folklore. The recreation of the Indian classic story is the movie’s way of trying to show the life in India that Sara left behind. Some critical viewers today see it as orientalism, or as exoticising Indian culture, and that crossed my mind as well. 1995 was a long time ago in cultural years. Oddly, I felt that the novel’s treatment of India and the Indian character Ram Dass was a bit less problematic than what the movie did 90 years later–because he was a real, ordinary Indian man, not a fantasy figure.

Leslie – If we look at a spectrum where the adaptation of novel to film, as in A Little Princess, is on one side, and the adaptation of say a classic to a contemporary story or using a masterwork to tell your story, like taking the Bhagavad Gita and converting it into The Legend of Bagger Vance as Steven Pressfield did, you can see how many of the challenges the writer faces are similar. So where should you start? I recommend starting by identifying what is most interesting to you about the story. But then go deeper. What are the decisions the author of the original made? What could that look like in my story? How to innovate? How to subvert expectations in a good way?

The takeaway here is not that this is a terrible adaptation. People enjoy it, especially the target audience. I enjoyed much of it (and not just because the actor who plays Captain Crewe also plays Ser Davos, the Onion Knight, on a certain series I love). The point is that the story could be stronger. As Anne mentioned above, the emotional impact could be dialed up to make this a great story, which is exactly what the author of the novel did.

Kim– Yes, I completely agree. The father/amnesia plot was much less believable for me than the father’s business partner searching for her to make amends. Don’t get me wrong, as a girl whose father died when she was young, I love that Sara gets her daddy back, but maybe I’m also annoyed because it’s all a bit too perfect. It doesn’t ring true in the Big Meta Why sense.

What’s the prescriptive tale of the Film version? When tragedy strikes and misfortune befalls you, stay reasonably good and your dad will come back to you … ?

Sorry, folks. Ain’t no such thang. It’s beauty for ashes, not zero ashes.

Whereas the novel does something so much more satisfying.

Tragedy does strike and misfortune will come, but if you stay true to what you know is right, you will rise, and the strength and love you show will spread.

Maintaining your moral code doesn’t magically fix things, but it will always serve your greatest good.

But I have to admit, even though I like the novel more, even though the film ending is too saccharine and makes me slightly bitter about the message it’s sending, I still effing tear up when her dad calls her name and they embrace.

“Sarah!”

Ugh! So many conflicting emotions! Haha. That moment is nearly on par with Rocky Balboa’s.

“Adrian!”

Valerie – Empathy

For my own film choices in season 5, I’ll be studying one particular genre (psychological thriller) because that’s what I’m writing. But for the other 12 films this season, I’m going to look at empathy. I want to examine how screenwriters have, or have not, created empathetic protagonists, and I want to understand how this affects the story as a whole.

But first, let’s take a quick look at what we mean by empathy and why having an empathetic protagonist is important.

Empathy is when we can understand, relate to, and share the emotions of another. It’s when we know what it’s like to actually feel the way the protagonist is feeling. That makes it very different from sympathy. We’ve heard Shawn say that “specificity begets universality” and part of what he’s getting at with this is empathy. A protagonist is going through a specific experience that we may not have gone through, but that experience gives rise to feelings that we have had in our own lives.

Empathy is the thing that engages the audience in the story; it’s what makes us care about what happens to the protagonist. It’s what makes us cheer them on and hope they get their objects of desire.

For example, I have never been a boxer or even an amateur athlete. I’ve never been a man and I’ve never been to Philadelphia. But I know what it feels like to want something more than what I have, to want a better life than I have. I know what it’s like to go up against such incredible odds that going the distance is a win. That means I can easily relate to Rocky Balboa. I have huge empathy for him. I’m cheering him on because a win for him is a win for me. If he can do it, I can do it.

And this is what story is all about, isn’t it?

Story is about change, it reflects society, it teaches us something about what it means to be human.

This is one of the many things that The King’s Speech did so well. I’ll spare you another big monologue about how amazing that film is, but seriously it’s a brilliant example of empathy. None of us has been the King of England, but we’ve all suffered at the hands of others. In fact, A Little Princess uses some of the same elements as The King’s Speech to tap into empathy, although the approaches couldn’t be more different; we’re in the middle of Sara’s childhood whereas we’re reflecting back on Bertie’s which allows us to see how the Nanny’s behaviour affected him. It’s heartbreaking.

Ok, so how is empathy created in A Little Princess?

It would be easy to point to facts like Sara is a child (and therefore powerless), it’s war time, her mother is dead and her father has had to leave her at a boarding school. But these are things that create a situation where empathy can bloom, but they don’t in and of themselves create empathy.

I think Frances Burnett Hodgson does a better job than the film to be honest, and this is partly due to the screenplay but also due to the acting. I don’t want to get into the quality of the performance because that’s irrelevant to a novelist, but we can still learn something here. In a novel, readers can get inside the head of the protagonist and so Hodgson can show us Sara’s struggle with the new rules and her new environment. We’ve all been the outsider and so we can more easily relate to how Sara’s feeling. Harry Potter, and a bajillion other children’s books, use the same trick.

But even with this situation, Sara isn’t a particularly empathetic character until the end of the story. She’s just too good.

I get that Hodgson was presenting the ideal way a girl should behave—like a little princess, right?—but we don’t actually behave this way. People act much more like Anne Shirley or Harry Potter, or Dennis the Menace…or Calvin. So, Sarah’s sugary sweetness is a barrier to empathy. I kept wanting her to lash out — and yes, she did put a hex on Lavinia, and she does dump the coal, but to me that felt like it was too little too late.

Anne pointed out the inconsistencies here with the novel and I wonder whether it was an attempt to make Sara more relatable. It didn’t quite work, but maybe that was what they were going for.

There’s a certain amount of subjectivity here of course. But for me, the emotional connection didn’t happen until the end of the film when Sara’s father doesn’t recognize her. This is about abandonment, and whether we’ve been abandoned or not, it’s a primal fear that we’ve all had. Even though her father left her at the school in the beginning hook, he didn’t abandon her. Here, her hopes are raised only to be dashed. She’s being rejected by her only surviving parent. Holy cow. Powerful stuff.

Unfortunately, it doesn’t last very long, so there’s no real tension built up which means there’s no real catharsis. But, it’s on the right track and you might still need a tissue.

Final Thoughts

Kim – The Sarah Crewe in the novel reminds me of Jane Eyre in a way, this inborn self-respect and deep moral code that refuses to compromise, even at a young age. It may not be that the shadow doesn’t exist, it’s just harnessed–stubbornness perhaps?–to uphold their moral code. And this is the perfect protagonist for an Admiration story, because we admire them and strive to be like them. Or at least I do, and I’m so grateful to have these heroines to mentor me.

Anne – I’ve realized something else as we’ve been talking: the Mentor figure is a key element in internal genre stories, and it strikes me now that Sara Crewe is “self-mentored” in the novel, something that might be seen as a story flaw–it’s certainly part of why Valerie finds her hard to believe.

On further thought, though, I could argue that in the novel Sara’s mentors are explicitly books. She’s an avid reader, and her moral core is built from a combination of a loving parent, attentive care early in life, and a fantastic education from great books.

Listener Question

To wind up the episode, we take questions from our listeners. This week’s question comes to us on the Story Grid blog, from Jim Luther. Jim writes:

“Shawn, you’re very clear that each genre has specific obligatory scenes that are critical for the book to “work.” I get that, but have we conditioned our readers so much that they would get, perhaps, a little bored looking for that necessary obligatory scene that it becomes too predictable?

For instance, in thrillers you need the hero at the mercy of the villain scene. Wouldn’t readers become so conditioned that they know it’s coming and know that the protagonist will get out of this no matter how powerful the villain is? Would there be other ways to accomplish this? For instance, maybe the protagonist is at the mercy of the villain, but she doesn’t know it. I suppose I may be answering my own question in that you say how important it is to surprise the reader in every scene.”

Leslie – This is a great question, Jim. The short answer is that readers of a genre never seem to get tired of the obligatory scenes—when they are executed well, and to me that includes two elements: first presenting the necessary ingredients of the genre and second, do it in an unexpected way. The same, but different. These scenes are the way the life values in the story. This is how books within a genre are in conversation with one another, and really, those obligatory scenes, particularly the Core Event, are the heart and point of the story.

The genres as Shawn identifies them in The Story Grid are connected to human needs. So we go to stories for entertainment, but also often to satisfy our need to understand basic human problems—we might not even realize that we’re doing that. The beginning hook establishes the basic problem, it complicates through the middle build, and reaches its peak in the ending payoff with the Core Event. That is when the life value changes and the Core Emotion is at its peak. The Core Event in a Thriller, as you mentioned, is the hero at the mercy of the villain scene. If that doesn’t happen, then the original problem isn’t fully resolved in a way that makes sense. And by the same token, if you include it but in a way that is precisely the same as it’s been done elsewhere, it won’t be satisfying then either. To innovate, consider what is your unique take on these scenes.

Now, does this mean you can’t tell a good story without hitting these notes? Some writers choose to break structure because they want to say something about the cultural narrative or perhaps about stories generally (the documentary Examined Life is an example of this). There is value in this level of experimentation, and you can take that route, just realize that it changes the way the reader receives the work, and therefore the ideal reader for your story and the size of the audience. So understand why you’re doing that and what you hope to achieve.

Key Takeaways: Avoid these pitfalls: (1) omitting the scene without a good reason (sometimes this is resistance, so really interrogate your motives here) and (2) writing a cliched scene that’s been done over and over again.

To solve these problems, I recommend reading deeply within the genre to understand what’s been done and what readers expect.

Then, read widely outside your genre to find connections and different ways of looking at obligatory scenes.

Finally, make sure your story includes these necessary ingredients unless you are intentionally breaking structure and either way, find your unique take on these ingredients or their absence.

If you have a question about any story principle, you can ask it on Twitter @storygridRT, or better still, click here and leave a voice message.

Join us next time as Leslie explores what makes a great epic action film with Thor: Ragnarok. Why not give it a look during the week, and follow along with us?

Your Roundtable Story Grid Editors are Jarie Bolander, Valerie Francis, Anne Hawley, Kim Kessler, and Leslie Watts.