This week we’re going deep into the dream world with Anne’s pitch, Inception, as a great example of nested storytelling. This 2010 science fiction heist film, nominated for 8 Academy Awards—four of which it won—was written and directed by Christopher Nolan.

Now, we always try to discuss our movie in a way that lets listeners follow along even if you haven’t seen it yet, or lately. In this case, though, we really want to encourage you to go and watch Inception before proceeding.

Why? Partly because the only way you’re going to follow the discussion of this complex movie is to have already seen it. And besides, there’s a kind of revelation element that we don’t want to ruin for you. This is a movie where spoilers will really spoil the fun.

Genre: At one level, this is a straight up Crime story in the Heist subgenre, where professionals team up and execute a complex plan to defraud or steal from a mark either for revenge, as in Ocean’s 11, or—in this case—because they’ve been hired by someone powerful to do a job that nobody else can do.

Because the science fiction premise is so complex, the movie spends the first 15 minutes on a kind of action prologue, where two main characters are effectively auditioning for the heist to come. It establishes the principal characters, the background of the job, and some of the key rules of its world. So I’m going to argue that the external genre beginning hook doesn’t officially start till minute 16.

Here’s the purely external heist story in brief. And this is interesting because stripping it down like this revealed how pure the external global story is–it makes almost perfect sense without even touching on the strange dream technology the team uses, or the deep philosophical questions about reality that I think form the movie’s enduring fascination.

- Beginning Hook – When a powerful energy tycoon offers exiled American professional thief Dominic Cobb a way to return legally to the US, he must agree to undertake an impossible reverse theft called Inception, or else accept that he will never see his children again. He takes the job and assembles his team.

- Middle Build – When Dominic’s ex-wife Mal begins showing up during the team’s rehearsals, distracting Dominic, he must to find a way to ignore her and carry out the heist, or risk failure and permanent exile. He pretends there’s no problem, but when Mal drags Dominic away at the critical point in the Inception, Dominic must break from her or else lose both a team member and the mark, and fail at the job. He leaves her, the team survives, and the job is successful.

- Ending Payoff – Saito, the energy tycoon, honors his word and uses his worldly power to clear Dominic’s name with a single phone call. But when Dominic returns home, his experiences have made him question the reality of his own perceptions. He decides to accept the apparent reality, and embraces his return to his children. The story ends without definitively answering the question.

All of these events are happening in the context of scenes where what’s real and what’s a dream is constantly in question. The purpose of the heist–the Inception–is to use military dream-sharing technology to plant an idea in the mind of the mark so that when he wakes up, he’ll decide to break up his father’s giant conglomerate. This is presumably for the benefit of mankind, but we’re never sure whether it isn’t really just for the benefit of Mr Saito.

But the other story, Dominic Cobb’s internal story, is a morality plot, revolving around an experiment he and his wife did deep in the dream state that resulted ultimately in her suicide in the waking world, believing that she was still in a dream and that dying in it would wake her up. Dominic blames himself for her suicide, and her constant presence in his subconscious mind, which he can’t control, is the antagonistic force that rules the middle build.

His choice at the global climax is to leave Mal–that is, her presence in his subconscious mind–deep in the limbo state, where the image of her dies. That’s the sacrifice he makes in order to rescue Saito, who has been trapped in his own limbo realm. Whether this is an altruistic choice or a selfish one remains ambiguous–after all, Dominic is depending on Saito to clear his name so he can return home to his children.

So is it really a redemption story? Or does Cobb ultimately decided not to decide, and live in the illusion of reality? In every sense, the internal genre story is left with an ambiguous ending.

The Principle

Anne– After watching this movie a few times over the past week, I’m realizing that what I SHOULD have proposed as a story principle is the use of distraction! This movie has some of the best and most expensive use of exposition as ammunition I’ve ever seen.

Valerie – Because I just spent a week with Robert McKee, I’m going to be talking about him a bit this week! I think Anne’s observation is right on the money here. McKee says that “The Dream Sequence is exposition in a ball gown” and that when used, they’re “usually feeble efforts to disguise information in Freudian cliches” (Story. p. 343). Here we have a whole story built around dreams! The only question that matters of course is does the story work or not. But, a lot of the scenes right up to the midpoint shift are designed to explain the rules of the dream world to the viewer, and establish the stakes. The filmmakers had the benefit of Leonardo DiCaprio, Oscar-winning special effects, an enormous location shooting budget, and action movie cliches (tropes? standards?) like a foot chase through a crowded market in Mombasa, Kenya, so, all the exposition is compelling and entertaining.

Anne – However, the story principle near to my heart–and the reason why I LOVE this movie and pitched it this week–is the narrative device of nested stories. There’s no hard and fast definition for this term, and it’s of course not an “official” Story grid term, but my idea was that the dream within a dream within a dream put it into the mind-bending category of a story within a story (times four, in this case).

I’m writing a novel myself with a structure of separate but interwoven stories, so I had a personal stake in making a study of Inception. Some definitions of nested stories include, for example, The Arabian Nights, where a narrator tells the story of a storyteller telling stories. The framing narrative is that her telling a new story every night is the only thing keeping her alive. That is, there’s an external plot that connects all the stories she tells. But the stories she tells within the frame are standalone.

Valerie – When Anne pitched Inception as an example of nested stories, the first thing I did was ask her to define what she meant by nested stories. To me, it means a story within a story; and The Princess Bride is an excellent example. There, we have a grandfather telling his sick grandson the story of the princess bride. That story is mildly affected by the reading of the story in the book, as the grandson changes his mind about love stories. This is simply one full story within the slender frame of another.

I also wondered whether Inception does have nested stories, or were they subplots. As Anne said, we’re not dealing with an “official” Story Grid term so really, what we call it is up to us. It’s the principle we need to study and understand so that we know whether we want to use it in our own writing, and if so, how.

Anne – While most sources I could find defined the term “nested story” to include the single-frame, single-interior-story framing device, the definition I’m interested in is the device where several stories within the main story are connected causally…where the interior stories affect each other and have hidden links.

The four dream levels of Inception, and what happens in them, are all causally related. The heist the team is undertaking is incited by Saito’s offer in the real world to clear Cobb’s name and let him return to his children in the United States. Once they all go under on the 10-hour trans-Pacific flight, each level of the dream is intricately bound by the actions and choices of the one above it.

So when Yusuf, who is dreaming the first level, crashes the van too early, Arthur, in charge of level two, must take emergency action to protect the dreamers still dreaming in level three.

It’s true that all four “stories” are in service of the heist itself, and in that sense this is just a linear crime story, as laid out in the summary I gave.

But here’s what I’ve learned as a novelist by studying this movie masterwork:

First, that a nested structure is excellent for conveying complex philosophical or spiritual ideas. In fact I’m not sure you would use it for any other reason. The structure itself is a metaphor. This is probably why great spiritual and philosophical works like Plato’s Phaedo and the Mahabharata use it.

Valerie – I’m going to jump in for a quick minute here, Anne. I’m not sure I’d accuse The Princess Bride of conveying complex philosophical or spiritual ideas. I see where you’re coming from, completely. But I think it’s a device that is wider reaching (and one that can be used as a crutch if writers aren’t careful).

Anne – No, I agree. I think the simple framing story device of Princess Bride–or Bridges of Madison County, for that matter–is useful for creating things like dramatic irony or mystery. What I’m interested in here are the multi-layered tales within tales within tales. I mean, why complicate your story like that unless the narrative device serves as a metaphor for levels of reality, or of perception, or something equally “deep”?

Which is what I was thinking of when I decided that the second thing a novelist can learn from studying this device is that it seems to require a clear overarching external story within which to explore those deep philosophical waters. Otherwise, just write a think piece. Stories don’t get more external than Crime/Heist, a genre that provides intense narrative drive with a ticking clock and high stakes.

Third, nesting stories are stories that fascinate the reader or viewer and endure in the mind. They’re stories that support multiple readings and viewings, and each time, more layers and details emerge. I’ve watched Inception five times altogether, and I still feel I’m just beginning to grasp it all. I’m not one bit tired of it yet. Well, the middle build might be starting to show its weaknesses…

Finally–and by no means least–even if you have no plans of writing in this realm, it’s an amazing training exercise to step back from the cool effects and mind-boggling big ideas, and learn to see the tropes, conventions and–dare I say it?–the clichés at work that make this weird-ass movie totally recognizable as a popular entertainment.

There’s a good Wikipedia article on story-within-story that lists a ton of interesting examples in literature and film, Inception is one of them.

Another worthwhile article is on Tor.com, where author Brad Kane places framing devices and nested stories together in a continuum, which makes sense. They’re related. After listing a number of examples from literature, film and television, he says this about the peculiar narrative-drive properties of this story type:

Why do framing devices work so well? Perhaps it has to do with the simple idea of suspension of disbelief. As readers and viewers, we have to suspend our knowledge that fiction is fake when we read a book or see a movie. That’s how we’re able to “get into” the experience. But when we experience a story within a story, that transition is more natural. It’s as if once we make that first leap of the imagination, we get more easily swept away with each new layer.

And when it all ends, we find ourselves back in the first frame, often surprised to remember where it all began. That moment can be powerful, and speaks to the intoxicating power of a well-told story. Perhaps that’s why framing devices have been around for as long as stories themselves.

Valerie – As you’ll remember, I spent last week in Los Angeles at the Robert McKee seminar, so I didn’t work with Anne the way we normally would have. She gets full credit for having pulled this together! What I wanted to look at with respect to Inception, is why would a writer choose this style; what does it add to a story and what does it take away?

The bottom line is the same as it always is, of course. A writer would only choose this device if it helps to move the story forward—but it’s not enough to simply state that. What we’re trying to do is figure out how it moves the story forward. How does it create narrative drive?

I think for the most part, Inception employs suspense; that is, we know what Cobb knows. That’s not true 100% of the time of course and a prime example is in the opening sequence where we have an instance of dramatic irony. Anne and I talked about this and she made a fantastic point. She said, “I think we could argue whether that prologue-ish opening puts us in dramatic irony or mystery. We may know a kind of “future” but it seems that Cobb, at least, knows it too, and he knows what it means whereas we don’t have a clue.”

A quick refresher:

Suspense is when the audience and protagonist has the same amount of information. Mystery is when the protagonist knows more. Dramatic Irony is when the audience knows more.

There’s another difference between these three that Robert McKee mentions in Story, but that he talked about in more detail at the Genre Week seminar I just attended. We might as well he benefit from it. Not only is the difference in the amount of information the audience has relative to the protagonist, they also differ depending on the impact they have on the reader.

In other words:

Mystery creates a sense of sympathy for the protagonist, but not much empathy. We don’t empathize with Sherlock Holmes. Suspense creates high empathy and curiosity with respect to how the story will end. With dramatic irony, the audience isn’t wondering how it will end, they’re wondering how and why the character did what they did. This creates a feeling of dread in the audience because we know where the protagonist is heading. For dramatic irony to work, it’s essential to have a compelling protagonist, otherwise the audience won’t engage emotionally. What was anxiety in suspense becomes compassion in dramatic irony.

Testing the Proposition

Jarie – I believe that this is a linear story with a beginning hook flashback and not a nonlinear story. It’s actually a perfect example of a framing story in which there are nested frames that almost adhere to my framing story guideline of Jane Eyre (e.g. Framing stories can be lifted out of their frame and stand on their own). While technically you can lift each “level” out, it’s a little squishy.

The whole frame within a frame within a frame within a frame is an interesting way to tell this story albeit it’s hard to follow at times. Leslie will dive a little deeper into the how to pull this off later.

While I agree with Anne that this has an external Genre of Crime > Heist (since they are pros), that’s not what drives the story. The real driver for me is the internal genre of Worldview > Education.

Inception hits all the Obligatory Scenes and Conventions of Worldview > Education which is presented below:

Obligatory Scenes

- An Inciting opportunity or challenge: Dom getting back to his kids

- Protagonist denies responsibility to respond to the opportunity or challenge: Does not want to do the Saito job.

- Protagonist lashes out against requirement to change behavior: Dom has to do the job — it’s the only way to get back to his kids.

- Protagonist learns what their external Antagonist’s Object of Desire is: Saito wants to break up the company.

- Protagonist’s initial strategy to outmaneuver Antagonist fails: He tries to steal Saito’s secrets and can’t

- Protagonist realizes they must change their black/white view of the world to allow for life’s irony: Dom gives in to seeing his kids, even if they are in a idea.

- The action moment is when the Protagonist’s gifts are expressed as acceptance of an imperfect world: Dom’s ability to go deep into others memory.

- The protagonist’s loss of innocence is rewarded with a deeper understanding of the universe: Dom does not care if he is dreaming as long as he can see his kids.

Conventions

- Strong Mentor Figure: The Grandpa

- Big Social Problem as subtext: Big companies that control the world

- Shapeshifters as hypocrites: Saito just wants Dom to do the job.

- A clear Point of No Return: When Dom accepts the job to do Inception

- Ironic win-but-lose, lose-but-win bittersweet ending: Dom sees his kids but does not know if he is dreaming and does not care.

As we say all the time, just because it meets the Obligatory Scenes and Conventions, that does not mean it’s that particular genre. We need to use another test. For us here at the Story Grid Editor Roundtable, we have chosen Steven Pressfield’s Intro and Outro method or what does the beginning scene step for the ending scene to payoff.

In the case of Inception, the Intro is the flashback scene when Dom is on the beach and sees his kids. This is a recurring flashback for him along with his wife, Mal, who we find out later committed suicide. His life is meaningless and it tortures him that he can’t be with his kids. What this intro scene shows us is that Dom wants to get back to his kids and he clearly did something that is preventing him from that, which we don’t find out until much later.

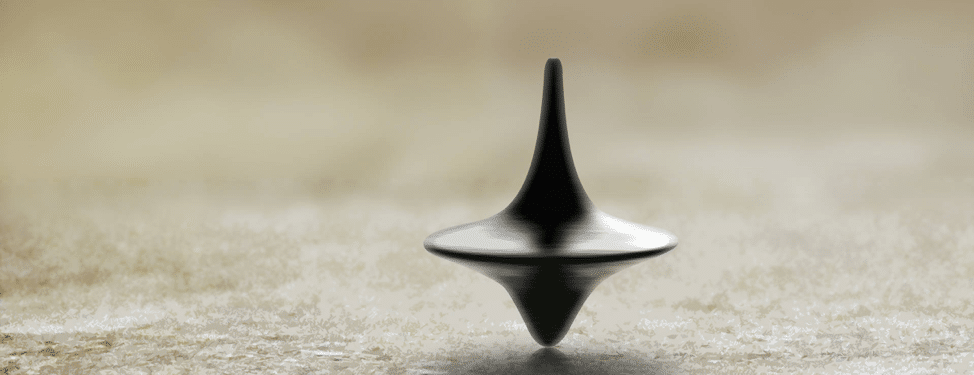

The Outro scene is Dom being reunited with his kids after completing the job. Dom spins his totem top, which was Mal’s, to prove to himself that he is in reality but chooses to ignore the outcome. For him, even if he is in a dream world, it’s enough that he is with his kids. His life has meaning and it’s a lose but win — he loses the real world (implied) but wins being with his kids, even if it’s a dream.

Leslie – There are different types of nested stories, including the following:

- Story within a story, or a typical framing story, e.g., The Great Gatsby.

- Deeply nested stories, ones with more than two levels, e.g., Inception or Cloud Atlas.

- Fractal Fiction with several instances of multiple story levels, e.g., The Neverending Story

- From a story within a story to a separate story or a spin-off, e.g., Fantastic Beasts and Where to Find Them.

How can you write a nested story that works? The nested elements shouldn’t come together in a random way, of course, but what tool can you use to plan and revise your nested story? Orson Scott Card’s MICE Quotient.

On a basic level, the MICE Quotient helps you answer the question, what kind of story am I writing? That question could be referring to any number of topics, including the five leaves of the Story Grid genre clover: content, structure, time, reality, and style. But we might also mean one of the four factors in the MICE Quotient: Milieu, Idea, Character, and Event.

- Milieu stories are related to the setting, for example, The Lord of the Rings.

- Idea stories explore a question to be answered or a problem to be solved, for example, Death Comes to Pemberley by PD James (who killed Captain Denny?).

- Character stories relate to a character who needs to change, for example, Scout in To Kill a Mockingbird.

- Event stories deal with the attempt to restore balance after things have been upset, for example, Master and Commander.

All of these factors appear in most stories, and we can see them in Inception, but one takes center stage and should be related to the Global Genre.

Like so many elements of story, these factors can affect all the other elements of the story. Certain factors go better with particular genre, POV, and narrative device choices, for example. This is another reason to find a masterwork or two to assist you in planning, drafting, and revising your story.

You can craft subplots and sequences using one or more of the other factors, but they should be nested last-in, first-out, like nested code.

Why is that? Card talks about the basic contracts writers make with readers: We will finish what we start, and anything we spend a great deal of time on will amount to something.

Let’s look at how the MICE factors work in Inception:

- Character: Cobb wakes on the beach, sees his children, but not their faces; Saito says, “I knew a man, possessed of some radical notions …” This is the internal genre, which I think is the global one. I disagree with the assessment that it’s Worldview Education because Cobb doesn’t only change the way he sees the world, but makes an active sacrifice. I identify Inception as a Redemption story, but either way, the opening factor is related to character.

- Idea/Problem: Steal secret from Saito. Immediately resolved when they abandon the job.

- Idea/Problem (heist): Saito offers Cobb a job—planting an idea in the mind of the heir to a huge power multinational corporation—that will help Cobb get home to his kids. Resolved when Saito wakes on the plane and makes a call.

- Idea/Problem: Complete team and make plan. Resolved when they get all the members, Eames crafts strategy, and Saito gives them the time and place for the ten hours they need.

- Milieu-level 1: Team begins level one dream on the flight after Robert Fisher’s father dies—rainy city kidnapping (flight attendant still awake on the plane).

- Event: Saito is shot in level one.

- Milieu: level 2: They begin level 2 from the van—hotel (with Yusuf awake in the van).

- Milieu: level 3: Cobb convinces Robert that there has been an extraction attempt and to go with the team into level three—snowy fortress (Arthur left awake in the hotel).

- Milieu- level 4: Fisher is killed in level 3 and ends up in level 4; Cobb and Ariadne follow him.

- Milieu: Resolve level 4: Ariadne kicked with Fisher to level 3.

- Milieu: Resolve level 3: Fisher revived with defibrillator and resolves things with his father. Everyone except Cobb is kicked to level 2.

- Milieu: Resolve level 2: Wake in hotel then kicked to level 1 in the water in the van.

- Milieu: Resolve level 1: Cobb convinces Saito to return. They wake on the airplane.

- Idea/Problem: Resolved: Successful inception

- Character: Resolved: Cobb made sacrifice (letting go of Mal) and is reunited with his children—in a dream or the waking world (we don’t know because we didn’t see the top drop).

*You could also argue that the dream levels are idea/problem factors, the goal of each being to plant one element of the full idea within each level.

What if you’re not writing a complicated nested story like Inception? You can still use the MICE Quotient to help you sort out your subplots and open and close them in a satisfying order. For example, in Pride and Prejudice, you could track the main love story between Elizabeth and Darcy, but also the subplots relating to Jane and Bingley, Lydia and Wickham, and even Charlotte and Mr. Collins.

Kim – Children’s book that uses nesting stories, Charlie Cook’s Favorite Book by Julia Donaldson.

Final Thoughts

Anne – I’d forgotten the MICE quotient, Leslie, so thanks for the reminder.

I sat up half the night last night wondering whether this story’s global genre is Crime Heist or its internal genre, and my sleepyheaded conclusion today is that they’re pretty equally balanced and that your sense of which is more important is going to be entirely personal and subjective.

I disagree with Jarie about the Worldview genre, though he’s made a good case for it. With Leslie, I think it’s Morality/Redemption. Here’s what Friedman has to say about this plot type, which he terms the Reform plot, one of his plots of character:

The reform plot

Somewhat similar is another form of character change for the better, with the difference that the protagonist’s thought is sufficient from the beginning. That is to say, the protagonist is doing wrong and they know it, but their weakness of will causes them to fall away from what they themselves know to be the just and proper path.

Faced with the problem either of revealing to others their weakness or of concealing it under a mask of virtue and respectability, they choose the latter course at the outset. The problem then becomes one of devising the means of forcing their hand, of making them choose the alternative course.

Thus, after having been led to admire the protagonist at the beginning, we feel impatience and irritation when we begin seeing through their mask, and then indignation and outrage when they continue to deceive others, and, finally, a sense of confirmed and righteous satisfaction when they make the proper choice at last. In the maturing plot there is some pity for the protagonist, because they act and suffer under a mistaken view of things, but it is exactly this element which is missing in the reform plot.

The two chief examples of this type which come to mind are The Scarlet Letter and The Pillars of the Community. And in certain respects it resembles the punitive plot in that the protagonist is a pious hypocrite or charlatan impostor of some sort but is different in that he is reformed at the end rather than merely punished.

–Friedman, Norman, Forms of the Plot

Finally, I just want to acknowledge what one Amazon one-star reviewer says. “The plot of this film is way too complex for its own good. It’s as if the writers tried to combine The Matrix with a bank heist film and ended up with a long drawn out gunfight with odd scenery.”

The 8.7 IMDB rating and the Oscar screenplay nomination suggest that Inception had enough narrative drive and satisfaction to overcome that obstacle for a lot of viewers and story professionals, but I think it’s a fair point to make. If YOU want to write a complex nested story in support of a deep idea that might only be able to come across in metaphor, you won’t be writing a story for everyone.

But then, there’s no such thing as a universally appealing story, so, as our Canadian colleague Valerie would say, “Fill your boots.” Write what YOU want to write, and make it the best story you can.

Listener Question

To wind up the episode, we take questions from our listeners. This week’s question comes to us from an event Valerie attended, The Night of Writing Dead event in Pittsburgh in October our in by fellow Story Grid Editor J Thorn.

What makes the 5Cs, the 5Cs? In other words, what makes an inciting incident an inciting incident, etc.?

Leslie – The Five Commandments of Storytelling are distilled from basic dramatic structure handed down from Aristotle and refined by people like Gustav Freytag and Shawn Coyne. Shawn also made the connection to the Kubler-Ross change curve, which describes the steps people move through when they experience grief related to change. So what does that mean? It means that stories are about change and the Five Commandments provide a structure to the process of metabolizing change.

Generally speaking the protagonist is minding their own business, living life, when an inciting incident comes along and upsets the balance. The inciting incident creates a desire and goal to arise within the mind of the protagonist. As they pursue the goal obstacles and tools arise, which we call progressive complications. An unexpected event, or the turning point progressive complication, occurs, forcing the protagonist into a dilemma, which we call the crisis question. The protagonist decides and acts on that decision in the climax, and consequences flow from there in the resolution.

There’s lots more we want to say about these tools, and at the end of season 3, we’ve planned another Story Grid 101 episode in which we’ll break down the Five Commandments. So be on the lookout for that!

If you have a question about nested nonlinear story structure, or any other story principle, you can ask it on Twitter @storygridRT, or better still, by clicking here and leaving us a voice message.

Join us next time to find out whether Leslie can make the case that The King’s Speech is a great example of emotional stakes. Why not give it a look during the week, and follow along with us?

Your Roundtable Story Grid Editors are Jarie Bolander, Valerie Francis, Anne Hawley, Kim Kessler, and Leslie Watts.