This week, I’m looking at The Guernsey Literary and Potato Peel Pie Society, in order to study how a story’s life values are established in the beginning hook. I chose this story because 1) I love it, and 2) it has several similarities to the kinds of stories I write: epistolary, internally driven about what love / family really mean. In fact, at the time of recording this episode, my debut novel According to Plan is up for pre-order and will be officially available in January. Be sure to sign up for my list to find out the moment my book comes out at kimberkessler.com.

This 2018 film was directed by Mike Newell from a screenplay by Don Roos, Tom Bezucha, and Kevin Hood. It was based on the 2008 novel of the same name by Mary Ann Shaffer and Annie Barrows.

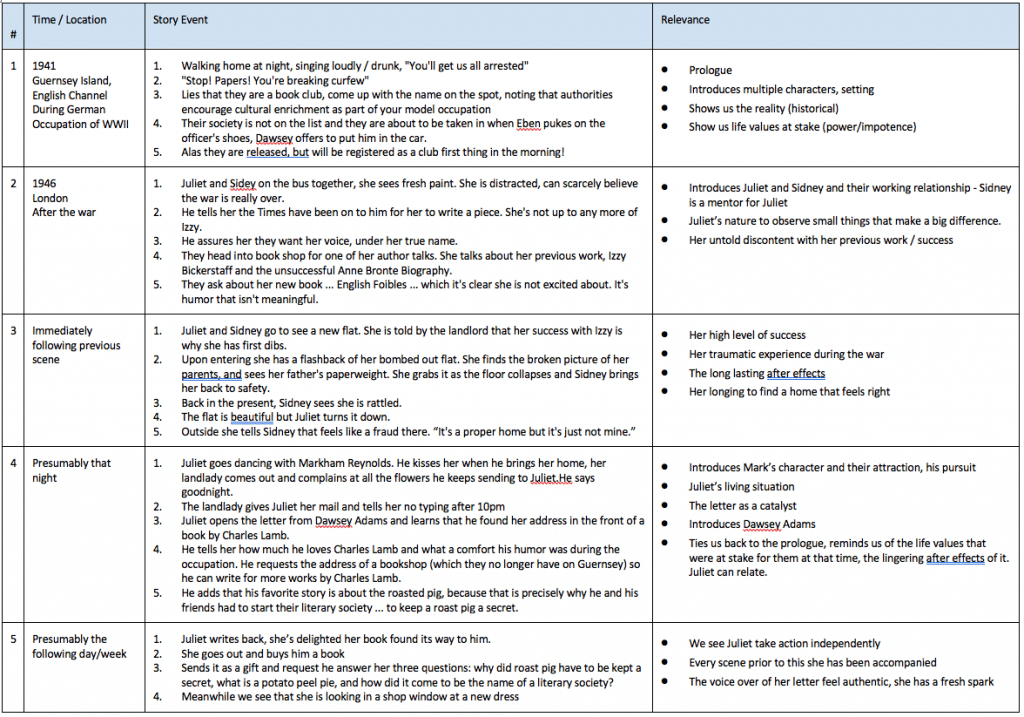

The Story – Film*

- Beginning Hook – Although she is a successful author, Juliet Ashton is struggling to find her way after the end of the war. But when she receives a letter from a man from Guernsey Island, Dawsey Adams, who found her address in a book, she finds new purpose. They continue to correspond and she learns about his book club—the Guernsey Literary and Potato Peel Pie Society—that began during the German occupation. She is so compelled to learn more that she postpones her book tour to travel to Guernsey to meet the members of this group herself. Just as she is to board the boat for Guernsey, her beau Mark Reynolds proposes and she accepts.

- Middle Build — Juliet arrives in Guernsey and meets all the members of the society, except its primary founder Elizabeth McKenna who she told is “off island”. As she continues her research on the German occupation, she learns that Elizabeth was arrested for helping a slave boy and sent to a prison camp on the continent. She left behind a daughter, Kit, whose father was a German soldier. Juliet enlists help from Mark to uncover what happened to Elizabeth. Meanwhile her relationships with the members of the society deepens—specifically Dawsey. Just as Juliet and Dawsey are recognizing their mutual attraction, Mark shows up on the island with news of Elizabeth: she was killed in a prison camp. Dawsey tells Kit the news, and Juliet leaves the island with Mark.

- Ending Payoff — Juliet returns home, lower than ever and unable to write. She breaks off her engagement with Mark and is finally able to begin. She drafts her book on the Guernsey and the occupation, all the while missing her newfound family on Guernsey. She presents the completed book to Sidney but says he can’t publish it without the society’s permission. She tells him her intent to return to Guernsey “If they’ll have me”. Meanwhile she sent a copy of the book to them as well, and Dawsey reads between the lines of the letter that she is not getting married. He catches the first boat to London to find her. They meet up on the dock, both on their way to see the other, and Juliet asks him to marry her. They return to Guernsey and raise Kit together.

*Notes on the written version coming soon.

I’m a little squirrelly on the genres right now because I have the book and the film floating in my head and they are quite different, although I do adore both.

What seems most clear is Worldview-Education for Juliet, and a Love-Courtship for Juliet and Dawsey, as well as what feels like a Society story for Elizabeth McKenna and the people of Guernsey during the occupation.

The book gives more precedence to the Society story, whereas the film focuses more on the Love story. I appreciate both for different reasons, but they are quite different. There are several subplots that are stripped out for the film version (no surprise), and characters that are combined / shifted. If anyone is interested in writing an epistolary novel, I cannot recommend the book highly enough. I have a feeling you’ll hear that a few more times before the show is over.

Valerie: I think it’s a global worldview education story with a love story secondary genre.

Leslie: Because Juliet’s circumstances and goals change significantly by the end, I’m tempted to suggest Worldview-Maturation, but I’d definitely place the global story in the Worldview category.

Anne: I’ll be looking at specific characteristics of the novel that didn’t lend themselves to a filmed story, but I just want to confess that I avoided the book when it first came out because of its silly title. Yes, I judged a book by its cover. I decided that it wasn’t for me, because “whimsy” which the title seems to promise, is not something I’m drawn to in a story.

Boy was I wrong! Thank you, Kim, for proposing this story, because it has far more depth and substance than its title suggests, and I have rarely enjoyed a novel so much. I’ve got a nice first edition hardcover on order, and it’s about to grace my top bookshelf.

The Principle – Kim – How values are established in the beginning hook

When I first was listening to Shawn on the podcast back in 2016, well let’s just say I had absolutely no idea what he was talking about. He used words like Life Values and Polarity Shift and they went right over my head. I remember straining my ears and squinting my eyes as I listened, as if I could muscle my way to understanding my sheer will. Alas, no. But, after a lot of toiling, after a lot of wading through the dark, and more cognitive dissonance than I like to admit, Life Values are one of my most favorite story principles. They have become my primary lens for seeing stories.

I’ll do my best, today and throughout season six, to share some of the insights I’ve had about them, and how understanding them helps us craft better stories.

The way I see it, Life Values are a part of a bridge — the first step to communicating to what a story is really all about. Life Values represent the Universal Human Needs that we all have. They take the Human Need and make it one degree more specific. Then those Life Values get put into a story — a specific protagonist in a specific setting has a specific want / need and faces a specific conflict. And then that story plays out in time, from beginning to middle to end. And as each of those moments play out, they too have a beginning and middle and end. And so each moment in a story is communicating something to the reader. The more aware we are of what that something is, the more intentional we can be about how we choose to go about it.

And so, my purpose this season is to look at how Life Values are introduced and established at the beginning of a story. The devices that authors use to transmit the various underlying Life Values and meanings to their readers.

Beginnings are such an important part of a story—so many crucial tasks to be accomplished. They must hook our interest, introduce the initial conventions (characters, setting, means of turning the plot — in other words, the opportunity for conflict/change to occur, often as set ups for future payoff moments), they must establish life values of the status quo and signal genre(s) at play (content, reality, and so on).

Now, not all of these items will necessarily exist on the page prior to the inciting incident of the BH, but many of them will. All of this is just the beginning of the beginning hook. The rest will no doubt be introduced shortly thereafter across the remainder of the BH.

But by looking closely at this story moment—the status quo to inciting incident—not only can we discover how to craft strong openings to our stories, we will learn about the primary elements needed to make any life value shift its maximum impact. As I referred to it last week in our It’s a Wonderful Life episode, Life Value Shifts (aka Turning Points) have a Before / During / After.

And if you can track with me, I hope you’ll see that the inciting incident of the BH is a turning point of the first sequence of a story.

Okay, so that’s enough preamble. Let’s look closer at the beginning of The Guernsey Literary and Potato Peel Pie Society.

As I see it, the inciting incident of the BH in both the book and film is when Juliet receives Dawsey’s first letter. In it he tells her that he found her address in the font of a book by Charles Lamb. Then requests information for a bookshop so he can order another Charles Lamb book.

This signals a shift in Juliet — she feels a renewed sense of purpose, a specific problem to solve, and a puzzle/mystery to uncover. It provides a sense of inspiration that she’s been lacking. And learning of the hardships of others during the war, the German occupation on Guernsey that she didn’t know much about, helps her cope with her own post-war cognitive dissonance. Digging more deeply into true wartime experiences (the opposite of what she did in her Izzy Bickerstaff book) feels meaningful. So all of this will build over the course of the story, but it begins with Dawsey’s first letter.

So, knowing that Dawsey’s letter is our kick off to change, what then must come before? What information does the reader/viewer need to know in order for that moment to matter and stand out? Well, the opposite of course.

If Dawsey’s letter signals a Life Value Shift from meaninglessness to potential meaning (neg to pos), then we need to see what exactly is negative in Juliet’s life. And negative in this case is very specific. It’s “meaninglessness” — lack of significance, lack of purpose, hollow, empty.

Let’s see how the film clues us in to this truth for Juliet.

Valerie – Forces of Antagonism in the Middle Build

This week I’m continuing my study into Forces of Antagonism, in particular, what it means for the middle build to belong to the villain. The middle build is half the story, and it’s here that writers get lost and stories lose their way. Because of that, I want to understand how writers use Forces of Antagonism to develop the middle build. How do they keep a protagonist from getting her object of desire? How do they progressively complicate the story and raise the stakes? How do they force her to act and change?

Not surprisingly, the middle build begins when Juliet leaves her ordinary world of London and goes to the extraordinary world of Guernsey. The middle build ends when Juliet returns to London. So, it’s Juliet’s time on Guernsey that I’ll be concentrating on.

What does Juliet want and what does she need? She wants her life to have meaning (meaningful relationships and a meaningful career). On the surface, Juliet seems to have everything yet she watches a balloon floating away in freedom, with envy. To have the meaning she seeks, she needs to abandon material wealth in favour of deeper connection with people, but also with her art.

At the end of the beginning hook, Juliet thinks that everything is going wonderfully with her life. She’s a financially successful writer with a book tour planned, and she’s engaged to a wealthy diplomat who plans to take her away to New York for a life of luxury. She plans to be on Guernsey only for a weekend to meet Dawsey and the other members of the Literary and Potato Peel Pie Society. Her plan is to get information for an article she has to write for the London Times.

Let’s take a look at how the Forces of Antagonism in the middle build conspire to get Juliet to abandon a future of New York high society in favour of one with a pig farmer in Guernsey.

It’s tempting to point to the German army as the main villain of this story, but I think that’s too simplistic. It’s true that WWII created the situation that all characters find themselves in. But that’s the backstory that has created the ordinary world of this film. The main antagonist (for my money) is Elizabeth. Or more accurately, Elizabeth’s ghost. There are minor antagonists as well of course, notably Charlotte and Eddie, but they aren’t my focus right now.

I’m also not focusing on the love story here between Juliet and Dawsey because, if I discussed every antagonist in the story I’d be talking for a half hour! Needless to say, Mark serves as the third point in the love triangle and is therefore one of the antagonists for that storyline.

Now, back to the global story. The first little bit of the middle build is all about Juliet arriving on the island and meeting the members of the literary society, but very quickly Elizabeth’s ghost enters the story and incites Juliet to action. Rather than returning to London after the club meeting, she decides to stay on Guernsey to find out what happened because she now knows that Elizabeth isn’t merely “off-island” as Amelia had said.

So far, I’ve stated pretty obvious facts and plot points, but what we’ve got to do is look at how Elizabeth’s story is affecting Juliet’s. Remember, the screenwriter is trying to get Juliet from an affluent, though emotionally empty, life in London to a meaningful life as a pig farmer’s wife. Having Elizabeth as a ghost is an excellent way to do that because she becomes far more compelling to someone like Juliet than if she’d been on the island as flesh and blood.

Elizabeth is the opposite of Juliet because the antagonist, by nature, is the opposite of the protagonist.

For Juliet, books are lighthearted entertainment. There’s no substance to Izzy Bickerstaff’s work. He’s a facade masking Juliet’s true artistic ability and desire. By contrast, for Elizabeth, books are the way to save her life, and the lives of her friends. When stopped by German guards, she quickly taps into their interest in reading and desire for cultural association, and invents the literary club as the reason for them being out past curfew. Not only does it get them out of that one difficult moment, but it also gives them an opportunity to meet each week. This helps deal with their deep lonliness and isolation, and enables them to somehow survive the German occupation.

With the exception of Sidney, Juliet doesn’t have any meaningful relationships. By contrast, Elizabeth’s life is filled with them.

Juliet is rich, Elizabeth is poor.

Juliet hesitates to speak her mind, Elizabeth is fearless to the point of confronting German soldiers in broad daylight.

Elizabeth is her authentic self at all times. Juliet is never her authentic self.

We’re used to thinking of Forces of Antagonism as external villains who actively oppose the hero. Here we have an external antagonist who is passively prompting the protagonist into action (I say “passively” because Elizabeth exists as a memory after all). Elizabeth pokes Juliet’s internal shadow (that part of her that knows that life with Mark and writing as Izzy Bickerstaff is not quite right), and she highlights the societal antagonists (for example, class structure and opinions of the German soldiers).

Elizabeth’s ghost entices Juliet. It compels her to stay on the island, to ask questions, to do research and to expose truths. What’s more, as Juliet learns about Elizabeth (who she was and what she did), she begins to question her own decisions.

This sort of internal struggle shines in novels and other written stories. It’s harder to portray on a screen, so when we’re studying stories through film and television, we have to remember to look at the actors’ choices. Internal questioning might be portrayed through a gesture or the look on someone’s face.

The Guernsey Literary and Potato Peel Pie Society uses another neat device to visualize Juliet’s internal struggle, namely her engagement ring.

At the end of the beginning hook and beginning of the middle build, Juliet loves the ring. She wears it proudly and, even when she takes it off so as not to be conspicuous, she kisses it. The next time it appears is right before Juliet finds out about the occupation. She still seems pleased with the ring and all it implies, but she hides it from Eli. Then Elizabeth’s story begins.

When the ring resurfaces the third time, Juliet has learned the whole of Elizabeth’s story. She confesses her engagement to Isola but seems embarrassed by it all. When she says that Mark is an American, she grimaces. When asked why she isn’t wearing it, she makes up an excuse (she doesn’t know the answer to that question herself!)

The ring enters the story two more times; when Mark arrives on Guernsey and when Juliet returns it to him at the end of the film. Not surprisingly, both of these events coincide with Juliet’s discovery that her relationship with Dawsey is more meaningful than with Mark, and her realization that if she is to be her authentic self (as Elizabeth was), she can’t be a diplomat’s wife.

Let’s circle back to Elizabeth as the Force of Antagonism in the middle build. It’s Elizabeth who keeps Juliet on Guernsey. And Juliet needs to be on Guernsey (the extraordinary world) if she’s going to have the internal worldview shift.

Finding out why Elizabeth was arrested in 1944 is what makes Juliet question Dawsey, Amelia and Isola. Each new detail about Elizabeth and her adventures, makes Juliet question her own life and choices. Even though this is a global internal story, there still needs to be an external agent of change. Something has to be happening outside the protagonist to cause a shift within the protagonist.

This is very similar to what we saw last week with It’s A Wonderful Life, because after all, both stories are global Worldview > Education stories. Both George and Juliet are looking for meaning in their lives.

So, what does it mean for the middle build to belong to the villain? It means that, at every turn, the Force of Antagonism is challenging the protagonist and forcing her to act. Elizabeth’s ghost is challenging Juliet. It’s making her question her life decisions and her relationships. It’s forcing her dig deeper into Elizabeth’s life, her relationships and her disappearance because it’s only by observing just how meaningful Elizabeth’s life was, that Juliet can truly understand how meaningless her own life has become.

If you think of an external genre story, like an action movie, it’s easy to imagine the villain literally getting in the way of what the hero wants. The villain is an obstacle to be overcome. For example, in Die Hard, Hans Gruber is thwarting John McClane’s efforts to save the victims. Everything is happening in the external, physical world. Neither Hans nor McClane have profound internal shifts (or even not-so-profound internal shifts!).

Clearly, John McClane and Juliet Ashton are going through two totally different scenarios.

McClane’s story is external, Juliet’s is internal. McClane’s Force of Antagonism gets in his way and makes it more difficult for him to achieve his object of desire. However, in The Guernsey Literary and Potato Peel Pie Society, Juliet’s Force of Antagonism challenges her to change internally precisely so that she can achieve her object of desire.

And here we have yet another important reason to study masterworks. It’s so easy to get lost in the middle build, and one of the reasons is that we don’t understand the force of antagonism well enough. We haven’t studied stories like the one we want to tell, in order to understand how the antagonist controls the middle build. We can easily miss the fact that, in an internal genre story, the antagonist causes the protagonist to shift internally precisely so that she can get what she wants. By challenging the hero, the villain helps her achieve her objects of desire.

Anne: Mark is more clearly an antagonist in the novel—though I love Valerie’s assessment that the “ghost” of Elizabeth is the force of antagonism in the movie. Mark is much more clearly arrogant and unconcerned with Juliet as a writer and a person. He thinks nothing of her writing career. He sees her as an ornament, and is kind of a pleasant bully, bombarding her with endless flowers and telling her how much he can do for her, whether it’s what she wants or not.

All this time, we have no way of knowing Dawsey’s age. His letters are a bit old-fashioned and he gives an impression of being in late middle age. It isn’t until Juliet meets him that we understand that he’s only about 40, to her 32. There’s an attraction of spirits or minds between them, but the romantic attraction is left unexamined until Juliet has finally dispensed with Mark. The film makes the attraction to Dawsey her excuse for breaking off with Mark, but in the novel, she comes to the decision honorably and independently, because she recognizes the hollowness of their relationship.

Leslie – POV/Narrative Device

I’m studying POV and Narrative Device this season. You may have heard me say this before, and will probably hear it again … if genre is what your story is about, POV and narrative device are how you deliver the story to your reader. And while POV tells you whether your story is delivered via first person or third person, for example, and whether it’s written in past or present tense, the narrative device or situation tells you who is telling the story, to whom, when and where, in what form, and why. When we study the choices that other storytellers make, we learn how to make better choices ourselves—even when we choose to do it differently. Every story we read has lessons about the craft of writing and storytelling. It’s particularly useful to look at adaptations because we can see how two different creators present the same basic story.

The narrative device in The Guernsey Literary and Potato Peel Pie Society is easy to spot. It’s epistolary, a collection of written materials collected by some fictional entity or fictional situation. Here we have letters and telegrams to and from Juliet, Sydney (her publisher), Sophie (her friend and also Sydney’s sister), Mark (her suitor), as well as several people from Guernsey (Dawsey, Amelia, Eben, Adelaide Addison, and more).

The film isn’t epistolary. The story isn’t delivered through written elements, instead we occasionally see the letter’s recipient reading it, which isn’t very exciting most of the time, so we also see the events described in the letter dramatized with accompanying voiceover. The letters and other documents are additions to some scenes, they don’t comprise the scenes as in the novel. A true epistolary narrative device is hard to recreate in film because of the nature of the device.

Similarly, a spoken narrative device is difficult, though not impossible, to recreate in a novel. Several qualities of speech are missing, including changes in volume, emphasis, and tone. There are ways to translate these elements—we can imitate the word choice and syntax of speech, use punctuation and italics to support the feel of speech—but ultimately, it’s a translation of one form to another.

We can recreate a taste of the true form of the material in an alternate form, but the experience is a little different.

The POV of the film is typical for its medium and achieved with camera angles. There are distant establishing shots, mid-range shots that help us take in the scene, tight shots where we focus on what the characters are doing or their expressions to give us an idea of what they are thinking, and so on. The narrative device in the film is not as clear as in the novel. It feels like a non-specific, god-like omniscient narrative device.

I watched the film before I began reading the novel, which meant I could enjoy the film in its form without comparing it to the superior form. This story begs to be told in epistolary form. It works as a film, and it’s enjoyable for what it is, but the novel is a much better vehicle. More on why I think that’s the case in a moment because I want to mention what’s really useful about studying these two forms together.

Let’s forget that these are two different forms of media—for our purposes, we’ll consider them categories of narrative devices. If we think about them objectively as two vehicles that deliver a combination of events and characters, life value changes and controlling idea, we see that one delivers more emotional content and a greater sense of the micro and macro life value shifts that happen from the beginning to the end of the story. There are stark differences in the audience (though there may be significant crossover) and the amount of time it takes to consume the story, but there are other differences that matter, many of which Anne writes about below. If you understand these differences across the broad categories, you can use them to think about narrative device and POV within the categories.

Let’s talk about epistolary narrative devices generally …

Fun fact: Epistolary novels became popular as part of the postal culture of the 19th century. In other words, storytelling reflects social and cultural practices. Obviously films and TV have had an effect on novels as well.

Epistolary form can include letters, but also journals, diaries, newspaper articles, government records, and other written materials (an extreme example in written form is Ship of Theseus, which has several actual printed items [news articles, postcards, confidential documents, handwritten letters, and a map written on a napkin] tucked into the pages of a hardcover book that includes marginalia from two separate readers. A few other examples include Ella Minnow Pea, A Tale for the Time Being, The Martian, and The Color Purple. I would be remiss not to mention Dracula.

Epistolary novels create an interesting reader experience: They pull us out of the narrative, and the end of each letter is an opportunity to stop reading. But the feeling that we are eavesdropping is enticing, and we don’t get this in the film. The device appears to capture more details of real life, especially when the letters are personal. It changes the details we would naturally include and provides useful constraints for each scene. Of course, just because the form permits more real life doesn’t mean that you shouldn’t scrutinize the details included in the stories. The details may appear to be offhand, but in a story written this well, I’d bet they were closely scrutinized.

When you have multiple correspondents, as we have in this story, we get to see how characters relate to each other, what they reveal and what they withhold in different circumstances. It’s an exquisite form of dramatic irony. Multiple points of view give us clear constraints and goals. Each character involved has a want and need they are trying to achieve through writing.

In epistolary form, the who of the narrative device includes the creator of the written elements, but also the character who collectsand curates them, and that act should be motivated by specific reasons too.

In terms of POV, teh epistolary form can employ first or third person accounts (for example, letters and telegrams versus government records).

Something I’ve noticed, the more complex the story, the more complex the narrative device tends to be and the more thought you should give to your narrative device/POV, and of course, the more challenging the writing because you are purposefully pulling the reader out of the story. The film is a fairly simple story, but the novel is a much more complex one. Because the novel is well executed, it provides a richer experience.

My favorite part of the novel, is related to the reason Kim selected it. This story is about a writer finding her way professionally and personally in the wake of a devastating war. Within Juliet’s letters that unfold over the course of the novel, we see her finding her path and voice through her writing. The Life Value shifts are communicated in the way she writes about what she wants and needs. Her words and those of the people in her life deliver the combination of events, characters, and controlling idea, creating a deep emotional experience of change. Juliet is confused and wobbling in the beginning and clear and steady by the end—we experience all the context and rich details. The film, though it’s lovely, tells us about Juliet’s story, the novel allows us to experience it. In other words, the gift of writing for the writer is the process of putting down the words, not the product.

Anne – Novel to Film Adaptation, the “Hollywood Don’ts,” and what makes this literary novel better than the movie

In Season Five I was interested in why novels are so often better than the films adapted from them. I looked at three novel-to-film adaptations, and in two cases, I found the novel better than the film—deeper, more engaging, and more meaningful. (The third one was a draw.)

To find out why, I came across the seven qualities your novel should NOT have if you want it to read like a smooth, easy Hollywood movie. I called them the “Hollywood Don’ts,” and I’d like to go over them again.

These are the rules you should follow if you’re interested in writing a smooth novel that’s as easy to read as a Hollywood movie is to watch.

By contrast, these are some rules you should consider breaking if you’re aiming more towards the literary side.

Notice as I go through them that they don’t touch on most of the Editor’s Six Core Questions. I’ll address which aspects of Story Grid methodology they do touch on.

When I say a novel fails one of these criteria, it means I think the novel is actually better than the movie because it contains elements that are unique to novels; elements that don’t translate well to film, and which lend depth and meaning that the filmed version will tend to shear off.

1. Your novel will be under 300 pages or under 80,000 words, but over 15,000 words. Too long and a filmmaker would have to cut a lot of it. Too short, and they would have to make up stuff to fill in the time.

This Hollywood Don’t touches on what Shawn calls the “Time Genre” on his genre five-leaf clover, and tells us that a medium-length novel is the maximum size you should aim for.

- Guernsey Literary comes in at a slim 290 pages, and just over 72,000 words, so we can tick that box. What’s astonishing is that such a short novel manages to present such a complex web of vivid characters and their relationships, many (many!) of which the movie simply left out.

2. Your cinematic novel will be written in scenes, and will have the three-act structure of a beginning, a middle and an end, because that’s how movies are built, and that’s what readers of popular movie-like novels expect.

This Don’t touches on the Editor’s Six Core Questions number six: what is the beginning hook, middle build and ending payoff. Whatever form of story you’re writing, for whatever audience, you do need a beginning, middle, and end. But literary novels can fiddle around with conventions like chapters and scene breaks.

- Guernsey Literary is a series of letters, not divided into obvious scenes or chapters. It’s divided into a Part One and a Part Two, with the division at approximately the midpoint shift. In the novel, that midpoint is where Juliet finally goes to Guernsey. Part One ends with Mark denigrating her decision to go, and Part Two opens when she’s been there for a day.

The movie, as Valerie points out, has had to put a clear three-act structure on the story, with the location change happening at the beginning of the middle build rather than in the middle.

In the novel, this big shift of location represents Juliet’s turning away from Mark and towards this place and these people who are going to bring out her true gift. We see that a lot at the midpoint shift: the protagonist stops running and turns to fight. Here, she has run from Mark, but she’s also turning to face her inner antagonist: the indecision and writer’s block that have been making her unhappy throughout the first half.

3. Your text will ideally not depend on your authorial voice or style to deliver its message, or on tone such as sarcasm or irony. That kind of strictly literary, textual stuff doesn’t translate to the screen.

This Hollywood Don’t points to the Style genre of the five leaf genre clover.

- Guernsey Literary is a riot of voices, though not so much authorial voice as idiosyncratic character voices, revealed in the letters. The character voices gave the actors in the film a lot to work with—too much, apparently, since the film cuts half of the characters.

I think the novel fails this criterion. It is strictly literary and textual.

4. Your novel won’t lean heavily on literary allusions, philosophical ideas, or abstract meditations. None of that is story per se, and it’s unfilmable.

As with Hollywood Don’t number 3, this one points to the Style genre as well.

- Guernsey Literary is rich with extracts from literature, since, after all, the characters are members of an avid and longstanding book group. I would classify these little readings as grace notes in the text, revealing character and adding a lot of humor. The film does nod to them—we witness a couple of readings—but we don’t get the full effect of the joy these beleaguered islanders derive from reading and rereading the few books they could lay their hands on.

The novel fails this criterion.

5. Symbolism, if any, will not lie at the heart of your story. Many great movies are rife with symbolism, provided it’s visual, but symbolism is lost on general audiences. If stripping it out would break your story, you’re not writing cinematically.

Along with Hollywood Don’ts 3 and 4, number 5 here points to the Style leaf.

- Guernsey Literary isn’t rife with symbolism. Its meaning is clearly set out in words.

It gets a checkmark here.

6. Your cinematic novel should not be written in the first person, or use a complex combination of points of view. The only way to work with that in film is the dreaded voiceover.

Here we address one of the big Editor’s Six Core Questions, “What is the Point of View and Narrative Device?” It’s a big one, so big that Leslie is spending the entire season on it.

- And oh boy howdy does Guernsey Literary violate this one. Every single character except the absent Elizabeth and a couple of children too young to be letter-writers has a first person point of view by virtue of writing a letter. You simply can’t ignore letter-writing in this story. The film does its best with shots of handwriting and fountain pens. Then it does its worst with a lot of voiceover reading the contents of a letter. There are even a couple of awkward spots where Juliet, all by herself, begins reading a letter out loud before the voiceover fades in.

The thing is, letters—writing, sending, receiving and reading them—is at the very heart of this story. They aren’t incidental, and they aren’t mere devices to push the story forward in selected places. The novel is 100% letters—well, and telegrams, cables, “night letters” and notes shoved under doors. It’s about people who love to read and love to write, in a time when telephones weren’t in every house. The passage of time is marked with letter headings. Character is revealed in these distinct voices. With the best will in the world, the filmmakers couldn’t simply strip away the letters and tell the story without them. But they tried.

Honestly, I don’t think I’ve ever read a novel that was a better candidate for a multi-voiced audiobook—which the audiobook is, and it’s wonderful.

The novel utterly fails this criterion.

7. And finally, your novel will not depend on detailed historical information to work. Apparently, movies that lay on too much historical realism tend to lose sight of the story.

This final Don’t points to the Reality leaf of the genre clover, where Historical fiction is embedded under “Realism,” and it just says beware of writing something that’s “too historical.” Whatever that means.

Honestly, I’d think “too futuristic” or “too fantastical” would be an equal bar to filming, but there appears to be no limit to CGI budgets to help moviegoers understand those unfamiliar worlds.

- This novel, conceived in the 90s and completed in 2008, is looking back 50 or 60 years to World War II. The novel has plenty of time to describe both the realities of a wartime occupation, and people’s feelings about it—in fact, I learned a lot about the second world war reading it.

The film is forced to distill a lot of that historical detail into easy-to-grasp visuals of German soldiers, starving forced laborers, and hungry locals. It did a fine job: costumes, settings, props and the on-location filming are beautiful and convey quite a lot of historical war information clearly. But it couldn’t go into the depth that the novel does.

I’ll give the novel half a checkmark here.

Let me end by saying again that writing a smooth-reading, fast-paced novel that would make a great movie is a laudable goal. If it’s your goal, you’ve got these seven guidelines to help you achieve it. If your novel gets made into a movie, it’ll probably be a better movie than the filmed version of the Guernsey Literary and Potato Peel Pie Society.

But if you do lean to the literary side, as I like to think I do, then this Hollywood Don’ts list might give you some real insights into which rules to break. And the Story Grid, particularly the Foolscap questions about narrative device and point of view, will still be your friend.

Final Thoughts and Takeaways for Writers

Here are a few key takeaways for writers who want to level up their own writing craft.

Kim: When crafting your story’s opening, identify your first moment of change — the inciting incident of the beginning hook. Decide based on your genre what change will take place there–the global life value shift, and polarity shift. And then set out to establish the opposite–decide what information is essential to deliver to the reader before this moment, and then how you want to deliver it. And then also, demonstrate the after effect, how this shift carries the story forward. And remember that these decisions are a starting point — your hypothesis that you will test when you draft. It might not work, and so you will you revise and try again.

Valerie: For me, the key takeaway is that the Force of Antagonism looks very different in a global internal story than it does in a global external story. Unless we study masterworks, we can easily miss the fact that, in an internal genre story, the antagonist causes the protagonist to shift internally precisely so that she can get what she wants. By challenging the hero, the villain helps her achieve her objects of desire.

Leslie: We’re all emphasizing the importance of reading and studying masterworks, and specifically, I encourage you to look closely at the decisions writers make. We can’t know exactly what’s in the mind of the writer, but spending time considering how the choices work, what the consequences are, and possible reasons for the choices is valuable exercise that will help us become better writers.

Anne: When you’re thinking about how to expand your reading horizons in order to become a better writer, try a novel or two outside your comfort zone, one that you’re sure isn’t “for you,” as I was sure Guernsey Literary wasn’t for me. I’ve learned more about style and voice from leaving my ordinary reading world than I ever could have staying within my comfy little familiar reading space.

Listener Question

To wind up the episode, we take questions from our listeners. This week’s question comes to us from Rhoadey on Twitter. Rhoadey writes:

Hi, @AnneHawley! I’ve got a quick @StoryGrid related question: is the “crisis” of each act presented in its own scene? Or is it implied by the turning point?

Anne: Hi Rhoadey, and thanks for the question. This one comes up from time to time, and there can be some confusion around it because the Crisis is one of the Five Commandments of Story, so the Crisis of each act must have its own scene, right?

Well, no. Not really. There must be a crisis—don’t get me wrong—but it can be, and often is, implied. Even when it’s laid out on the page, it rarely takes up a whole scene.

Here’s the simplest possible version of a story to illustrate the point:

You’ve been invited to start down a path towards something you want. Pretty soon there is a small obstacle. You overcome it. A bit farther on, there’s a bigger obstacle. You keep going because you still want what you want, and it’s over there. Then you come to a fork in the road. Neither branch is heading over there. One branch goes left and one branch goes right. You can’t see far down either road, and you have to choose. So you pick one, and continue on your journey.

You’ll recognize the invitation as the Inciting Incident. The obstacles are Progressive Complications. Discovering the fork in the road is the final complication, aka the Turning Point Progressive Complication (or just, the Turning Point). Choosing a road is the Climax, and continuing on your journey is the Resolution.

So where’s the Crisis? The crisis in this little story is the question of which path to choose. In this little story, it falls silently after you come to the Turning Point and before you make your Climactic choice.

What goes on in that crisis question is often wholly internal to the character. In a well-constructed story, the calculation the character makes to reach a decision should already be clearly implied by what’s gone earlier.

In my simplified example, the reader probably doesn’t want or need to see every pro-and-con decision-making thought that went through your mind. That’s why the crisis is often more subtext than text. It’s implied by the turning point that precedes it and the climactic decision that follows it.

I pulled The Hunger Games off my shelf and flipped to about the three-quarter mark, where I’d expect to find the big global turning point, crisis, and climax. On page 310 in the trade paperback edition, Katniss wakes up in the arena on her 14th day, and mentally weighs the pros and cons of winning with or without Peeta. Her decision to stick with Peeta is based on considerations that she shares through her thoughts right on the page.

For your own writing, a mix of crisis moments in text and crisis moments in subtext is probably a good plan, but when it comes to the global crisis, your choice really must be solidly grounded in previous setups. That way, if the crisis question is only implied, the reader can easily infer how the character reached their decision. And if it’s on the page, there should be no decision-making information that the reader hasn’t encountered earlier in the text.

I hope this helps. And remember, you can do this same kind of research, and I encourage you and everyone to give it a shot. Flip through a favorite novel and try to spot the crisis in a few scenes. It’s good practice.

If you have a question about any story principle, you can ask it on Twitter @storygridRT, or better still, click here and leave a voice message.

Join us next time when Valerie will look at Forces of Antagonism in the award-winning 2014 Performance story film, Whiplash. Why not give it a look during the week, and follow along with us?

Your Roundtable Story Grid Editors are Valerie Francis, Anne Hawley, Kim Kessler, and Leslie Watts.