This week, Leslie pitched Deep Impact as part of her Season 5 look at action stories on with an epic scope. This film, which came out a couple of months earlier in 1998 than that other blockbuster about giant space rocks hitting the earth, was directed by Mimi Leder from a screenplay by Bruce Joel Rubin and Michael Tolkin. (The other one was Armageddon, in case you’re wondering.)

The Story

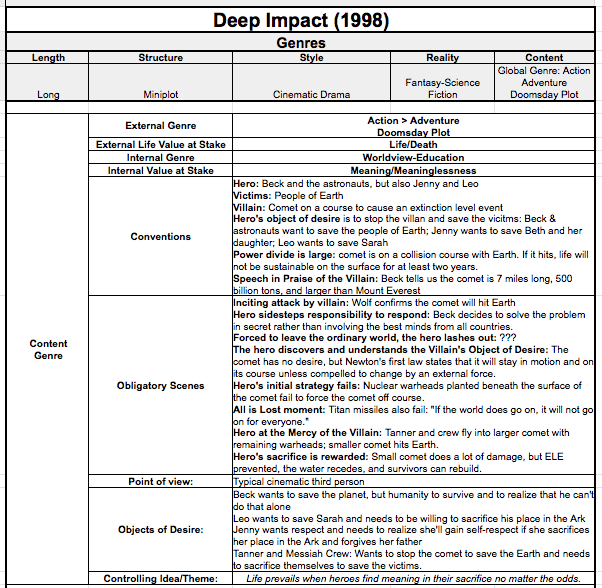

External: Action-Adventure, Doomsday Plot

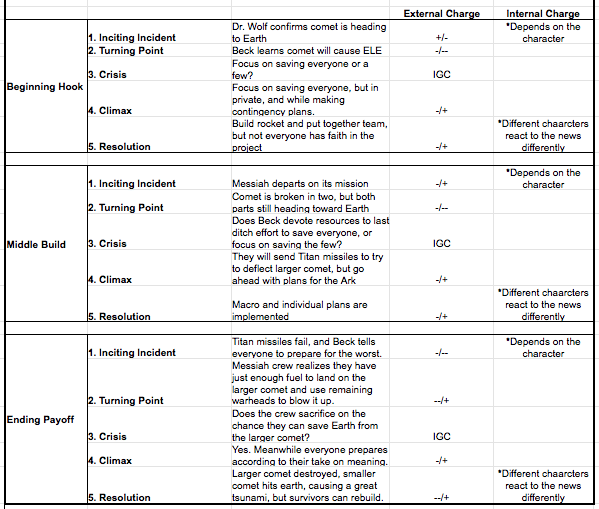

- Beginning Hook – Leo and Sarah discover a comet that Dr. Wolf determines is heading toward Earth, but when President Beck learns that the comet will cause an extinction level event, he must decide, do we focus our efforts on saving everyone or the chosen few (offscreen). He decides to attempt to save everyone and works in secret with the Russian government to divert the comet and is forced to reveal this when Jenny Lerner stumbles upon the story.

- Middle Build – The Messiah departs on its mission and after a series of setbacks the warheads are planted within the comet, but when the explosion breaks the comet in two chunks, both of which are still heading toward Earth, Beck must decide whether to devote resources to a last-ditch effort to divert the comets with Titan missiles or focus exclusively on getting the people selected for preservation to the Ark. They decide to try the missiles but also move ahead with plans to move selected people to the Ark.

- Ending Payoff – The Titan missiles fail to change the course of the comet, and the plan to save one million people is put into effect in the US, but when the crew of the Messiah realizes they might have time to destroy the bigger comet, they must decide whether to sacrifice their lives on the chance they can prevent the large comet from hitting the Earth or continue back to Earth. They make the sacrifice, which eliminates the extinction level threat, saving humanity so they can rebuild.

Internal: Worldview-Education Miniplot

At each of the act-level climax moments, once President Beck and the others in power decide what to do about the global threat, individuals must decide how they will respond to the news and the revelations that follow. We see images, beats, and scenes of how different people in different levels of society react. These events are best understood within the context of the Worldview-Education genre. Here is the genre’s cause-and-effect statement derived from Norman Friedman’s “Forms of the Plot”:

When a sympathetic protagonist, with a naive or cynical outlook, experiences an opportunity or challenge that enlightens them to a broader understanding, they find new meaning in their existing actions.

I’ll follow the stories of three of the main characters: Jenny, Leo, and Tanner.

Beginning Hook

- Jenny Lerner: When she discovers that the president was hiding news of an extinction level event (before the rest of the country), she must decide how to manage the rift with her father. She joins him for a prearranged dinner with his new wife, but Jenny drinks heavily and is rude to them both. She won’t accept their gift of expensive earrings. During the press conference, she asks hard questions about if there are doubts about whether the Messiah mission will be successful.

- Leo: When he learns that what he spotted is a comet on a course for Earth, Leo must decide what this means to him. Instead of being afraid of the comet and the potential destruction of life on earth, he’s excited about having made the discovery.

- Tanner: When the news of the comet is revealed to the country and the rest of the world, Tanner is reluctant to leave his two sons, but is willing to do his duty. He’s aware that the younger members of the crew resent his presence and don’t believe he has much to offer.

Middle Build

- Tanner: Once the mission fails and the Messiah loses contact with Houston, Tanner and the crew must decide whether or not to head back to earth. Though there is a risk that they won’t survive re-entry, they turn around, hoping to beat the comets to Earth (the implication being that they have a chance of seeing their families again).

- Jenny Lerner: When Jenny learns that the mission has failed she learns that she has been chosen for the Ark but her mother won’t be because of her age, she must decide how to respond. Her mother convinces Jenny that she should take her spot: her mother is at peace and people will need Jenny’s voice and presence for continuity.

- Leo: When Leo learns that he and his family have been selected for the Ark and that Sarah’s family hasn’t, he proposes to her, so that she and her family will be saved.

Ending Payoff

- Tanner: After the Titan missiles fail, Tanner and the crew must decide whether to sacrifice their lives for the possibility of saving the earth from the larger of the two comets. They decide to make the sacrifice and all but Tanner are given the opportunity to say goodbye to their families before their final approach toward the comet.

- Leo: When he arrives at the Ark and realizes he will not be able to arrange to get Sarah once he’s inside, he goes back for Sarah, and together they take her baby sibling to high ground to escape the tsunami.

- Jenny Lerner: After the Titan missiles fail and she realizes Beth and her daughter are unable to escape the huge wave, she gives up her seat on the helicopter and goes to the coast to reconcile with her father.

Scroll to the end of the show notes to find the Foolscap Global Story Grid.

Anne: I was both bored and annoyed by the first half of this movie, though I’ll admit that by the second half I became more engaged as the ticking clock counted down to extinction of life on earth. I know Leslie has a lot to say about how an action story with an epic scope and a doomsday plot could be so scattered, so, Leslie, grace us with your insights.

Action Stories with an Epic Scope – Leslie

I’ll do my best. My goal this season is to look at Action stories with an epic scale because if you want to write a story this complex with lots of moving parts, it’s useful to study the ones that meet your criteria. Last time I looked at Thor: Ragnarok, an episode in a much larger story universe with a large cast of characters, existential threats, and a wide landscape.

For this episode, I pitched Deep Impact, a stand-alone story that includes a large cast of characters dealing with an existential threat on a wide landscape. As a story, Deep Impact doesn’t work as well as Thor: Ragnarok, but it serves as a cautionary example, showing us the pitfalls we face when we want to tell a complex story.

Deep Impact sells itself as an Action story, but key events about dealing with the threat happen offstage. That can mean that the story is muddled or that there’s more going on here than a straight Action story about the strategies heroes use to defeat villains—or both.

The Beginning Hook shows us how ordinary people from multiple levels of society are left out of the decisions about threats that affect them. Notice how the president’s aid so casually suggests that they hold Lerner to keep her from revealing what she knows and the president says, “It might seem that we have each other over the same barrel, Ms. Lerner, but it just seems that way.” Everything about that scene suggests that Lerner has no power. And I suspect this was the real point of the story: What do ordinary people do in the face of existential threats? That’s a very interesting approach to take, and you can include several different ideas within one story, but it’s vital to focus on one primary storyline.

This story was released within two months of Armageddon, another disaster film that features a large object—an asteroid in that case—hurtling toward Earth. We follow the team of heroes almost exclusively. Like Thor: Ragnarok, Armageddon is primarily about two levels of conflict: (1) the heroes against the villain and (2) the typical interpersonal conflicts that arise among the heroes when they try to defeat the villain.

Hat tip to my Action Genre study group for helping me understand what’s happening here generally and to Story Grid certified editor Melanie Nauman specifically for the clue that the title has two meanings: the comet has a deep impact on the people, but the people have a deep impact in how they show up in a crisis.

Deep Impact should be a great film. It explores societal conflict, which is important because not all solutions work equally for all levels of society, but also internal conflict, because how we see a problem and where we sit in relation to the people in power changes what we do. Also, members of the media have to decide what is appropriate to reveal and when, and individuals have to cope with daily life and its challenges in the backdrop of a crisis that might end the world. These are big and important questions in the twenty-first century.

So the execution of the ideas here isn’t great, but studying stories that don’t quite work can be very instructive. In particular, I want to look at some of the pitfalls that may arise when we attempt to write a story like this. Understanding these problems will help us avoid them.

Pitfalls

Global Story Spine

On the surface, this story is about an existential threat. It’s an Action story, but as I mentioned, it’s also about how individuals rise to the challenge and express their gifts. The tagline on the film poster is, “Oceans rise, cities fall, hope survives.”

But neither storyline really works. As I said a moment ago, in the Beginning Hook and Middle Build, the main conflict about what to do about the threat happens offstage. We learn about the President’s decisions in press conferences. That suggests the story is about how ordinary people deal with this kind of threat, especially when they don’t have the power to make decisions regarding the macro plan. But this aspect of the story isn’t well developed and, as Valerie will explain in a moment, it’s hard to empathize with the characters.

There is some real potential with the ingredients of this story to write something complex that works, but if you want to make sure your story works, pick what your story is about, set up the 15 key scenes, the global story spine, to tell that story well, and then add the subordinate plots.

Plot Holes

This is not a hard science fiction story that relies on factual accuracy and logic. We’re not in the territory of The Martian, so we shouldn’t judge it by that standard. Even by a less rigorous standard, the film requires some hefty suspension of disbelief. There are plenty of problematic elements that pulled me out of the story.

Amateur astronomers do find new objects in the sky, and occasionally score significant finds, but it seems like a stretch that a comet so close wasn’t found by one of the many professional or academic observatories around the world. And for that matter, it seems quite odd that no one else in the world spotted this between when Leo and Sarah spot it and President Beck announced it to the world.

But the plot hole that’s big enough to drive a truck through involves the demise of Dr. Wolf. A collision with a semi turns Wolf’s vehicle into a fiery ball tumbling down the side of a mountain. But somehow news of the comet—with the name Wolf-Biederman attached—makes its way to the proper authorities. How did that happen?

Disaster films often include cheesy moments and plot holes, or scenes when the audience members think, “Yeah, right.” In a way, that’s part of the fun of these stories, and provides relief from the tension caused by the doom the characters face. You can get away with those moments when the global story spine is solid and when narrative drive pulls the reader into the next story moment right away.

The Big Meta Why

Execution aside, stories like Deep Impact matter because they provide examples of individuals who step up, do the right thing, and make personal sacrifices for the good of others, even if they aren’t involved in the macro decisions to resolve the major conflict in the story. There’s a wide spectrum here. You can write

- Action stories with no internal genre,

- Action stories with an internal genre for the hero(es), or

- Action stories that focus on how people make sense of the external threat and what they decide to do about it.

But you must make a choice if you want the best shot at writing a story that works. What do you want to dramatize? What’s your primary message?

Compare the clarity of Thor: Ragnarok to what’s happening here. Again, both of these stories deal with existential threats. The vast majority of the people at risk (in other words, the victims), can do little to impact their fate. The power divide between the heroes and the villains is large, but the power divide between the victims and villain is, well, astronomical. The heroes, Thor, Valkyrie, Banner, Heimdall, even Loki make decisions on behalf of the Asgardians. The point of view follows the heroes with occasional shots of frightened and disempowered citizens. That’s one way to present a story of existential threat. And that’s what the filmmakers did in that case.

But another way is to focus on ordinary citizens. We could shine a light on individuals and how they see what’s happening, what it means to them, and what they consequently do about it. This might seem like a small matter, but as Malcolm Gladwell showed us in The Tipping Point, “little changes have big effects” and that “epidemics [whether we’re talking about diseases or ideas] can rise or fall in one dramatic moment.”

This reminds me of Steven Pressfield’s novel about the Battle of Thermopylae, Gates of Fire. The Spartans face a huge army coming to wipe them out; imminent death was certain. Individual Spartans, both leaders and common soldiers, speak up about how they should approach the threat. Individually and collectively they decided that the way to face was to make their deaths mean something. By framing the situation in this way, they fought fiercely and bought time for the other Greek cities to mount a defense. That was the macro level. On the micro level, they focused on keeping their fellow soldiers alive. This story fits squarely within the War genre, not action, but you see how Gates of Fire and Deep Impact both show us the story from different levels of society. Pressfield nails the global War story in Gates of Fire, which means that it can support these deeper questions.

Which brings me back to the key takeaway here: get clear about the story you want to write. There are so many decisions you have to make: content genre, point of view, style, sales category. Take the time to be sure these practical decisions align with and support the story you want to tell.

Other Perspectives

Anne – Miniplot Structure

I am so glad you were on the case, Leslie, because I wasn’t able to be. Your usual level of clarity on the fundamental ins and outs of what makes a story either work or pop springs out all over the place is a goldmine for writers of any genre. The show notes are a rich resource, too.

Before we move on to Jarie and the love story subplot, I just want to say a couple of words about the mini-plot structure. Our basic Story Grid guidelines state that an Action story is always an arch-plot with a single main protagonist, and here we have three mini-plots:

- Jenny the reporter and her family and work story;

- Leo Biederman and his love story;

- Spurgeon the old astronaut and his team of young space cowboys, and

The President and his team don’t really constitute a mini plot–as Leslie has pointed out, most of his story happens off-screen.

Everyone was more or less heroic or brave or self-sacrificing, but no one hero led them all. The astronauts literally sacrificed their lives to save all humankind–all life on earth–and yet the story doesn’t revolve around them. Remember that other giant space rock hitting earth story I mentioned? Armageddon? It had far greater–dare I say it?–impact that year because it was absolutely clear who we were rooting for.

On the other hand, as Valerie’s going to cover, this attempt to make a mini-plot disaster story into an epic Action story did give me more time to feel a wider range of emotions, watching such a variety of characters face their doom. There was pathos and sorrow, and a win-but-lose ending that was in some ways more satisfying than the absolute win you get in more typical action stories.

I’m going to pass the mic to Jarie now, who’s got a few things to tell us about the love story subplot.

Jarie – Puppy Love Gets Serious for an ELE

Before I dive into love today, I just wanted to bring up the awesome amount of technology in this movie. POP Mail Servers, dial-up modems, 3.5” floppy disks, in car cell phones, and my favorite, Jolt Cola. I miss the 90’s just enough to be happy that social media did not capture all the pegged pants, wave haircuts, and Bartles & Jaymes wine coolers, that some of us might have indulged in.

Even better, is the 2 drink minimum lunch between mother Robin & daughter Jenny where Robin tells her dear sweet daughter, as she sips a martini and smokes a cigarette, that she now has a stepmother that’s two years older than her. Classic late 90’s Complain About Your Life Over Lunch scene.

Among this most spectacular backdrop of all things 90’s, we have the budding love between Leo and Sarah. This love sub-plot does not show up in earnest until after the midpoint shift, which is when the Messiah fails its mission. The clip starts at 1:10:55 – 1:11:30. It’s Leo offering to marry Sarah more out of generous-but-naive heroism than out of love.

This confession of love scene does not work for me at all. Frankly, I think it’s because I don’t believe in the love between Leo and Sarah. It’s not been developed enough. Maybe I could believe Puppy love but not “let’s get married.”

The montage that follows this scene, at ~1:12:00 and ends at 1:13:51, includes Leo and Sarah getting married amongst the chaos, carinage, reflection, and preparation for the end that is too come. Frankly, I didn’t work for me but it did accelerate the love story to marriage in a couple of minutes.

The “lovers” break up scene or rather are separated scene is unsatisfying since Leo leaves with his family and abandons Sarah. Equally odd is when he goes back for her on his bicycle. Then, the lovers reunite scene when Leo drives the motorcycle through the traffic jam. The tearful scene when they take the baby and go to high ground. Poorly done because it’s not believable.

Valerie: I see where you’re coming from, Jarie. I just wanted to point out that this particular moment is one of the few that generates empathy (and I’ll talk more about that in a minute). But here, we’re focused on the mom desperately handing one child over to another hoping that both may survive. In a scene is supposed to be about Leo and Sarah, our attention is drawn toward the crisis of a minor character.

Jarie: So true Valerie. I don’t really feel the love between them and it’s a little late for Leo to go back to his “true love.” I wanted to feel for Leo and Sarah. The obligatory scenes and conventions are present but weak. As an example, the lovers triangle is done right up from with Sarah going to something with another boy before we even know that Leo and Sarah are a thing. Maybe we’re just supposed to assume that.

This is a good example of even if you follow the “rules”, your love sub-plot can fall flat if not properly developed or rooted in reality. I don’t think it would have taken much more to give us that. For example, the lovers breakup scene could have been done earlier or been more dramatic like putting them on different buses and having one breakdown — anything else than what they did.

There is some redeeming love in this movie and it’s paternal between Jason and Jenny. Probably the most touching scene, for me anyway, is when Jenny comes back to tell her father she loves him. The scene is at 1:41:52 — 1:43:00. Jenny visits her father at the beach to be with him. They both confess to each other past transgression and that they missed each other.

JENNY: When I was 11, I took $32 from your wallet

JASON: When you were a baby … I once dropped you on your head.

JENNY: When you came to the studio and brought those pictures, I lied when I said I didn’t remember. I remember everything. I remember that we were right over there, and that’s when mom got that picture of the house. It was a perfect, happy day. I cam down here to let you know that.

JASON: Thank You.

JENNY: I’ve missed you since then.

JASON: I missed you, too

I think this beat is a good one to study in terms of the reconciliation between a father and a daughter before their demise. It has the right amount of humor in it as well and then a massive wave crushes them both as Jenny says “daddy.”

The real tear jerker (I cried) is The Heroes Say Farewell scene, which seems to be a trope for these kind of movies. It’s between 1:47:05 — 1:48:30 in the movie where some of the crew of the Messiah say goodbye to their families before they go on their suicide mission to explode the Wolf comet.

This could have been an even better scene but the cuts back and forth between the people running for their lives and the touching moments gives it a lack of continuity that’s distracting. For the Farewells, it ruins the narrative drive but the tension is still there as we build to the climax.

I think what writers can learn from this movie, in terms of love sub-plots, is that if you’re going to put puppy love turns serious in a movie like this, make it a little more believable. Add something to make the viewer or reader care a little bit. I don’t really care if Leo and Sarah make it.

The other love stories are better but still, there seems to be too many to keep track of. If you’re going to do this in a novel, I’d suggest sticking to a couple and fleshing them out so we as the reader connect with the characters.

Valerie – Creating Empathy

As I’ve mentioned in the last couple of episodes, empathy for the protagonist is essential. If the reader doesn’t relate to the hero on some level, then she won’t engage with the story; she won’t care whether the hero gets what he wants and needs. In a mini-plot story like Deep Impact, that means connecting to the protagonist of each storyline.

For writers, creating this is no small task!

Shawn explained that we can create empathy by following the heroic journey on the macro level and by clearly articulating the objects of desire on the micro level. As I continue to study into this a little deeper, I’m discovering that a number of other storytelling experts have suggested the same thing, although they talk about it in slightly different terms.

For example, John Truby says that getting an audience to care about a character comes down to “the fundamental weakness of the character and the character’s goal in the story.” He goes on to say that the weakness is the need of the character, “in other words what is that personal problem inside that is hurting the hero in such a fundamental way that it’s ruining their life. It’s very deep. And the entire story is going to play out the solving of that problem. The way they’re going to solve that problem is by going after a particular goal. They don’t know at the beginning that by going after this goal they will eventually deal with their great internal weakness, but if it’s a good story that’s exactly how it will work.”

In other words, Truby is talking about defining the characters objects of desire.

Last week I mentioned that Robert McKee suggests we identify a core of goodness in the character; that is, his humanity (which is another way of talking about the subconscious need).

I haven’t had a chance to work my way through all the Masterclass classes yet but I know that David Baldacci, Neil Gaiman, Judy Blume, Aaron Sorkin and Margaret Atwood all touch on this same point. We don’t care about a character because of how she looks or what she wears. We care about her because of who she is, deep down.

Ok, so this brings me to Deep Impact. Except for a couple of small moments in the film, I had trouble empathizing with any of the characters. I had very little emotional connection to any of the storylines and I think there are a few reasons for this.

First, we have to acknowledge that empathy is a subjective thing. I can empathize with a character that someone else can’t relate to at all. That’s perfectly fine. But, I think there’s more to it than that, and I have a couple of ideas as to where Deep Impact may have missed opportunities to generate empathy.

Let’s look at the recommendations we have from the pros so far. We can rule out the heroic journey for help with empathy on the macro level because this story is a mini-plot. That means the filmmakers really have to nail the objects of desire for each of the main characters we follow—and unfortunately they don’t. Here are a couple of examples:

Leo:

- Wants a relationship with Sarah

- Needs to put Sarah ahead of himself? (I guess)

Leo’s want is obvious, but his need is less so. I’m not sure how running back to get Sarah articulates his need. The chance of him finding her is slim, and he still can’t save the family, so it’s a repeat of what we saw earlier.

Jenny:

- Wants to move up the corporate ladder

- Needs to forgive her father

She gets both objects of desire, but one has nothing to do with the other and objects of desire are linked. Truby mentioned that in the quote I read above and Shawn goes into it in greater detail in The Story Grid: What Good Editors Know.

The President:

- Wants to protect the people of America

- Needs?

I don’t think the President has much of a subconscious need, which means there isn’t much of an internal arc. This leads me to an interesting question: is it possible to create empathy for a protagonist that doesn’t arc? I think the answer is yes—I mean, so many people root for James Bond, right? But I don’t know for sure. I’d have to study a bunch of examples and look for common patterns to figure out the answer, but for now, I’ve discovered a new question and a new avenue to investigate.

The crew of the Messiah:

- Want to destroy the comet to save earth

- Need to be completely selfless

The crew’s wants and needs (as a group) are clearly defined. It’s by realizing the subconscious need that they get their conscious want.

So, clearly there’s a problem with how the objects of desire have been articulated. But, there’s more to Deep Impact’s troubles.

Leslie has already alluded to the many plot holes, and boy, there are a lot! Suspension of disbelief is one thing, but insulting the reader’s intelligence is another thing altogether. There were several times in the beginning hook when I thought, “oh, you’ve got to be kidding me”. (Never before has a rookie journalist broken a story of such global importance so easily. Never before has the leader of a country so quickly given up secrets. The President assumed Jenny had the full scoop. She didn’t. But, she found it out on the internet?!?) I very quickly had to just accept that this script is held together with a bit of Scotch Tape.

I bring this up not to be unduly harsh or critical, but to highlight the fact that as storytellers, what we’re doing is creating an illusion. All the tools in our writer’s toolbox exist to help us develop that illusion and anything that breaks the spell and brings the reader out of the imaginary world, is a problem.

Large, persistent plot holes will destroy the illusion.

Then, there’s the sheer scope of the film. I suspect that the story is simply too big for the 2 hour format – this is exactly the problem we saw with Jupiter Ascending. There isn’t enough time to follow all these people who are dealing with massive issues.

The whole premise of the film is hard to relate to, to be honest. I’ve never had to consider what I would do in the event of Armageddon. I simply can’t relate to that particular problem and I think that it’s a mistake to try to get a reader to tackle this kind of issue on any real level. What I believe works best is to have the reader connect with the crisis of each individual story within this world. Extinction of the planet is the premise, but that’s not the issues the characters are dealing with; not really. Leo is dealing with the loss of his beloved. Jenny has abandonment issues. The President is, ironically, powerless to help the people he’s sworn to protect, and the crew of The Messiah must sacrifice themselves for the greater good. Those are the points that an audience can connect to. Unfortunately, none of them has time to fully develop.

As Jarie said, it’s hard to view Leo and Sarah’s love story as anything more than a high school crush. Sure, I can understand the reason behind the marriage, but the whole thing falls flat.

Jenny is entirely focused on her want, so much so that when she gives up her seat on the helicopter and goes to be with her father, it doesn’t quite ring true. Taking the child and getting on the helicopter herself seemed perfectly in character though.

The President … does he do anything more than move the plot along? He’s a herald more than a character with his own storyline. Once he delivers the catastrophic news, he walks off stage (presumably to his own protective bunker). He effectively abandons the people he’s supposed to protect. Either he’s completely cold-hearted (which I don’t think is the case or intention) or he’s got to somehow find a way to continue leading the people while dealing with his feelings of failure. The whole story could easily have focused on this one character dealing with this one need.

Of all the storylines, I connected most with the crew of the Messiah. It wasn’t until I articulated the objects of desire that I began to see why. Funny that Leslie brought up The Martian, because that’s exactly the story that was running through my mind when I watched these sequences. But, the audience didn’t get a chance to see the relationship between the crew members fully develop and that destroyed any chance for empathy to take hold as it could have—the potential was there though. When Gus Partenza was lost, I admit that I had to pause the movie to check to see which character he was. The crew didn’t spend any more time thinking about him than I did.

The friendship between Fish and Oren definitely had the most emotional impact, but I think that was due to Robert Duvall’s performance rather than the writing. And as novelists, all we have is the written word.

As I was watching Deep Impact, I kept thinking about Love, Actually which we studied in Season 4. Love, Actually has multiple storylines but the objects of desire for each character are clearly developed and as a result, the audience is emotionally engaged with each and every one. I can’t even think about Emma Thompson’s bedroom scene without tearing up.

Anne: Love, Actually was full of good things, wasn’t it?

As to those huge existential questions that are hard for individuals to relate to? I live on the Cascadian Subduction Zone, so for me, whatever power this movie had actually did lie in posing the huge question: How would I personally face my certain death, given time to consider it? Not that there will be any warning for the magnitude 9 earthquake we’re sitting on top of, but I think about it.

Most of us like to believe we’d be brave and self-sacrificing in a dire situation–and that’s what action stories are for, in general. But most of us would like to imagine that when some inevitable doom is imminent, as it becomes in this film, we would face it with whatever we deem to be dignity–and that may be what these doomsday stories are for.

So while this movie was remarkably flawed, and deserving of its Metacritic score of 40, I did find some value, and some emotion, and quite a bit of catharsis in it by the end.

Valerie: Ah yes, this is exactly my point, Anne. The thing you reacted to was very personal; considering and facing your own death. Although I didn’t mention it above, this is exactly the issue that Robin Lerner (Vanessa Redgrave) is dealing with. Her scenes are some of the most poignant and her story one of the most relatable (betrayal and facing death with dignity).

I think if the film had followed fewer storylines then it would have had time to develop them in a more satisfying way. Any of the storylines had the potential for huge emotional impact. And of course, empathy isn’t about whether the audience has had exactly the same experience as the characters. It’s whether we can relate to the emotions of the characters. Is there a point of commonality, or humanity that we recognize?

I think Deep Impact was simply trying to do too much; it tried to cover too broad a canvas in too little time and as a result none of the individual stories were as rich as they could have been. Imagine if this same story had been told in long-form television series like Breaking Bad, or as a mini-series like Good Omens.

As novelists, there’s a huge lesson to be learned here. If we have a story of epic proportions, we’d be wise to either consider a series of novels, or find specific, relatable, human moments to build the story around.

Listener Question

To wind up the episode, we take questions from our listeners. This week’s question is from Kim, who dropped this on us and ran off on vacation, leaving us to answer it without her.

Kim wrote: As a Story Grid Editor, I can see the global movements for a client’s story and how the scenes fit into that story fairly easily, or at least get to the bottom of it all with using the triple threat of Story Grid tools, my client’s intention and reason for telling the story, and my own intuition. But when using Story Grid tools to analyze and revise my novel, I admittedly keep getting stuck.

Here’s my question: Since the spreadsheet tracks the turning point for each scene, it seems presumable that a story could technically have scenes that work, aka turn, but not necessarily be great scenes (with all five commandments) and not necessarily contribute to the story. If the 15 core scenes on the foolscap track with the global genre, how do we ensure that our other 45 scenes are really doing their job? Especially if we are writing a story that not a straight arch plot story? What I’m really asking is how can I look at my scenes to ensure that it a scene is a) is worth having in the novel and not a darling I should cut, and b) good enough / complete enough?

Leslie: Thanks, Kim. This is an excellent question. You can have scenes that work (ones that turn and are structured according to the Five Commandments) that don’t really work in the context of the story. But how can you tell? This is a big question, and the answer could fill multiple episodes of the podcast, but I’ll share an analogy that helps me when thinking about this problem.

I think of the scenes in a story as evidence in a criminal trial where the prosecution must prove certain objective facts, but can also prove other facts that support the required ones. For example, in a burglary case, the State must prove the defendant entered a building without permission with the intent to commit an offense (like theft or assault). If the State can’t prove those facts, as a matter of law, there can be no conviction. Think of those necessary facts as both the Obligatory Scenes and the 15 Key Scenes. If you don’t have them (and if they don’t turn on the global life value), you have a collection of scenes, but not a story that works.

The prosecution can admit evidence of other facts, for example a prior conviction for a substantially similar offense, motive, or actions after the offense that tend to support the defendant’s guilt. These specific facts are not required, but they are relevant to the question of guilt. You can think of these as the other forty-five scenes in your novel. You can determine relevance by how the story event in the scene affects the global life value.

The State is not permitted to introduce evidence that’s not relevant to the question of guilt. For example, evidence that the defendant regularly drives over the speed limit says something about their character, but is unlikely to be relevant in a trial for burglary. Showing that the defendant was obsessed with a certain author is relevant to their motive for breaking into an antique book store with the intent to steal a first edition by that author. A trial judge deciding whether to admit the evidence should ask if the fact supported tends to support or undermine the defendant’s guilt.

In the context of your story, again think about whether each scene moves the global life value related to the central conflict or moves the life value of a subplot that affects the global life value in some way. This is a less objective standard than you would use for the 15 Key Scenes, so it is squishier. When you make this assessment, you do so from your role as creator of the story, knowing how it all works out, not from the perspective of the reader who is missing key facts. But for every scene, ask yourself, what does this mean for the global story, and how can I make it mean more and have a greater impact?

Anne: I love this legal analogy! I love the idea that as the author of a story, I need to “make my case” systematically.

I’ll just add, in more purely Story Grid terms, that the 15 Core Scenes are inciting incident, turning point, crisis, climax, and resolution (times three, one set for each of the three acts) and what’s not in there are all the progressive complications. So my answer to Kim would be that many of the other 45 scenes have to complicate things–and complicate them progressively–between the inciting incident and the turning point of each act.

And as Shawn and I have been discovering in the Masterwork Experiment podcast, looking at Annie Proulx’s Brokeback Mountain, there is also room in a well-written story for scenes that are really more transitional or scene-setting, where we might say the “turn” is simply Point A to Point B, or Time X to Time Y.

If you have a question about any story principle, you can ask it on Twitter @storygridRT, or better still, click here and leave a voice message.

Join us next time as Valerie takes us on another psychological thrill ride with The Girl on the Train. Why not give it a look during the week, and follow along with us?

Your Roundtable Story Grid Editors are Jarie Bolander, Valerie Francis, Anne Hawley, Kim Kessler, and Leslie Watts.