This week, Jarie pitched Crazy Rich Asians as a great example of a Modern Love Story. The film was directed by Jon M. Chu from a screenplay by Peter Chiarelli and Adele Lim and based on the book Crazy Rich Asians by Kevin Kwan.

The Story

Global: Love > Courtship

Internal: Worldview > Maturation

Subplot: Society > Domestic

- Beginning Hook – When Rachel goes with her boyfriend Nick to Singapore to attend a wedding, she visits her friend’s house for dinner where she finds out that her boyfriend Nick is from a crazy rich family. Rachel must decide to be herself or tell lies. She chooses to tell the truth.

- Middle Build – When Rachel goes to the bachelorette party, she realizes that certain family members are against her. This is confirmed when they are making dumplings and Nick’s mom says she will never be good enough. She must decide to stand up or back down. She decides to stand up by going to the wedding.

- Ending Payoff – When Rachel is confronted with the news that she is illegitimate by Ah Ma and Eleanor, she breaks up with Nick and confronts Elenor over Mahjongg and says she does not want Nick to lose his mother again. Nick shows up on the plane to New York and proposes with Eleanor’s ring. Rachel says yes.

The Principle – Jarie – Modern Love Collides with Tradition

Love is universal yet cultures and traditions handle it differently. To some cultures, love is not as important as duty to one’s family. Still others feel that love grows over time and the young should rely on elders to make a match.

How authors deal with modern love colliding with tradition in different societies and cultures makes for great stories. We see some of that in Sense and Sensibility where status is much more important than loving someone for who there are.

A lot of love stories use this class-culture divide to interject some obstacles for lovers to overcome. Crazy Rich Asians is no exception.

Like Joy Luck Club before it, Crazy Rich Asians uses the backdrop of culture to add tension to the situations lovers find themselves in. Now, I know that Joy Luck Club is not a love story but the love stories within it do carry the moral weight of the culture they find themselves in — just like Sense and Sensibility does.

For Crazy Rich Asians, I’m going to go over some of the editor 6 core questions, like I did for Sense and Sensibility and put the rest in the notes. The particular ones I want to go over are obligatory scenes and conventions that showcase the collision between modern love and tradition/culture divide. The particular scenes I’m going to look at will be related to Harmers since there are a lot in this movie.

Before we do that, let me explain what I mean by modern love since clearly the time frames between Sense and Sensibility, Joy Luck Club and Crazy Rich Asians are vast yet each as a modern love battling tradition in them.

Modern love stories take on the taboos and social norms that align themselves again two people finding true love. Brokeback Mountain is a great example of a modern love story that battled the taboo of being gay and in love even though it was set in the 1960s.

These modern love stories push up against established norms to attempt to transcend the barriers that society or a culture puts on who can love whom. It’s the ultimate rebellion. Audiences love them because it’s the purest form of expression and gives the middle finger to the oppression that rigid, totalitarian hierarchies levy when our freedom to choose is suppressed.

Kim – Hear! Hear! I love the mix of the Love story with the Society rebellion. As we’ve seen with Brokeback Mountain, or even say Romeo and Juliet, love doesn’t always prevail against tyrants the way we hope it would, because tyrants have so much power over life and livelihood. But when the lovers do triumph against oppression, it’s hard to find a more fulfilling feeling.

Jarie – Indeed. It’s fulfilling on so many levels. There are several love stories in Crazy Rich Asians but I’m only going to focus on the main one between Rachel and Nick. Some of the other ones do come into play but only to showcase the peril if established norms are not met. I’ll also look at some of the Obligatory Scenes and Conventions of Rachel’s Worldview > Maturation since they are clearly laid out in this story.

#1 What is the Global Genre and the Value at Stake?

Global Genre: Love > Courtship

Global Value at Stake: Indifference to Commitment

Internal Genre: Rachel: Worldview > Maturation

Internal Value at Stake: Naiveté to Sophistication

#2 What are the Obligatory Scenes and Conventions of the Global Genre?

Obligatory Scenes:

- Lovers meet

- Happens off stage

- First Kiss or Intimate Connection

- Happens off stage and Sharing dessert in the bar

- Confession of love

- Nick tells Collin that he wants to marry Rachel and show him the ring.

- Rachel mouths I Love you to Nick at the wedding

- Nick proposes to Rachel along the water.

- Lovers break up

- Rachel runs away after Ah Ma and Eleanor reveal that her father is not dead and that she is an illegitimate child.

- Proof of love (Core Event)

- Nick proposes to Rachel and vows to leave it all behind.

- Rachel turns down Nick and tells his mother over Mahjong that she loves Nick so much that she does not want him to lose his mom again.

- Lovers reunite

- First attempt: Along the water where Nick proposes.

- On the plane where Nick proposes to Rachel with his mom’s ring.

Conventions:

- Triangle

- Amanda Cheng <-> Nick (ex-lovers)

- Helpers

- Colin and Araminta

- Oliver “Oli”

- Peik Lin

- Harmers

- Eleanor, Nick’s Mother

- Nick’s family and childhood friends.

- Gender Divide

- Traditional men/women roles in the Asian culture.

- External Need

- Being accepted for who you are and not what you have or where you came from.

- Opposing Forces

- Social status

- Nick being next in line to take over the family business.

- Secrets

- Nick keeps from Rachel that his mom is “okay”

- Nick keeps from his mom that he is dating Rachel

- Nick keeps from Rachel that he is from a rich family

- Nick was supposed to move home last year

- Rachel does not keep secrets from Nick

- Rituals

- Enjoying food together

- Moral Weight

- Lovers inherit the baggage of the families of their lovers as well.

#3 What is the Point of View/Narrative Device?

3rd Person Omnipresent + Free indirect style

#4 What are the Objects of Desire (Wants/Needs)?

Wants: To find a partner to share a life with

Needs: To be loved for who they are and not what they have or where they came from.

#5 What is the Controlling Idea/Theme?

Love triumphs when lovers remain true to themselves while also accepting where each of them came from and bring to the relationship.

#6 What is the Beginning Hook, Middle Build, Ending Payoff?

See Above

What I really like about Crazy Rich Asians is how they set up the conflicts to come by the montage of all the texting going on between Nick’s extended circle of friends, which starts in the bar at 0:06:28 with Radio1Asia sending out a picture of Rachel and Nick kissing. It ends with a bible reading where everyone’s cell phone starts dinging with the news. Modern meets traditional. In that scene, we are now introduced to the main antagonist to our protagonist Rachel — Nick’s mom Eleanor.

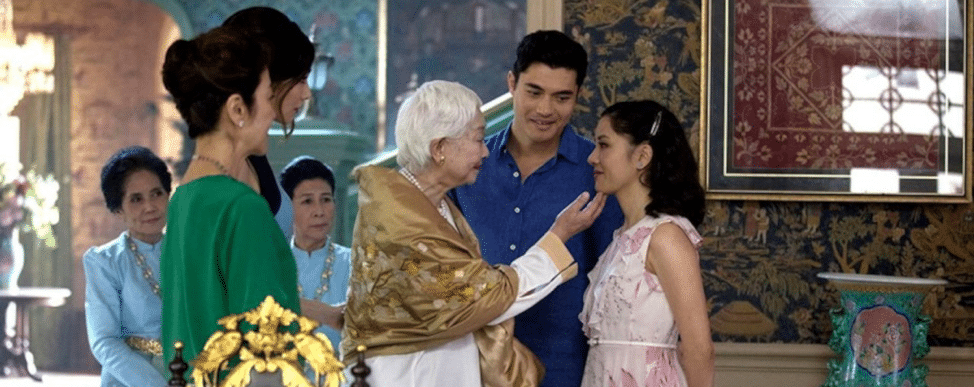

When they first meet, you can feel the tension and Eleanor sizing up Rachel. The questions Eleanor asks are all about pedigree since she wants only the best for her son. While the first meeting is cordial, you get the sense that Eleanor is holding back but this scene at 0:51:05 reveals what she is really thinking:

JACQUELIN: It’s so nice to having Nick back home. But he seems different.

ELEANOR: When children are away from home too long, they forget who they are.

Oh snap! If you didn’t figure out that Eleanor is not happy with Nick (and Rachel), then that line should have convinced you, at least a little.

There are even more hinderers that keep getting in the way. Like Nick’s ex-girlfriend Amanda, who in a split back and forth scene between Nick/Collin and Amanda/Rachel lays out what Rachel is up against right after Nick tells Collin he wants to marry Rachel. This whole sequence, which goes from 0:58:38 to 01:01:32, is when Rachel figures out that it’s going to be an uphill battle for her to be with Nick. It also happens to lead to the midpoint shift which harkens back to The Godfather by innovating on the Horse Head in the Bed Scene.

Collin’s advice on what it’s going to be like for Rachel if she marries Nick is the moral weight of the story, which is do you really want to subject your lover to the baggage of your family. It’s a great way to innovate the harmers conventions and to showcase the other subplot of this movie which is the Society > Domestic.

What puts the sting on it even more is that Amanda sends a text to the other girls on the island which reads — She’s on the move. Hook, Line, and SINK HER! This is the setup for what is to come.

Although the Fish in the Bed Scene is a shock to Rachel, it’s not the worst of the harmers. That honor goes to Nick’s mom, Eleanor, who over the family tradition of making dumplings, lays down her disapproval of Nick’s choice in Rachel. He harkens back to Rachel’s passion for teaching with this monologue that starts at 1:10:21 and ends at 1:10:39. The setup is that Rachel was admiring Elenaor’s engagement ring.

ELEANOR: It’s nice that you appreciate this house and us being her together wrapping dumplings. But all this doesn’t just happen. It’s because we know to put family first, instead of chasing one’s passion.

Speech in praise of the villain anyone. Ah but soon after, you get a hint as to why Eleanor is the way she is and that’s part of the Society > Domestic message that is hinted at throughout the whole movie. Then, just when you might feel some empathy for Eleanor, she says this to Rachel at 1:11:57 to 1:13:21.

ELEANOR: I’m glad I found you. I’m afraid that I have been unfair.

RACHEL: Oh, no, you know what? I’m sorry. I made an assumption. I didn’t mean to offend you.

ELEANOR: Not at all. You asked about my Ring. The truth is. Nick’s father had it made when he wanted to propose to me because Ah Ma would not give him the family ring. I wasn’t her first choice. Honestly, I wasn’t her second.

RACHEL: Gosh, I’m so sorry. I had no idea.

ELEANOR: I did not come from the right family, have the right connections. And Ah Ma thought I would not make an adequate wife for his son.

RACHEL: But she came around obviously.

ELEANOR: It took many years, and she had good reason to be concerned. Because I had no idea the work and the sacrifice it would take. There were many days where I wondered if I would ever measure up. But having been through it all, I know this much. You will never be enough. We should head back. I wouldn’t want Nick to worry.

Okay. That’s the real speech in praise of the villain and we now see why Eleanor is the way she is. In true Eleanor fashion, she raises the stakes by a power of 10 by hiring a private investigator to check into Rachel. She finds out that Rachel’s dad is not dead and that Rachel is illegitimate. That leads Rachel to flee and break up with Nick. Another power of 10.

What I do find interesting and a lesson for writers is how the setup that Rachel is a game theory expert reveals itself as useful in her quest to play the game that the matriarchy of the Young family is throwing at her. It’s a perfect example of her gift expressed but more importantly, it’s a great way for her to assert to all the harmers that she is willing to fight their petty, traditional ways so she can be with Nick. Or does she?

Rachel’s proof of love scene is pretty darn awesome in that she will give him up so that he won’t lose his mother again. Game, set, and match to Rachel. It’s an innovative way that her gift is expressed and the proof of love scene. Even better, they are playing Mahjong. It also puts Eleanor in her place and adds enough tension that we don’t know how it will end. That’s why it’s heartwarming when Nick proposes with his mother’s ring on the plan and Rachel accepts.

Leslie – Spotting the Global Genre Among Subplots

Writers often present a premise or scenario—a character in a setting with a problem—then ask, what genre is this? My answer is almost always, that depends, what do you want it to be? Another way to think about this is, what point do you want to make? What is the challenge or opportunity related to human needs you want to explore?

The same characters, setting, and situation could give rise to several different stories with different genres, depending on how it’s executed. Incidentally, this is part of the reason we sometimes disagree about the global genre of a story.

The characters face multiple levels and types of conflict, both external and internal, in almost any story that’s longer than the shortest of shorts. We choose one Global Genre, and this should be the main conflict, but as is the case in life, other things come up, usually when it’s least convenient.

A subordinate conflict might be the catalyst or the backdrop for the main conflict. A conflict in the external world should complicate the internal one and vice versa.

Again, we stress how important it is to pick a single Global Genre, what the story is really about, determining the life value the 15 key scenes turn on and the change described in the Controlling Idea/Theme. But if there’s not more going on than that, chances are the story won’t land and will be boring. This is particularly true in a love story where we need forces inside and outside the lovers to push them together while pulling them apart.

So let’s take the characters, setting, and circumstances of Crazy Rich Asians. It’s clearly a love story. Our primary protagonists are lovers, and the main question that pulls us through the story is whether the Rachel and Nick can and will commit to one another. The creators present a buffet of other romantic relationships—some of which are all business—as contrast or to express various opinions on the meaning of love and what makes it successful. (In this way it has the flavor of Love Actually, though the structure, tone, and point or message are quite different.) It’s all about love, but there are other subordinate conflicts that complicate and complement the central problem.

First, the lovers experience conflicts between what they want and need. They want to be together, but there are competing interests. Rachel has a passionate interest in economics (though it would have been nice to see more of this throughout). Nick is the heir to his family’s multinational business. Either of these conflicts could easily become a Worldview or Status story with the love story as the thing that makes them question their calling in life.

Of course, Worldview-Maturation is not a stretch because it’s often baked in to the Courtship Love Story. The lovers have to abandon one or more naive belief about themselves, others, or the world to be capable of authentic love. But we’ve also seen Worldview-Maturation stories with a love subplot. In About Time, Tim’s pursuit of love and connection serves as the backdrop to his Worldview shift. You could easily take the same circumstances and make it about love, but as written and executed it’s about time, how we see it, and how we spend it.

Status stories are about a character’s rise in social standing and what they’re willing to do or sacrifice to achieve it, but again, we can have love story subplots in global Status stories. For example, Rocky is a Status Sentimental story about Rocky’s attempt to rise within the boxing world. His relationship with Adrian complicates things for the better. If he sells out, he risks his relationship with Adrian.

How do you figure out which genre is global in a masterwork you want to study and possibly model? And more importantly, how do you decide which genre is global in your story? You have to figure out what the story is really about.

- What’s the life value at stake? Individual scenes within the story might turn on a wide range of life values (states or conditions), but what do the fifteen key scenes turn on? What is the most important change from the beginning to the end of the story? Is it about love, the way we see the world, power struggles?

- What basic human need is threatened by the force of antagonism? Is it love and belonging, is it about self-respect and self-esteem, or is it about self-actualization?

- What does the protagonist want, and what do they need? Do they want love and need to see things differently? Or do they want autonomy and freedom and need to adjust their definition of Success to make that possible?

- What’s the Controlling Idea/Theme? The Controlling Idea/Theme is a concise statement of the resulting life value and the cause of the change. This is the main message of the story, and you don’t always know it going in. But thinking about what it could be will help you decide what’s the main event and what’s part of the scenery.

When we do a Story Grid Diagnostic, we read and analyze the manuscript first to get an objective view of what’s actually on the page. Then we have a conversation about the writer’s intent. The goal is to help the writer close the gap between what they’ve written and the vision they have for the story. So we don’t say this is what you’ve written and you’re stuck with that. We ask, what can you add and subtract from the global story to fulfill the reader expectations of the genre you intend? The main takeaway here is that you get to choose, and you should.

Anne – What’s the middle build made of? Looking at the scene types abstractly.

In Crazy Rich Asians we have our 15 Core Scenes, more or less, as Jarie has pointed out. But what interests me is the containers the writers decided to put those scenes in.

They decided to put most of them into parties. The middle build begins with a formal party, goes on to an intercutting of two wild parties happening simultaneously, and ends as the big wedding and reception get underway.

What purpose do party and ballroom scenes scenes serve in a story? In almost every case, their main function is to show class and culture differences; to get a wide variety of people together in socially demanding circumstances and let them duke it out over who dresses better, who can dance, who’s a wallflower, who’s the belle of the ball, and so on.

These scenes also show off wealth, because that’s what big parties, dances, and evening affairs are all about in real life. Even a party in a rustic or low-wealth setting will have people in their most attractive clothes, serving their best food, and probably behaving differently than they do at home, thereby revealing their roots, their conflicts, and their desires.

Since Crazy Rich Asians is almost entirely about how class, culture and wealth differences stand in the way of two lovers committing, the choice to set the whole middle build in a series of extravagant parties was pretty sound.

The Big Evening Party

The middle build opens with Rachel and her Herald sidekick Paik-Lin arriving at the splendid manor house belonging to her boyfriend’s aristocratic family, and it could just as easily be Elizabeth Bennet, 200 years earlier and 7000 miles away, beholding Pemberley for the first time. Does that make it a cliché? I don’t think so, and if it is, this one is made fresh by a setting which, for a Hollywood movie, is new and interesting to much of the audience.

Within the big evening party sequence there are four separate beats where Rachel commits increasingly severe social faux-pas: she makes a table-manners mistake (drinking from a finger bowl); she acts overly American in an non-American environment (hugging Nick’s mother); she mistakes a servant for a family member (speaking to the old nanny as the honored grandmother); and she spills something on the leading man’s expensive suit (red wine, white suit). Each instance proves to her and to us that she’s not as sophisticated as she thought.

The formal evening party contains a number of two-person conversations in which a truth comes out. What could be the difference between those and most of the two person conversations in a room that were so repetitive last week in The Girl on the Train?

The difference is the party itself. How long can they talk before they have to get back to the party? How long before someone interrupts? These are subtle ticking-clock elements. Does noise cause miscommunication? Are they being overheard? It’s a small but important difference in scene type because it adds suspense. We see and hear other characters, too, making it more dynamic and engaging.

The wild daytime parties

Now we come to the bachelor and bachelorette parties, which happen simultaneously and are intercut. They contain the same large-crowd gatherings, the same two-person breakout scenes, and the same display of ostentatious wealth as in the evening party sequence.

The big difference–and this is a useful tip–is that these parties are happening in broad daylight, in the absence of elders, without any constraints on the young party goers’ actions. They are rich, they are young, and they are free, and this comparative freedom means that harsher and larger truths come out in less refined ways, increasing the Rachel’s discomfort and her doubts about her relationship.

Now, one way to innovate in your story is to use a scene type associated with a different genre than the one you’re writing in. But don’t fail the way they did in this story. Some of the young women leave a large dead fish on the protagonist’s bed at the bachelorette party, with a warning message “written in big fat serial-killer letters.” This act of gross violence didn’t work as comedy and fell strangely flat in a love story. Yet I did recognize it as a scene type I’ve seen in a number of thriller, crime and horror stories–where it should probably remain.

Note: while the obvious corollary is the horse-head scene in The Godfather, there are many other instances of some bloody human or animal body or body part being delivered as a shocking warning–the severed finger of a hostage, the severed head in Se7en, the boiled rabbit in Fatal Attraction. None of those are love stories. The scene type does not transfer well!

That’s just a flyover of two of the major party sequences of the middle build.

Complete beat breakdown of the middle build

- First glimpse of magnificent estate is just like Lizzie seeing Pemberley for the first time.

- Handsome man in evening wear makes a grand appearance–with enough lead time for the quirky sidekick and Herald character to comment on him so we, the audience, fully understand his place in the scheme of things.

- Large party scene with tons of beats. The party takes a full 15 minutes of screen time

- Band with singer–live entertainment, sets mood, continues to reveal class, culture and mood

- Montage of richly-dressed guests contrasted with quirky sidekick’s lower-class behavior and freedom

- The social faux pas, number 1 (drinking the finger bowl)

- Cultural food-preparation beat establishes lavishness, cultural milieu, sense of celebration

- Meeting the Mother, another social faux pas (the inappropriate hug) establishing further cultural differences, mother not impressed. Here is the major hurdle to the love story.

- Heroine reveals her life story in a few lines of dialogue, then “she hates me.”

- Meeting more of the family–gracious ones, rude ones–a display of the “types” used to deliver some exposition

- Rescue from importunate rude family member

- More hostile family members (a weird series of two-shots similar to a job interview scene, except multiple “bosses” and only one “applicant”)

- Big faux pas number three: mistaking the old nanny for the grandmother.

- A wife discovers her husband’s infidelity by reading a message not meant for her

- Major faux pas number four: spilling red wine on a guy in a white suit, to get rid of him so we can hear from a new secondary character, the fabulous gay family member who will become an ally in the war between the ins and the outs.

- Two person confrontation in a room, mother and son variant, with a love-story staple, the reveal of bare-chested male pulchritude, in which more exposition is delivered more or less naturally in dialogue

- Three-person walk-and-talk through the large party scene, as people stare at the protagonist, who is out of place.

- A grand royal entrance and the protagonist introduced to the queen who has all the family power.

- Two-person conversation in the midst of the crowd, agreeing.

- A contrasting large party scene, daytime, casual, loud, all young people, showing the other, younger side of the lifestyle. One character delivers on-the-nose references to Cinderella–this will happen again. THIS WHOLE SECOND PARTY SEQUENCE takes up 12 minutes of screen time and brings us to the midpoint shift

- An insult to the lady gets a chivalrous reaction from the gentleman. No fight, though. Friend calms him down.

- Women’s party, equally ostentatious, crowd scene of wild shopping, screaming, lifestyles revealed in montage

- Two-person conversation in the midst of the crowd, seemingly friendly

- Two person conversation, more or less on a beach, in which a truth comes out: one man reveals to the other that he plans to propose to the protagonist. Includes trope of getting the ring box out of a pocket.

- Two person conversation, massage table variant, in which some truths come out, masquerading as friendly talk. (Nudity on massage table creates similar constraints to Conversation In A Car: it’s not that easy to get away from the unwanted conversation.) These two conversations cut back and forth on the same subject, revealing two sides of a story, one to the protagonist and the other to the audience, building up the obstacles to love and tearing down the naivete of the protagonist.

- TOTALLY OUT OF PLACE SCENE with bloody message scrawled on windows, like something from a thriller. Really weird.

- Two person conversation on a beach, friendly, but truth comes out.

- Lovers reunite (in a sense, the two pre-wedding parties separated them), in a two-person confrontation between main protagonists–in a room (hotel lobby–serves as a transition, showing characters back at their hotel, but a bit distancing, since they’re not in hotel room, but a public space). Truths come out, they make up.

- Festive family food preparation scene. Dumplings. Generally a celebratory scene type, similar to large family dinner. Laughter, family stories. This reduces to…

- Two-person confrontation (dinner table variant as others look on in varying degrees of discomfort)–between Rachel and Eleanor.

- The second “arrival of the queen,” (Ah-Ma, Grandmother) reinforcing the previous encounter between queen and protagonist

- Two person confrontation, staircase variant: more truth comes about. This is where the idea of sacrifice comes in strongly. Staircase is not incidental, it’s highly symbolic as Eleanor literally backs Rachel down the stairs, putting her into her place.

- Conversation in a car, two people (main protagonists). More truth comes out. Why? Shows movement, freedom in this case (the car is a getaway).

- Two person conversation, outdoor cafe variant, protagonist and sidekick, Truth comes out, Herald-fashion.

- Dresses the Part Montage! complete with Gay Best Friend cliché

- Caught shining. Showing up in the chosen gown. Includes trope of walking through the gauntlet of journalists with cameras and microphones.

- Two person conversation in a car, in which truth comes out (marital infidelity), complete with having to stop the car so one person can escape

- The third big party set-piece in this movie begins with the wedding itself.

- Three person conversation in the church, exposition as gossip, the wicked stepsisters or three fates, or similar, trying to maintain power

- Completely out of the blue two-person conversation with a character who appears only in this scene and no other: a payoff that had zero setup. The place to have set it up would have been in the opening scene in Rachel’s lecture on poker and economic theory.

- Wedding scene. Absolutely bog-standard, in which the two not-yet-engaged lovers make heart-eyes at each other, inspired by the beauty of their friends’ wedding.

- Four-person confrontation at a big party, when in the All Is Lost Moment, an unknown truth is dropped on the protagonist and she admits defeat.

Three non-party scenes worth examining

Now I’d like to touch on three scenes outside the party sequences that I thought were well done.

The first is a food preparation scene. Rachel and her boyfriend join his family around the big dinner table where they all participate in making dumplings. Food scenes are an excellent way to bring a particular culture or tradition to life, and to represent tradition itself.

You introduce food so you can have different characters reacting differently to unfamiliar tastes and foodways. You put them around a table to show up differences in table manners, which emphasizes different backgrounds. The family around a table, especially with an outsider present, is a natural place to tell family stories and reveal prejudices, and that’s what happens in the dumpling-making scene.

The second scene type I particularly liked was a conversation in a car. An interesting variant in this film is that the car is chauffeur-driven. When Astrid raises the privacy barrier before confronting her husband with the truth, we know some unpleasant secret is coming. Suspense! Conversation in a car is very different from conversation in a room, because the moving car is hard to escape, so at least one person in the scene is like a prisoner, with little choice but to hear what the other has to say. So the other useful variant in this scene is when the limousine screeches to a sudden halt, and the husband leaps out, slamming the door.

The third scene type that I particularly enjoyed was friends having coffee. Protagonist Rachel meets up with sidekick Paik-Lin at an outdoor cafe. Because there’s no conflict between them, this conversation serves as comic relief and an opportunity for the sidekick to become the mentor and give the protagonist just the nudge she needs to face her next ordeal.

Though friends having coffee is an extremely common scene type, this one is freshened by its unfamiliar backdrop–not only Singapore, but a poorer part of the city than we’ve seen so far. The “local color” gives this otherwise common scene type some verve.

Takeaways for writers

As you read or watch a story, let yourself be aware of having encountered similar scenes elsewhere. Notice when a scene in a book or movie leaps out at you as something you think you’ve never seen before–as I’d never seen how Singapore’s ultra-wealthy throw parties in Crazy Rich Asians. Then ask yourself, “are there recognizable elements here?”

Start to build a grab bag of scene types or beat types that you can reach into when you’re stuck in your writing. Experiment with them. Maybe structuring a whole middle build around four enormous parties makes no sense for your story, but could some form of party or gathering serve? Maybe there is no coffee in your story world, but is there some equivalent to a coffeehouse? Some neutral place where two people can meet and develop their friendship?

Of the wide-but-not-infinite array of ways characters might interact, and the wide-but-not-infinite choice of settings in which they can do so, which one does your story need?

Not a meal scene because it’s dinnertime, but because you need to embarrass or shun a character, or lull them into a false sense of happiness which you’re going to take away.

Not a ballroom scene just to describe fabulous gowns or chamber music, but because your character needs to be squeezed on all sides by social rules and be judged for her appearance.

Not a conversation in a car because you need to get characters from one place to another, but because you need them to have a difficult talk that at least one of them doesn’t want to have, and can’t escape.

There’s so much more to work on in this realm of stories. For now, though, Crazy Rich Asians, while not a masterpiece of story structure, does make good use of variety in scene types to keep the middle build moving along at a decent clip.

Kim – Stories that don’t (completely) work

As much as I love a story that pushes against an oppressive society, I have to admit when I first saw this story months back, on an airplane flying home from the Story Grid even in Nashville I think, I came away with a mediocre experience. There were moments I enjoyed but I didn’t achieve that satisfying hook, build, payoff experience I crave and only a great story can provide. Which made me sad because I always want to love every story I take in, and I was really excited about the representation of an Asian majority cast. I’m still excited about that.

Since I’m studying stories that don’t work this season, and this love story didn’t work that well for me I wanted to get to the bottom of why that is, and make some editorial recommendations for revisions. But I had a hard time nailing down what exactly those things were.

Anne and I were talking offline about finding stories that don’t work to study and she pointed out a simple but profound truth: “That’s the trick with stories that don’t work. Either it’s SUPER obvious, or else you have to go digging for tiny things.”

Digging up small things

Crazy Rich Asians seems like the latter. So while this is not an exhaustive list, here are some of the smaller things I was able to dig up for myself:

- Undeveloped Status Quo – we don’t get much time at all with Rachel and Nick before they leave for the wedding. We don’t get to see them in their homes or their regular life enough to understand why Rachel says, “We’re not first class people, we’re economy people.” The fact that Nick has kept his family’s wealth a secret would be better served if we could be “shown” the difference between how the live in NY.

- Editorial recommendation: add a scene or even a transition where we get to see their home. Also are they living together? And what does Nick actually do in NY? Does he have a job? Establish more details that support Rachel’s naive worldview at the outset.

- No “lovers meet” scene – not only is not on screen, in linear time or a flashback, we don’t even get to hear the story! No one even asks them about it! We get a strange unconnected prologue but no lovers meet? Boo!

- Editorial recommendation: the reader is wondering so at least let it be a cute story that the couple gets to tell, possibly in front of some harmers. In the case of Nick and Rachel, I’d recommend putting it during the Dumpling scene so the whole family is there to hear about it. It doesn’t have to long, just something to address the gaping hole in the reader’s mind.

- Progressive Complications / Rivals – Amanda is a small time rival that really only comes in at the midpoint. I like the fact that she is a shapeshifter and lures Rachel into a false sense of security. I naively believed she was going to be a cool friend and Rachel when I first saw the film. But for me, the shapeshift came too quickly and then what had been a tool (albeit a false one) quickly shifted to an obstacle and then became irrelevant.

- Editorial recommendation: establish Amanda earlier and/or draw her out longer, save her shapeshifter moment for a better payoff. Make her a more credible threat, not just a poke to Rachel’s self-esteem.

- No rival for Nick? There are a few mild mentions of how much Rachel loves her job, but there’s really no stakes in it. It doesn’t feel like a credible rival. And if this is supposed to be one of their major barriers, it could use some beefing up.

- Editorial recommendation: add some additional Performance-business subplot for Rachel, or at least demonstrate a bit more of her job and why she loves it. How is it making a difference? Basically get more specific. When she talks about her job have her speak more passionately, sharing specifics that may not make sense to the listeners but that she is excited about. Something that makes us feel like she couldn’t just move to Singapore yo be with Nick. She needs to be in NYU …

Overall structure and balance

These are the things that stood out that I was actually able to put a name to. There are other things about this story that are hard to pinpoint. When talking offline we mentioned some things like balance. Unlike Pride & Prejudice where the main love story is supported by love subplots that connect and drive the plot, or Love Actually where the mini plot of love stories each have their own narrative drive through the hook, build, payoff, in Crazy Rich Asians the main love storyline feels eclipsed by subgenres and subplots. It feels like structure of the story isn’t quite arch plot and not quite miniplot, it’s some unclear haze in between. My editorial recommendation aligns with what Leslie said earlier about knowing your global genre: get really clear about what you want the audience to experience and which story or stories best serve that goal and which structure (in this case arch plot or mini plot) carries the reader through that experience.

As I mentioned, when I first watched this film, my expectations were high for this to be a fresh and satisfying love story. But it wasn’t. When I watched the film this week, my expectations were better aligned and I found I enjoyed it much more. The power of the state of mind of the audience, whether reader or viewer, is always in play but it is something outside the author’s control, at least at the start. That’s what solid structure is for–to hijack the audience experience and guide them through the sequence of life value moments that create an arc of meaning. All your macro genre choices (from five leaf clover) and micro choices should serve this end.

In any story of any genre, getting specific is essential. This is the only way that the Life Values can be truly communicated to and experienced by the audience. For Worldview-Revelation this means we must define the factual information the protagonist is ignorant of.

Without this cohesion, we get at best an okay story. And telling stories is too important to settle for just okay.

Listener Question

To wind up the episode, we take questions from our listeners. This week we’re answering two related questions about genre that came from listeners on Twitter.

Jay Goranca asked, “Hi Story Grid. I’m a new fan. I’m writing my first two novels now. One is an action-adventure-horror and the other is a superhero story. Are these good genres for an aspiring Commercial writer?”

And Lesley asked, “Under the Story Grid schema my novel would be a Worldview narrative, with a Love story sub genre, but I’m not sure how UK publishers and editors view this. How should I refer to my genre I prepare to pitch to agents?”

Anne: Thanks, Jay and Lesley, for these questions. They represent a type of question that comes our way a lot, and we simply aren’t able to answer them in the way the questioner usually hopes. The only way to judge whether a particular type of story is good for an aspiring commercial writer, or to appeal to agents and publishers in a particular market, is to read and study.

What kinds of stories are at the top of the bestseller lists? You have to read some of them to discover how to categorize them in Story Grid terms. As we’ve talked about many times on the show, the Story Grid genre definitions are NOT marketing categories. They are structures for the writer, designed to help you build a story that meets the expectations of its target audience. The words you use to market your finished story to agents or publishers are going to be different. What we would call a Worldview Maturation story, agents and publishers might be calling “coming of age” this year, and something else next year.

If you’re going to pitch to agents or publishers, you need to know their terms. Does “action-adventure-horror” figure in the descriptions of what agents are looking for? Or are you really writing a thriller? Loading on extra terms, like Action-Adventure-Horror, just muddies the water, trying to be more things to more people than one story can be. Who or what is your villain? The answer is going to determine whether your story is more horror, or more action.

Let’s suppose that you figure out that you’re writing a thriller, or writing a worldview maturation story with a strong love secondary plot. Let’s suppose, further, that you’ve edited your story to the point where you’re confident that it works according solid story principles, with its 15 core scenes all turning on the same global values, and all the obligatory scenes and conventions for your genre in place.

NOW you need to hunt for recent titles that might be in the same genre, and look at how they’re presented. Go to the bookstore, if you’re lucky enough to still have one in your town, and read back-cover blurbs. Use Amazon or other online sources. You have to be able to talk about your book and pitch it in writing, using terms that the publishing world of today uses for similar books. It’s not always obvious. What seems crucial to you as the author might well be left out of your elevator pitch, and you might end up emphasizing things about your story that weren’t consciously in your mind when you first wrote it.

Read one-and two-star reviews of books that might be like yours, to understand cases where the story as pitched did not meet reader expectations. You’ll see cautionary tales everywhere about the dangers of pitching a book as a more popular story type than it really is. Read short descriptions of big bestsellers and learn to spot key words that communicate TO YOU what kind of story you’re looking at. Ask beta readers to tell YOU what kind of story they think they’re reading.

I wish there were a magic answer, but the answer is reading, research, grinding. This is work. It’s hard. You have to do it.

If you have a question about any story principle, you can ask it on Twitter @storygridRT, or better still, click here and leave a voice message.

Join us next time as Kim continues her study into stories that don’t work. We’ll take a look at the film Passengers and discuss what went wrong and how to fix it. Why not give it a look during the week, and follow along with us?

Your Roundtable Story Grid Editors are Jarie Bolander, Valerie Francis, Anne Hawley, Kim Kessler, and Leslie Watts.