It’s bucket-o-blood time as the Roundtable team tackles the Horror genre with Kimberly Peirce’s 2013 remake of the Stephen King classic Carrie, with Screenplay by Lawrence D. Cohen and Roberto Aguirre-Sacasa.

Click here to download our Foolscap Global Story Grid.

The Story

Here’s a synopsis adapted from Wikipedia.

In the opening scene Margaret White gives birth to Carrie and, believing the baby is a punishment from God attempts to kill her. But she can’t go through with it. The story picks up years later when Carrie is nearing her high school graduation.

While showering after gym class at school, Carrie (a shy, awkward girl) experiences her first menstrual period, and naively thinks she is bleeding to death. The other girls ridicule her, and one girl (Chris) records the event on her smartphone and uploads it to YouTube. Their gym teacher Miss Desjardin comforts Carrie and sends her home with Margaret, who believes menstruation is a sin. Margaret demands that Carrie abstain from showering with the others. When Carrie refuses, Margaret hits her with a Bible and locks her in her “prayer closet.” As Carrie screams to be let out, a crack appears on the door, and the crucifix in the closet begins to bleed.

Miss Desjardin informs the girls who teased Carrie that they will endure boot camp-style detention for their behavior. Chris refuses and is suspended from school and banned from the prom.

Carrie then learns that she has telekinesis and spends her time researching and perfecting her skill. Meanwhile, Sue (one of the girls who ridiculed her in the gym shower) regrets what she’s done and wants to make amends. She asks her boyfriend Tommy to take Carrie to the prom. Carrie accepts the invitation but when Margaret forbids it Carrie’s telekinetic powers are revealed. Rather than being amazed, Margaret believes it’s proof that Carrie has been corrupted by sin.

Hell-bent on revenge Chris and her boyfriend (Billy) come up with a plan to humiliate Carrie even further. In one of the most iconic moments of the story, Tommy and Carrie are crowned King and Queen of the prom at which point a bucket of pig blog is dumped over Carrie’s head. The video of the shower scene is played on giant screens and the graduating class laughs. The empty bucket falls on Tommy’s head and kills him.

Enraged, Carrie fights back using her telekinetic powers. She kills nearly all of the graduating class and staff, and burns down the school. Carrie escapes the fire and goes after Chris and Billy who are driving away. Still using her powers, Carrie flips the car into a gas station, setting it on fire, and killing them.

Carrie then goes home, seeking comfort from her mother, but is instead attacked by her. This is, without a doubt, the scariest scene in the film and Julianne Moore, who plays Margaret, is terrifyingly brilliant. Carrie kills her mother in self-defence and her grief causes their house to cave in. When Sue arrives, Carrie senses that she’s pregnant and throws her clear of the collapsing house to safety. Carrie stays with her mother’s body and dies in the house.

In the final scene Sue visits Carrie’s vandalized grave and places a single white rose by the headstone. As she leaves, the gravestone begins to break and Carrie’s angry scream is heard.

The Editor’s Six Core Questions

Read about the Editor’s Six Core Questions here.

1. What’s the Global Genre? Horror

Valerie

Global genre, Horror > Ambiguous: There are three different kinds of horror stories; uncanny (the force of evil is explainable, for example Frankenstein), supernatural (the force of evil is from the spirit world, for example Dracula) and ambiguous (the force of evil is not revealed). In Carrie, the reader is kept in the dark about the source of evil, and the sanity of the protagonist/victim comes into doubt. Robert McKee refers to this subgenre as the super-uncanny. (See Story, page 80).

We know that Carrie has the power of telekinesis, but this isn’t a source of evil, it’s a special power. Although she can be described as monstrous in her desire to destroy those who have hurt her, she is not a monster. She’s a bullied teen. It’s unclear, while she’s exacting her revenge, whether she is sane or temporarily insane.

Carrie is a prime example of an ambiguous horror story. The source of true horror (the monster, source of evil) is very hard to pin down. Is it Carrie’s mother, Margaret? This is one terrifying character, and Julianne Moore’s portrayal is fantastic. Margaret abuses her child, attempted to murder her as an infant and does stab her in the end. But what is it that causes this horror? Is Margaret mentally unstable? Is she herself possessed by the devil (although she accuses Carrie of being so)? Is religious fanaticism the only factor affecting her?

Is bullying the source of horror (or cyberbullying as in this version of the story)? Chris is indeed a force of antagonism, but she’s not a particularly powerful villain. She cowers quickly under her father’s demand to turn over her phone, and her peers reject her call for allegiance during the suicide-run scene.

Is Carrie’s isolation the source of horror (which began with the way Margaret has raised her, and has been reinforced through the other students treatment of her)? This is what causes Carrie to eventually lash out against the students, staff and her mother. Throughout her entire life she has been treated terribly, not because she had done something wrong, but because she is different. And society perceives this difference as a threat. Margaret sees Carrie as a punishment to her.

Morality > Punitive: Horror stories don’t require an internal genre. However, there’s an argument to be made for a slight one in this version of the film. In fact, it’s more of a nod toward an internal genre rather than a fully realized character arc. Carrie starts the story as a shy, troubled teen who is essentially a good person. She doesn’t seek revenge on Chris or the other girls for teasing her or posting the video. It isn’t until the blood is dumped on her at the prom that she finally snaps and lashes out, killing the majority of her classmates and destroying the school. For that, she is punished first by her mother and then by society. Her mother tries to kill her for going to the prom (literally stabbing her in the back) and society desecrates her grave.

It’s important to remember that Carrie’s goodness isn’t completely destroyed. When she realizes that Sue is pregnant, she saves her for the sake of the innocent child.

Carrie is often considered to be a worldview > maturation plot, but I don’t see it (at least in this film version). Yes, she matures physically when she gets her period, and is at first naive as to what’s happening to her body. But this is a very small part of the story. It’s used as the inciting incident, but is then done. Carrie is never naive about the way her classmates view her or her mother. Nor does she demonstrate naivete masked as sophistication. She wants to belong, and hopes to belong, but isn’t naive about her chances of being part of that culture. Even when Tommy asks her to prom she refuses at first. In her desperation to believe that someone might be kind to her, she eventually accepts. During that 15 minute prom scene, she begins to hope that maybe life is turning around for her. However, once the pig blood is dumped, her hope is dashed forever. Carrie’s view of the world at the outset of the film proves true. She doesn’t belong and is not accepted by her peers.

Additional Comments

Kim: This is not a typical Horror story. The external genres feels like a solid mashup of Horror-Ambiguous and Society-Domestic. For internal I’d argue for Status-Pathetic: a weak protagonist tries to rise and fails. I agree that she doesn’t really seem to mature, but she’s not sophisticated enough for it to be Punitive (which requires a character with sophistication and strong will from the outset). It’s not that she goes from good to bad and is punished, it’s that under those circumstances, her mind/will are too weak to do anything but what she did. Also, she does not have a strong mentor, which is a convention of Status-Pathetic and Status-Tragic—the mentor is absent or weak/weaker than the protagonists. In this case Carrie’s mother has weaker in mind/will than she is. For more information on Internal Genres, check out Leslie and my Fundamental Fridays post, Internal Genres Part 1: A Case Study in Nuance.

Leslie: Some of the genre confusion we’ve noticed arises in stories that seem to be a combination of some external genre with elements of Society. I suspect this may come from the fact that, in the US, Canada, Western Europe and similarly situated countries, the cultures have moved beyond pure Survival and Safety needs, and most people are free to form a romantic commitment with another person.

This doesn’t mean that there aren’t life and death struggles (in the US, we produce more calories than we need to feed the entire population, yet people go hungry, and many people are homeless despite the means to provide shelter for everyone). It also doesn’t mean that no one in this country faces safety and security issues (for example, kids have lockdown drills in public schools). Cultural hurdles still exist to forming committed romantic relationships.

What this means for the writer is that telling a relevant story in 2018 and beyond for the US and similar markets should at least consider how power struggles at different levels of society (family, work, government, etc.) impact the events of the story (this isn’t necessarily about politics, though that might come into it). But also we need to choose a single global genre and skillfully integrate subplots.

How do we do that? Find a masterwork in your genre that does this well. My hunch is that Kimberly Peirce was trying to accomplish something more than the final project suggests, but that different people/entities had different goals for the story. The point is that the reader or audience member won’t necessarily know why a story isn’t working for them. So we must do everything we can to tell a story that works while innovating our delivery on audience expectations.

Update: Since we recorded this episode, I’ve come to understand that the Society element we notice in a lot of stories is coming through what author Kim Hudson calls the Virgin’s Promise, which is an archetypal journey similar to the Hero’s Journey.

Click here to learn more about the External Content Genres.

Click here to learn more about the Internal Content Genres.

2. What are the Conventions and Obligatory Scenes?

Click here to learn more about Conventions and Obligatory Scenes.

Conventions for a Horror Story

Anne

The monster can’t be reasoned with. Possessed by a spirit of evil, it is here to devour and annihilate – The mother is so locked up in her own trauma and religion that she’s incapable of rational action. Thet religion represents the spirit of evil that consumes her. But maybe the monster here is really high school and bullying, embodied by Chris, who is unreasoning. If the monster is merely Carrie’s inherited psychic power–somehow her “heritage”–then we see that it does have more destructive control over Carrie than Carrie has over it till the climax.

Conventional settings within a fantastical world – What’s supposed to be a typical American high school is Carrie’s fantastical world–it’s her outer space, where no one can hear her scream.

Labyrinth-like, claustrophobic setting – The house where Carrie and Margaret live is dark and creepy and filmed in a close, suffocating way. Carrie’s internal landscape is extremely claustrophobic and everything in the way she moves through the world says that she’s locked inside her body.

Perpetual discomfort for characters and audience – Carrie’s tight, frightened walks of shame in the high school halls are juxtaposed with scenes of her increasingly liberated powers, which we know are deadly. Carrie’s mom is pure discomfort from beginning to end–creepy for us, creepy for Carrie, and a burden to herself, constantly trying for self-control.

Monster’s power is masked and progressively revealed – IF THE MONSTER IS CARRIE’S POWERS: Could newborn Carrie have already stopped her mother’s sewing scissors with her mind? We see her powers increase step by step from flickering electric lights to where finally she’s setting the school on fire, stopping speeding cars and bringing a house down on her own head.

IF THE MONSTER IS HIGH SCHOOL BULLYING EMBODIED BY CHRIS: She lashes herself into greater and greater fury and revenge for no really apparent reason, going from kind of a whiner to the perpetrator of a really nasty assault. As one reviewer mentioned, Chris as depicted here seems to be little more than a sociopath.

IF THE MONSTER IS MARGARET/RELIGIOUS FANATICISM: Her power wanes rather than grows throughout the story as Carrie becomes self-aware.

Monster remains off-stage for as long as possible – This convention applies if the “monster” is something like religious belief, which we get only glimpses of until the ending payoff when Margaret acts as the preacher to Carrie’s “congregation” and stabs her as part of some ritual. If the monster is Margaret herself, we see her clearly throughout the movie. I don’t feel that this convention is clearly met.

Use of technology. Victims experience horrific attacks at a remove via screens, radio, or other devices – Carrie’s enemies take videos of their attack on her, but we see the attack itself and don’t see the videos till the end. If the monster is defined as bullying, we see it directly and frequently. I don’t feel that the movie really meets this convention.

Additional Comment

Valerie: I agree that the monster remaining offstage is a convention the film doesn’t meet! This feeds into my discussion of narrative device. It takes away from the suspense of the story. As to the film’s not meeting the technology convention, I’m wondering if this is because the filmmakers all had a different view of what genre they were working in. I know we’re analyzing this version of the story, but I wish I knew the novel better.

Obligatory Scenes for the Action Genre

Kim

An Inciting Attack by a Monster: Carrie gets her period (“coming of age”) as well as endures the cruel torment of her classmates. Either or both seem to be the trigger for Carrie’s gift and the first flicker of lights, shortly followed by breaking the water cooler in the principal’s office.

A single, non-heroic protagonist is thrown out of stasis and forced to pursue a conscious object of desire: saving their own life. Carrie is thrown out of stasis when she gets her period and thinks she is dying.

Speech in Praise of the Monster: Carrie praises herself to her mother when she reveals her gift and tells her that she’s not evil, other people have it, it’s genetic, skips a generation, grandma had it. Carrie wants to be normal like the other kids at school so saying that her gift is normal is the highest praise she can give (and the opposite of what her mother is saying: evil, from the devil, witch).

The Victim at the Mercy of the Monster: After the pig blood and Tommy’s death, the entire school is at the mercy of Carrie.

A false ending: Carrie returns home from Prom seeking comfort from her mother, only to be attacked and stabbed. Carrie kills her mother and collapses the house on top of them both.

Protagonist becomes the final victim after a series of kill-off scenes of minor characters: Carrie is the final victim when she collapses the house on herself.

3. What is the Point of View? What is the Narrative Device?

Valerie

POV: Omniscient: We see the story from multiple points of view (Margaret, Carrie, Sue, Chris), which leads into narrative device.

Narrative Device: Suspense and Dramatic Irony

There are three ways to drive a narrative; dramatic irony, mystery and suspense. Dramatic Irony is when the viewer/reader knows more than the character. Mystery is when the character knows more than the viewer/reader. Suspense is when the viewer/reader and the character have the same amount of information.

Horror stories require suspense. When the reader is in step with the protagonist, he’ll be on the edge of his seat wondering what will happen next. Mystery can work under certain circumstances, but dramatic irony is the doom of horror stories. When the reader knows more than the protagonist, he loses interest very quickly.

Carrie doesn’t use a lot of suspense to create narrative drive, but when it does, the effect is chilling. Perhaps the best example is near the end of the film when Carrie returns home after the prom seeking comfort from her mother. Like Carrie, we know that Margaret has escaped the closet. We also know that her mood swings dramatically, so she can be either abusive to her daughter or nurturing. So, when Margaret hugs Carrie we think she will finally give her daughter the love and understanding she needs. It’s shocking then, when Margaret whips out the knife and stabs Carrie in the back. This is the beginning of an intense fight scene in which both mother and daughter are ultimately killed.

Narrative drive in Carrie is primarily achieved through dramatic irony and unfortunately, this makes for a less satisfying horror film. For example, even for viewers who are not familiar with the story, it’s not difficult to figure out that Carrie is on her period. Carrie thinks she’s bleeding to death, but we never fear for her life. In fact, to a modern audience, this scene plays as unbelievable. We also know that Chris has uploaded the video to YouTube, and is planning to dump the pig blood over Carrie’s head at the prom. While the pig blood example does create a sense of anticipation, it also takes the wind out of story for a while. The viewer is way ahead of Carrie at this point in the story and is forced to sit through another 15 minutes before the event actually happens. Because we know what’s going to happen, the prom scene is quite boring. This is when the viewer will step out of the room to fill his drink. If this happens in a novel, the reader will put the book down and not pick it up again.

Additional Comment

Leslie: The 2013 film and the 1976 version are presented in a linear fashion with mostly standard cinematic POV. Both are different from the narrative device in the novel, which was epistolary and nonlinear.

Check out these posts to learn more about Point of View and Narrative Devices.

4. What are the Objects of Desire, in other words, wants and needs?

Valerie

Want: Carrie wants to belong and to be accepted.

Need: Carrie needs love and understanding from her mother.

Additional Comment

Leslie: In a Horror Story, the want (conscious object of desire related to the external genre) is usually to defeat the monster and save themselves and other victims. The need (unconscious object of desire) can be related to an internal genre, but it’s not required by the Horror genre, in which case, the need would be survival. Kim suggests, and I agree, that the internal journey for Carrie is Status-Pathetic, which would make the need something like changing her personal definition of success to avoid compromising her moral code.

Click here to learn more about Objects of Desire.

5. What is the Controlling Idea / Theme?

Valerie

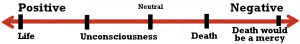

Both horror stories and action stories turn on the core value of life and death. However, while action stories stop at death, a horror story must go to the end of the line: the negation of the negation which is a fate worse than death.

Carrie spends her whole life in a fate worse than death. She is rejected by everyone, including her mother. Miss Desjardins is a possible exception, and Sue may be too. However, neither character is Carrie’s intimate friend. Instead, she is isolated and alone. She is a bullied teen, and as such, would rather die in the house with her mother than endure another day. For Carrie, death would be a mercy. This is perhaps what makes Carrie such an enduring story. Bullying has taken on a whole new dimension and cyber-bullying has in fact led to teen suicide; victims like Amanda Todd see death as preferable to the torment they’re forced to live through. This is perhaps the true horror of Carrie.

This is a story that ends negatively. While Carrie dies, the story starts and ends with the negation of the negation (fate worse than death). She was never accepted in life and will never be accepted in death (as evidenced by the graffiti on her headstone). She will remain an outsider forever.

Carrie is dealing with two obvious forces of antagonism: Chris and the girls at school (the bullies) and her mother (I would argue that she is the monster). Both reject Carrie based on their view of the world: what is right and what is wrong. Since Carrie doesn’t fit into either definition, she is rejected. Chris, the girls, and Margaret are all killed, but they too suffer a fate worse than death. Chris and the girls will always be remembered as the people who bullied a peer to the breaking point. They will always be culpable in the deaths of dozens of innocent people (other students and staff of the school). Likewise, Margaret’s soul is forever damned. She tried to murder her daughter and is a key factor in Carrie’s ultimate self-destruction. Interestingly, Margaret is also an outsider as is Chris (albeit to a lesser degree (the girls don’t side with her during the suicide-run scene)).

Therefore, the controlling idea is EITHER:

A fate worse than death results when society blindly adheres to a belief system that denies love and affection to individuals who are different.

OR

A fate worse than death results when we are denied love and acceptance and are forced to remain outsiders.

Additional Comments

Leslie: Here’s my take on this story: A fate worse than death results when a weak and naive protagonist lacks the guidance of a strong mentor, which they need to rise in social standing and to control the power within them.

Anne: Both tries at the Controlling Idea are excellent, both apply, and the difficulty we’re having in choosing one over the other is the whole problem with this movie. I might even go so far as to say that the fate worse than death here is to be made into a monster. “Society makes monsters of those it doesn’t accept.” It’s not to Story Grid spec, but I’d say that’s the cautionary tale here: “Be nice to people, you a**holes, or you’ll get your comeuppance.”

Click here to learn more about Controlling Ideas and Themes.

6. What is the Beginning Hook, Middle Build, and Ending Payoff?

Leslie

BEGINNING HOOK – Carrie gets her first period and is terrified by the experience while the other students mock her, and later mother, Margaret, accuses her of having lustful thoughts, but when her mother locks her in the closet to pray, will Carrie be able to control her gift? Yes, and her mother lets her out in the morning.

- Inciting incident: Carrie gets her first period and is terrified by the experience while the other students in her class, led by Chris, mock her and throw tampons at her.

- Progressive Complication/Turning Point: Carrie’s mother, Margaret, accuses her of having lustful thoughts in the shower and hits Carrie. Then she locks Carrie in a closet to pray.

- Crisis Question: Can Carrie control her burgeoning powers?

- Climax: Carrie cracks the door, but ultimately submits.

- Resolution: When her mother lets her out the next day, she tells her she’s a good girl..

- Inciting incident: Aguirre makes them come down from Brokeback one month early.

- Progressive Complication: Ennis is devastated when they part ways, both get married and have families, Ennis receives a postcard from Jack, and they comes for a visit.

MIDDLE BUILD – Carrie goes into a school bathroom after being taunted and is pleased when she can crack the mirror, and when she agrees to go to the prom with Tommy, Margaret tries to stop her, but when her mother threatens to tell Tommy about how Carrie was conceived, will Carrie be able to control her gift? Yes, though she takes control of the situation and puts her mother in the closet. Carrie and Tommy leave for the prom.

- Inciting incident: After being taunted by students in the school hallway, Carrie goes into the bathroom and breaks a mirror.

- Midpoint shift: Tommy convinces Carrie to go to the prom with him [after Sue tells him that it’s what she wants to make amends for what happened to Carrie].

- Progressive Complication/Turning Point: Margaret reacts badly when Carrie tells her that she’s going to the prom with Tommy and threatens to put her in the closet again. Then just before Tommy arrives on the night of the prom, Margaret reacts badly and threatens to tell Tommy about how Carrie was conceived.

- Crisis Question: Can Carrie control her powers again?

- Climax: Yes and Carrie chooses to take control of the situation and use her gift to lock her mother in the closet.

- Resolution: Carrie and Tommy leave for the prom.

ENDING PAYOFF – Carrie and Tommy go to the prom where Chris and her boyfriend Billy dump a bucket of pig’s blood on the couple, but when Chris drops the bucket and it kills Tommy, will Carrie be able to control her gift? No. She uses her gift to destroy the school, kill Billy and Chris, and ultimately kill her mother (after Margaret stabs her), but saves Sue, who is pregnant with a girl.

- Inciting incident: Carrie and Tommy arrive at the prom.

- Progressive Complication/Turning Point: When the election is rigged and Carrie and Tommy are elected queen and king of the prom, Chris and Billy dump a bucket of pig’s blood on Carrie and Tommy. Chris allows the bucket to fall on Tommy and kill him.

- Crisis Question: Will Carrie be able to control her gift?

- Climax: No. She destroys the school, hunts down Chris and Billy, and goes home.

- Resolution: After she returns home, her mother stabs her, and Carrie, unable to control her powers, stabs her mother with every other blade in the house. When Sue comes in, Carrie recognizes that she is pregnant with a baby girl and spares her life by sending her outside of the house while it implodes.

Additional Comments

Jarie: The other kids are so evil. Just like all the other 80’s teenage movies. Sue even feels guilty about it. Chris is the evil ringleader all that is wrong with society.

Click here to learn more about the Beginning Hook, Middle Build, and Ending Payoff.

7. Additional Story-Related Observations

Valerie: As already stated, it’s a great example of how narrative drive is used in a story.

Another great example of why it’s so important for the writer to pick a genre and stick with it throughout the story. Carrie is a classic horror novel, yet (in the DVD extras) the director, producer and star refer to it as a coming of age (ie worldview > maturation), thriller and science fiction story respectively. Also, while Carrie is considered a horror novel, does it still play as such for a modern audience? Writers need to figure out what story they want to tell, and then match it to the genre that will allow that story to shine. As a horror story, Carrie doesn’t seem to work well for modern audiences. BUT it’s an important story, and cyberbullying is a very important issue. Would it have been better to retell it as a society genre story? It would still have been horrifying, but not a horror. I know there are many considerations in re-telling a fan-favourite, but when writers are starting out and are writing original manuscripts, thinking about which genre will serve your story best is essential. Genre choice, is a vital choice.

A great example of how not to do a remake. Yes, Kim Peirce faced challenges from the production company, and in the end produced a film that was essentially a remake of Brian de Palma’s 1976 version. We saw the same issue with Jack the Giant Slayer, which was essentially a retelling of “Jack and the Beanstalk.” Stories that resonate with modern audiences have some element of the Society Genre in them; that is, issues that are relevant in today’s society. A prime example is Get Out.

Kim: Powerful example of inciting incident scene with shower scene. Also great innovation in Horror Genre for the victim and the monster to be the same person.

Anne: I see her as taking on the monster’s mantle only at the climax. She is monstrous towards her oppressors, a force of evil, killing people who were mean to her in horrific, torturous ways.

Leslie: This article suggests that the failure of the film to innovate is the fault of the studio executives who couldn’t say the word vagina.

Your Roundtable Story Grid Editors are Jarie Bolander, Valerie Francis, Anne Hawley, Kim Kessler, and Leslie Watts.

Join us again next time, when we disappear into the Thriller genre with Gillian Flynn’s 2014 hit Gone Girl. Why not give it a look during the week, and follow along with us?