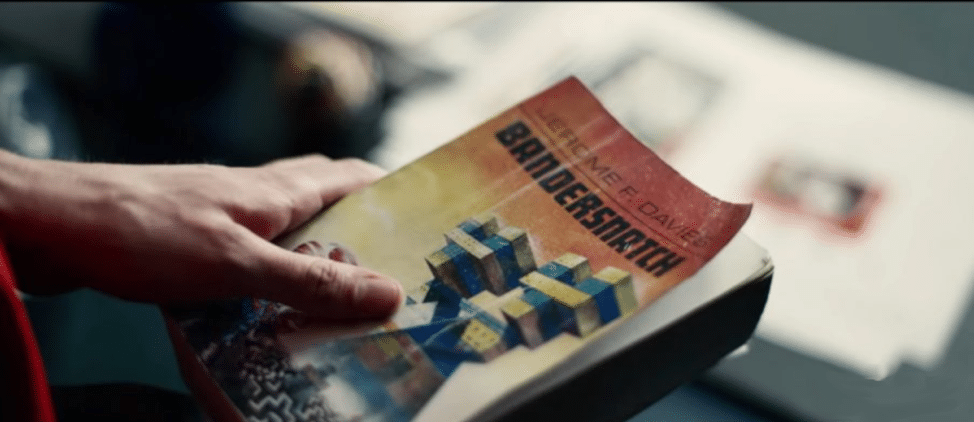

This week, Anne pitched “Bandersnatch” as a great test case for a complex story form. This 2018 episode of the Netflix series Black Mirror was directed by David Slade from a screenplay by Charlie Brooker. It’s a bit of a departure for us because it’s part TV show and part videogame, and we’ll take a look at how and whether it works.

The Story

Anne – Before I proceed, SPOILER WARNING. I don’t think any of us know for sure whether we saw all the variations and endings, but we’re definitely going to spoil the ones we did see.

Genre – I’m leaning towards Status on this one. The story is pretty fractured—by design—and a solid throughline wasn’t obvious, but Stefan, the main character, appears to be motivated by a desire for success or honor. He has a deadline and must perform. As far as I could tell on several attempts, the subgenre is either tragic or pathetic.

Now for the Beginning Hook, Middle Build, and Ending Payoff. I’ve done my best here, I really have. All I can say is, depending on which paths YOU follow in the game, your story may vary. Here’s my stripped down version.

- Beginning Hook – When Stefan’s pitch for a videogame is accepted by an up and coming game company, he must accept the job offer and all the perks, or insist on his own way of working by himself. He accepts the offer and the story ends in failure. Or, he says no and goes to work on his new game at home, agreeing to meet a difficult deadline.

- Middle Build – When Stefan loses his temper over a code failure, alerting his worried father to some mental health issues, Stefan must agree to visit with his therapist or else go off with his game Mentor Colin and solve his blockage another way. He goes with Colin, takes LSD, seems to watch Colin die by suicide, and wakes up as if from a bad dream, still facing the looming deadline. OR he goes to his therapist and relives the childhood trauma of losing his mother in a train derailment.

- Ending Payoff – When the LSD trip or else the therapy session leads Stefan to uncover a mind control conspiracy that has been using him all his life, or maybe a conspiracy in which Netflix in the future is controlling his actions, he must control his temper or else give in to the violent impulse that may be his own or may be inflicted on him from the outside. He controls his temper but destroys his own computer, the game, and his career. Or he kills his father and meets his deadline. The game is released to rave reviews because it’s that good. Or it’s released to mediocre reviews because it’s bad, but interesting because its creator is a murderer. Either way, Stefan is in prison for killing his dad.

The Principle

Anne – Honestly, I think “Bandersnatch” may be a case against complex story form. Valerie’s going to make the case that this isn’t a nonlinear story, but a basic linear one with a choice of which line to follow. I agree with that assessment, but it is a complex story because of all the possible threads. It’s complex to watch, and it must have been pretty complex to write.

But it’s not interesting as a story, and I think we’re all going to be talking about why.

First of all, it’s presented on that huge story-purveying platform Netflix, and is an episode of Black Mirror, which is an anthology series known for great storytelling. That setup, which is external to the episode itself, says this is going to be a story, and instead the episode tries to delivers a game.

It’s almost like picking up a book whose cover and marketing announce Thriller and it turns out to be a romance. Readers could be forgiven for feeling dissatisfied–romance wasn’t what they came here for. With “Bandersnatch,” if you came for a story, you got a game.

And if you came for a game, well, it’s not a very good one.

So I asked Google, “What’s the difference between a game and a story?” and the first hit I got was a marvelous article titled “Where Stories End and Games Begin,” by a guy named Greg Costikyan. He’s known as Designer X, a senior American game designer, and he is also the author of four science fiction novels.

The article is nearly 20 years old, so he isn’t writing specifically about “Bandersnatch,” but he might as well be. I’m going to quote a couple of passages.

Game designers need to understand that gaming is not inherently a storytelling medium…and that this is not a flaw, that our field is not intrinsically inferior to, say, film, merely because movies are better at storytelling.

He goes on to state that a story is linear–in that you experience it linearly, from first page to last or from opening scene to closing scene, and it’s the same every time you read or watch it. A game is nonlinear and it must provide at least the illusion of free will to the player. The game structure constrains what they can do, but they must feel that they have options, and if they don’t they become mere passive recipients of the experience. They aren’t playing anymore.

Here’s the money quote:

In other words, there’s a direct, immediate conflict between the demands of story and the demands of a game. Divergence from a story’s path is likely to make for a less satisfying story; restricting a player’s freedom of action is likely to make for a less satisfying game. To the degree that you make a game more like a story–a controlled, predetermined experience, with events occurring as the author wishes–you make it a less effective game. To the degree that you make a story more like a game–with alternative paths and outcomes–you make it a less effective story. It’s not merely that games aren’t stories, and vice versa; rather, they are, in a sense, opposites.

So essentially, Costikyan is saying choose one path or the other. Ha ha. Story or Game? If you pick story, then write a story. If you pick game, create a game. The paths will never meet again.

And that is the fundamental problem with “Bandersnatch.” It tries to be both, and ends up not much of either. Whether you enjoy it or not comes down to whether you enjoy the puzzle and exploration aspects and interacting with the “text”–or you prefer a complete story where your participation is limited to the act of reading or watching, and experiencing the story inwardly.

I need to make a disclaimer here: the last interactive quest type game I played was Myst, probably in the early nineties. So I’m not in the target audience for “Bandersnatch.” But who is?

If I were a gamer, I’m pretty sure this trip down memory lane to, basically, Zork with pretty pictures, would be fun once as a novelty, but it’s not challenging as a game, and I can’t see where I’d play it more than a couple of times.

Now, I like a complicated tale, but I like it to be delivered to me in a complete form. I want the author to have ventured down the various paths their story suggested, picked the one that best fit what they wanted to say in the genre they’re writing, and discarded all the others.

That’s their job. That’s OUR job as writers.

What I do like about complex story forms is their puzzle aspects, and “Bandersnatch” tries to present some of these, with the mysterious conspiracy story which may be arising from Stefan’s mental breakdown over his project, or from taking LSD. I could have gotten into a story like that, because there’s an interesting mental challenge to keeping track of the pieces, and doing some of the work of making sense of them. That’s a story I can reread or rewatch, combing through it for clues like a sleuth.

But unfortunately, it was so tedious to comb through Bandersnatch that I only got through it a second time because I had to for the podcast. It’s slow, you can’t pause and go back, you have to wait for the ten-second clock to elapse on every choice point. It got boring and annoying really fast.

The most puzzle-like story we’ve covered on the podcast is Cloud Atlas, and though I don’t think any of us loved the movie, the puzzle pieces of the novel it was based on revolved around engaging characters whose trials created pathos and whose triumphs were satisfying.

In “Bandersnatch,” there was so much energy on the branching paths that character development was shortchanged. I can’t say I cared much about Stefan, and when I made him choose one thing over another, he became kind of a hand-puppet instead of a human character–but one I couldn’t make do anything really interesting.

Game design and deadline pressures are driving poor Stefan out of his mind. Making a good choice for him, like, “No Stefan, don’t kill your Dad,” either ends the game or loops me back. I feel corralled into making Stefan into a murderer–the story fails if I don’t. Leslie’s going to talk about the uncomfortable impact of that in a minute. But it doesn’t make me care about the protagonist. It makes me want to exit.

From the Story Grid perspective, the crises don’t escalate properly. The first choice you make for the protagonist is between two breakfast cereals, and that choice has no impact on how the story proceeds. It’s there merely to train you in your new job as an interactive participant in the story. Near the midpoint, you choose which of the two characters is going to jump to his death, a powerful crisis. After that, you choose whether Stefan should bite his nails, which is back to the breakfast cereal level. The crisis point reversibility is all over the place, rather than steadily climbing.

If you make a so-called “wrong” choice, the story either stops or loops back, forcing you eventually to escape by means of the closing credits, or take it to its win but lose conclusion, where your computer game is a hit but you’re in prison for murder.

Is this the new thing?

The form’s been around in early computer games AND choose-your-own adventure books since the 1960s. If you’re interested, there’s a small niche community of people creating hypertext novels. The basic idea is that you explore the story, moving from one branch to another, gradually gaining an understanding of what’s happening. The stories come with their own software, and at present seem to rely on desktop operating systems.

Will we gradually subsume stories in games? I don’t think so. Both play and story are fundamental human activities, but they’re very different activities.

At a meta level, “Bandersnatch” might be seen as a story about the maddening nightmare of designing a story that works. The author of the big, thick paperback choose-your-own-adventure novel that Stefan is basing his game on went insane trying to get his mind around the branching structure of his story. He murdered his wife and presumably wound up in prison.

I’ll go right out on a limb and say that when you really break it down, “Bandersnatch” is a cautionary tale for writers and storytellers of all kinds. The meta-moral of the story is Keep It Simple. Choose your story and decide which crisis choice your character is going to make, based on the demands of the kind of story you’re telling. Let the other branches go. Edit them out.

And that’s my big takeaway as a writer: Nontraditional, non-linear, branching, hypertext, gamified … all these story forms are interesting and worthy of study. People who want to create a choose-your-own story should give it a go. Why not? We don’t all have to be mainstream.

But if that’s where your interest lies, design a game. Otherwise, be a storyteller, an author. Do your job and write a good, engaging, more or less linear story and deliver it to your audience fully formed.

Other Perspectives

Valerie

I agree with Anne that this isn’t really an example of non-linear story form. I wouldn’t even call it complex story form. Different, yes, but I’m not yet sold on it being complex. Having different paths to choose doesn’t automatically create a non-linear story. If you go down the wrong path, they rewind to the point you made the wrong decision and start again, but Stefan’s timeline is linear. They even put dates on the screen to show the passage of time.

And yes, there are options to choose from, so it’s tempting to look at the various flow charts online and perceive complexity. But anyone who has written, or is writing, a story (novel or screenplay) knows that this is the norm. The difference is that all these decisions are made by the writer in the privacy of the writer’s room, rather than by the audience. But do different options make it complex? I dunno.

I also agree with Anne that “Bandersnatch” is more of a game than anything else. It’s a novel idea, no doubt about that, but the more I think about it, the more I believe that as a story, it doesn’t work very well. That could be because the form is still in its infancy, but looking at this one example, in my opinion, the choose-your-own-adventure story annihilates narrative drive. Let me explain:

Narrative drive is all about creating a sense of curiosity in the audience. Viewers keep watching and readers keep turning pages because they want to know what will happen next. In theory then, the “Bandersnatch” style of storytelling sounds like it would be the perfect vehicle for generating narrative drive. In practice, it doesn’t. More precisely, it can’t sustain our interest or curiosity for long.

Because this is new, we’re initially curious about how the thing works. That gets us to tune in. As the story begins to unfold, we’re anticipating the first choice that we get to make. We’re asking, ‘When will it come? What will it be about? What are the consequences of the decision?’ We don’t really care about Stefan all that much. The seeds of a great story are there—we should be curious about the relationship between Stefan and his father—but we’re distracted by the game. We’re focused on ourselves and what we have to do! When we have to do something.

When we’re writing stories it’s challenging, yet essential, to get the audience to empathize with the protagonist. The audience has got to care about what happens to him; empathy is key for narrative drive. With “Bandersnatch,” our attention is on us. When do we get to make a decision? When do we get to play God? Stefan never becomes a character we relate to. He’s only ever our plaything; our avatar.

If the point of curiosity in a choose-your-own-adventure is, ‘what are my choices?’ and by extension, ‘what are the consequences of my choices?’ then the crisis moments need to be really good, and each decision must send the viewer/reader down a unique path to a unique conclusion.

This is a logistics and budgetary nightmare, and intellectually, I can understand why the filmmakers created some dead ends in the story. The problem is that these dead ends kill the narrative drive (no pun intended!). The whole premise of choose-your-own-adventure stories, is that we get to choose our own adventure. But in “Bandersnatch,” we don’t really. If we make the wrong choice, the game stops us and steers us down the path they want us to go. This only needs to happen once for us to lose interest in the story.

I’m not a gamer, so I wondered if my impatience with this true lack of choice was just me. (Maybe I’m not the demographic!) So, I asked my daughter to watch/play and her reaction was very similar to mine. The first time she was corrected, she cried foul. From that point on, she lost interest quickly. The second time it happened she started talking to the tv. “But, this is supposed to be my choice! Why did you ask me to choose if you’re going to do what you want?”

She kept wanting to leave the room and at one point she asked if she could turn it off. She stuck with it to help me but by the end she was examining her fingernails and I had to tell her that it was time to make a choice.

This is not a child with an attention problem. She can binge watch Stranger Things and barely blink. She can recite every episode of Friends and still laugh. Marta Kauffman is such a brilliant writer that the anticipation of the punch line of her jokes still works 20 years later.

I’ve been thinking about why this representation of choose-your-own-adventure is a problem and here’s what I’ve come up with: “Bandersnatch” does not use the 5 Commandments of Storytelling effectively. The turning points lead to a question, but it’s not a crisis question. There is no dilemma (Best Bad Choice situation or an Irreconcilable Goods situation)—there’s simply an option between two random things.

So the questions we’re asking ourselves switch from, ‘what does this option do?’ to ‘what difference does it make?’ or worse, ‘ how do I get out of this game?’

In some cases, there are no consequences to the climactic decisions. For example, it doesn’t matter which cereal is chosen, or which music is chosen on the bus. Other times, the game overrides our decision (like when Colin offers Stefan drugs) or, the decision leads to a dead end (like when Stefan choses to work in the gaming office). In the end, my daughter and I made different choices but the game wouldn’t let her quit until she ended up in the same situation that I ultimately got.

So, if there is no scenario in which Stefan’s game is a success or Stefan remains sane, then the choices the viewer makes are moot.

Leslie – Why We Study Stories, POV, and Crisis Questions

Why We Study Stories

“Bandersnatch” wasn’t necessarily an enjoyable story experience for me. I couldn’t slip into the narrative dream because I had to stay alert and make decisions, and those decisions left me feeling less than wonderful. But it was a great example of what stories can do. It also showed me what typical story elements accomplish by subverting them—because, I assume, “Bandersnatch” is meant to do something different from the typical story.

Although the narrative is linear, we get to call do-overs when we make a decision that doesn’t work out so well for Stefan (so much for irreversibility of character climax decisions). When writers alter structure in this way, they often want us to look at storytelling itself. But I don’t think that’s what the creators’ intended here. I’ll come back to this point below.

Valerie makes an excellent point that narrative drive isn’t really working, at least not the way it does in a typical story. I started out curious about what would happen, but that was altered when I was permitted to repeat decisions that didn’t go as well as I’d hoped. My concern for Stefan quickly eroded, beginning with the first story-focused crisis to accept or refuse the deal with Tuckersoft, because in that moment part of me realized the rules of this story world weren’t typical. It became more of a puzzle I wanted to solve (How can I finish the game and earn five out of five stars?) and less of a story. So my first “wrong answer” was an inciting incident that changed goal and therefore my entire approach to the story/game. I no longer cared about Stefan’s welfare, but I didn’t realize it until I faced the dilemma to chop up or bury a body. That’s both the genius and scary part of this story.

It reminds me of the 1961 Milgram experiment testing obedience to authority figures in which subjects were directed to administer electric shock to a student who gave the wrong answer in a memory recall exercise. If you compare that and the “Bandersnatch” episode with the studies (for example this one) that show reading fiction tends to make people better at empathy and understanding others, then you realize something other than a story is happening here.

I don’t think we get the benefit of several do-overs because the creator wants us to look at our own decisions and reassess in terms of what’s in Stefan’s or our own highest good. I think it’s much more likely that Netflix wants to look at our decisions with the goal of gathering the holy grail of data, clear choices tied to an identifiable individual, as opposed to an anonymous user. Is it any wonder this was set in 1984?

This is a great exercise and lesson in understanding that all kinds of people in the world understand story and use it to their advantage. Shawn has made the point more than once that we should study stories so we can tell better ones, but it’s also important that we identify the stories that are being worked on us. (For the record, I don’t think Netflix has intent other than commercial ones here, but again, it’s a great exercise in looking at the story beneath the story.)

Takeaway for the fiction writer: Use your powers for good not evil, and be aware of the stories you encounter in the real world.

Point of View

If you accept that the narrative drive in “Bandersnatch” comes from our desire win the game, then one way the creators accomplish this is with second person POV, which is the same employed in gamebooks, the most popular examples being the Choose Your Own Adventure series.

The important thing to understand about any point of view choice is that it’s not just a grammatical construct, and honestly, that’s not a useful way to make the decision. Think about it this way: When you choose a point of view character or narrator, you answer the question, who should tell this story, and what information do they have access to? When you choose the specific point of view (1st, 2nd, 3rd limited, omniscient), you’re answering the question, how should the character or narrator tell the story?

If you think of point of view like a camera’s viewfinder, you’re on the right track because POV choices, when combined with other writing tools, allow the reader to slip into the character’s skin or view the scene from far away in time and space.

Second person point of view can work multiple ways. It can pull the reader deep into the character’s perspective and experience, like first person masked as second person. Anne and I talked about this form in episode 126 of the Writership Podcast. In the submission we discuss, a character tries to persuade the reader to see things his way. But second person can also move in the other direction, to make the reader or viewer a stand-in for the character, like we have in the Choose Your Own Adventure stories and the “Bandersnatch” episode.

Either way, there is an immediacy that feels like reliving, rather than a retelling of events. Second person POV is often used in sales copy for this reason. The line between the character and reader dissolves. It’s an intense POV that can be overwhelming and off-putting, with little room for flexible narrative distance, and one that removes the typical protective frame the reader inhabits in relation to story events. But in the right circumstances and when executed well, this is a powerful tool.

Takeaway for the fiction writer: POV choices are not just tense and pronoun picks, so be aware of what you’re trying to accomplish and pick the POV that is most effective.

Crisis Questions

Because this isn’t a typical story and it’s not doing the things a typical story does, as Valerie explains, the crisis questions that we answer often don’t feel quite right.

Even when we reached the story-focused crisis of the beginning hook, to accept or refuse Tuckersoft’s offer, we don’t know what’s at stake or what the choices mean. The option that makes the most sense, and the one you would see in a typical Status story (accept the opportunity—there is no refusal of the call in a Status story), causes the story/game to end right away. So as I mentioned earlier, we learn that the rules of the story world aren’t what we think they are, so all bets are off, and soon you’re burying your father in the garden. EEK!

For purposes of this exploration, I reviewed an installment of the Choose Your Own Adventure (CYOA) series from my children’s library—Space and Beyond. It’s better than “Bandersnatch,” in that we see what’s at stake and the choices seem to actually matter, but the story lines are still thin. They might be more substantial than “Bandersnatch,” but at heart, they are still more game than story. All of this points to what Anne suggests is a continuum with story on one side, and games on the other. “Bandersnatch” is somewhere in the middle, and the CYOA books are a little closer to story. The genre within what I would call “true” stories that comes closest to CYOA are crime stories, and if you read “The Murders in the Rue Morgue,” by Edgar Allan Poe, with its opening discussion of the relative merits of chess and checkers, you can probably see the connection. If you’re really interested in skirting the game-story line, I found a site that uses images to show how the narrative is put together.

Takeaway for the fiction writer: If you’re writing a story with typical structure, your Crisis Questions should be best bad choices or irreconcilable goods choices, and the dilemma should in some way impact the life value of your global genre.

Kim

I had a lot of fun watching and interacting with Bandersnatch, not so much as a story but simply as a diverting experience.

Because amidst the variety of story threads, there aren’t really any significant setups and payoffs and no surprising yet inevitable conclusions. It all just feels pretty random, which is not a pattern we can find meaning in and so there can be no lasting satisfaction.

This is ultimately what seems to be missing for me: a meaningful story pattern–aka an identifiable genre. If there is a bonafide content genre, it doesn’t seem to be executed strongly enough for the meaning to hit home, or perhaps it’s just not the kind of story I enjoy.

Either way, knowing your content genre is the fundamental piece of information to tell a story that works. The number one reason a story doesn’t work is because global content genre is not well-defined.

Why is that, you ask?

The term “content genre” is really a stand-in for “life values at stake” which is not a fixed point but rather a spectrum of values from most positive to most negative/the negation of the negation (and all the possible gradations in between). Check out the post from me and Valerie, Simply Irreversible: Quantifying Progressive Complications

Depending on where are a story begins on the spectrum (positive or negative) and where it ends on that same range (positive or negative) tells us something meaningful about whatever happened in between. We can’t help but try to interpret some kind of meaning from it because humans are hardwired to find meaning. Whether or not the audience can interpret something meaningful is ultimately what makes a story work or not work.

So let’s step back and look at what makes a story a story.

For our in-depth work on internal genres, Leslie and I dug into the work of Norman Friedman and how he sought to distinguish narrative story and plot from other literary forms that had previously been lumped together.

His work centered on going deeper that just a “recital of events” that took place in a story, and instead honed in on the specific elements that create the pattern of meaning: (1) the protagonist’s character and motives, their state of mind, external circumstances (2) the change they undergo, and the (3) crucial chain of cause and effect leading them from one condition to another.

In the simplest terms, a story is: when a specific kind of protagonist is exposed to specific external circumstances and changes in a particular way, so that they are better or worse off than they are at the beginning of the story.

The combination of these elements is what provides the various prescriptive or cautionary tales we as humanity crave. And just to be clear, this definition of story applies to external genres as well as internal.

Let’s look at how these specific elements show up in Bandersnatch.

First we all experience the same opening: Stefan is a deep thinking and talented programmer, who takes medication and whose mother has died and now lives alone with his father who doesn’t seem to understand him. He is seeking to pitch and sell his complex game idea to a company in hopes of it becoming a mass market hit.

So that’s our set up. From here, no matter what path(s) you take, you will reach one of thirteen endings that are all negative: each ends in either failure of the game, Stefan’s death, or success for the game but Stefan is a murderer.

The greatest change we can track is Stefan’s external circumstances (his fortune/status) and each time it ends up worse off than he began. This indicates a Status-Pathetic or Status-Tragic story arc.

Status-Pathetic: When a sympathetic protagonist, who has weak character and is too unsophisticated to see the consequences of their actions, experiences misfortune without the guidance of an adequate mentor, they will fail to rise in social standing.

Status-Tragic: When a sympathetic protagonist, ambitious and sophisticated enough to see the consequences of their actions, lacks an adequate mentor and makes a serious mistake in their attempt to rise, the result is a tragic fall in social standing, and often death.

An argument could be made for either and perhaps it varies somewhat depending on the path, but either way our life values at stake are Success/Failure which point the Controlling Idea/Theme I am calling out for this story:

A protagonist is doomed to failure when they’re options are limited and controlled by a force other than they’re own.

This is a meta meta meta theme because it applies to the protagonist, Stefan, whose actions are forced by what we, the viewer, choose for him, and it apples to us, the viewer, as our choices are limited to what the game creator has laid out for us to choose from. It seems fitting that Stefan tells his therapist that the game he created only has the illusion of freewill. This sums up our viewing experience quite accurately.

And I think that is really why it bothers us.

In a typical story experience, the only element of control we have is whether or not to keep reading. But here, we are given the illusion of choice, so we think we have some control over the outcome. But we really don’t. I never chose for Stefan to kill his father, and yet he ends up doing it anyway at a later point without me being given the option. There was no way to “win”–all the endings are negative.

For me, the most satisfying ending was when he was able to go back in time through the mirror to when he was a child and choose to go with his mother on the train, which then turned out as if he’d died in the therapist’s chair. That, to me, was a beautiful ending with the greatest sense of empowerment to choose how the story ends–because he/we know what it means to go on the 8:45 train, and he/we choose it anyway. That is a choice that has true meaning even if it’s a bittersweet ending.

However, the rest of the story threads don’t provide this kind of satisfaction. (Because to be clear, just because a story ends at a negative life value does not mean it isn’t satisfying.) The other endings don’t seem to convey any specific meaning. Unless that too is part of the point? If there is a point? Is there meaning in acknowledging and recognizing that we only have the illusion of free will and something else is really pulling the strings? And does that make what seems random actually the opposite? Aka pure intention?

This may have all shifted to over-the-top meta nonsense, but when I step back and look at our modern lives and all the screens we’re plugged into, all the apps, etc, advertising and marketing in all its forms (Netflix, Google, Amazon, Facebook, you name it) and then I think that I am in control, that I am making free will choices…having this discussion today actually gives me pause to really consider if that is true. How much are we and therefore our choices influenced by these and other outside parties?

I always cite the quote “No one is an island unto themselves” when talking about story and life and how it’s all connected–how we are all connected. Usually I interpret that to be a beautiful and positive meaning.

In this context, I can look at Stefan’s fate and it becomes a clear cautionary tale for us all:

Because you are not not an island, because you are hopelessly connected, be aware (and beware) of the outside forces that are calling the shots on your options and your choices.

Listener Question

To wind up the episode, we take questions from our listeners. This week’s question comes to us from Matheus, who asks about the definition of internal and external charge.

Valerie – Matheus is asking about those external and internal charge columns that Shawn lists on the foolscap.

I’ve got a whole article about this on the Fundamental Fridays blog, called Value Shift 101, but I’ll run through it quickly here. I recommend you look at the article too though, because the answer is more detailed and I’ve got some examples there to follow.

In a nutshell, these columns track the story on a global level. Consider each of the 15CS (those are the scenes outlined on the foolscap) and FROM THE AUTHOR’S POINT OF VIEW determine whether, at that scene, the protagonist is closer to (+) or further from (-) her object of desire (that is, her external want and internal need). Closer to means a shift toward the positive, further from is a shift toward the negative.

If your story doesn’t have an internal genre, then ignore that column on the foolscap.

There’s lots of examples to study:

- Silence of the Lambs

- Pride and Prejudice

- first two seasons of this podcast: E6CQA for each of the 12 content genres (which is the foolscap)

If you have a question about complex story form, or any other story principle, you can ask it on Twitter @storygridRT, or better still, click here and leave a voice message.

Join us next time for another deep dive into the conventions of the Action subgenre as Leslie pitches 2018’s Action-Epic comedy The Spy Who Dumped Me. Why not give it a look during the week, and follow along with us?

Your Roundtable Story Grid Editors are Jarie Bolander, Valerie Francis, Anne Hawley, Kim Kessler, and Leslie Watts.