We all have one: a favorite detective.

Who hasn’t binge-watched episodes of their favorite detective show? Okay, maybe not everyone loves crime shows or will stay up into the pre-dawn hours reading an Agatha Christie novel; however, most of us can think of a crime show or book they’ve enjoyed.

What makes a good crime story? Is it the plot or the characters? Or is it a combination of both that leads to a truly great book/show?

At Story Grid, we believe in the importance of both the macro and the micro story. The macro story concerns the global genre (one of Shawn Coyne’s 12 story genres), and the individual scenes make up the micro story. In order to achieve both the macro and micro stories, you need both plot and characters to achieve this structure. They go hand-in-hand and together form the works of a great novel.

In a crime story, the master detective character or other characters are as important as the crime itself and how the murderer did it.

This is especially true if you are writing a detective series. Why? One of the main pros of writing a series is that readers can fall for your characters. This is one of the reasons why cozy mysteries (and other types of mysteries) are so popular. Readers (and viewers if you are writing screenplays) will want to come back and be enchanted not only a new mystery but also about the characters that they have grown to love. That is one of the benefits of great storytelling.

So how do you accomplish this?

In this article, I will go over how to craft a master detective for your story. However because the world of stories is so vast, I will focus this article on the Story Grid Crime Genre and the murder mystery subgenres.

Let’s get started.

What’s the Crime Story?

Shawn Coyne’s recent book Four Core Framework is a wonderful addition to your writing library. Another excellent reference tool for writing crime novels is fellow Story Grid Editor Rachelle Ramirez’s article, Secrets of the Crime Genre: How to Write a Great Caper.

In the article, Ramirez writes: “The Crime Story is an arch-plot (Hero’s Journey) or mini-plot (multiple characters) external genre. It begins with a crime, builds with an investigation or completion of the crime, and pays off with the identification of the perpetrators or their escape from identification. It is resolved with the perpetrator/s being brought to justice or getting away with the crime.”

After romance novels, mystery novels are the top story in the publishing world. People read mysteries because they want to be intrigued. They want to see the murder caught and brought to justice. (Please note: I am only going to discuss the Murder Mystery Genre and the subgenres. The Crime Genre also concerns the subgenre of organized crime. You can read more about it Ramirez’s article here). Let’s dive into the Global Crime Genre’s Global Value and the Core Need.

The Crime Genre’s Core Need

Shawn Coyne often talks about the Story Grid: Gas Gauge of Needs. This was inspired by a theory created by psychologist Abraham Maslow. Maslow created the idea to specifically look at the drivers that force people to act a certain way.

In “Discover Your Story’s Core,” Story Grid editors Anne Hawley and Leslie Watts write the “Core Value is the essential yardstick of your story. That famous red and blue graph on the cover of The Story Grid literally has Core Value as its Y-axis. It’s the metric of how high is high and how low is low.”

In the crime genre, the core need is safety. This core need arrives when the moment of the inciting crime in your story is discovered. For example, it would be the of a dead woman’s body or kidnapper’s note. In master detective stories, the world’s order has been upset, and security has been threatened. Someone has been murdered. The master detective wants to find out why. His or her job is to find out who did it and bring that person to justice.

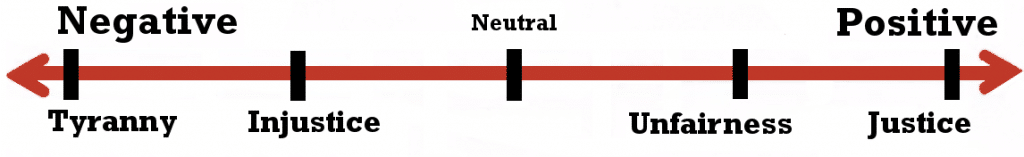

Your character’s safety has been thrown into a world of chaos, and it is up to your detective to figure out the puzzle. The core value (the Y-axis) will go along the lines of Justice, Unfairness, Injustice, and Tyranny.

The Core Event of your story is when the detective expose’s of the criminal. Every event in your story leads up to this moment.

Who is the killer?

Will they be brought to justice?

So, how does your detective solve the crime? How do you craft a detective that readers will want to follow? Let’s look at some of the traits a lot of crime solvers have in common. But first, we will take a look at the subgenres that form the murder mystery.

Subgenres of the Murder Mystery Genre:

The murder mystery genre has several subgenres.

The Master Detective: A mystery story where the protagonist is an experienced and brilliant sleuth.

- The Adventures of Sherlock Holmes, Sir Arthur Conan Doyle.

Cozy: This is the subgenre where the detective is an amateur, please think of the Hallmark movies that they have on TV. The amateur usually has a day job or a niche hobby such as knitting or cooking. Examples include:

- The Hannah Swenson series, Joanne Fluke

- The Aurora Teagarden series, Charlain Harris

Historical: A mystery story that takes place during a historical time period.

- Cadfael series, by Ellis Peters

- A Devil in the Marshalsea, by Antonia Hodgson

Noir/Hardboiled: A gritty series that deals with sex and violence in an unapologetic way. Most of the protagonists are oftentimes tragically flawed.

- The Shanghai Moon, S.J.Rozan

- The Maltese Falcon, Dashiell Hammett

Paranormal: The crime story has elements of magic and usually fantastical elements such as vampires and ghosts.

- The Dresden Files, by Jim Butcher

Police Procedural: The protagonist belongs either to a government agency (FBI, CSI, etc.) or a local agency (state police, police, sheriffs).

- CSI: Los Vegas, TV Show.

Let’s now look at some of the traits of a master detective!

A Strong Sense of Justice

Every master detective has to have a strong sense of justice in order to want to bring people to justice. Ask yourself, why did your detective decide to go after murderers? What made him or her wake up one day and decide that they wanted to spend the rest of their life (or working career) solving brutal crimes?

The answers to these questions are often found in your character’s backstory. You need to figure out how your detective is wounded. Everyone is wounded. We all have scars from our past. There have been moments in our life where people or certain situations have hurt us.

For example, someone who lived during the Depression Era might feel uneasy about spending money because they grew up with very little and had to “make due.” A person cheated on in a relationship might be wary about getting into another relationship, even if they desire one. Someone who had experienced being homeless might be worried about the possibility of it happening again.

These examples are emotional wounds that your characters could have. However, there are many others.

I’m not suggesting that you need to have every character have big emotional wounds or a tragic backstory, but everyone is afraid of something either subconsciously or consciously.

In the hit TV series Monk, Adrian Monk’s emotional wound (besides Monk being extremely OCD and scared of everything including milk) was that his wife, Trudy, was murdered in a car bomb several years before. Until the last episode of the series, Trudy’s murder is never solved.

Throughout the series, Monk is seen to be incredibly emotional and committed to a case when it involves a woman. Why? The murder of his beloved wife, Trudy, is what drives Monk to put people behind bars.

The world that Monk lives in is filled with injustice. His wife’s murder remains unsolved. He can’t figure out who murdered her, and he can’t put his wife’s killer behind bars. Monk can help the San Francisco police solve other murders and help bring those killers to justice, but that’s not the murder he wants solved.

Monk wants to solve his wife’s murder.

Monk has to wait until the end of the series to solve his wife’s murder. Until then, he has to settle bringing justice to other cases.

Ask yourself, why did your character want to solve crimes? Is it because of something that happened in your character’s past? Or is it because your character has a very protective instinct? Was someone in his or her family a cop beforehand?

Being very Smart

Master detectives are smart; they have to be in order to solve crimes and catch murderers. But is there a thing as being too smart?

Sometimes, your master detective is too brilliant. They are one step ahead of everyone else. They see too much. They already know who the murderer is before the end of chapter 2, and then the question comes to how do they prove it?

This is seen in Sir Arthur Conan Doyle’s Sherlock Holmes series. Sherlock Holmes is described as the smartest man who has ever lived. He’s also very eccentric. He frequently knows who the murderer is and why they did it before the reader has gotten past chapter 3.

For most of the Sherlock books, Dr. Watson acts as the narrator in the books. One of the reasons for this is that Sherlock is beyond intelligent, and most readers won’t relate to him. He’s eccentric. Sherlock’s oddball character might turn off some readers, whereas Watson’s character is more “normal.”

The two make a good pair and have become an iconic dynamic duo that solves crimes both off-screen (novels) and on-screen.

How does your character see things other people do not see? What are their unique gifts? Detectives are very observant.

What made your character that way?

In the TV series, Psych, private investigator Shawn was raised by a father who would train him on being a detective. His father would train Shawn on how to run from a kidnaper and how to escape from a car.

Dectectives are knowledgeable. This leads to the third trait.

Be an Expert in Another Field

Another common trait of a master detective is that they are knowledgeable about several different fields. This doesn’t mean that they have multiple doctorates and can build bombs.

The detective’s knowledge about a particular area of expertise helps them solve crimes. For instance, a person’s knowledge about baking might help them solve the murder.

This is the case of Joanne Fluke’s Hannah Swensen’s murder mystery series. Hannah is a baker, and often her skills as a baker help her uncover various crimes.

What knowledge does your detective have? Where did they acquire their knowledge?

Don’t be afraid to add humor. Often, comedy is said not to belong in mystery novels. However, it’s all about striking a balance. It’s a tricky balancing act, but once accomplished, it can lead to massive success. Some books that have done this well are:

- Dangerous Davies: the Last Detective, by Leslie Thomas

- The Charles Paris Mysteries, by Simon Brett

- One for the Money, Janet Evanovich

- The Chinese Agent, by Michael Moorcook

- Metzger’s Dog, Thomas Perry

- Skin Tight, Carl Hiaasen

- The Mordida Man, Ross Thomas

- Among others.

A Misunderstood Outsider

People don’t always understand each other. If your protagonist is eccentric (like Sherlock Holmes), he or she may be misunderstood.

In the hit TV-series Monk, the main protagonist was very misunderstood, and the police didn’t want him to interfere. A lot of people even made fun of him. Yet, he had a knack for solving crime. The mayor really liked Monk, so Monk received a chance to start working with the police.

What makes your detective operate outside of the realm of conventions? Do people think he or she is odd? Are they part of the police force? Or are they a private detective?

The Trouble with the Law

Not all of your characters have to like one another. A great source of tension for your novel can be when your protagonist is going up against higher authorities like a police chief or their boss. Or maybe your character is a private detective, and they are going up against the local law.

Some possibilities could be the local police chief throwing the private investigator in jail for tampering with the investigation after being warned to stay away. This is a common trope in crime fiction. An example of this is the BBC hit TV-show Father Brown, where the titular character Father Brown gets into trouble with the local inspector for interfering with the investigation. The TV-series is adapted from G.K. Chesterton’s The Father Brown Short Stories.

Their Work Partner is the Complete Opposite.

Opposites attract, and when you have characters that are the complete opposite of one another, it can set-up the reader for a good laugh. One of the best oddball pairings is the 1965 play The Odd Couple, by Neil Simon. The plot revolves around two mismatched roommates: Felix Ungar and Oscar Madison. Madison is easygoing, and to say it bluntly, a slob. Felix is neat; but too uptight.

These two characters became a dynamic comedic duo. This play went on to being a TV-show, a sitcom, and several film adaptations. While this isn’t a mystery series, it shows the power of a dynamic duo and comedy potential.

Another famous dynamic duo is Sherlock Holmes and Dr. Watson. However, Sherlock and Watson aren’t total opposites; and they do get along better than Felix and Oscar. Watson and Sherlock become very close friends. They consider each other to be a part of their family.

They are a Mystery

Let’s face it, master detectives can be odd ducks, and that’s okay. Not all of them are, but some are unique. Not everyone can solve crimes or murders. People don’t have it in them. I know I don’t, but what’s fun about reading mysteries is that frequently the master detective can be a mystery as well. No one knows what exactly makes him or her tick.

You should ask yourself if you want to make your detective a little bit of a mystery. This will often work when the narrator of the story isn’t the detective, but a sidekick like Dr. Watson.

The Internal Arc in Crime Fiction

Honestly, you have several different internal arcs that you can pick from. The most popular internal genre is romance.

As I’ve said earlier, romance books are the top category books globally and sell far more copies than any other genre. Mystery and Crime is the second favorite genre.

Often, authors will write mystery-romance novels. These novels are popular and are jam-packed with both the Story Grid romance and crime genres.

When you write a novel, you need to build it in layers. You can do it in multiple ways through the Worldview or the Morality Genre or something else.

Let your imagination run wild. Again, some helpful pieces of literature to read for further study are:

- Four Core Framework, by Shawn Coyne

- Discover Your Story’s Core, by Anne Hawley and Leslie Watts

- Secrets of the Crime Genre: How to Write a Great Caper, by Rachelle Ramirez

Another great read that will help you with emotional storytelling is:

- The Emotional Wound Thesaurus: A Writer’s Guide to Psychological Trauma, Angela Ackerman and Becca Puglisi

- The Emotion Thesaurus: A Writer’s Guide to Character Expression, by Angela Ackerman and Becca Puglisi

So What’s Next?

Read.

Honestly, the best advice I can give you is to go pick up a masterwork in the crime genre and read it. Please, pick up a dozen masterworks, read them, study them and pick them apart.

Shawn always tells us to read “widely and deeply.” He’s not alone in that thinking. Most authors I’ve talked to all state the importance of reading. Reading expands the mind and builds empathy. It will also help you learn how to write dialogue, showing vs. telling, description, and writing flawed but beautiful characters. Reading teaches you how to write, and it can even help you with brainstorming for your novels.

I wish you the best of luck with your novel and hope you are doing well. Take care, and happy writing and reading! – Victoria