I’ve been mulling over the ins and outs of cause and effect relationships in story for quite a while. But the power of how a deep understanding of causal relationships can improve stories came together for me in a strange context: The Great British Baking Show. I’m not a baker, but I love to watch the participants overcome challenges and hear honest and useful feedback from the masters. It’s a guilty pleasure, but also instructive. One thing I’ve noticed is that the bakers who do well consistently, whether they have experience with a particular baked good or not, are the ones who understand which ingredients and methods produce which flavors and textures. They understand the principles of baking in terms of causes and effects.

Causal relationships are just as important for storytellers.

Devoting time to the ins and outs of cause and effect relationships in stories will pay huge dividends and help you better understand the elements of the Story Grid methodology.

As Dwight V. Swain wrote, “Word photography isn’t enough.” And John Gardner explains we “must present, moment by moment, concrete images drawn from a careful observation of how people behave, and we must render the connections between moments, the exact gestures, facial expressions, or turns of speech that, within any given scene, move human beings from emotion to emotion, from one instant in time to the next.” A random series of interesting events does not necessarily create a great story.

What makes this such a challenge? Though we writers tend to read an awful lot, the narrative dream of a story can sweep us away so that we overlook the mechanics of creating a satisfying experience. When we read a great book and think, I want to write a story like this, the cause (knowledge, skill, and work) for the effect (a great story) is not apparent to us. Causal relationships within stories aren’t taught in typical creative writing courses, so many early efforts consist of chains of events that may create a beginning, middle, and end, but don’t include a causal thread to form a cohesive whole.

The stories readers enjoy most are the ones with clear causal connections that move from beginning to end, and are present from macro to micro. To write better stories, you can plan, draft, and revise with these relationships in mind.

Stories Are about Change

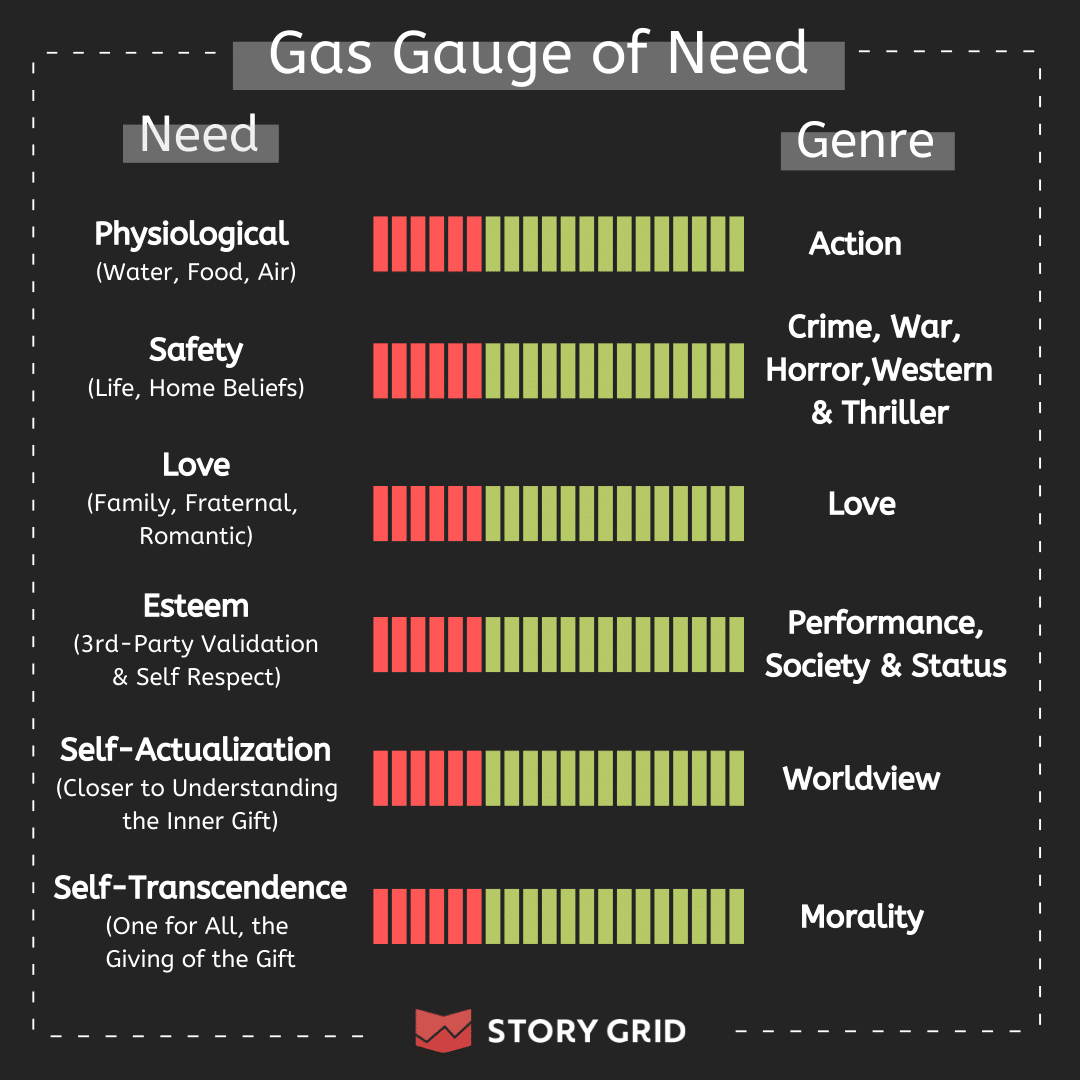

You can’t hang around the Story Grid community for long without hearing that stories are about change. The protagonist begins in one state or condition and ends the story in another. You’ve probably also heard that the change isn’t random. Instead, the state or condition that shifts—what we call life values in Story Grid parlance—connects your story’s content genre to our basic human needs.

Change within stories doesn’t happen by lightning strike. Life value shifts unfold over the course of the story, though we see bigger shifts at major turning points, for example in the scene that contains the global story turning point. We create this gradual change by combining a specific set of conditions and a series of causally related story events—causes and effects—arising from conflict and action.

A random set of events is of little interest to most readers. Even though, or maybe because, life is a chaotic mess where events seem to happen for no reason, readers demand that stories make sense, and cry foul when they don’t. We go to stories to help explain things we don’t understand and to learn valuable lessons without putting our own human needs on the line.

Of course, this doesn’t mean there has never been a commercially or critically successful story that failed to include a clear cause and effect thread. But if your goal is to write a great story, set yourself up for success by learning how the vast majority of great stories work, rather than focusing on anomalies.

Let’s take a look at conditions, causes, and effects before we see how they operate in a specific example.

Conditions

Before a cause can produce an effect, the conditions to make it possible must exist within the environment. If you want to bake croissants, you’ll need the ingredients, an oven, some other tools, and at least a basic idea of how to proceed. The conditions for a certain life value change should be present in the story or scene in the same way, but what does that mean?

During the Level Up Your Craft course, Shawn shared the term irrelevancies, the people, places, objects, and events existing within the near or distant environment that create the potential for unexpected events. These story details appear irrelevant at first glance, their significance only becoming clear in a critical moment. He used this term in the context of the progressive complications, but we can use the same concept to lay the foundation for our causal story thread.

On the global story level, the conditions needed to create a specific life value change include protagonist’s status quo or the ordinary world, as well as the global genre conventions: certain characters, setting, and means of turning the plot. The protagonist’s global objects of desire, or their wants and needs related to the global genre, enrich the environment as well.

Proximate Causes

Besides creating the necessary conditions or potential for a particular effect or result, a proximate or immediate cause must happen to kick things off. Those croissants will never be made if the baker doesn’t combine the ingredients, but of course, that’s just the start. The baker must knead and shape the dough and put it in the oven. A series of causes and effects, some of which will be unexpected because life often doesn’t go to plan, will transform the separate ingredients into the finished product.

On the global story level, the proximate cause of the change in life value is the global inciting incident, but every other scene should contribute to the story’s resolution by shifting the life values incrementally.

Effects

In real life, sometimes the relationship between cause and effect is obscured by a gap in time, or by something we don’t understand. For instance, if the baker doesn’t understand how to layer butter with their dough, they won’t see the proximate cause of a lack of layers in their finished croissants.

In stories, effects generally need to be clear and immediate. The big, global life value shift should occur over the course of the whole story, but it must be the result of micro causes and effects within the smaller units (subplots, acts, sequences, scenes and beats). What each cause means and why it matters should also be apparent to the reader, explicitly or implicitly.

Sometimes we want to withhold certain effects or what they mean from the reader, but you want to know what’s really going on. In early drafts, the best course is to write the effects clearly into the text and then remove what you are trying to cover up. You might also track them in a special column within the Story Grid spreadsheet.

Cause and Effect and the Story Grid Tools

Cause and effect are baked into the Story Grid tools, so understanding the former can help you understand the latter and vice versa.

The global Five Commandments of Storytelling provide a high-altitude view of the story. The inciting incident is the proximate cause that leads the protagonist to pursue a goal (effect). As they pursue their goal (cause), they encounter progressive complications. From the protagonist’s perspective, these can be both the effect of their earlier action (response from the force of antagonism) and the cause for their next action. The turning point progressive complication is the effect of the character’s final attempt to reach the goal using their initial strategy and what gives rise to the dilemma they face in the crisis. The climax is the protagonist’s resulting decision and action that causes the resolution.

As you change altitude from thirty thousand feet to ground level (from global story to acts, sequences, scenes, and beats), the causes and effects grow smaller but follow the same pattern and contribute to the overall story because the effects shift the global life value.

Similarly, obligatory scenes are a series of genre-specific causes and effects that help you meet reader expectations. You can also look through the lens of the Eight Fundamental scenes (hero’s journey), virgin’s promise, or other archetypes as applicable.

Once you understand the specific global change you want to create in your story, you can begin to imagine the micro causes the readers of your genre expect. Every unit of story should contain the conditions, proximate causes, and effects necessary to support the global value shift.

What are scene conditions, proximate causes, and effects?

Scene conditions include the story events that have come before, but also include more micro, specific conditions: the characters, setting, and objects that make the proximate cause possible. An important aspect of the conditions is the essential action or the POV character’s scene goal expressed with an active verb. This is the scene equivalent of the global objects of desire.

Once the conditions have been established in the scene, the inciting incident (a proximate cause) creates a desire and goal for the POV character to arise (effect). As they pursue the goal (cause), progressive complications arise (effects and further causes), in a dance of action and reaction, moving toward the turning point progressive complication, crisis, climax, and resolution. Again, each scene commandment is an effect of what has come before and a cause for the next commandment.

Cause and Effect in Action

In theory, this all sounds good, but how about in practice? Here’s how cause and effect operate in Treasure Island, the Story Grid Edition I’m working on. Robert Louis Stevenson’s beloved tale combines an external Action-Duel-Hunted story with a Status-Admiration internal genre. (Note: I’ve gone around and around on the internal genre of this story between Status and Worldview Maturation [and probably will continue to do so]. Treasure Island is often listed among coming of age or bildungsroman stories, and Jim’s thinking certainly becomes more sophisticated over the course of the story. But as I see it, the internal change that impacts the global story the most and how he outwits the villain is related to his definitions of success and compromise. I welcome your thoughts on this point.)

When the story opens, young Jim Hawkins works and lives with his parents at the Admiral Benbow Inn near the southern coast of England. The pirate Billy Bones seeks lodging with them, and soon several dangerous pirates come looking for the treasure map he keeps in his sea chest and threatening Jim in the process. When Bones dies, instead of giving the sea chest to the other pirates, Jim thinks he can outwit them to keep the map for himself. He has a close escape, but the hunger for adventure awakens within him. With the treasure map, Jim, Dr. Livesey, and Squire Trelawny hire a ship, captain, and crew then set sail from Bristol to seek the treasure. Jim and his friends don’t realize the majority of the crew are pirates, led by Long John Silver, and that they intend to kill the others once the treasure is safely aboard. Jim discovers the plot, but by the end of the story, only five of the original crew members return to Bristol and Silver escapes en route. Though Jim is alive and possesses a great fortune, he now sees adventures as dangerous enterprises and no longer wants any part of them.

The life values at stake in an Action story are life and death, and the values for a Status story are success and failure. Through the story, Jim’s external situation moves along the spectrum from alive and safe to injured to threatened with death. Internally, he moves along the spectrum of failure, compromise, and success. If we view each life value shift as an effect, we can immediately think of possible causes that would produce them.

Controlling Idea/Theme

When you understand the cause and effect for the life value change of your story, you have a great tool to help you plan, draft, and revise it. The controlling idea/theme distills the entire story to a statement expressing the climactic life value change, whether it’s negative or positive, and the specific cause of the change. Simple enough, but how do you craft a controlling idea statement? Here’s a handy template:

[Global life value at stake] + [verb expressing positive or negative result] when [particular type of protagonist] + [cause of change].

This is the typical controlling idea for an action story with a positive ending:

Life is preserved when the protagonist overpowers or outwits their external and internal antagonists.

You can use the typical controlling idea to get you started, but you’ll want to customize it for your story. The clearer you can be about who the protagonist is and how they overpower or outwit their antagonists, the better. When you have an external global story like action paired with an internal genre, the way the protagonist prevails or fails should be related to the internal life value shift. The internal genre contributes the subconscious object of desire, or what the protagonist needs to overcome the external force of antagonism. Let me show you what I mean with an example of my working controlling idea statement from Treasure Island.

Life is preserved when a young adventurer outwits the pirates by recognizing that his moral code isn’t compromised by joining forces when their interests align.

Sometimes reframing the controlling idea makes it more clear. Here’s another template with the Treasure Island example following:

When a [specific type of protagonist] + [cause of the change], [positive or negative life value] + [verb expressing positive or negative result].

When the young adventurer outwits pirates by recognizing that his moral code isn’t compromised by joining forces when their interests align, life prevails.

Your controlling idea will likely change over time as you gain a deeper understanding of what’s at work in your story. You may not be certain at the outset how the protagonist will prevail, but even if you only use the typical controlling idea for your genre, you’ll still have a better understanding of the change you need to create over the course of your story and your subconscious mind will be working on it even when you’re not at your writing desk.

Conditions and Conventions

Genre conventions are the conditions related to character, setting, and means of turning the plot, you need to set up reader expectations. They create the ideal environment for the specific life value shift. In Treasure Island, you’ll find the conventions for the Action-Duel Hunted Plot. Because the story includes an internal genre to go with the global action story, the conventions for Status are needed for the cause and effect of this story.

Characters or roles

- Well-defined hero, victim, and villain: Jim is the primary hero, and he and the honest crew members are the victims of the villainous pirates, led by Silver. (Action)

- A strong mentor figure to help the protagonist avoid violating their inner moral compass as they seek to rise within society: Dr. Livesey (Status)

- The herald or threshold guardian, a fellow striver who sold out: Silver (Status)

- Shapeshifters as hypocrites are secondary characters who say one thing and do another. Similar to the herald, these characters compromise or sell out in pursuit of their definition of success: Silver (Status)

Setting

- Big social problem. This provides a context for conflict and the opportunity for the protagonist to consider compromise or selling out: Limited access to the means to make a legitimate income. (Status)

Ways of turning the plot

- The hero’s goal is to stop the villain and save the victims: Jim’s clear goal, from the moment the danger is apparent, is to save himself and the other innocent crew members. (Action)

- The power divide between the hero and the villain is very large: Silver is a violent pirate leading a crew of other pirates, and more savvy than Jim. He possesses secret plans, as well as the power of persuasion to convince people to join forces with him. Jim is a young, inexperienced adolescent with little experience with weapons. (Action)

- Speech in praise of the villain: Bones, Ben Gunn, and Jim himself let us know that Silver is a terrible force to be reckoned with. (Action)

- Specific to the Hunted plot, we see shifting alliances in which the hero sometimes joins forces with one or more of the antagonists where their interests align. (Action)

- A clear point of no return/truth will out moment: Jim must decide whether to honor his word to Silver that he won’t try to run when Livesey encourages him to (remain steadfast or compromise his moral code), knowing another opportunity to escape is unlikely. (Status)

- A win-but-lose or lose-but-win ending: Jim changes his definition of success. Though romantic in theory, in reality adventures are dangerous. He has suffered, feels guilty for the people who died, and has no interest in returning to Treasure Island, though the balance of Flint’s treasure remains there. (Status)

By setting up characters with opposing goals, strong motives, differing means of obtaining success, and a huge power difference, we create the conditions for a life and death struggle in the pursuit of material success, that could end well—or not. These conventions create the potential for proximate causes throughout the story.

A Series of Causes and Effects

Here are the fifteen key scenes from Treasure Island to give you an idea of the causes and effects that bring about the global story value changes.

Beginning Hook

- Inciting Incident: Bones arrives at the Admiral Benbow Inn, which draws the pirates who want the map.

- Turning Point Progressive Complication: Bones dies of a stroke, and the pirates want Jim to give up the map.

- Crisis: Jim must decide whether to give the pirates the map or try to outwit them.

- Climax: Jim keeps the map, seeks help, and hides to avoid the pirates.

- Resolution: One pirate is killed, and the others run. Jim, Dr. Livesey, and Squire Trelawny decide to pursue the treasure.

Middle Build

- Inciting Incident: Jim and the others set sail, but he learns that Silver is a pirate and with his crew intends to kill the others once the treasure is on board. This causes Jim and his friends to form a plan to abandon the ship and hole up in a stockade on the island.

- Turning Point Progressive Complication: On an outing from the stockade, Jim discovers that only two drunk pirates guard the ship.

- Crisis: Jim must decide whether to inform the adults or try to outwit the pirates on his own.

- Climax: Jim decides to retake the ship by himself.

- Resolution: Discovering one pirate already dead, Jim guides the ship to a safe place then outwits and kills the other pirate. When he returns to the stockade, he finds it in the hands of Silver and the other pirates.

Ending Payoff

- Inciting Incident: Jim is captured by the other pirates but negotiates with Silver to stay alive by promising to speak up for them with the British authorities. He learns his friends abandoned the stockade and gave Silver the map.

- Turning Point Progressive Complication: When the pirates seek the treasure, they find it’s missing and turn on Silver.

- Crisis: Jim must decide whether to join forces with Sliver or not.

- Climax: He decides to join Silver against the other pirates.

- Resolution: With the help of Dr. Livesey and Ben Gunn, the rest of the pirates are killed or running for their lives. Jim and his friends take as much treasure as the ship will carry and head for Bristol. Silver escapes during a stop for provisions.

Cause and Effect Within Scenes

Scenes are smaller units of story, but they operate in the same way on the micro level. I’ve provided a specific scene example from Treasure Island to show the conditions, causes, and effects on the micro level, which you can download here.

Using Cause and Effect

Many of the Story Grid tools were designed with revision in mind, but cause and effect is one that is useful before, during, and after drafting your story. No matter what phase you’re in, if you have a good understanding of the cause, you can use it, along with the conditions for your genre, to solve for the effect—and vice versa.

Cause and effect is useful for planning your story because it helps you understand how the character gets from point A (beginning life value) to point B (ending life value). You could drive yourself crazy by going too micro during the planning stage, so find the level of detail you need to write your draft as quickly as you can. Some writers work from a detailed outline, and might want to draft a cause and effect sentence for each scene. Others might want to draft the cause and effect statements for the obligatory scenes or the fifteen key scenes. There is no one right way to do it, only the way that best supports you in completing your draft.

When you’re in discovery mode, make lists of conditions, causes, and effects involving your characters and story world. Also, gather interesting causal relationships from the stories you love. This will help you while you plan, but also give you great fodder for drafting and revision.

While drafting, if you get stuck, use what you know and have written so far to solve for what you don’t know. For example, you’ll know the conditions you’ve created or the conventions and story events to the point you’ve written, and you may know the inciting incident for my next scene. Imagine several different options that might result, or pull one from your discovery list. Similarly, if you know the result you’re looking for, consider what conflicts and action might produce the result.

In the revision phase, I recommend moving from the macro to the micro to assess your story for a clear cause and effect progression. You could include a separate column in your Story Grid spreadsheet to track this scene by scene if it makes sense for you.

Typical problems to look for include:

- Causes without effects

- Effects without causes

- Cause and effect out of order

- Unclear meaning of cause or effect

Once you identify these problems, you’re well on your way to solving them, but you need to know they exist first.

Don’t let this analysis become a vehicle for resistance, though. We can get lost in the analysis so that we finish. Go as far as you need to solve your immediate problem, but return to your writing. You can’t improve a story with your new understanding of cause and effect unless you have a story.

Final Thoughts

Since you’re here on the Story Grid site, I’m going to assume you want to write a great story. Your goal is a story that keeps readers spellbound, delighting or disturbing them as appropriate, whose characters and events linger in the mind long after the end. I suspect you also understand that it takes effort, and you’re not afraid to roll up your sleeves and do what it takes.

But because you’re human, I also know that your time is limited. Lots of people, places, and things compete for your attention, which is also limited. You want to make the most of the time, energy, and focus you have. Understanding cause and effect relationships will help you better understand the elements of the Story Grid methodology so you can write a better story.

Big thanks to Anne Hawley for reviewing this article and offering excellent editorial suggestions.