For four months I’ve been falling asleep most nights thinking about slabs of cold gray granite called Freeblast, the Boulder Problem, and Enduro Corner. I’ve consumed dozens of YouTube clips and interviews with rock climber Alex Honnold and filmmakers Jimmy Chin and E. Chai Vasarhelyi, who directed Free Solo, the extraordinary Performance story that recently won an Oscar, a BAFTA, and a backpack full of other awards. The Big Event in this Performance story is Alex’s ascent of Yosemite National Park’s El Capitan, a 3,000-foot granite wall, with no ropes or other safety devices. It’s a feat that has been described as akin to someone suddenly deciding to run a marathon in under an hour—something no other runner in the world would ever consider because it’s clearly beyond the boundaries of the human mind and body—and succeeding.

The difference between nonfiction and fiction is that in nonfiction, you actually do not know what’s going to happen next.

–E. Chai Vasarhelyi, Making the Impossible Possible

I’m not a climber and just barely a weekend hiker, but I’ve always been fascinated by stories of human courage and endurance, especially in the face of immense natural obstacles. Give me a brutal polar trek or a misguided Amazon adventure, and I’m all in, so that’s surely what drew me to the story at first. But Free Solo wouldn’t have held my interest for so long and led me to dive deeper into its structure if it were only about a superhuman athletic feat. The film is so much more than that and has a lot to teach us as storytellers.

If you’re interested only in how Alex’s approach to climbing—in effect, his approach to managing fear and “making the impossible possible,” as director Chai Vasarhelyi puts it—applies to writing, then skip to the bottom of this post, where I’ve tried to draw some lessons from the film. If you’re interested in dissecting the two narratives in the film—a Performance story and a Worldview Education story, then let’s rope up and do this in traditional Story Grid fashion, with some of our Six Core Questions:

What’s the Genre?

First some quick background: Free Solo is a story in which the collaboration of the two filmmakers is at the same world-class level as Alex’s climbing skills. Jimmy Chin started the project with decades of experience as a climber and photographer, the skills to assemble a team of equally talented climber-photographers who could pull off the shoot, and a long friendship with Alex, the subject of the film. Chai Vasarhelyi is an award-winning documentarian who specializes in intimate stories about people and knows how to capture human relationships in a natural, vérité style. Jimmy and Chai are also husband and wife, adding an extra layer to the collaboration.

I went into Free Solo having seen the couple’s previous epic mountaineering film, Meru. From that dramatic Action Adventure story I learned that climbing is less about conquest and more about mentorship and friendship—much like War genre stories. This theme of mentorship and friendships built on shared experiences is the lynchpin that holds together the Performance and Worldview stories in Free Solo.

I won’t have room to discuss every aspect, so check out Rachelle Ramirez’s comprehensive guides to the Performance genre here and of the Worldview genre here. And some of the best insights into how the Worldview Education genre works are found in the Story Grid Editors’ Roundtable discussion of the film The Fundamentals of Caring here. I have to give a shout out especially to Kim Kessler’s thoughts on exactly how the story is told because she really informed my thinking on Free Solo. Thanks, Kim!

The External and Global Genre: Performance

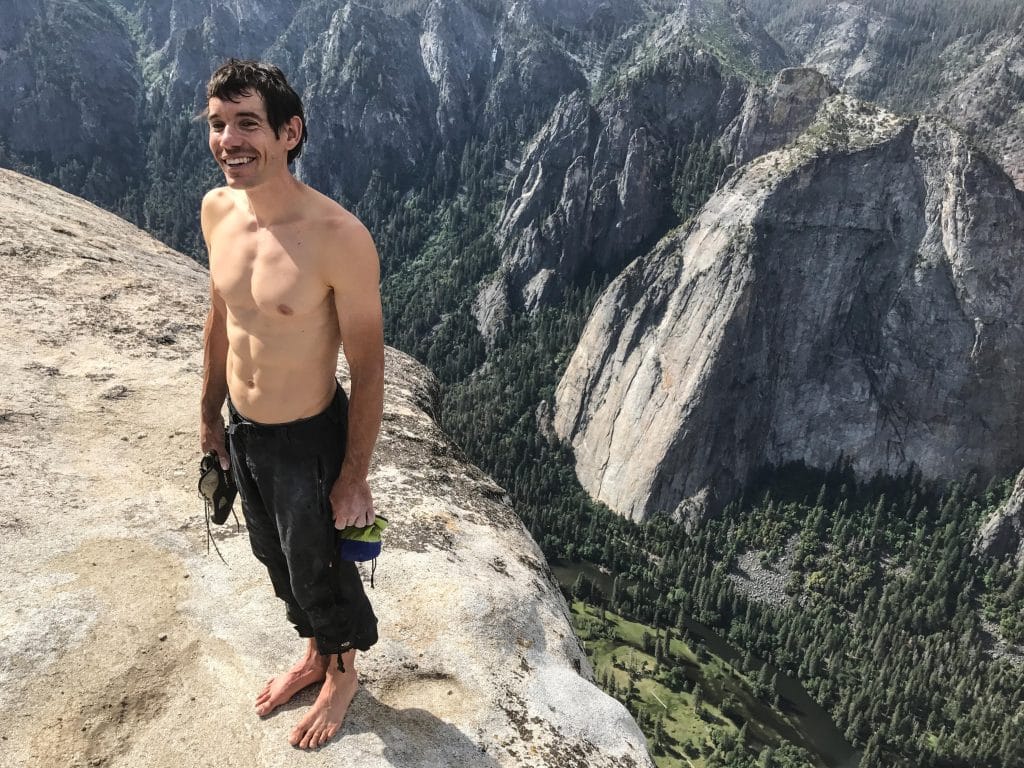

Free Solo begins and ends with Alex climbing without ropes in Yosemite. In the first scenes he’s ascending a wall that his mentor, Peter Croft, first climbed. Alex seems superhuman as he climbs, perfect in his mastery—but the camera keeps pulling back to show that he’s dwarfed by the landscape, and is actually tiny and vulnerable compared to the ancient, unforgiving rock he’s hanging onto. This fulfills one of the key conventions of Performance—that there be a wide and deep power difference between the protagonist and antagonist: It’s 5-foot, 11-inch Alex Honnold versus 3,000-foot El Cap. Check.

We know for sure this is a Performance story because all the signs point to a Big Event—Alex’s climb—as the Ending Payoff. What unfolds during the Middle Build, as he trains for the climb, are the three layers of conflict—an inner, personal battle against fear for Alex, interpersonal challenges with his friends and his girlfriend Sanni; and a larger, simpler external Human versus Nature conflict.

What About the Internal Genre?

I’ve settled on Worldview-Education as the Internal Genre, which turns on the values of meaning and meaninglessness. Alex’s internal journey in the film is toward deeper forms of connection with both his friends and his new partner, Sanni, than he has ever experienced before, which bring new meaning to his life. With a very light touch, the film reveals a few details about Alex’s lonely and disconnected childhood, the death of his father, his struggles throughout his twenties to overcome anxiety, and his methodical efforts to teach himself to talk to and touch other people. So for me, the subtext of the film is Alex’s search for deeper meaning and connection in his life.

Digging into Some Obligatory Scenes and Conventions

The pairing of the Performance and Worldview Education genres in Free Solo works so beautifully because many of the conventions and obligatory scenes are similar and complement each other as the two stories move forward together. Alex’s exterior climbing life and his interior emotional life criss-cross and shed light on how he deepens his own understanding of love and friendship.

Alex has two climbing mentors in the Performance story, Tommy Caldwell and Peter Croft. Both men are his heroes since childhood. Early on, Alex is more comfortable showing his affection for Tommy and Peter than for his girlfriend, Sanni. Both Caldwell and Croft express doubts about the El Cap climb for different reasons. Tommy fears for his friend’s life, and Peter questions the “purity” of the pursuit, wondering if Alex is doing it for the cameras instead of for himself.

How you make an ascent—the purity of your intentions and of your technique—is as important as reaching the top for world-class climbers. In a Performance story, a conflict with the mentor is usually one of the major complications, and a big question is whether the mentor will end up supporting or betraying the hero. Tommy pushes back gently on Alex’s free solo dream, but ultimately helps him train and offers love and support, explaining that if he didn’t help his friend prepare as well as possible, he couldn’t live with himself. Peter remains skeptical. He doesn’t openly oppose Alex’s plan, but he doesn’t help him, which in this life-or-death situation adds a psychological hurdle for Alex that—at least from my storytelling point of view—seems like a quiet form of betrayal.

In the Worldview Education story on the other hand, Alex’s girlfriend Sanni plays the role of mentor, gradually helping Alex see what a life based on close human relationships, love, and “being happy and cozy” might look like. She doesn’t betray or fail him emotionally, but her inexperience as a climber contributes to a whole series of events that threaten to derail Alex’s dream. She accidentally lets a rope go and causes him to fall during an easy climb, and is with him again for another, more serious fall when he sprains his ankle. The sprain helps to end Alex’s initial plan to climb El Cap in 2016. The question of whether Alex can achieve his dream and also have a meaningful, loving relationship is the heart of the Worldview story.

Tommy, who is married with two children, also acts as a mentor and model in the internal Worldview story. In a memorable Halloween pumpkin-carving scene, Alex greets Tommy’s toddler son cheerfully and awkwardly holds his daughter, threatening to drop her and joking about the fear and anxiety he’s feeling. The film cuts immediately to interviews with Alex and his mother that bring viewers into his childhood. His parents were estranged and eventually divorced and no one hugged or said “I love you” in the Honnold home. The sequence ends with a short voiceover by Alex that explains the controlling idea of the Worldview and Performance stories:

My mom’s favorite saying is Presque ne compte pas, “Almost doesn’t count.” Or, “Good enough isn’t.” No matter how well I ever do at anything, it’s not that good. The bottomless pit of self loathing. I mean that’s definitely the motivation for some soloing.

This is the only real moment when Alex tries to analyze his “why” in terms of the emotions involved in climbing, and for me, it’s the point where the connection between the external and internal stories is most powerful. Here is where we find out that his own self-loathing and “good enough isn’t” attitude is basically the antagonist in the internal story.

It would be easy for the film to blame Alex’s parents, especially his mother, here, but that’s not in keeping with Chai Vasarhelyi’s claim that this is a feminist film as well as a climbing film. We can never know everything that went into making Alex who he is. But certainly, part of what makes the film work is that Alex is climbing up from a “bottomless pit” that we all experience at some point in our lives. Audiences have responded so strongly because everyone has some sort of impossible wall to climb. We all want to escape some aspects of our childhoods and to not repeat our parents’ mistakes. And we’re all searching for perfection that seems forever out of reach. It’s a universal story in the guise of a one-of-a-kind superhero story.

From this point on, several of the key conventions of both stories suddenly become clear:

In the Worldview Story, the subtext is usually a big social problem, like racism, misogyny, or class conflict. I think in this story, the social problem is a classic American dilemma, and one that usually appears in Westerns: the conflict between individualism and community. It might actually be interesting to try to analyze Free Solo as a Western, but that’s a task for another day . . .

What I’m thinking at this point is that the “dirtbag” life that many climbers pursue—which is all about chasing individual goals, living alone in a van or tent, and having few strong attachments beyond the friends you run into on the side of each mountain—lost its meaning for Alex at some point, or he recognized it as meaninglessness disguised as meaning, in Story Grid terms.

In his mid-twenties, Alex began gradually to find ways of making community and human connections a bigger part of his life. He started a foundation based on improving some of the places he’d visited, making people’s lives better and acting as an environmental steward. Then just as he was starting to prepare for the most important climb of his life, and after some failed and superficial relationships, Sanni showed up to add one big progressive complication.

Like any great Performance story, much of the movie is made up of training sequences, with the longest and most intense coming just before the climb. We watch Alex’s skills being honed and begin to understand how he battles fear through meticulous preparation. His All is Lost Moment on El Cap is an aborted attempt to free solo in 2016. He goes to his mentor Peter and admits he just couldn’t make the climb as he intended. It didn’t feel right. This is also an “all is lost” moment with Sanni as he explains that—despite the fact that they’re going through the motions of buying a house together—his goals and hers just don’t mesh, and it’s hard to imagine at that point in the film how they will stay together:

Alex: For Sanni, the point of life is like, happiness. To be with people that make you feel fulfilled and to have a good time. For me, it’s all about performance. The thing is— anybody can be happy and cozy. Nothing good happens in the world by being happy and cozy. You know, nobody achieves anything great because they’re happy and cozy.

Sanni: You never want to feel like you’re getting in the way of someone’s goal. And it’s really hard for me to grasp why he wants this. But it’s his dream and he obviously still really wants it.

These realizations come near the end of the Middle Build, just before Alex’s final intensive training and ascent of El Cap.

What’s the Point of View?

Like many documentaries, Free Solo uses multiple points of view. The filmmakers allow Alex, Sanni, and Tommy to speak for significant stretches of the film, with Jimmy (the director), Mikey (a cameraman, climber, and one of Alex’s oldest friends), Peter, and Alex’s mother Deirdre, offering their perspectives too.

The voice you hear most is Alex’s, but by no means is it just a first-person film. I think the way that Jimmy and Chai weave the voices together to create multiple points of view is one of the reasons it’s so effective and moving. But in the end, the strongest point of view is the directors’, of course.

What are the Protagonist’s Objects of Desire?

In both the Performance and the Worldview Education stories, Alex is clearly the protagonist, but his objects of desire (both wants and needs) differ in each story.

Performance: Wants and Needs

There’s no question that climbing El Cap is the Big Event and Alex’s “want” in the Performance story. His need is to feel perfect in order to escape the depression and melancholy that

After the filmmakers show us a tearful Tommy saying that he’s stressed out over Alex’s imminent climb, they cut to Alex, explaining his own feelings:

Look, I don’t wanna fall of and die either, but there’s a satisfaction to challenging yourself and doing something well. That feeling is heightened when you’re for sure facing death. You can’t make a mistake. If you’re seeking perfection, free soloing is as close as you can get. And, uh, it does feel good to feel perfect for a brief moment.

Worldview Education: Wants and Needs

In the Education story, Alex wants to find a way to have a serious relationship with Sanni—he keeps demonstrating that he doesn’t want to give her up—while also still pursuing his climb of El Cap. Both these things bring meaning to his life. What he needs, I think, is to understand and experience the emotions that go with this relationship, and all his relationships. Just after Tommy’s tearful admission and Alex’s explanation of “seeking perfection,” the filmmakers cut to a jarring moment of Alex dismissing all his friends’ concerns about him falling to his death, including the fears that Jimmy and the rest of the camera team have already talked about repeatedly:

My friends are like, “Oh, that’d be terrible,” but if I kill myself in an accident, they’ll be like, “Oh, that was too bad,” but life goes on, you know. Like, they’ll be fine. And I mean I’ve had this problem with girls a lot, you know. They’re like, “Oh, I really care about you.” And I’m like, “No, you don’t.” If I perish, it doesn’t matter. You’ll find somebody else. Like, that’s not that big a deal. I don’t know . . . maybe that’s a little too callous.

When in the Ending Payoff, Alex is ready to begin his actual climb, the fact that this is not about one superhuman climber going it alone is clear. There has been a change in his mindset. He tells the camera team—all of whom are his friends—to use remote cameras at the most difficult pitch, the Boulder Problem. He fully understands now that it’s

By the time the breathtaking climb is over, Alex celebrates with Jimmy, as Jimmy cries, and Mikey—a friend and cameraman who was too nervous to watch most of the climb—finally smiles.

At one point in the film Tommy has told us that Alex just doesn’t cry, and at another point Sanni has explained that he doesn’t say “I love you.” In the final few minutes of the film, Alex calls Sanni joyfully—”just delighted” that he’s achieved the impossible and says that he loves her. He also says that he feels like crying, but insists on keeping it together in front of the cameras. He then calls Tommy to thank him for all his help. In the audience, we sense that Alex has turned a corner of some kind in terms of feeling his own emotions and being able to express them.

What’s the Controlling Idea or Theme?

Performance

The primary value shift in a Performance story is between shame and respect. So expressed simply, the controlling idea of a performance story with a positive ending like Free Solo’s is usually something like: We gain respect when we commit to expressing our gifts unconditionally.

Alex gained self-respect and the respect of his peers and the world because he remained committed to his goal and did it his way. He ignored the voices that questioned him—even the voices of his mentors— and stopped during one attempt because it didn’t feel right. He hadn’t put in the time he needed. He did the work he needed to do in order to step outside the fear.

The big challenge is controlling your mind, I guess. Because you’re not controlling your fear, you’re trying to step outside it.

Theme: Alex gains self-respect and the respect of the world by training methodically and relentlessly in order to step outside his fear and free solo El Cap.

Worldview Education

The primary value shift in a Worldview Education story is between meaninglessness and meaning. So expressed simply again, the controlling idea of a Worldview Education story is something like: Meaning prevails when we express our gifts in a world that we accept with all its imperfections.

One of Alex’s greatest gifts is his ability to teach himself to become a better person by observing others and creating detailed plans to attack his own shortcomings. Viewers understand this process because they’ve heard about the methodical way he taught himself to eat vegetables and hug other people. It’s a painful process, but throughout the film, we see Alex observing Sanni, Tommy, and the rest of his friends, and gradually coming to some understanding—even if still imperfect—of their feelings. By the end we doubt that he’ll ever repeat the idea that his death just wouldn’t matter to anyone.

Theme: Alex finds meaning in his relationships by using his talent for observation and methodical self-improvement to become more connected and to express his emotions.

At the risk of sounding too touchy-feely myself, I think the real triumph at the end is that Alex steps outside his fear of love.

Free Solo’s Lessons for Writers

Show your protagonist’s flaws. Alex is a sympathetic hero because we see so many of his weaknesses, including some unkind and dismissive moments with Sanni, that are painful to watch. He’s not just a pure, noble “warrior” as he likes to think of himself, and this makes both the Performance and Worldview Education stories so much stronger.

Trust readers to understand what’s happening without over-explaining. It’s a film, of course, so there’s a heck of a lot more showing than telling in this story. The directors trust us to gradually figure out what some of the climbing jargon means and to learn with Alex which areas of the wall to watch out for. There’s minimal description and the movie is better for it. Action and characters take precedence, so that it’s not a how-to manual, but a compelling story.

Practice is the only way to “turn pro” as Steven Pressfield would say. You’ve got to practice constantly in order to memorize the holds, to know which foot should go where, and when to move and twist in a particular way. And practice is the only way to lose—or step outside of—our fears. The same thing is true for any kind of writing. Writing every day, up and down the cold white sheets of paper, doesn’t remove all our fears—writers are notoriously susceptible to imposter syndrome, fear of failure, and fear of success! But the familiarity of the work when we do it every day, the repetition and routine of it, help us step outside our fears and keep going until we climb over the last crag and can celebrate with our friends.

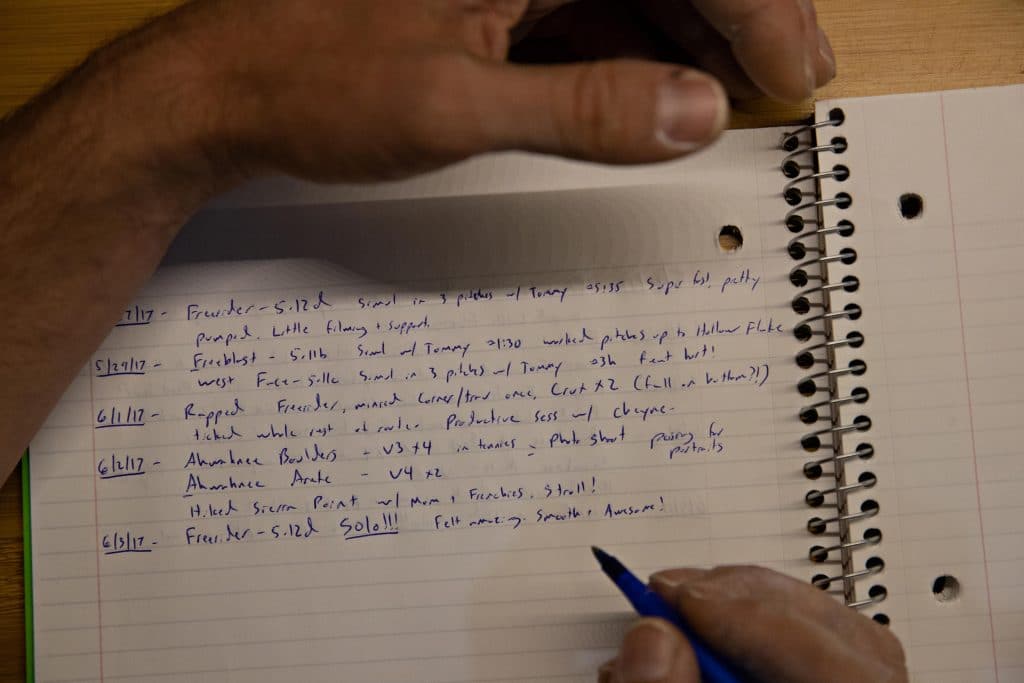

Climbing journals and craft journals. Take notes on your process so that you can refine it over months and years. Alex keeps detailed climbing notebooks in which he records how he has attacked specific climbs, what he did well, and what just didn’t work. It never occurred to me before to keep that kind of notebook, but it seems so logical and helpful now. Why not keep a record of each project, no matter how small, and a few notes about the successes and failures as we see them

Everyone needs a mentor. Or two.

Add a unicorn. It makes every story better. (If you haven’t seen Free Solo—Yes, there’s a unicorn in the movie.)

**Full Disclosure: Free Solo was released by National Geographic Documentary Films. Ten years ago I was on staff at National Geographic magazine. I’ve never had an affiliation with Nat Geo Films.