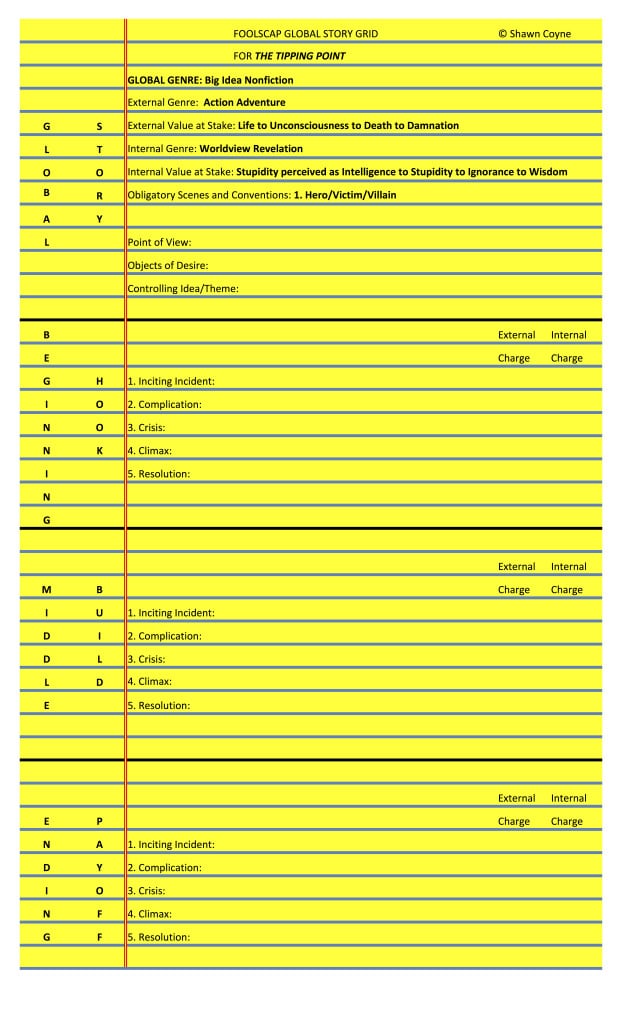

Here is our progress so far on our Foolscap Global Story Grid for The Tipping Point.

Seeing the way Picasso boiled line drawing a bull into its most essential strokes inspires artists.

Seeing the way Malcolm Gladwell somehow delivers a “hero at the mercy of the villain scene” in his external genre Action Adventure component in The Tipping Point will be equally thrilling.

Let’s review the OS and Cs that Gladwell faced for his Big Idea Nonfiction project.

1. Hero/Victim/Villain

The first one we’ve listed is the crucial convention of the Action Adventure story, the necessity of having a cast that includes at least one hero, at least one victim, and at least one villain. We’re clear that we have that convention covered. Here’s the post that explored that necessity.

2. Destination/Promise

What we also need in an Action Adventure Story is a clear Destination. What I mean by that is we need to be given a quest at the very start of the story that has a clear purpose. I always use L. Frank Baum’s The Wonderful Wizard of Oz as the epitome of the Action Adventure Story and its destination is, of course, The Emerald City, the center of Oz where the Wizard resides.

In the case of the Big Idea Nonfiction Story, the destination is not just understanding the Big Idea itself, but applying that understanding to get a clearer view of the world. The Destination/Promise is applicable knowledge.

3. Path/Methodology

The third thing we need in an Action Adventure Story is a clear path to the destination, a yellow brick road. By following the path we will reach the promised land.

In the case of Big Idea Nonfiction, the path is inherent in the methodology of the investigator/narrator. And that methodology is the logical progression of the storyteller’s adherence to the universally accepted form of discovery—the Scientific method.

I’ll do a post on the Scientific Method down the road.

4. Sidekick/s

The sidekick/s in an Action Adventure Story are the equivalent of the scarecrow, the tin man, and the lion in The Wonderful Wizard of Oz. These characters exemplify a component of the global hypothesis. For example, in The Tipping Point Gladwell introduces the reader to everyday people like Roger Horchow, Lois Weisberg, and Mark Alpert to represent building blocks of his theory.

5. Set Pieces/Weigh Stations

The Action Adventure Set Pieces are mini-stories within the global story. Essentially these are sequences with a central dilemma that must be solved before the global story can move forward. If Dorothy does not throw water on the Wicked Witch of the West after she’s been abducted by the witch’s winged monkeys, we’d never learn the truth about the Wizard of Oz.

Similarly in a Big Idea work of Nonfiction, if we are not convinced by Malcolm Gladwell’s assertion that products/ideas tip in much the same way as viruses overwhelm a host, we’d never understand the importance of “stickiness.”

It’s important to remember that the storyteller needs to escalate the stakes of each of the Set Pieces/Weigh Stations as the global journey/story progresses. Just as L. Frank Baum had to figure out exactly where in the hierarchy of danger the winged monkeys fell, so does Gladwell have to prioritize the set pieces/weigh stations of his global story. Gladwell doesn’t begin The Tipping Point with the set piece/weigh station about suicides in Micronesia. He builds to them with lighter fare about Hush Puppies and less specific examples about overall crime rates in New York. It’s not the evidence presented in a Big Idea Book that makes it compelling, it’s the order in which the writer chooses to deliver the evidence…

6. Hero at the Mercy of the Villain Scene

The “hero at the mercy of the villain” scene is the core event of every action story including Action Adventure. The Wonderful Wizard of Oz moment is when the Wicked Witch of the West has Dorothy on the ropes. She’s gonna get our heroine’s shoes and then all will be lost. That’s when Dorothy melts the witch with the water.

Malcolm Gladwell clearly states that he’s written an Intellectual Adventure Story so we need to figure out exactly where and when he gives us the “hero at the mercy of the villain” scene. I have some ideas about that but I need to take my time and really parse it out in the Story Grid Spreadsheet of The Tipping Point before I’ll share them.

Those are my big six OS and Cs for Action Adventure. So I’m going to note them on my Foolscap for The Tipping Point.

I’m also going to add three more must-haves to cover the necessities for the Internal Genre, Worldview Revelation, in the Big Idea Nonfiction book. They are:

7. A Blatant Statement of the Controlling Idea

Unlike fiction’s controlling idea/theme which is delivered in subtext, for Big Idea Nonfiction, the controlling idea must clearly be stated. In as few words as possible. As soon as possible. The statement of the big idea is the inciting incident of the entire Big Idea Book. It’s the must-have throwdown raison d’etre of the book–after years of diligent hard work, here is what I’ve discovered. Now follow me and I’ll walk you through exactly how I pieced this life changing information together and then I’ll tell you how to apply this information in your own life.

8. Ethos/Logos/Pathos

As I wrote about here, the Big Idea Nonfiction book must use all three forms of argument to build/prove its case.

9. Ironic Payoff

Lastly, the Big Idea Nonfiction book must “turn.” What I mean by that is that while the promise of the book (proving the idea and then giving the readers the necessary tools to apply the idea) must be paid off, it also must do so with a surprising twist.

The pursuit of the idea and applying it potently reveals a deeper truth, one that the storyteller delivers to the reader at the ending payoff.

In The Wonderful Wizard of Oz, the irony is that the Wizard is impotent. It is the power within each of the characters who seek his approval/permission that truly grants them their wishes. Not the Wizard’s magic.

So it is in The Tipping Point… To tip a product or a behavior is not all it’s cracked up to be. In the end, the book reveals that scale requires compromising sacrifice and that it also has a very dark side. So while empowering, to know how to tip something is also potentially catastrophic. There is as much darkness inherent in The Tipping Point as there is light. It is a viral phenomenon in every sense of that word.

For new subscribers and OCD Story nerds like myself, all of the Storygridding The Tipping Point posts and The Story Grid posts are now in order on the right hand side column of the home page beneath the subscription shout-outs.