Joseph Campbell popularized the Hero’s Journey that has become a mainstay among writers. But he also said the symbols of ancient myths no longer fit the modern world. This is why we need to add the heroine’s journey to our myths.

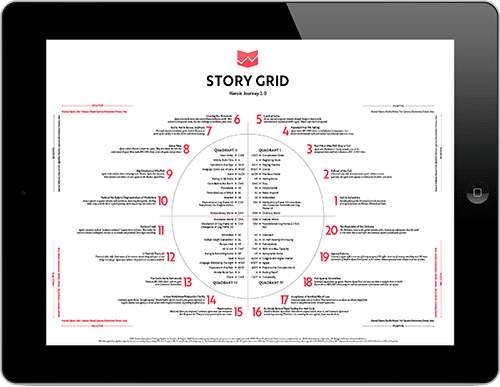

Are you writing a Heroine's Journey?

Download our highly detailed infographic outlining the 20 major scenes you must have in every story.

We Need New Myths

Myths are archetypal stories that reflect our inner selves. They reveal our foibles and laud our innate strengths so that we can better understand our shared humanity.

But society has changed a lot since Theseus slew the minotaur.

“When the world changes, then the religion has to be transformed. The only mythology that is valid today is the mythology of the planet—and we don’t have such a mythology.” – Joseph Campbell

Campbell was right about our changing world. We face challenges our ancestors never even dreamed of.

- Technology revolutionizes our lives. We’ve transferred much of our making and thinking to computers. We socialize online. Memory is digitized.

- Societies struggle to cope with conflict and suffering based on socioeconomic, racial, and gender inequality.

- In business and politics, women are still subject to lower wages and discriminatory policies.

- The Earth itself is in critical danger as climate change impacts land, sea, and air, and alters the habitats of plants and animals.

In a recent tweet, Glasgow International Fantasy Conversations affirmed:

“The great theme of our age is one of loss. In a time of ecological crisis, we need stories. We need to imagine better tomorrows, stories as alibis that get us through the day.”

This failure of old myths to deliver answers is echoed in the very movie franchise that put the Hero’s Journey into popular culture.

In The Force Awakens, Rey exclaims, “Luke Skywalker! I thought he was a myth!”

She speaks for all of us in The Last Jedi when she implores Luke, “I need someone to show me my place in all of this.”

Luke reveals his disillusionment. “I only know one truth: It’s time for the Jedi to end.”

The loss of meaning in one’s life is painful to him—and to us, the audience—a feeling that echoes all too well our era of crisis and loss.

But when a myth becomes part of the collective memory, it’s remarkably persistent. We see that in the repetition of stories and movies based on the Hero’s Journey. The only way to change an outdated myth is to replace it with a better one, whose symbols make more sense and resonate with contemporary society. In this post, I’d like to look at alternative stories of self-discovery based on a pattern called the Heroine’s Journey.

A Female Perspective

Female action heroes like Wonder Woman’s Diana Prince and Divergent’s Tris rake in big bucks for Hollywood, showing that a woman can carry an action film and attract huge audiences. These movies stick to the basic shape of the Hero’s Journey, just replacing the male protagonist with a woman. That’s not necessarily a bad thing, but it’s the same old story dressed up in a new outfit.

In movies like Thelma and Louise, where women break the rules, the audience feels empowered. In this David and Goliath trope even when the heroines take freedom to the ultimate extreme, we feel that justice has been done in a fight against an unfair system.

In real life, women who push back against societal norms aren’t always seen in a positive light. “Nevertheless, she persisted,” originally meant to denigrate Senator Elizabeth Warren’s resistance to a male colleague’s effort to stop her from speaking, epitomizes how women who dare to challenge the patriarchy are seen. Intended to demonstrate, the catchphrase was transformed into a feminist call to action.

Psychologists, mythologists, and writers have searched for feminine alternatives to Campbell’s monomyth, one that gives women and disenfranchised protagonists the agency and power to carry stories that follow a different path to self-actualization. From this search, the Heroine’s Journey was born. But unlike the classic Hero’s Journey, there are multiple versions of a Heroine’s Journey. Let’s take a look at two of the best known.

Maureen Murdock’s The Heroine’s Journey

Maureen Murdock wrote The Heroine’s Journey as counterpoint to Joseph Campbell’s Hero with a Thousand Faces.

When she asked Campbell about women and the Hero’s Journey, he famously responded:

“Women don’t need to make the journey. In the whole mythological tradition, the woman is [already] there. All she has to do is to realize that she’s the place that people are trying to get to.”

This reply inspired Murdock, a trained psychologist, to dig deeply into the realms of myth and psychoanalysis to develop an archetypal pattern of a woman’s quest for enlightenment and wholeness: the Heroine’s Journey.

You can trace the path of Heroine’s Journey in two popular stories. In the Pixar movie Brave, the protagonist Merida closely follows Murdock’s model as she struggles to make a place for herself without compromise in a fantasy version of medieval Scotland. And, notably, Zuko from the animated series Avatar the Last Airbenderalso follows a path that mirrors the Heroine’s Journey, which contributes to a powerful redemption arc of emotional depth and sensitivity.

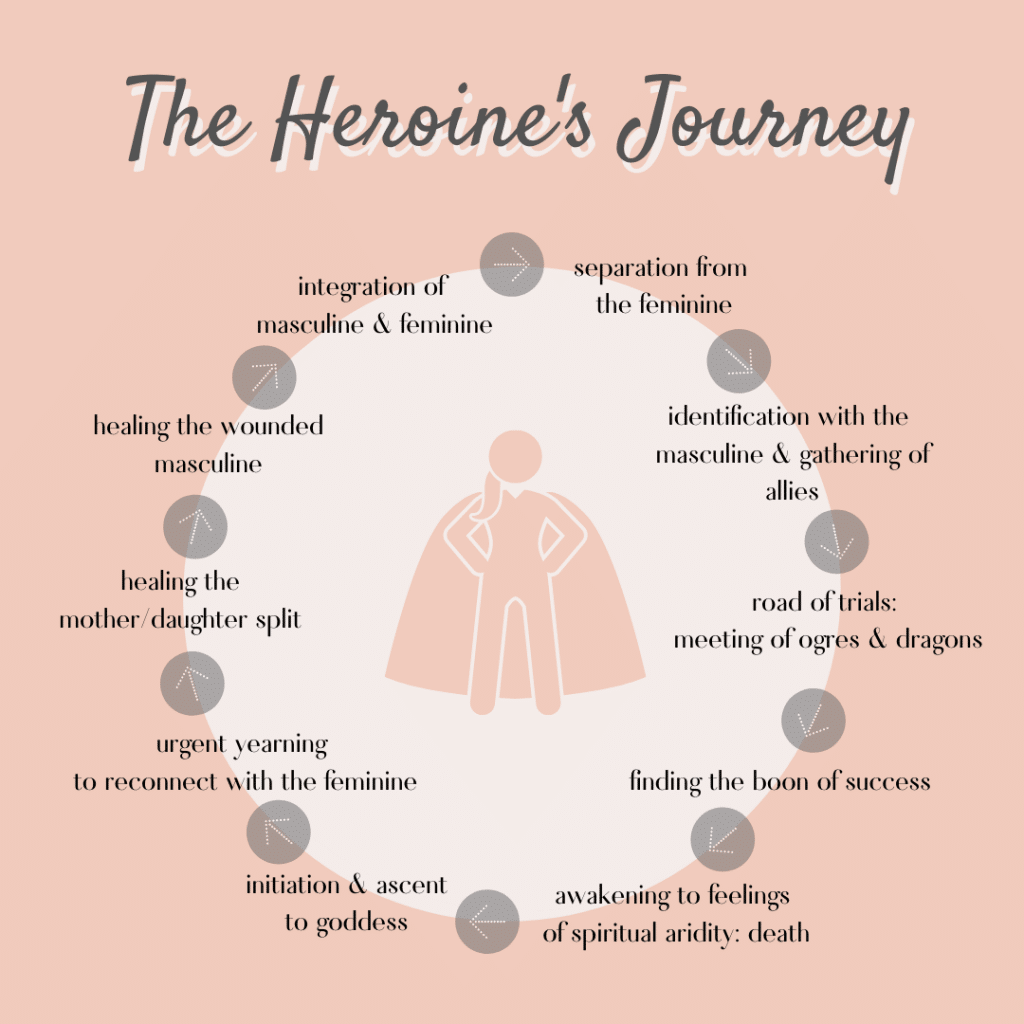

The journey includes ten stages, modeled here:

The Heroine’s Journey

1. Separation from the Feminine

Women leave the nurturing shelter of the archetypal Mother behind. Some strike out in search of success and and a sense of self. Others flee from the negative associations of feminine behavior, wanting to be taken seriously and not unrealistically sexualized.

2. Identification with the Masculine

To flourish in a male-oriented world, successful women often emulate male behavior by abandoning the domestic sphere, suppressing emotional displays, and adopting male traits in the boardroom or on the campaign trail. Merida rejects traditional women’s activities such as needlework. She excels in archery, defeating all her potential suitors in a competition. Zuko is separated from the nurturing love of his mother as a child and thrust into his father’s world of domination through conquest.

3. The Road of Trials

The heroine confronts challenges and obstacles to her goals. She survives trials, earns degrees, or learns difficult skills. She must balance her personal and professional lives. She must prove herself to those who think she’s not worthy to succeed by male standards. Zuko chases the Avatar to restore his honor.

4. The Illusory Boon of Success

Having overcome her trials, the heroine attains a measure of success, a powerful title, position, or wealth. She is a superwoman who has it all. Imposter syndrome still sneaks in, and she wonders when she will feel she has truly succeeded.

5. Awakening to Spiritual Emptiness

Despite her successes, the heroine feels empty. She senses that there must be more to life. She may feel betrayed by the system or by her allies. She hears her inner voice after years of ignoring it. Even when he has returned home and regained his honor, Zuko finds the victory hollow. He questions his feelings and realizes that he has chosen the wrong path.

6. Initiation and Descent to the Goddess

The heroine experiences the dark night of her soul. She sometimes withdraws from friends and family. She no longer sees the point in struggling for success by her previous terms. The heroine must face her Shadow, an archetype that, simply put, represents the things within herself that hold her back from what she truly needs. She learns to be, not to do. Merida travels deep into a wild forest to seek help from an old wise woman or witch. The Wise Woman is a strong archetype in her own right, the dark face of the Goddess representing danger and wisdom.

7. Yearning to Reconnect with the Feminine

Having rejected the pursuit of outward success, the heroine may end associations with people or institutions that compromise her newly awakened spiritual growth. She turns to creative work and activities that enable mind-spirit-body connections. She begins to purify herself for the next stage.

8. Healing the Mother/Daughter Split

The heroine reconnects with her roots and finds strength in the past. She emerges from the darkness with a deeper sense of self. She is able to nurture others and be nurtured by them. She reclaims feminine traits she once saw as weak. Merida must draw upon her knowledge of the feminine activities she rejected in order to save her mother from an enchantment.

9. Healing the Wounded Masculine

Having reoriented her concept of femininity, the heroine must shed toxic perceptions of masculinity. If she has rejected her earlier pursuits in the male-oriented world, she searches for what remains meaningful to her. She casts aside unrealistic concepts of men. Having rejected his father’s (and nation’s) violent traditions, Zuko’s loses his firebending skills until he learns how to use them in positive rather than destructive ways.

10. Integration of Masculine and Feminine

Our heroine has come full circle. Male and female aspects of personality are integrated in a union of ego and self. She is whole and capable of genuine love for others. She remembers her true nature. Not until Zuko joins up with Avatar Aang, who represents the antithesis of violence, is Zuko able to integrate his dual nature and achieve wholeness on his own terms before bringing balance to the world. Merida, too, has learned to embrace the different aspects her life. She accepts the value of her mother’s instruction in feminine pursuits while retaining her interest in archery and other stereotypical masculine activities.

Murdock’s model has roots in the women’s movement of the Sixties and Seventies, with a generation who raised their fists against the status quo. She and her contemporaries had heavy cultural shackles to break. Their efforts enabled subsequent generations to build on and benefit from a growing acceptance of the equality of women.

The Heroine’s Journey described by Maureen Murdock is a quest for integration and healing. The circle closes with the union of male and female, representing a journey toward spiritual and societal growth.

Its real strength is found in its understanding of the duality of human nature. The yin-yang symbol incorporates dark in the light, and light in the dark. There is strength in our Shadow selves, but only when we face our personal demons does our Shadow step aside and let us move forward.

Murdock built her model as a path for introspection and self-awareness, not specifically as a tool for writers. Nevertheless, it is one of the most widely known versions of a female counterpart to the Hero’s Journey.

Kim Hudson’s The Virgin’s Promise

Author Kim Hudson describes the Heroine’s and Hero’s Journeys as “two halves of a whole.” Although The Virgin’s Promiseportrays a feminine take on the search for one’s authentic self, it avoids limiting the gender of the protagonist. Viola in Shakespeare in Loveexemplifies the journey with a female lead and Billy in the movie Billy Elliot, is a male protagonist following a similar path.

Hudson developed her model for writers, specifically screenwriters, so it’s structured in three acts and frames archetypes and imagery in storyteller’s terms.

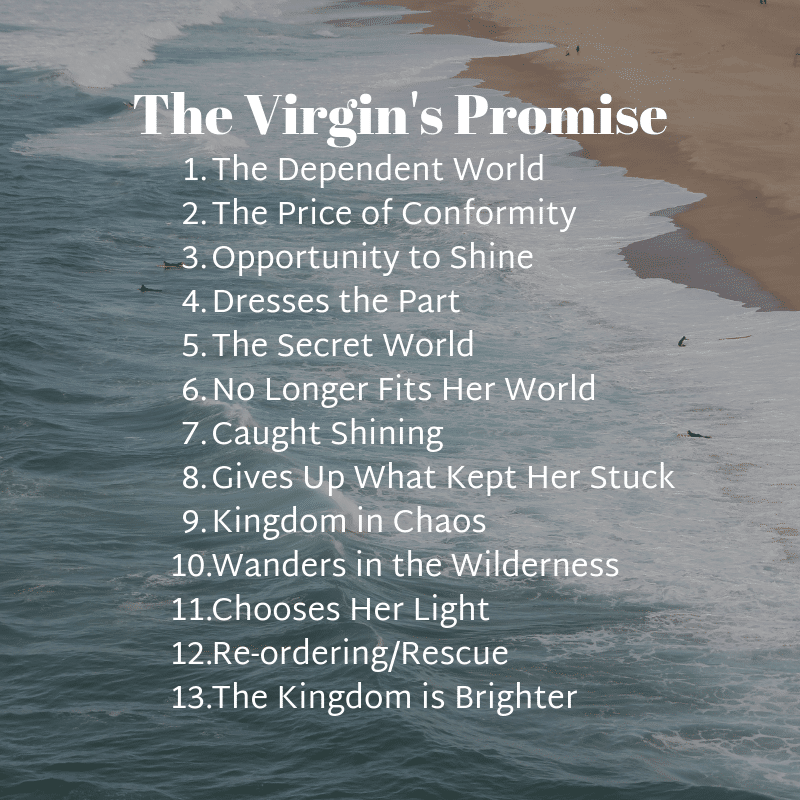

Some of the thirteen stages in this model have no equivalent in the Hero’s Journey. They reflect, instead, an inner emotional approach to life’s challenges. The thirteen stages are:

1. The Dependent World

The protagonist is tied to her normal world in order to survive, either by social convention, physical protection, or as a stipulation of conditional love. She is dependent on others to get by.

2. The Price of Conformity

The Virgin suppresses her inner gift to maintain the status quo. She may not realize she is captive in her Dependent World, or she may be critically aware of the need to hide her true nature. She may believe the low opinions others have of her and feel worthless. She is unable to break her chains or spread her wings.

3. Opportunity to Shine

A chance to express herself comes without risk to her dependent world. She may discover a talent, be pushed to it (fairy godmothers are great at this), or she may act in the interest of another person who requires her help. She recognizes a dormant part of her soul, or uses her talent in a new way.

4. Dresses the Part

The Virgin realizes her dreams may actually be within in reach. “Dressing the part” means she willingly steps into a role. In Shakespeare in Love, for example, Viola dons costume and becomes an actor. Cinderella wears a magical gown and goes to the ball after all. Sometimes, the Virgin receives an object or talisman that symbolizes her secret self. She “becomes beautiful” physically, metaphorically, or both.

5. The Secret World

Now she has a foot in the world of her dreams yet remains unwilling (or unable) to leave her old life behind. People might depend on her. She may be in physical danger, or fears the consequence of letting go of the Dependent World. Change is a hard thing. Who hasn’t hesitated before plunging into the unknown?

6. No Longer Fits Her World

As the Virgin discovers her true nature, she realizes her double life can’t go on. The risk of being caught increases. She may feel that she’s still an outsider in her secret world. Her behavior ranges from risk-taking to rejecting her dreams, thinking she can return to the way she used to be.

7. Caught Shining

The Virgin is revealed, exposed in one world or the other by betrayal or changing circumstance. Her secret is secret no longer. She may reveal her newfound strength by coming to the rescue of another. Ayla, in Clan of the Cave Bear, exposes her skill with a forbidden weapon by saving a child from a hyena.

8. Gives Up What Kept Her Stuck

Many things may hold the Virgin back: fear of losing loved ones, being hurt by a new love, fear of success or loss. Now she faces those fears and breaks the hold that others have on her. Sometimes the Dependent World vanishes and she finds herself on her own for the first time. She is her own boss, the mistress of her fate.

9. Kingdom in Chaos

In the wake of her assertiveness comes disruption. She has rocked the boat and changed the status quo by her rejection of the things that held her back. She has upset the old order and the Dependent World may come after her with all its strength in order to re-establish itself.

10. Wanders in the Wilderness

The Virgin faces her moment of doubt. Despite her newfound confidence, things don’t go as planned. Her belief in herself is tested to the max. Things might look very good back home, tempting her to give up her crazy notions of independence.

11. Chooses Her Light

But the Virgin eventually chooses to shine. She expresses her gifts in an imperfect world, accepting her flaws and her strengths. She gains new insights about the world she left behind. Power has shifted, and she now holds at least some of it. She can take care of herself and has become a self-actualized soul. But her journey doesn’t stop here.

12. Re-ordering/Rescue

The world readjusts itself around her. The Virgin broke ties with the Dependent World in Stage 8. Now she returns to her community. Her transformation makes the old world a better place. She reunites with people she loves who recognize and value her true self. She is no longer controlled by others.

13. The Kingdom is Brighter

Not only has the Virgin grown, but the world has also become a better place as a result of her journey. She integrates her inner self with the outer world. Hudson explains, “She has moved from knowing conditional love to unconditional love.”

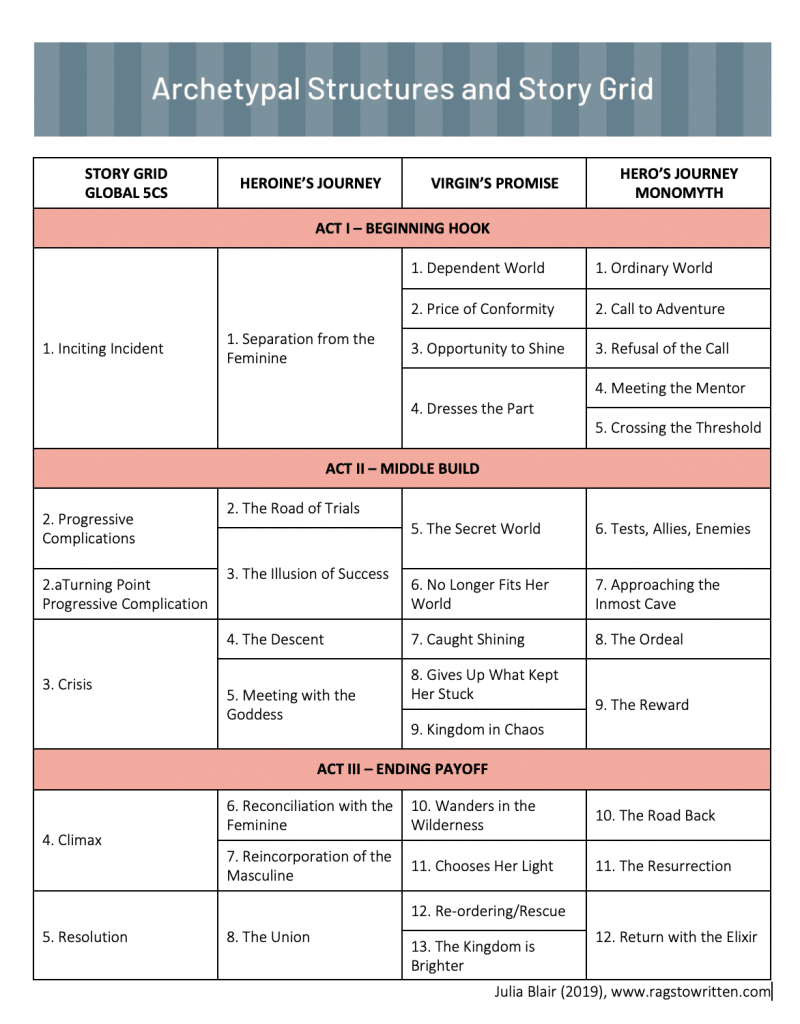

Shared Elements of Male and Female Archetypal Journeys

The Heroine’s Journey and The Virgin’s Promise show us what stories are like when women achieve their full potential. The Heroine’s Journey (HJ), The Virgin’s Promise (VP), and the monomyth (MM) share some elements, demonstrating that at least some components of heroic stories are universal:

- The protagonist rejects or suppresses part of themselves to fit in the normal world. HJ: Separation of the Feminine; VP: The Price of Conformity; MM: Call to Adventure, Rejecting the Call.

- The protagonist expresses new talent or knowledge without risking themselves. For a while, things look like they’ll work. HJ: The Illusion of Success; VP: The Secret World; MM: Tests, Allies, Enemies.

- The protagonist experiences a moment of doubt. They wonder if they have chosen the right path and if they can return to the way things used to be. HJ: The Descent; VP: Wanders in the Wilderness; MM: Approaching the Inmost Cave.

- Continuing on the journey, the protagonist does what they must to defeat their demons, conquer the adversary, or complete their quest. HJ: Reconciliation with the Feminine, Reincorporation of the Masculine; VP: Chooses Her Light; Wanders in the Wilderness; HJ: The Road Back, The Final Battle.

- The protagonist integrates their conflicting selves, rejoins the world, brings inner and outer balance. They have transformed themselves and the world. HJ: The Union; VP: Reordering/Rescue; MM: Return with the Elixir.

(The VP crisis occurs in Act III. In HJ and MM, the crisis takes place in Act II.)

You can download a printable version of this chart here.

Contrasts with the Hero’s Journey

The male and female journeys of self-actualization follow different paths but arrive at a similar destination. Both trace a voyage of self-discovery, of confronting and breaking down self-deception and learning to integrate aspects of personality in positive, productive ways.

Heroine’s journeys are about self-worth and identity. The heroine brings balance to herself, then changes the world around her. It’s more about the journey than the destination.

The Hero’s Journey is a quest for an external objective. It is about obligation and rising to the task. The Hero seeks to right a wrong and bring balance to the world. In doing so, he is transformed.

One of the loudest and most legitimate complaints to be made about the Hero’s Journey is that it’s become formulaic. The constant barrage of mediocre action/adventure sequels out of Hollywood attests to that. I’m not saying it’s time to abandon the Hero’s Journey. It’s still capable of surprises. Star Wars’Darth Vader arc gives us a failed Hero’s Journey and a fascinating character study. The Cohen brothers’ O Brother, Where Art Thoudelivers a twist on the classic with escaped convicts as heroes. As writers create new variations on a theme, the archetypal pattern is shifting.

Putting It To Work

If you read my post on archetypes, you know I believe that writers have the ability and responsibility to bring joy, hope and change to the world. Myths and archetypes are powerful tools for accomplishing that.

While reading about alternatives to the Hero’s Journey, I began to see that the Heroine’s Journey and Virgin’s Promise are more than just female versions of the monomyth. They meet the responsibility to spark change because they arose in response to a need for change.

Immutable Story Grid Truth: All good stories are about change.

All of them. Without exception. In every scene, sequence, and act there must be a change, or it’s not a working scene, sequence or act. Characters must change or fail.

The Virgin’s Promise and the Heroine’s Journey are different ways to achieve transformation. They’re alternative narrative structures that can breathe new life into the stories we tell and have the potential to bring some hope and joy as well.

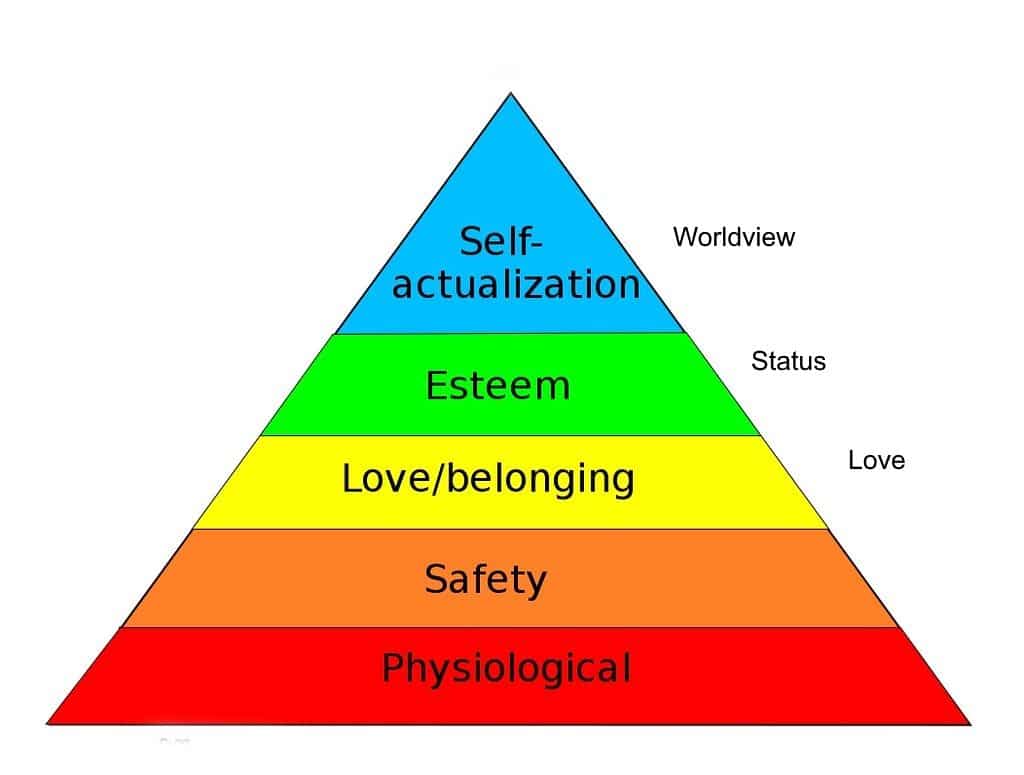

In Story Grid terms, these models relate to the higher ranges of Maslow’s hierarchy of needs. You’ll find them especially good fits for the internal genres of Worldview (self-actualization) and Status (self-esteem). You can also find elements of these models in the Love Story, an external genre, when characters seek a mature and unconditional love.

MASLOW’S HIERARCHY OF NEEDS

Balancing internal and external genres within a plot is one of the hallmarks of a compelling story. Both Heroine’s Journey models enable us as writers to delve into the psyche of a character in a different way. They inspire new responses to the challenges of change and growth and the consequences of failing to change.

How might your current work-in-progress benefit by incorporating elements of the Heroine’s Journey?

Consider how your protagonist changes through the course of your story. Are they thrust into a situation that forces them to change whether they want to or not? Very often that’s the monomyth, and you can draw from the stages of the Hero’s Journey for inspiration.

Does your protagonist feel a growing dissatisfaction with the way things are? Are they faced with the realization that the problem is something inside them? Are they held back by external circumstance and lacking opportunity for their inner gift to bloom? You’ve got a great candidate for the Virgin’s Promise or Heroine’s Journey.

A Call To Action

Old myths are no longer as relevant in our complex 21stcentury world as they once were, but we’ve not yet replaced them with something as strong and inspiring—and we need to. Campbell says that the most important purpose of myth is to guide humans through the stages of life, from cradle to grave.

Robert McKee, an authority on writing powerful stories, tells writers to write the truth. The truth is, we need desperately need new myths to guide us forward in a compassionate and enlightened way.

So where do new myths come from?

Mythologists don’t create our myths, they study them. They dissect them, examine the pieces, investigate symbols and themes. But myth is far more than just the search for meaning. It is the experience of meaning.

That’s precisely what happens inside a reader’s head when they read a book. Consuming stories gives readers the experience of meaning. Stories are how we deliver the new myths that the world needs now.

You, dear writer, are a mythmaker.

It’s our calling as writers to create new myths, to draw upon our experiences, uncover new symbols, and reinterpret archetypes.

McKee and others tell us that through story, people experiment with change without risking themselves. Readers and movie-goers try on different mindsets and personas, just like trying on clothes before a mirror.

When they find something that fits, a new way of thinking about themselves, the world, and themselves in the world, you the writer have made a change.

J.K. Rowling’s Harry Potter series taught me that there is no greater power in all the world than love. Masashi Kishimoto’s long-running anime Narutotaught me to never give up on my dreams. The Gate to Women’s Country, a novel by Sheri S. Tepper, taught me that going through a stupid phase doesn’t mark me for life.

The monomyth has roots in humanity’s psycho-emotional past. It connects us with ancient storytellers. And that’s not a bad thing. But there are other ways of knowing.

It’s time we looked to the future. You have a superpower that can change lives. Use it wisely, but use it.

It is time for us to imagine and write better tomorrows.

More Heroic Journey Resources

I am grateful to Shelley Sperry for her insightful comments and assistance in making this a better post.

Share this Article:

🟢 Twitter — 🔵 Facebook — 🔴 Pinterest

Sign up below and we'll immediately send you a coupon code to get any Story Grid title - print, ebook or audiobook - for free.

(Browse all the Story Grid titles)